I find the evolution of rock guitar tone to be a fascinating subject. A ‘59 Fender Bassman cranked up through its internal 4x10” speaker configuration sounds nothing like a Mesa Dual Rectifier through its oversized, closed-back 4x12” cabinet with Celestion Vintage 30s. And the speakers and speaker cabinet are a huge part of the equation—if you were to run the Mesa Recto into the Bassman speakers, you’d get a completely different tone, but one that leans in the classic Bassman direction.

The same thing goes for Vox tones—try running almost any amp into an open back 2x12” with Celestion Blues and you’ll instantly see just how much of that classic Vox character is actually coming from the cabinet.

It’s not always easy to do this kind of research. A lot of these differences become more apparent at volume, and cranking tube amps is just not an option for many guitarists. Assembling a large speaker cabinet collection is even more impractical. But because of these factors, guitarists have long been using speaker simulation devices to simulate the characteristic sound of different cabinets. Devices such as the Palmer PDI-09 apply a filter or EQ curve that mimics the sound of a guitar speaker to the full range output coming off your amp speaker out. This processed signal can then be sent to a PA or recording setup. Devices like this can work well, but you are usually stuck with one or two preset EQ curves, and the filter doesn’t replicate many of the complex factors that come into play when mic’ing a speaker—the thump of the cabinet, the airiness, or early reflections.

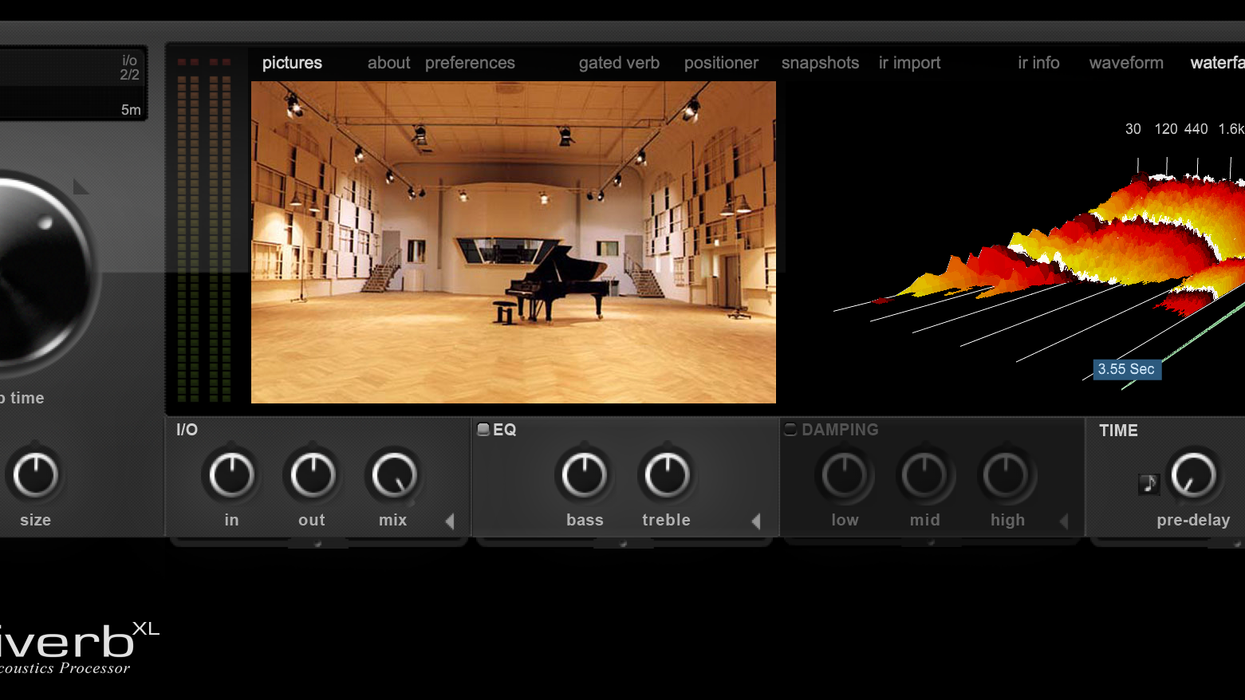

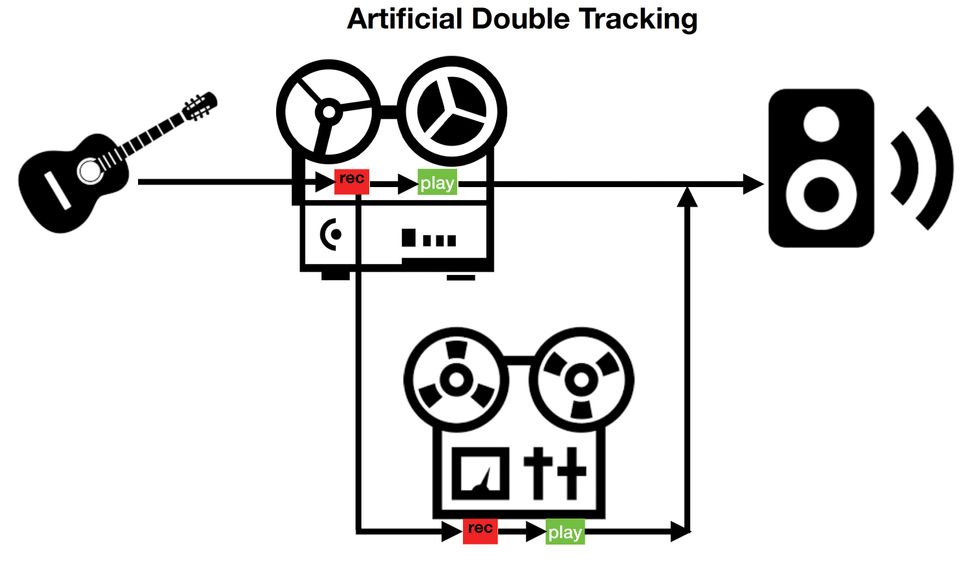

Recently, a whole new technology has surfaced called Impulse Responses (IRs). The first time I encountered Impulse Responses was in reading about Altiverb, the popular convolution reverb plug in. In lay terms, Altiverb gives you the power to sample any acoustic space you can think of, load it as an IR into the plug in, and voila, you have the characteristic reverb of say, the Sydney Opera House available to you in your DAW. But IRs are not just used for reverbs. You can effectively capture the sonic fingerprint of just about anything you can pass a sound through using IR technology—like a mic’d speaker cabinet.

Compared to traditional speaker simulators, I find that IRs offer much greater realism and depth. When you apply an IR to a line out signal from your amp, you are not just applying a preset EQ curve to your amp’s signal, you are essentially applying the distinct sonic characteristics of a certain speaker, cabinet, mic, mic preamp, and any early reflections that also make it into the mic during the recording process. There are libraries of IRs available to you at your fingertips, an almost endless variety of cabinet and mic’ing combinations. You can mix and match and blend virtual cabinets to your heart’s content. And when you land on a sound you really like, it’s easy to store that sound within your DAW, so you can call it up again later.

Of course, you can’t just plug a line out from your tube amp into your recording console or computer interface. Tube amps need to see a load (either a speaker or a dummy load of some sort). And you’ll need a good DAW and a convolution plug in that allows you to load IRs as well. To help us get a handle on what IRs mean for us guitarists, and how we can use them both live and in the studio, I’ve asked Mike Grabinski from Red Wirez Impulse Responses a number of questions.

Thanks for being a part of this, Mike! First off, what is an impulse Response, and how can guitarists incorporate them into their rigs?

Technically, an Impulse Response, or IR for short, refers to a system's output when presented with a very short input signal called an impulse. Basically, you can send any device or chain of devices a specially crafted audio signal and the system will spit out a digital picture of its linear characteristics. For speaker cabs, that means frequency and phase response, phase cancellation between multiple speakers, edge reflections, and other audible signatures wrapped up in the gnarly, old pieces of wood, paper, and glue that guitarists find so endearing. IRs will not capture non-linear stuff like distortion and compression.

When you're capturing an IR from a speaker cab, by necessity you are also sampling your D/A converter, power amp, the mic, mic preamp, your A/D converter, the cables you're using, and the room you are in. Basically, everything that comes in contact with the impulse as it makes it round-trip from your DAW and back again. So, it's important to use high quality gear and have a good recording environment. There's really no cheating physics.

Once you've captured a speaker cabinet IR, you process the signal coming from your amp by convolving it with the IR, imprinting the signal with the sound of your speaker cabinet. There are quite a few plug-ins and a few devices these days that will do the convolution part.

What are the benefits of using impulse Responses versus traditional mic’ing of speaker cabinets? IRs give you access to gear and acoustic spaces that might be too expensive or otherwise unattainable. The ability to run totally silent can be a real plus, too. Especially when cranking even a 30-watt amp can make your ears bleed, your dog run for the hills, or make your neighbors call the SWAT team.

IRs are a boon in a live situation, as well. Because you are essentially going straight from your rig into the house system, a setup using IRs is mostly immune to bleed and feedback from other instruments. You have more control over your tone. You are no longer at the mercy of the overworked sound guy, who would probably love to spend 10 minutes finding just the right mic position, but just doesn't have the time. And because you are eliminating a lot of the variables from the process, you can more easily reproduce your tone from venue to venue.

In your opinion, how close does an impulse response come to replicating the tone and overall coloration that that the typical cabinet/mic/mic preamp chain creates?

Early on I did double blind tests to convince myself it was worth the effort and expense to sample all these cabs. When levels are matched and you are comparing an IR and a mic in exactly the same position it is very hard to hear any difference at all. With dynamic mics, at least, I can sometimes pick out the IR, because a mic like the SM57 exhibits some distortion and I know what to listen for, and more importantly I actually know one of them is a real mic and one is an IR. With condenser mics, which are generally more linear, they sound pretty much identical. If you gave someone a recording and didn't tell them you were using IRs, they would never know, or even think to ask.

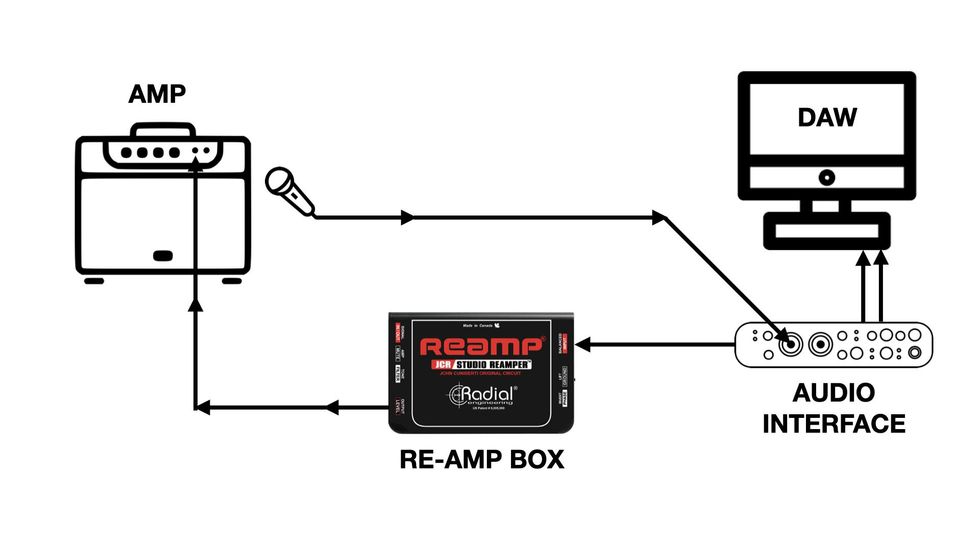

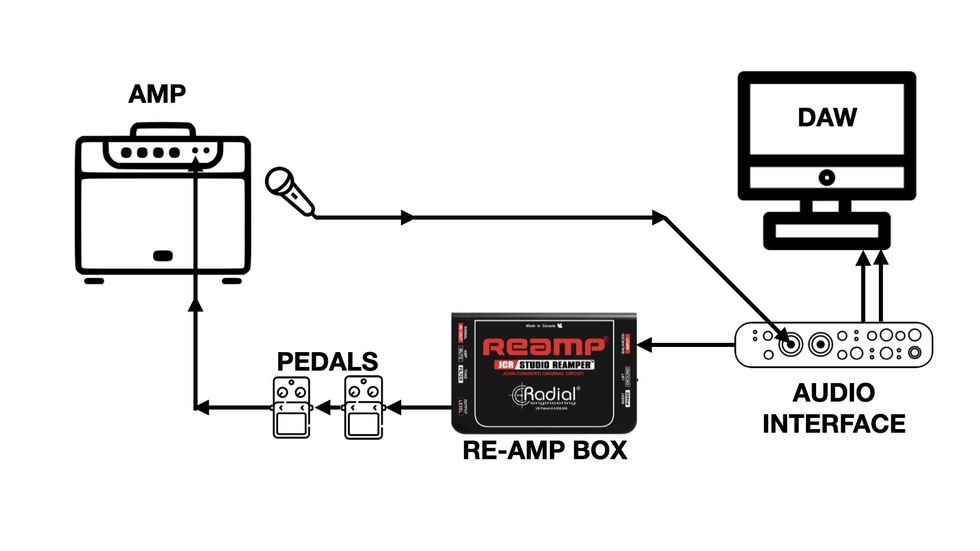

What's the best way to get your guitar amp signal into an Impulse Response that's loaded up in a typical computer host?Well, if making noise is an option, the best way, in my opinion, is to tap your amp's speaker out with a DI that can handle the power and then pass the signal through to a real speaker. That way, you are capturing preamp and power tube distortion and your amp still gets a reactive load. You don't really care what the speaker sounds like because you are going to be using IRs for the tone. You can shove it in a closet in the basement and as long as it can move some air, it's shouldn't negatively impact the DI signal. Some amps have the DI function built into the amp. Some even tap the signal coming from the power tubes, so a separate DI is not always necessary.

If you have to run silent, then you need a dummy load to take the place of the speaker, otherwise you can damage your amp's output transformer. There are lots of attenuators that also function as dummy loads out there. It is important to understand that your tube amp will probably react differently to a dummy load and you may find that your tone is missing the low-end bump and upper-mid rise you are accustomed to when using a speaker.

There can be several reasons for this, but one major factor is that speakers do not present a uniform load to your amp. If you look at a typical guitar speaker's impedance curve, which is a plot of the speaker's impedance across the frequency spectrum, you will see a big low-end bump and a steady upper-mid rise. This can also be described as a midrange scoop, depending on your perspective.

The load, or impedance, measured in ohms, will differ based on the frequency of the your amp's output. Solid-state amps have low output impedance, so their power output is not jerked around very much by the speaker's varying load. Tube amps have relatively high output impedance and as a result they deliver more power as the impedance of the speaker rises. And for a typical guitar speaker, that means you hear more bass and upper-mids.

Because a lot of dummy loads and attenuators present a uniform load to the amp, your amp's output will remain constant across the frequency spectrum. If you're accustomed to a low-end bump and upper-mid rise, you will probably hear this as the dreaded attenuator tone suck. To alleviate tone suck, you can use EQ. An alternative would be to use the sampled impedance curve of a real speaker to adjust the highs and lows in an authentic way.

What equipment does a musician need in order to use Impulse Responses with amplifiers, both live and in the recording studio?

You need a load for your amp, either a speaker or dummy load and a DI capable of tapping the speaker out of your amp. You also need a means to convolve the IR with your amps' output. In the studio, you can use a convolution plug-in. There are quite a few, including our own mixIR2 (wink, wink, nudge, nudge).

Live, the options are fewer and generally more expensive because you need a reliable device with enough horsepower to do the convolution with minimal latency. Not an easy task on a stage.

Let’s look at that for a minute. It's relatively easy to load an IR into a host on a computer in the studio, but what about boxes that allow you to do this easily live, in a road-worthy portable package? Say, with a built in load for your amp, and with multiple memory locations for IRs so you can load them up and take them to the gig? What's out there now, and do you see a market for more boxes like this down the road?

There aren't too many that I know of. There's the Fractal Audio Axe-Fx and Axe-Fx II, the Torpedo VB-101, and apparently you can load IRs into the Digitech GSP 1101 with some unofficial firmware mods. It is my understanding that the GSP 1101 truncates the IRs to 128 samples, which would limit your low and low-mid resolution. I suppose you could rig up a laptop, but I'm not sure how reliable and road-worthy that would be.

There seems to be increasing interest in these kinds of devices, so I'm sure more will pop up in the future.

Right. Also, we should mention, the Axe-FX and the GSP 1101 won’t provide a load for a tube amp but they do work great as hosts for IRs. I use the Axe FX this way live. Anything else you'd like to share?

San Dimas High School Football rules!

[Updated 12/12/21]