For Fender-philes that love vintage details, the first Vintera guitars, introduced in 2019, were welcome news. The Mexico-made series featured several custom colors rarely seen on the company’s more affordable instruments, the classic 7.25" fretboard radius returned, and the price was nice—most models were $899.

To players that cherished the Vintera guitars for their embrace of idiosyncratic and vintage-authentic elements, the expanded Vintera II series will probably seem like a Christmas stocking exploding from a Thanksgiving cornucopia into a Fourth of July fireworks finale. The burgeoning line now includes the Bass VI and competition stripe Mustang, a Telecaster Bass, and a Thinline Telecaster. It’s a beautiful batch of instruments that showcases some of the company’s most beloved and fascinating zigs and zags away from the norm, as well as several standard bearers.

While the three instruments that Fender sent our way don’t include the oddest of the series’ oddities, they still span the spectrum between the iconic, in the form of the ’60s Stratocaster, and more obscure instruments like the ’70s Jaguar with maple neck and black block fret markers. Two of our review guitars feature rosewood fretboards, which see a welcome return after the original Vintera series’ embrace of pau ferro fretboards. All three are built with alder bodies (only the Vintera II Telecaster Thinline is built with ash). Like just about any consumer goods, the new Vintera II guitars are affected by the realities of post-pandemic economics, and our review guitars range from $1,149 for the Stratocaster (which isn’t completely bonkers, given global inflation across the board) to $1,499 for the Jaguar, which is a bit more startling. Crossing the $1K threshold will be a tricky psychological hurdle for players accustomed to Mexico-made Fenders in the three-figure range. But as Paul Weller said, this is the modern world. And what’s reassuring is that the quality of these guitars is generally excellent, rivaling more expensive guitars in many respects.

Vintera II ’60s Stratocaster

A sunburst ’60s-style Stratocaster can elicit many different reactions: “Hello Old Faithful,” “You again?,” and “ahhhh...perfection” among them. Its form is familiar, beautiful, and balanced. In its Vintera II guise, the ’60s Stratocaster feels pretty great, too.

I once visited George Gruhn at the old Gruhn Guitars shop in Nashville and hung out a while in the little annex adjacent to the office where he kept his most primo stuff. Every A-list, vintage guitar model was there. But the one I can still feel in my hand to this day was a Lake Placid blue 1964 Stratocaster. The neck was perfect—a beautiful taper from a substantial oval at the 12th fret to a lovely, almost slim-and-narrow-feeling profile at the nut.

The Vintera II is heftier and blockier between the 5th fret and nut, and less contoured at the edges than many real ’60s Fender necks including that recalled 1964 Stratocaster. But they nail many other virtues—most notably the thickness from the 5th fret up. Like all the Vintera II guitars, and many others in the modern Fender line, the ’60s Stratocaster uses vintage tall fret wire rather than true vintage-spec frets. The difference doesn’t always feel huge, but it’s apparent. Hammer-ons and pull-offs feel a touch snappier and bending feels slick. If you have a heavy-handed approach to chording you might hear some notes go a little sharp. Players with a more nuanced touch shouldn’t have to worry much. Still, I wish Fender had gone the whole way to vintage spec and used shorter fret wire, which, in my book, feels great with a 7.25" radius. The rosewood fretboard, by the way, looks beautiful. Many of the pao ferro boards from the original Vintera could look chalky and arid, but the rosewood on the Vintera II looks deep and full of characterful grain.

Ring My Bell

Though there are many perfect amplifier companions for a vintage-style Stratocaster, I used a Tremolux piggyback and Fender Reverb tank with the reverb dwell laid on thick for much of this evaluation. The ’60s Stratocaster bridge pickup sparkles, splashes, and slashes in this very pre-CBS environment. It sounds sharp and focused, and pops with clear bell tones colored with a hint of trashy attitude. With a little less reverb, it dishes jangly Heartbreakers rhythm tones and punky Buddy Guy daggers. The out-of-phase fourth position conjures spanky Big Star-isms, and the middle position generates sweet circa-’72 Jerry Garcia dew drops and full-bodied rhythm. The neck pickup is primed for soul ballads, Gilmour space flight, and Kurt Cobain riffs. To state the obvious, these pickups cover a lot of ground. If you can level any complaint about them at all it’s that they lack some of the high-end detail of more expensive counterparts and sound a touch boxier as a result. Could you hear that in a band mix? Hard to say. I’d venture that many Stratocaster snobs would feel pretty good with taking this guitar on stage.

The Verdict

Full of punchy, spanky, slippery, and silvery tones, the ’60s Stratocaster feels like an old bud, a warm blanket, or an ages-old chisel. Like any Stratocaster, it has a very familiar, at times doctrinaire, personality. But that classic Straty-ness is sweet in the Vintera II edition.

While fit and finish were practically perfect on our test guitar, there was room for fine tuning. The G and B strings went flat more than I would like and the vibrato could be a little smoother and hold tune a bit better. I’d think these are problems easily fixed with a good setup—or even just a little care at home. That said, even in inflationary times it's nice to have those issues ironed out on a guitar north of $1K. When it’s all working though, the Vintera II ’60s Stratocaster feels alive and addictive.

Vintera II ’50s Jazzmaster

The Jazzmaster was born with about 18 months remaining in the 1950s. And while it’s easy to align the Telecaster and Stratocaster with other facets of ’50s culture and iconography, the Jazzmaster is, at least in my addled head, synonymous with the 1960s and beyond, making the notion of a representative ’50s Jazzmaster a curious one. But at least superficially, ’50s Jazzmasters were unique instruments marking a transitional time for Fender. Those in-between aesthetic elements make the ’50s Jazzmaster, which comes in desert sand and sonic blue, among the most distinctive looking guitars in the Vintera II line. Both colors are interesting choices for representing a ’50s Jazzmaster. Sonic blue is more associated with 1960s custom-color guitars, and desert sand, while a common ’50s Fender color, was generally seen on more inexpensive Duo Sonics and Musicmasters. Nevertheless, both hues look natural with the very-’50s gold-anodized pickguard. And on our desert sand review model, the rich slab-rosewood fretboard and gold pickguard help make the whole package look like a delicious chocolate-and-creme confection nestled in a gold foil wrapper. And I, for one, am all for guitar color schemes that evoke yummy food.

The Jazzmaster’s late-50s C neck is discernibly slimmer than the ’60s Stratocaster’s ’60s C shape—a potential surprise to those that associate ’50s Fenders with thick necks. Paradoxically, perhaps, the shape gives the ’50s Jazzmaster a more generic, contemporary feel than the ’60s Stratocaster. Yet it’s comfortable and feels fast, even if it leaves you longing for a little extra thickness from the 7th fret up. It’s hard to take issue with the Jazzmaster’s playability, though, which is lovely. I was certain that a Jazzmaster with a setup this low would fret out a bit, but two step bends from the 12th fret up went without a hitch. And in general the Jazzmaster feels a little faster under the fingers than the Stratocaster.

Of Zing and Springs

Like the Stratocaster’s pickups, the ’50s Jazzmaster’s pickups sound narrower and less lively in the high end than the pickups in more expensive American Vintage II counterparts (and, in this case, the 1964 Jazzmaster on hand for comparison). But the basic voice is still very recognizably a Jazzmaster, and without context—or in a mix—they would probably fool experienced listeners. The bridge pickup is sharp and zingy, the middle position atmospheric and warm. And the neck pickup is sweet and round. They are relatively free of noise, too—a distinction many Jazzmasters cannot claim.

If there is a single significant shortcoming in the ’50s Jazzmaster, it’s in the vibrato, which, in our review guitar, is prone to clacking sounds, particularly when you use a fast vibrato arm technique. This is a familiar issue in affordable, non-vintage Jazzmasters and Jaguars. (I run into Japan-made offsets from the ’90s with the same knocking problem.) Suggested and proven fixes for the issue range from loosening the vibrato tension screw to sticking tape between the bridge and vibrato plates. But given how much of the joy—and extended expressiveness— of playing a Jazzmaster is rooted in the beautifully bouncy and elastic vibrato, it would be nice to experience the best version of Jazzmaster vibrato right out of the gigbag.

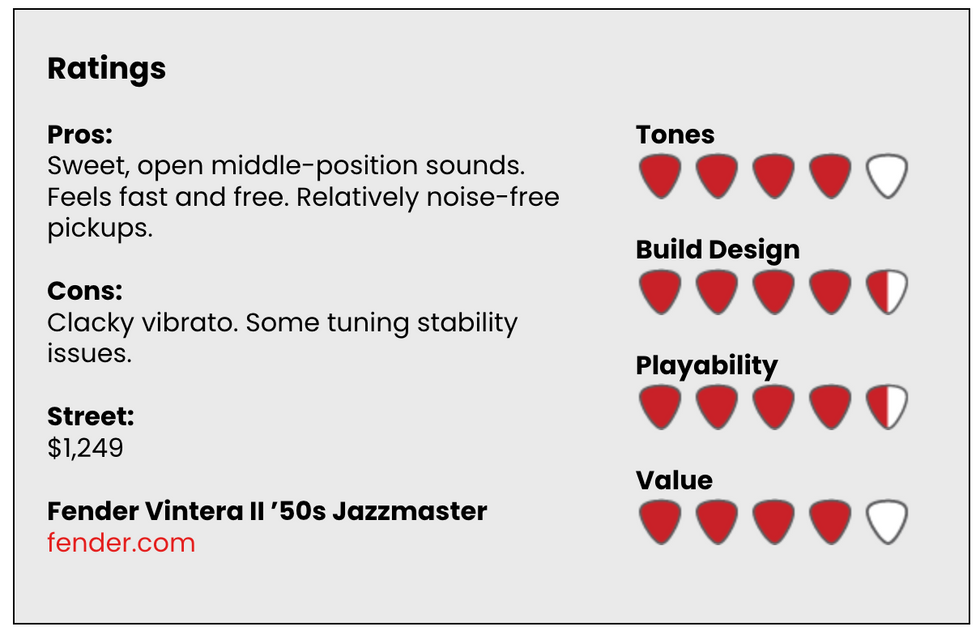

The Verdict

Clicking vibrato aside, the ’50s Jazzmaster is a very well made instrument that looks and feels more expensive. The guitar’s essential voice sounds authentic if a bit less widescreen than that of a vintage or American Vintage II specimen, and it feels fantastic in hand across the whole length of the fretboard.

Vintera II ’70s Jaguar

Charting guitar fashion via the British Invasion clock, you could make the case that Fender’s Jaguar started to fall out of vogue by the summer of 1965—Chris Dreja’s appearance with one on the cover of Having a Rave Up with the Yardbirds notwithstanding. But by the early ’70s, with Stratocasters topping the Fender hit parade, Telecasters adopting very Gibson-like humbuckers, and with Marquee Moon still a few years down the road, the jet-age Jaguar had most certainly ceased to look groovy to the natural finish and bell bottoms set. That didn’t keep Fender from taking a few final stabs at breathing life into its former flagship model—yielding the maple-neck-with-black-block look of the ’70s.

Though it has its fans, the maple-necked Jaguar is a peculiar marriage of design elements. To my eye, at least, the chrome on a Jaguar works best against a simple dot-inlay rosewood fretboard, which offers balance and dark counterpoint to the gleaming metal. Both of the colors that Fender offers in the Vintera II series make the maple neck work more effectively. Against the vanilla shade of the vintage white finish, the honey-tinted maple looks like pie crust against cream, and on our gloss black review model, the black block inlay is a stylish echo of the body’s finish. Fender picked well when selecting these color schemes.

Chokin' Up

I have friends that flat-out just don’t relate to Jaguars. That’s fine. I get it. If you’re used to a 25 1/2"scale, the Jag’s 24" scale can feel pokey, plinky, and petite. Even I sometimes find it tricky to switch between a Jazzmaster and a Jaguar mid-set for this reason. But the Jaguar is also a very funky guitar—not necessarily in the James Brown sense, but in the way the shorter, more compact-feeling neck (with an extra fret, compared to the Jazzmaster and Stratocaster) feels fluid, fast, and snappy once you get used to it. The focused, not-too-muscular fundamentals sound amazing for Malian guitar textures, splashy surf tones, Velvets garage haze, and concise, fuzzy psychedelic leads. I love all of those sounds and frequently use Jaguars to make them, so you can consider my opinion biased. But I think the Jaguar functions in a unique and compelling way in these environments, and others, that will appeal to players not weighted down by tone dogma. Our review Jaguar, by the way, is the slinkiest playing of the three guitars profiled here. The short scale feels incredibly fast. The neck also has the most comfortable profile of the three guitars—a thicker C that feels substantial and serves as a nice balance to the short scale. The vibrato is pronouncedly smoother than that on the Jazzmaster and less prone to clicking noises under all but the most fast and vigorous shaking.

The pickups, like the neck, will be polarizing. I heard everything I like about Jaguars here: focus, a less bossy, less-full-spectrum output that’s chimey, airy, rich with concise overtones, and not too fat for jangly arpeggios or fast, funk rhythms. Like all the Vintera II pickups, the Jaguar’s are a little less detailed and oxygenated than more expensive or vintage counterparts, but they have the accent down. I’ve played a lot of Jags over the years, and in terms of tone, this one was no less recognizable as a Jaguar, and just as fun in most respects.

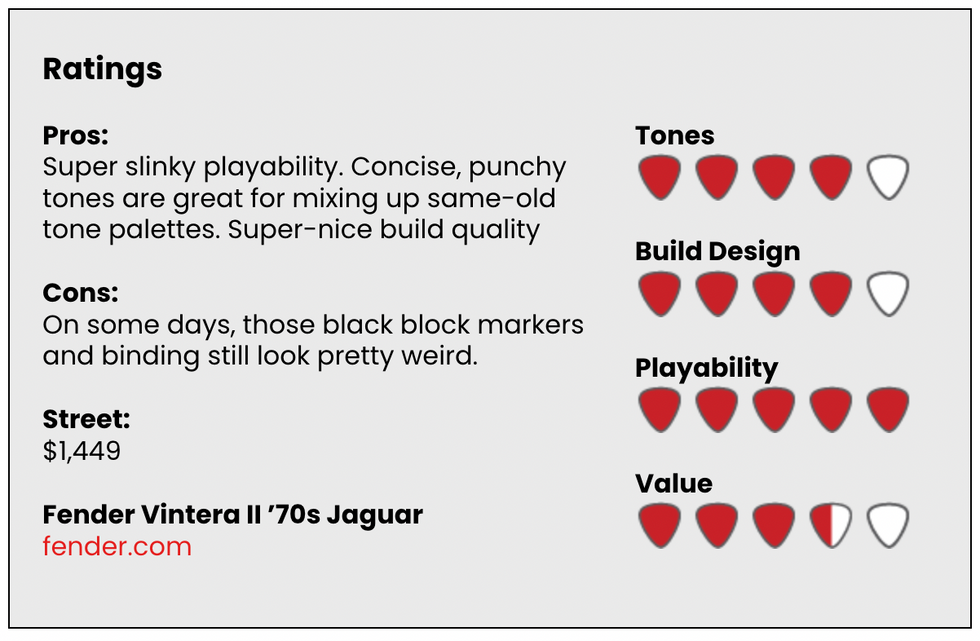

The Verdict

At $1,499, the Vintera II ’70s Jaguar is a full 200 bucks more than the Jazzmaster and 300 more than the Stratocaster. While the unusual black neck binding and block markers might account for some additional “exotic” manufacturing expense, it’s difficult to understand what accounts for the price, which starts to teeter uncomfortably away from the accessible category. Yet the Jaguar was the nicest playing and certainly the most unique feeling of the three Vintera II instruments reviewed here, and immensely inspiring for it.