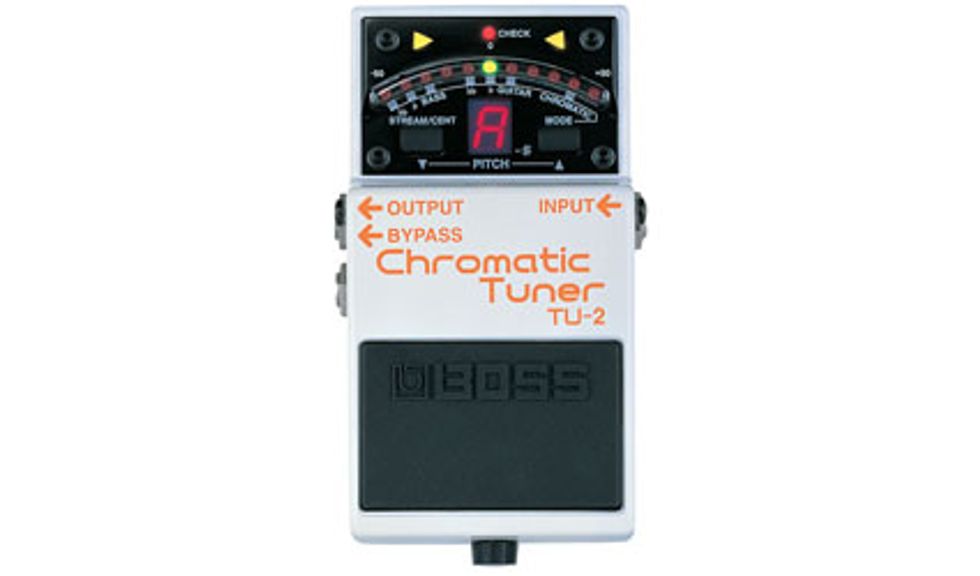

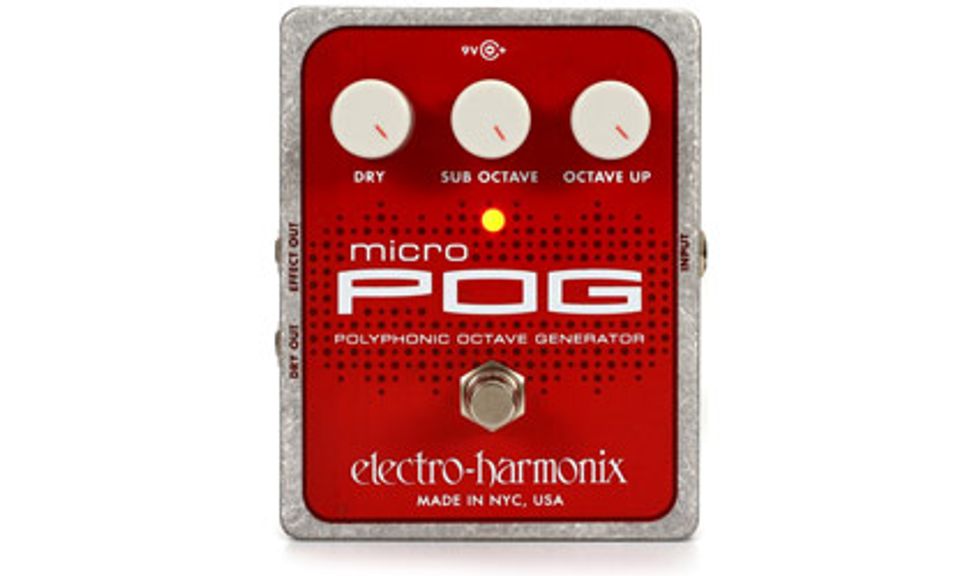

His pedals out front onstage include a Boss RT-20 Rotary Ensemble, a Boss CH-1 Super Chorus, TC Electronic Flashback Delay, Electro-Harmonix Micro POG, Pedalworx Doobie Double Drive. Simmons has one tuner for electric and another for acoustic: a Boss TU-2 Chromatic Tuner and a Peterson StroboFlip. Everything is powered by a single Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 Plus.

Special thanks to tech Chris Ledbetter.

Click to subscribe to our weekly Rig Rundown podcast:

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)