Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Create new drop-2 chord shapes from close-voiced triads.

• Learn how to use the hexatonic scale.

• Develop a more accurate right hand with string-skipping and hybrid-picking techniques.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

Eric Johnson has earned the title of one of the most respected guitarists on the planet with his countless hours of dedication. Johnson’s exacting demands can sometimes border on OCD—he claims to hear the difference between various battery brands used in his pedals and requires a specific number of string wraps on each tuner post. His inherent perfectionism set the preconceptions of guitar technique to an all-time high with two groundbreaking albums from 1986 and 1990—Tones and Ah Via Musicom, respectively. Both catapulted this Texan to the status of Grammy award-winning guitar god. Today, we’ll examine a few of the techniques that have taunted our ears, muddled our minds, and focused our phalanges for decades.

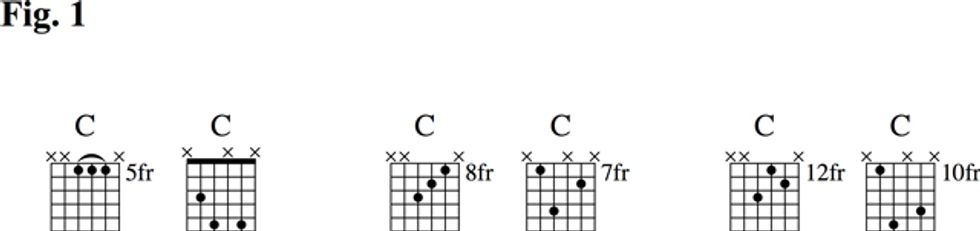

Along with his technical pentatonic flash and 500-pound, violin-like tone, Johnson’s quintessential contribution to modern guitar soloing is the use of string skipping to imply harmonic contours that are independent of his rhythm section. Johnson effectively does this via vertically stacked triads that span the fretboard, also known as drop-2 chords. A drop-2 chord is created by taking any close-voiced chord (where all three notes are within an octave) and lowering the second-highest note by an octave. In Fig. 1 you can see how this process works with three inversions on string set 5-4-2. Move these voicings to string sets 6-5-3, 4-3-1, and 5-3-1 for all major, minor, and diminished triads (if you’re bold), and then memorize the shapes of each to master them.

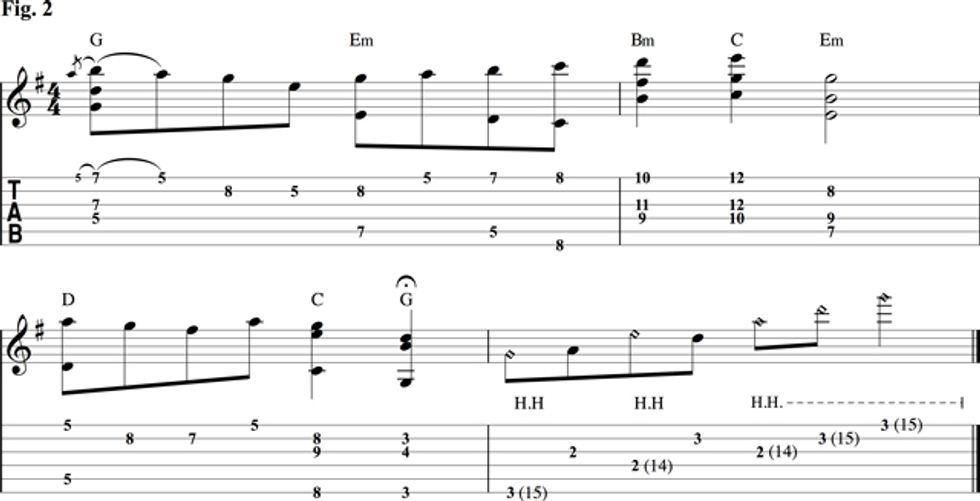

Now that you know how Johnson visualizes the fretboard, let’s take a look at how he applies this to some actual music. When his “Cliffs of Dover” became a widespread phenomenon, attracting musicians and listeners alike, he began extending the live intro by delaying the recorded intro’s identifying statement. He did this by using drop-2 chords to play chord melodies over a synthesized G pedal.

Fig. 2 is a free-time, voice-leading idea in the key of G, where the chord’s melody is the top note while the bottom notes move in intriguing counterpoint. The harmonics in measure four are played by fretting the G6/9 chord while picking the appropriate string with your thumb as your index finger gently touches the harmonic above the fret in parentheses.

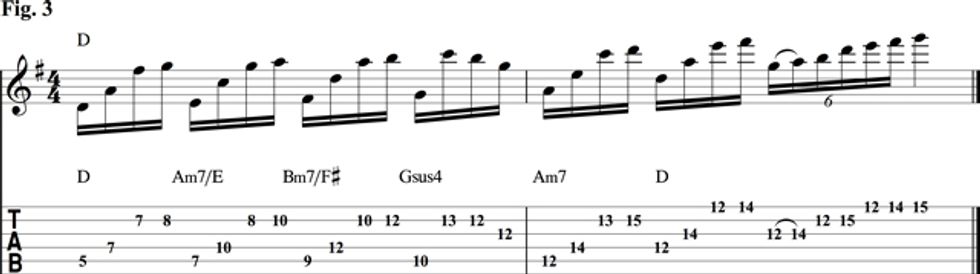

Fig. 3 arpeggiates drop-2 chords in a single-note soloing approach over a static D harmony (the triads used are shown between the staves). This is reminiscent of the first solo from Johnson’s “Desert Rose.” In order to fit the three-note shape in a 4/4 rhythm, we add an extra note on the final 16th-note of each beat. Notice that the “extra note” is a chord tone of the next triad (i.e., G is the b7 of Am7/E). That same harmonic sense from Fig. 2 is used as a consistent melodic device that creates contrast for the sextuplet G major phrase at the end.

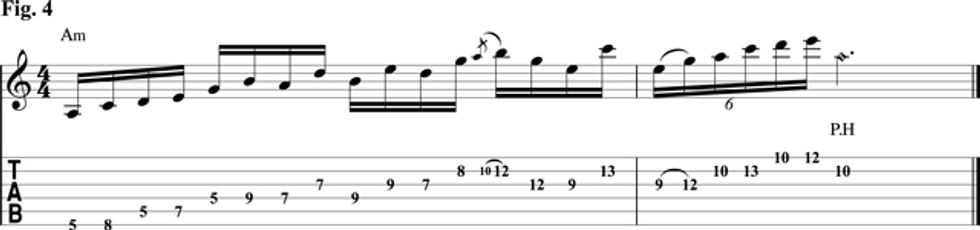

Johnson’s music-theory mastery comes forth in his use of pentatonic scales built from various notes of a given harmony—a thought process known as multiple pentatonics. This idea is simply to use different minor pentatonic scales too add color to a static progression.

For example, try using a minor pentatonic scale built on the 4th or 5th degree of the scale. In the key of A, we would have D minor pentatonic (D–F–G–A–C) or E minor pentatonic (E–G–A–B–D). Why? Well, each of these scales contain notes from the A Aeolian mode (A–B–C–D–E–F–G).

Fig. 4 succinctly displays this purpose through the ascending sequence’s lack of predictability, thanks to the E minor pentatonic that spans beats two through four. For the phrase’s terminal pinch harmonic, experiment with where you pick along the 2nd string to get a clear note—it’s a matter of where you pick, not how hard you pick.

A penchant for the unexpected has led EJ down paths toward surprising innovations, like the use of the minor hexatonic scale. This six-note scale adds the 2nd/9th to the otherwise utilitarian minor pentatonic scale.

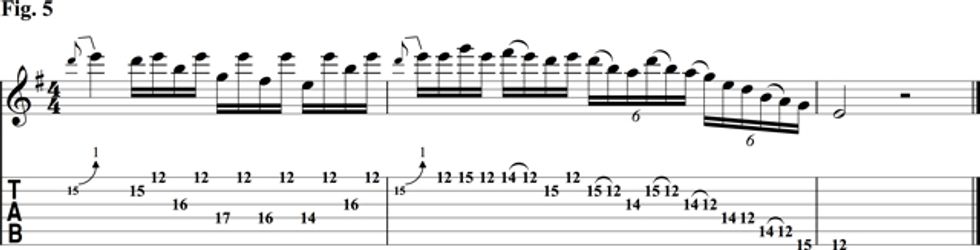

Fig. 5 sees it as the F# added to E minor pentatonic. The advantage of the hexatonic scale is twofold: First, it supports sequences that imply the use of the 9th and 11th. It also provides a nice passing tone between the b3 and root.

There is a bit of a technical curveball in measure one of this “Cliffs of Dover”-inspired line, where a repeated, root-note pedal tone (12th fret, 1st string) amidst a descending string-skipping arpeggio (Gmaj7, if you’re wondering) would cause nightmares for even the most efficient alternate picker. Use your middle finger to pluck the E notes and give your flatpick a rest. For the descending, sequential, sextuplet pull-off barrage in measure two, use light economy picking (successive downstrokes or upstrokes to cross neighboring strings). Be sure to keep the line’s flow by precisely slurring.

All musical ideas are related. You shouldn’t think that you’re learning new concepts in a vacuum. After you learn the A minor pentatonic scale shapes, you not only know how to play in the key of A minor, but you know the C major pentatonic scale and a Cadd9/13 arpeggio. Also, you’re only two notes away from the C Ionian, D Dorian, E Phrygian, F Lydian, G Mixolydian, A Aeolian, and B Locrian modes. (Those notes are F and B, by the way.)

Taking inventory of what you already know and building from there can be the most unexpected way of reinvigorating your musical creativity. Thinking about the guitar in new ways after the rules are learned is how we all progress. Enjoy the journey!