It’s Bill Kelliher’s birthday. While many rock stars would celebrate the occasion with debauchery, the Mastodon guitarist spent a good part of his morning with Premier Guitar. Over coffee at the Club Room in New York’s Soho Grand Hotel, Kelliher told the tale of the band’s eighth full-length studio release, Emperor of Sand.

Okay, so rock stars only party at night? Well, maybe. Later that evening, we reconvened at a Mastodon listening event held at the Sonos New York City flagship store. Here—in an upscale environment where even the trash can was decked out in black velvet—Kelliher was joined by bassist/co-frontman Troy Sanders and rounded out his celebration by doing more publicity for the new album. These guys live Mastodon 24/7, and Emperor of Sand is a testament to their unwavering dedication.

Emperor of Sand was written during arguably the darkest time in the band’s personal lives. “When we were writing, there was a lot of illness and life-changing events happening all around us,” revealed Kelliher. “Basically, Troy’s wife fell ill with cancer last year and, hitting so close to home, we had to cancel a tour. Brann’s [that’s Brann Dailor, Mastodon’s drummer/vocalist] mom has been in and out of care. She’s been sick with some sort of crippling disease ever since I’ve known him. Myself … as soon as we got off the road two Septembers ago, I started sitting down to write the record and my mom fell ill. I found out that she had a brain tumor that was cancerous.”

Some might have been crushed, but Mastodon, which also includes guitarist Brent Hinds, persevered and ultimately turned these tragedies into songs. “Every day Brann and I would get together and have coffee and be like, ‘How’s your mom doing?’ We’re getting older and we’d talk about what happens when you get older,” says Kelliher. “I felt like it would do a disservice to our loved ones if we didn’t confront it and sing about it, or write about it, or talk about it, and use it for storylines in the making of the record. We were writing the record and it was rubbing off on our creative juices.”

Kelliher’s two-plus years of sobriety also made the writing process more fruitful. And after about a year of pre-production, the band recorded the album at the Quarry in Kennesaw, Georgia. Legendary producer Brendan O’Brien, who had worked with Mastodon previously on Crack the Skye, was brought back to lend his magic touch. And it worked: Emperor of Sand features the signature elements Mastodon fans have grown to love, from the haunting dissonances in “Andromeda” and “Sultan’s Curse”to the blazing, extended melodic outro solo of “Jaguar God.”

The presence of it is there.”

Almost two decades into their career, Mastodon continues to operate in perpetual overdrive. The band recently bought a building in Atlanta, Georgia, and opened Ember City, a rehearsal (and soon, recording) facility. Kelliher’s also got a new signature Friedman amp—the Butterslax—and a new ESP signature model, joining his LP-style ESP BK-600. In support of Emperor of Sand, Mastodon is set to embark on a North American spring tour with Eagles of Death Metal and Russian Circles.

But back at the Club Room, we started by talking about how bad times led to creating new music.

You’ve said that “Sultan’s Curse,” the first song on Emperor of Sand,is about being handed a death sentence. That song sets the theme for the album.

Kelliher: “Sultan’s Curse” was a song I had for probably six or seven years prior to it coming out on Emperor of Sand. I’ve got so many ideas, riffs, and parts of songs just floating around all over—in my Pro Tools, in my head. That particular song just didn’t make it on any other records. It wasn’t completely finished yet. That’s the thing with these songs: You know when they’re finished. When they’re done, it’s like, “Cool, let’s start writing the lyrics.”

I don’t write the lyrics. I’m just the riff guy. Usually when we write concept albums, it either has a very intricate story—something we made up—or a real-life event that influenced us and turned into a story. There are a lot of metaphors in there, which are open to interpretation, like all our lyrics are. But our fans are so die-hard and have such an emotional connection to our music that they are gonna understand it and feed off of it, and the message is really going to get through. My mom passed away, Brann’s mom is still doing all right, Troy’s wife is doing okay. I feel like the album is a real finished piece.

Can you talk us through the steps of a typical Mastodon demo?

I have a studio in my basement that I built last year. I built it as fast as I could because I had so many ideas and I needed a place to dump them out. It was just me and Brann. I did all the bass and all the guitars and everything. Because Brann and I had been working really hard at it, we knew the material inside and out. We played the songs for eight months before we really showed them to anybody else.

Did you factor in Brent’s parts as you wrote the riffs?

Over some parts, we’d say, “That’s where Brent will play a solo.” Or, like on “Steambreather,” it was, “We got the verse. Let’s put a little break in between the two verses where normally the chorus would go, but we’ll save the chorus for later and put a little guitar solo in there.”

When I’m down in my studio, I have the advantage of writing all the guitar parts and putting all the guitar harmonies over them. I don’t, by any means, write parts for him, but sometimes I’ll suggest things, like, “I did this cool harmony on the record and I want you to play this part.” Sometimes it works the other way. If he’s written something, it doesn’t always make sense for me because a lot of times he writes super complex, chicken pickin’ things, and I can’t even tell what the hell is going on.

Can you give us an example of something like that on Emperor of Sand?

“Jaguar God” is a Brent song, and in the middle it has that crazy scale thing. I sat there for hours and days, trying to slow it down and play along to it, and I could. But I didn’t feel comfortable playing it. If both of us are doing it live, it’s going to be insane. I don’t know if I could pull it off. I think I’d just get too much anxiety over trying to play it perfectly. And it kind of does the riff a disservice if you’re just playing the exact same thing when you have two different guitar players. Like I’m forcing myself to play like him and it’s not natural. I try to come up with stuff under what he’s playing to more lock up with the rhythm. I’m not really that dexterous.

You’ve got a new signature guitar.

The Sparrowhawk, with ESP. When I left Gibson, I was talking with ESP and everyone I knew kept saying what a great company they are, and how they make great guitars. I’ve always been a Gibson guy, though, so it was hard for me to jump ship, but it had to be done.

When I was first approached by ESP, the first thing out of my mouth was, “Can I design my own guitar?” I’m not a big fan of some of their shapes. It’s like, “That’s kind of too pointy, too metal. That one looks like a Les Paul, but it’s not.” I was a little put off. But they were like, “Of course, man. You can design your own guitar.” But I think they were kind of wary about it—like, “I don’t know how this is going to turn out.”

I took some ’Bird shapes, some RD shapes. I love Fender Mustang and Jag-Stang shapes, but they’re kind of small for me. I like them a little bit bigger. So I took all that stuff into consideration and sketched out this idea. We went back and forth a few times. There are a couple of different colors: a Pelham Blue, which is like a bright blue, and there’s a … I call it army green silverburst. But the custom ones will be available in whatever color you want. And it is one of the greatest playing and sounding guitars I’ve ever owned.

I still play my old Les Paul and my old Explorers, but there’s something about the way this Sparrowhawk just sits. I always wanted to be one of those guys that plays the guitar down here [motions a low-hanging strap], like Slash, but I learned that it’s harder to reach all those notes and not play too sloppily. Like Jimmy Page, who has got his guitars down by his feet. It looks cool as hell. And with the Sparrowhawk, it still looks like it’s sitting pretty low, but I can really get to all the stuff I need to get to on the fretboard.

What pickups do you have in the Sparrowhawk?

They’re pickups I designed with Lace. One set is called the Dissonant Aggressors, and another set is the Divinators, which are brand new, and which I kind of like better than the Dissonant Aggressors. The Dissonant Aggressors are definitely a metal-sounding pickup, but not so high output that you can’t get a good clean sound, too.

Tell us about your signature Friedman Butterslax amp.

I had been playing the Friedman HBE [the Brown Eye 100 set on its “Hairy” channel] and Jerry Cantrell JJ-100 heads, which sound incredible. But their clean channels weren’t what I was looking for, and I told them, “I want three channels and I want more gain.” They were like, “You’ve got plenty of gain.” I was like, “When I’m playing the HBE and JJ head, I’ve got them pegged to like 9 1/2 or 10. Why don’t you take what would be the gain at 9 1/2 or 10 and put that back to, like, noon?”

So, you’ve got half more gain to go?

Even if you don’t use it, it might be a selling point. It’s there if you want it, and I found myself using it.

So you actually go up to the new “10?”

To “11.” [Laughs.] I said to them, “Can you put an 11 on it?” That would be funny.

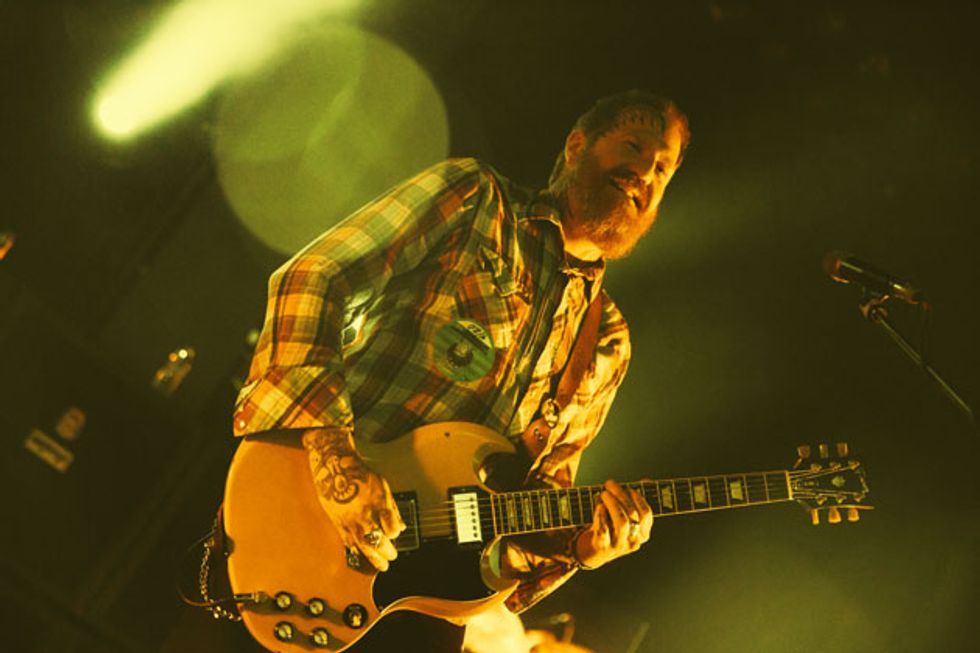

Brent Hinds, Kelliher’s 6-string teammate, provide much of the band’s flash, while Kelliher is the riff monger. At the April 22 Palladium show, Hinds dug into a Gibson SG, among other guitars. Photo by Debi Del Grande

How do you set your amp so you’ve got a massive amount of gain, yet have the clarity needed for those arpeggiated figures you play?

With the Friedman, you’ve got to be really articulate because it picks up every fuckin’ mistake. I’ve kind of got the perfect balance with the Friedman amps and with my pickups, where I don’t have to have too much gain. When I was a kid, I used to use a Chandler Tube Driver, one of the original ones—I still love that sound—and a Peavey Butcher head. I would crank it up, and I would only put the overdrive on a little bit, and I’d have so much feedback that I’d always be turning the gain down. I used to always scoop my mids, and then I learned that if you turn your mids up, you can actually hear your guitar. The presence of it is there.

Nowadays with my rig, I don’t have any feedback at all, which is awesome. With the Friedman heads, you just turn them on and they sound amazing already. I wanted a clean sound that was more reminiscent of what I grew up playing, like the Peavey Butcher head or Peavey VTM or Marshall JCM 800, which I graduated to when I could afford one in my 20s. It’s that sound of always having a distortion box, and when you turn it off, you’re on the gain stage but it’s at like 4 or 5. Kind of like an AC/DC sound. I call it clean, but they’re like, “That’s not clean at all.” It’s like a “Ride the Lightning” sound, when they’re playing the clean stuff. Like an electric guitar in a clean setting, but with a little bit of sustain.

Bill Kelliher’s Gear

Guitars

• ESP signature model Sparrowhawk with signature Lace Divinator pickups

• ESP signature BK-600 with signature Lace Dissonant Aggressor pickups

Amps

• Friedman signature Butterslax head

• Friedman 4x12 cabs with 65-watt Celestion G12M-65 Creambacks

• Fractal Audio Axe-Fx II

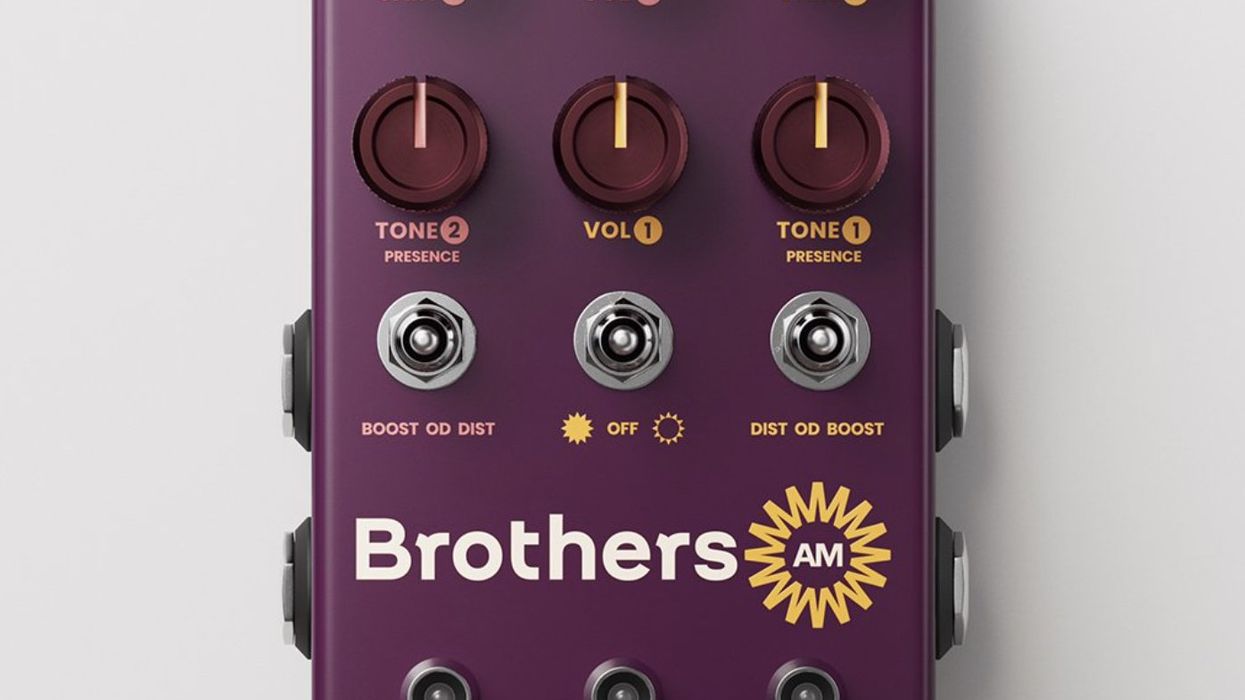

Effects

• Fractal MFC-101 MIDI foot controller

• DigiTech JamMan

Strings and Picks

• D’Addarios (.010–.052 for D-standard tuning; .010–.054 for C tuning; .010–.058 or .060 for A tuning)

• Dunlop Tortex Sharp .88 mm picks

So you’re not after a pristine clean?

I have to have a little bit of sustain and a little bit of grit. It’s got to be there. I had a really nice Orange, but when you clicked on the clean it was so fuckin’ glassy, like a country and western sounding, Beach Boys thing. It was really bright, and even with the volume turned all the way down it would cut right through my brain. That’s how the HBE clean was, and I was like, “No, no, no—it sounds like two totally different amps.” I want it to sound like the same amp, so you’re not getting this giant jump in sound that’s not real. I want it to sound natural.

Are you also using an Axe-Fx?

Yeah, I’m using the Axe-Fx in conjunction with my Butterslax. I can’t say enough good things about it. It took me a long time to jump ship to actually using it live, but I’m convinced now. There’s a big learning curve with that stuff, but I was like, “This is what I do for a living. I might as well start studying it and figuring out how to use it, because it’s so versatile.”

Since you mentioned the word “studying,” it’s interesting that you also give lessons while you’re on the road. What are the most common misconceptions people have about playing your guitar parts?

What I tell people is, “If it seems too hard to play, you’re probably playing it wrong.” Some guy was playing “Hearts Alive,” which has got a lot of chords—crazy chords, like really weird chords—that are plucked on each string. This kid was playing it real staccato, and going from here to here to here [moves fretting hand from a lower register to a higher one and back]. I was like, “No, dude. Everything is right here.” [Indicates that the riff is all played in one area of the fretboard.] You just keep your hand in the same place. If you watch most guitar players who are playing pretty complex stuff, nobody is playing like this [moves hand abruptly through different registers], unless you’re Michael Angelo. [Laughs.]

People probably also miss a lot of nuances when they try to cop your stuff.

Yeah. There are ghost notes. A lot of people don’t pick that up when they’re learning our stuff. See, I never took any lessons, but nowadays I can just watch a video. There are probably kids out there who have only been playing for a year that can shred the hell out of the guitar. I’m more focused on writing stuff that’s a little different. There’s only so much you can do. That’s why we use different tunings, and I’m always putting my fingers in a weird configuration to make up new chords.

Your use of dissonance sounds very organic. Is it based on theory or intuition?

It’s more intuition. Does this feel natural, like it should go to this note? But you know, I’m always experimenting with dissonant notes. I love the sound of two notes a half-step away that are trying to find each other—that kind of wobble. On nearly every single riff I write, at least in the past couple of years, I almost always throw those notes in there. Like when you have an open string, you can tell the difference on a record between an open string and a fretted note. I try to stay away from playing a fingered note that could be an open string.

Is it hard to physically control the open strings from ringing out too much or getting noisy?

I’ve got all kinds of tricks to muting them. With this hand, too [lifts left hand], sometimes I can intuitively mute. Like my fingers know how to cut it off when it needs to be cut off. There are songs like “Scorpion Breath,” on the new album, where I hit the high string and I have to arc my hand so I can keep playing the low notes under it. I’ll have the B string still ringing while I play the low notes, and I let it ring as long as possible until the next time I hit it.

In that specific case, what do you do about the G and E strings, which are also potentially ringing because your left hand isn’t muting them?

You have to hit that B string precisely. When I was doing it for the record, I hit it every time without having to dub in just that note. Every time, I played it exactly the way I heard it. That song, the B string is tuned to A, and you’re hitting the octave of the low A. So when you hit the low string, it always bounces a little bit, because I don’t use super heavy-gauge strings, usually .010–.052s or .054s. I never have any problems with fretting out or tuning, and I hit pretty hard.

It’s not surprising that you hit that B string right on every time. You’re known for being really obsessive about playing everything precisely.

Oh yeah. I’m always trying to become a better guitar player and the first rule is to not be sloppy. [Laughs.]

Do you and Brent discuss the actual fine details of your parts down to, say, slides and hammer-ons and pull-offs, to guarantee complete synchronicity?

It depends on if you’re asking me to learn his part or him to learn my part. [Laughs.] When I learn his part, I sit there and take notes, and take videos. Normally we don’t play the exact same thing, but when he writes something, I try to mimic it as closely as possible.

Does he take the same approach with your parts?

[Laughs.] He kind of just does what he does. I try to tell him sometimes, “That part is not right,” or whatever, but sometimes I’m like, “That’s just the way he is.”

Does that drive you crazy?

[Laughs.] Yes, it does drive me crazy. I love the guy and he’s an awesome guitar player, but sometimes I have to change to what he’s doing, even if I wrote the part. It’s like, “Whatever, I’ll just change that note.” You make it work somehow.

YouTube It

Mastodon rips through “Show Yourself,” the first single from the band’s new Emperor of Sand, on Jimmy Kimmel Live! On stage left, note Bill Kelliher and his brand-new signature axe, the ESP Sparrowhawk.