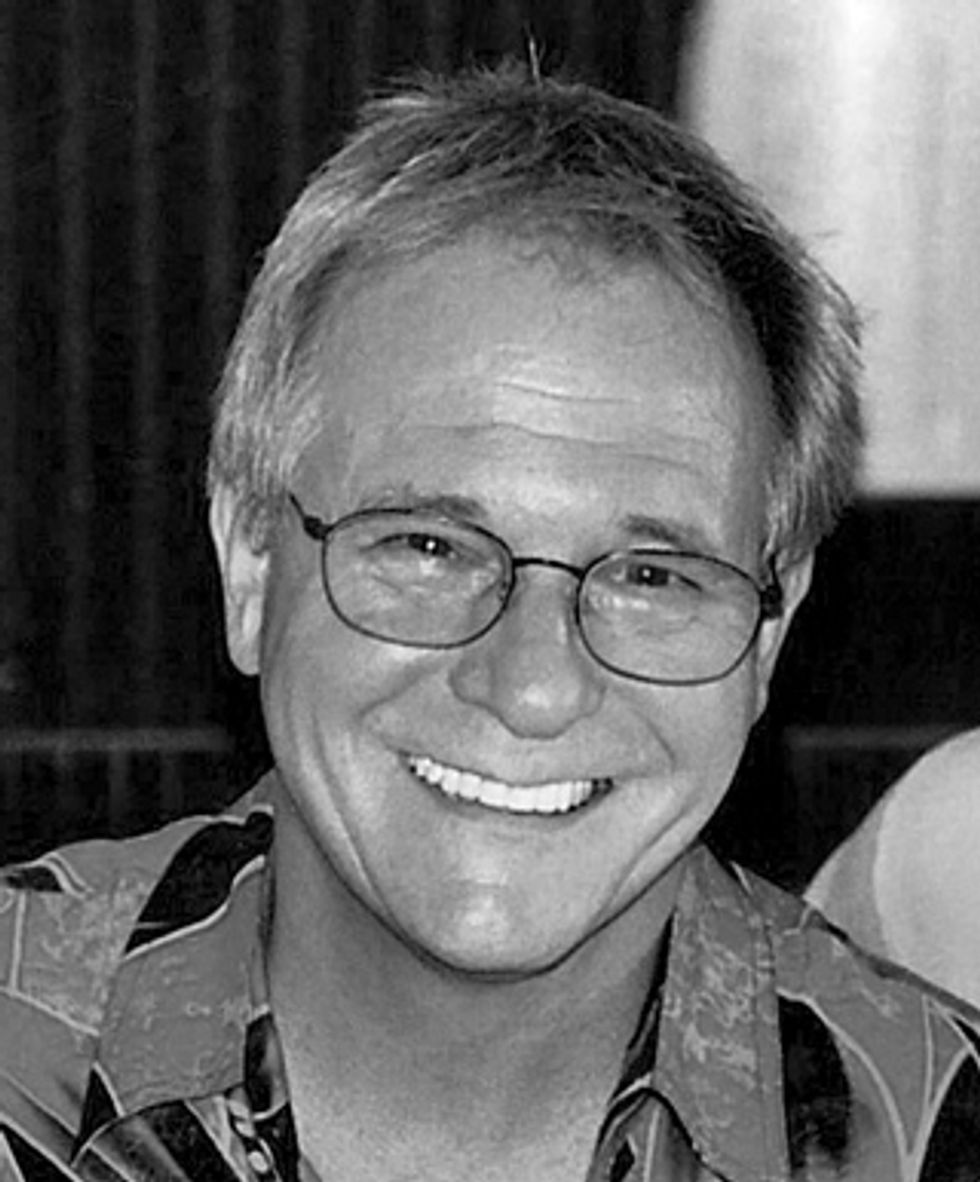

Recording at Paul Bonrud’s studio in Seattle. Photo courtesy Keith Olsen

With over 200 album-engineering and/or production credits to his name—and 39 of them have been certified gold, 24 went platinum, and 14 went multiplatinum—it’s no stretch to say Keith Olsen has helped define the sound of modern music. On top of that, he’s won six Grammy awards, sold more than 110 million records, become a trustee of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (the Grammy people), designed music gear, written books, and worked as a recording and touring musician.

Born in South Dakota and raised in the Minneapolis area, Olsen started his career as a musician but before long was hired as an independent staff producer for music-industry mogul Clive Davis (who, among others, was responsible for signing acts as huge as Janis Joplin, Bruce Springsteen, Aerosmith, Pink Floyd, and Earth, Wind & Fire). Olsen went on to become a major force in recorded music in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, recording with everyone from Fleetwood Mac to Foreigner, Whitesnake, Pat Benatar, Joe Walsh, Santana, the Grateful Dead, and Ozzy Osbourne. He also achieved incredible success in the film world, producing soundtracks for the hits Footloose, Top Gun, Flashdance, and Tron.

What’s your background as a musician—you’re primarily a

bassist, right?

I was actually a cellist. I was a bad acoustic guitar player, a bad

piano player, a bad bass player … anything I could get my hands

on that I could play and learn a little bit about. But I knew that I

liked music. I liked the theoretical aspects of it.

Did you have formal training?

Yes, kind of. I took private lessons from this guy who was just a

stunningly good concert pianist who taught me a lot about theory

and had me really going into the classics as a place to draw from.

Then I became a music-ed major at the University of Minnesota,

but I got drawn by the road—“C’mon, go out and play!”

While you were playing in folk bands, you rubbed elbows with

people who went on to big things—for example, sharing bills

with future members of the Mamas & the Papas and the Lovin’

Spoonful—and then you switched over to a rock band called the

Music Machine. How did you end up moving into the production

side of things?

While I was in the Music Machine, I kept finding these bands that

were opening for us. I found this band called Eternity’s Children

and we recorded their stuff. I was the producer and arranger and

engineer. We had a hit called “Mrs. Bluebird.”

How did you meet your future producing partner Curt

Boettcher and connect with Clive Davis?

I met Curt back at the University of Minnesota. He told me, “Hey

I got this deal with this guy and I can go into the studio anytime

I want.” My eyes lit up and I said, “Hey, why don’t we do stuff

together?” So we went in and worked on “Along Comes Mary” and

“Cherish” [with folk-rock band the Association], and we worked

with Tommy Roe on “Sweet Pea” and

“Hoorah for Hazel” [which became Top 40

hits in 1968].

Then Clive started hearing all this stuff by these two kids that were doing things differently, twisting knobs. A lot of record producers back then were “stopwatchers” and budget minders, period. Clive was interested in people who wanted to push the envelope. We met with him and he said, “I want you to be my independent staff producers,” because if we kept our independent status we could go to other studios. We weren’t tied into the CBS union contract that the studios had with the IBEW [International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers].

We did the Millennium album [1968’s Begin]—the first 16-track recording ever. We had to figure out how to lock two 8-track tape machines together to do it. It was kind of a turntable hit. Jerry Wexler from Atlantic gave me a shot at mixing a record with Aretha Franklin—her live album that was recorded out at a church in Watts. From there I got work with Mac Rebennack—Dr. John—and then started doing other things.

How did you find Lindsey Buckingham

and Stevie Nicks?

They were in a band and their booking agent

called all the A-list producers, and none of

them wanted to go to San Jose to see this

band named Fritz. He called the B-list producers.

He called the C-list guys. Then he

called the D-list guys, which was me and a

couple of other guys, and I said, “A free trip

to San Jose? Sure! I’ll go up and see them.”

I was picked up by Lindsey and their drummer in a van that had no seats in it. I sat in the back with the drum kit and the amps. When we got out of the van, he turned to me and said, “Well, help us set up!” [Laughs.] It was Lindsey and Stevie singing, and Lindsey was the bass player. The next weekend, I got them in the studio to cut a demo and I realized all the [other] members of the band were just average and Lindsey and Stevie were so special. So I said, “Let’s try to do a duo.” And they said, “No, no, no, we want to be a band, we want to be a band.”

Then Lindsey got mononucleosis and Fritz broke up because he was flat on his back for three or four months. So he started playing acoustic guitar, but he didn’t have enough energy to strum it. He could only lay his arm on it and do that flamenco kind of shot. Now think about the style that Lindsey plays—that’s how it happened.

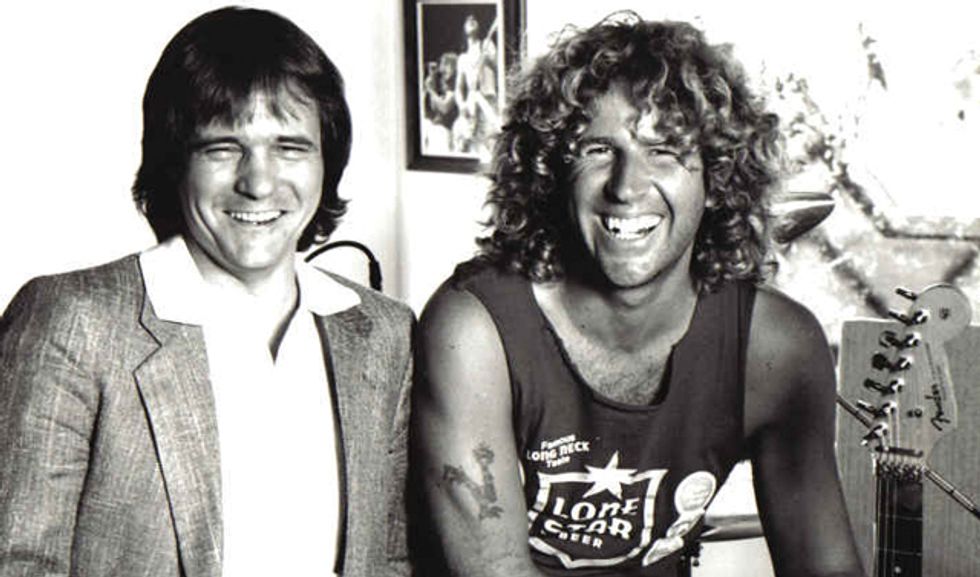

Keith Olsen with Ozzy Osbourne at Goodnight L.A. Studios in Los Angeles during the cutting of No Rest for the Wicked. Photo courtesy Keith Olsen

How did that lead to Lindsey joining

Fleetwood Mac?

I had signed on to co-produce with

Fleetwood Mac and engineer their album

after Bare Trees. How I made the deal to

do it was I played [Mick Fleetwood] three

tracks of the finished Buckingham-Nicks

record, one off an Emitt Rhodes record,

and one thing from Aretha Franklin. He

said, “Wow, this is really great.” So we

made a deal to do it. Then I got a call on

New Year’s Eve, and Mick says, “I’ve had

some bad news. Bob Welch just decided

to leave the band. So, that fellow in that

band you played me—would you see if

that guy would like to join my band?” And

I said, “Well, they’re going to come as a

set. Because they’re very much into their

own thing, and the only chance of getting

them to drop that would be to bring them

both on.” And he says, “Well, maybe that

will work. Can you see if you can convince

them to join my band?”

So I drop what I was going to do on that New Year’s Eve, take my date, and we drive over to Stevie and Lindsey’s house. I said, “Hey, Happy New Year” and all of this—I brought over the obligatory bottle of bad champagne—and I said, “Can we talk? Mick Fleetwood would like you to join Fleetwood Mac.” Immediately, Lindsey said, “Oh, no, no—I couldn’t possibly play anything as good as Peter Green did. How am I supposed to get up there and play ‘The Green Manalishi’?” Finally I get them, by the end of the night, to try it on a trial basis for eight weeks.

They started rehearsing with Mick and John and Christine [McVie], and they found they had a really neat sound together. Then when we got into the studio, it was totally unique. It was not like Bare Trees—it was not like anything else Fleetwood Mac had done. In fact, John came up to me and said, “Keith, you know, we used to be a blues band.” [I said,] “Yeah, I know, John. But it’s a lot shorter drive down to this bank.” [Laughs.] Because he knew we were commercial. But it was unique—it was the right thing—and halfway through that album, we knew. We knew.

Let’s talk about your approach to

recording guitar.

Get a great guitar player, get a great-sounding

amp, turn it up. [Laughs.] If

you’re recording electric guitar, find that

point on one of the speakers where you get

the highest frequency, and place the mic

there. [See the sidebar “Olsen’s ‘Shavering’

Cab-Mic’ing Technique” on p.148 for

more on this.] I was doing a seminar once

with guys from Shure, and I said, “Okay,

put the mic where you think it should

go on that 4x12 out there.” Then I had

the guy play guitar. I said, “Okay, play

a riff. You got the riff? Record it. Okay,

now, don’t change anything. Just unplug

your guitar from the amp.” I walked out

in the room with headphones on and just

moved the mic about an inch and a half

by listening to the hiss coming back as

the mic moved from the edge of the cone

[whistles an ascending pitch], right around

where the edge of the voice coil was. Then

I moved it around the voice coil and I

heard it change to the highest hiss. I just

put a little X on that speaker and I put the

’57 right there. Then I said, “Don’t change

any settings anywhere, inside or outside.

Now just plug in and play the same riff.”

He played the same riff and we went back

to back, A to B, and I’ve never seen so

many mouths drop open at the same time

like that.

Keith Olsen at Sammy Hagar’s house on the first day of rehearsal for Standing Hampton.

Photo courtesy Keith Olsen

Recording electric guitar is really easy, because you don’t want to use EQ if you don’t have to—you can just use the tone controls on the amp. Once you get the sound you want, just get it from the speaker into the console. The mic that I use all the time is the [Shure] SM57. You can’t really record a snare drum or an electric guitar without a ’57. You can use other mics along with it, mic’ing distant and this, that, and the other thing. But make sure you have one real close where the speaker is, where you’re right at the face of the piston instead of off that voice coil—because there you’re getting all that cone distortion, because the cone bends in different ways at different frequencies. Sometimes it’s pretty ugly distortion, sometimes it’s good distortion. It’s not even, so you want to be in a place where the distortion is all from the motor—a speaker is a motor, so you want to record it at the header instead of after the muffler. [Laughs.]

You mentioned using additional mics and

distant mics. Do you ever do that kind of

thing, or do you rely on just the SM57

up close?

Remember “Still of the Night” or “Here I

Go Again” [from Whitesnake’s self-titled

1987 album]? That guitar sound is two

mics: It’s a ’57 on one EVM 12L [speaker],

and then an AKG C 451 with a 10 dB pad

on it on the next one over—also an EVM

12L—in a 2x12 Marshall combo with an

open back.

If you want to get room ambience, then you put an AKG C 12 or a C 414 up at probably four or five feet off the ground, facing directly at the amp about six feet away—because remember, six feet away is about six milliseconds. As soon as you get past 10 feet away, then you start getting slap delay. You want ambience, not delay. The other thing I always do [for ambience] is decouple the speakers from the floor. I always get it off the floor and then tip it back a little bit so it’s aiming off to some wall. The angle of incidence—the angle of reflection—will send it around the room so you can start generating all of that room ambience. That’s how we did most of those parts.

Olsen's "Shavering" Cab-Mic'ing Technique

Keith Olsen has perfected a technique

for placing microphones on guitar cabinets

that he calls “shavering,” because

as he moves the mic into place, the

sound resembles what you hear from an

electric razor. Here’s how you shaver.

1. With your amp still on (and not on

standby), unplug the 1/4" instrument

cable from your guitar but not the amp.

2. Turn the amp’s gain and/or volume

up until there is audible hiss.

3. While wearing headphones to monitor

the sound from the microphone,

position the mic near the grille in front

of the approximate point at which the

edge of the speaker’s voice coil or

dust cover meets the speaker cone.

4. Move the microphone around the

edge of the dust cover, listening to

the change in the hiss as you do so.

5. Stop when you find the spot where

the hiss has the highest pitch or

brightest sound. Leave the mic pointing

at this spot.

6. Additional mics can be placed in the

room or on the speaker as desired

for enhancement, but this microphone

should provide the majority of

the tone.

Do you prefer doing that in a large room

or a small room?

At Goodnight L.A. [Olsen’s own studio], the

guitar room was probably 10 feet by 14 feet—

it was fairly dead. And when I say “fairly

dead,” I mean if I’d stuffed any more fiberglass

in there, it would have become an anechoic

chamber. [Laughs.] It was fairly dead. But

when I was doing leads and stuff like that, I

would bring the amps out of the guitar room

and put them in a fairly live, open room.

Any other thoughts on capturing great

electric tones?

Yeah. You can get a great guitar, a great

amp, great mics, a great speaker, and have

really cool stuff everywhere, but if the guitar

player isn’t happy, you’re not going to

get it. If the guitar player needs to hear it

screaming loud, put him out there in the

room and that’ll do it. A lead guitar player

has to have enough volume so that there is

that feedback to the strings. That only happens

at a certain volume level, so you just

gotta deal with it.

What about your approach to acoustic

guitar?

First, get a really good acoustic guitar.

Then, all I can say is you’ve got to use your

ears. It’s an acoustic instrument. You’ve got

to hear what the mic hears. The mic doesn’t

differentiate between wanted and unwanted

sounds. So you’ve got to really use your ears

and just mess with it.

I don’t particularly like putting mics up on the fretboard—I don’t think it’s necessary and it never really comes off. If it’s a really good-sounding guitar, the amount of squeaking and natural movement of the hand will be amplified all the way down the strings [to the mic near the soundhole and soundboard] and it will be part of the overall sound.

Occasionally, I record acoustic guitars in stereo, but then what do you do with it? As you’re starting things, you’ve got to look at the big picture. Because if you have a kit of drums, you’re going to have snare drum and kick drum in the middle. If you’ve got a lead singer, he’s going to be in the middle. Then there’s that guy who plays bass—he’s got to be in the middle. And then, if you’ve got an acoustic guitar player, well gee, you recorded him in stereo— it’s just going to sound like it’s in the middle. There’s all this stuff that ends up being in the middle. Certain things sound great in stereo, other things you don’t get as much phase shift and you get a better image in the end [with one mic] and just pan it.

Is there a particular mic you rely on

for that?

I’ve used Neumanns. I like using smallcapsule

condensers if the guitar has a lot

of boominess in it—you don’t want to use

a large- or a medium-sized capsule. There

is an Audio-Technica mic that is stunning

on acoustic guitars—the AT4033. It uses a

different alloy on the capsule—I think it’s

silver instead of gold. It’s really great. I just

found that by accident.

That’s not an expensive mic, either.

That’s not an expensive mic, no. I’m drawing

a blank on artists right now, but there

are a couple of singers that won’t sing a lead

vocal without that mic. It has that edge to it.

What’s your approach to recording

electric bass?

Get a really good transformer DI [direct box],

get a good-sounding amp, and this time don’t

“shaver” the mic—because you want to just

get the poof of air from the speaker. Just mix

that in and make sure you get it in phase.

What mic would you put on the bass

amp to do that?

I’ve used Electro-Voice RE20s, I’ve used

RCA [Type] 77-DXs, I’ve used a Royer ribbon,

and I’ve used a Neumann U 47 FET.

Because it’s such a small part of the sound

that gets to the mix, just about anything

works. You’re really just looking to move

air—you’re using maybe 25 percent of it and

75 or 85 percent of the DI [signal]. The only

other thing to do is to make sure that when

you want to compress, be sure you link the

compressors [on the DI and the mic] so that

when you compress the DI, you’re compressing

the same amount on the speakers and it

stays balanced and stays the same color.

Olsen's Go-To Mics

Throughout his career, Keith Olsen has relied on a wide range of microphones to capture

his world-class recordings. Here we list his favorites for a variety of applications.

Electric Guitar

To mic electric-guitar cabs, Olsen always uses a Shure SM57 up close. He’ll also use an

AKG C 451 condenser as a secondary close mic and/or a condenser such as an AKG C

414 as a more distant ambience mic.

Acoustic Guitar

Olsen considers an Audio-Technica AT4033 an invaluable acoustic mic, but he’ll also

sometimes use a small-diaphragm Neumann condenser.

Bass Guitar

To capture thumping bass tones that also breathe, Olsen prefers a direct box with a

Neve transformer in it for 75–80 percent of the signal. For the remaining 20–25 percent

of the signal, he usually uses an Electro-Voice RE20 dynamic, a Royer ribbon mic

(such as an R-121), an RCA Type 77-DX, or a Neumann U 47 FET as a secondary mic

to add some “air.”

Vocals

Olsen’s go-to mic for capturing some of the biggest, most recognizable voices in modern

music is an AKG C 414.

A lot of Premier Guitar readers record at

home. How much of a difference do you

think the gear really makes in the results

they can get?

Oh boy, that’s a loaded question. [Laughs.] If

you have a great song and a great performance

of that song, it doesn’t matter where it’s recorded

or how it’s recorded. You could record it in

your bathroom on a wire recorder that you got

from your grandfather—it’s still a great song.

Gear, equipment, it makes some difference.

Really high-end gear makes a difference. Is the

stuff that you can buy at Sweetwater or Guitar

Center good enough? Sure it is! You can get

that piece of software that PreSonus makes,

and their I/O box, and you can record really

great-sounding stuff. It’s really good. But,

you have to buy the gear, own the gear, learn

how to use the gear really well. And then you

have to learn how to play again—because you

haven’t been practicing because you’ve been

learning how to use all this gear!

How many bands are on MySpace and have a page on Facebook? You’ve got to do everything you can to get a leg up. One of the things that gives you a leg up is if you have a great song. And if you’re capable of a great performance, then don’t let technology get in the way: Pay a guy and go into a real studio where you can be an artist and you can work on getting a great performance of that great song instead of saying, “Huh, I wonder what this equalizer plug-in does?”

Yes, you can get good stuff at home. Most of the time, the issue at home is acoustics—what you’re hearing [in the room]—not the quality of the gear. The A-to-D [analog-to-digital] converters in that PreSonus box that sells for $299 are really good. Are they good enough? Well yeah, probably. But there again, what is more important, a great sound on the kick drum or a great song?