Anthony Joseph “Joe” Perry, a true American rock guitar hero, has held down the lead guitar chair for nearly 35 years with Aerosmith, often touted as America’s premier rock band. Born and raised in the suburbs of Boston, MA, Perry, of Portuguese and Italian descent, was taken with the sounds of the ‘60s British Invasion bands, and counted Jeff Beck, Jimi Hendrix, and particularly Fleetwood Mac’s Peter Green as inspirations.

Formed in 1970 in Boston, Aerosmith paid their early dues, played hard and partied harder, and enjoyed hits like “Walk This Way” and “Dream On.” In the summer of 1979, Perry, at odds with other members of the band, and dealing with the strain of increasing drug dependency, left Aerosmith to start The Joe Perry Project, a group with a rotating lineup that recorded three albums and toured almost constantly. With his personal and professional life a shambles, Perry and his friends in Aerosmith patched things up in 1984, got into rehab, cleaned up, and enjoyed 25 years of unprecedented success with a series of hit singles, MTV videos, critically-acclaimed albums and sold-out tours. Aerosmith have sold an astounding 150 million albums worldwide, and are members of The Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame.

But flash forward to Autumn 2009, and Aerosmith was once again in a state of confusion and turmoil. Lead singer Steven Tyler, eager to establish himself as a solo artist at age 61, decided to take an indefinite hiatus after falling off a stage this past summer. While rumors of the band’s demise abounded, Perry went on record saying that Aerosmith was still together, and might look for a replacement for Tyler. In the meantime, Perry, never one to sit still, and with a backlog of new material, quickly recorded and released an album in October called Have Guitar, Will Travel, featuring a newly handpicked group of musicians. Billed again as The Joe Perry Project, the band has just completed a short US tour, and is poised to take their act overseas within weeks of this writing, opening for Mötley Crüe and Bad Company.

A self-confessed ‘60s rock fan, guitar collector, horse enthusiast and gearhead, Joe spent time discussing his love of funky Supro guitars, and how he surprisingly plans to unload a significant portion of his vast collection in the coming year.

What was the spark that ignited your desire to play guitar?

It was a series of things, really. I had an uncle who owned a homemade four-string instrument that looked like a ukulele. He would probably get mad if I called it a ukulele, but that’s what it looked like. During the holidays, he would play Portuguese folk songs and then let me play with it. I must have been five or six at the time. I used to go to school and listen to the orchestra, and I didn’t like any of the wind instruments, but I did like the guitar. I begged my parents for an acoustic guitar, which they bought for me. It came with a 45-rpm record that taught you how to tune, how to strum, and all that. This must have been around 1961 or 1962—definitely before The Beatles came out. I bought a fake book and learned chords from that. I never took lessons.

Once I discovered The Beatles, their music and movies, and all the other British bands like The Stones and Yardbirds, I was captured by rock ‘n’ roll.

You were influenced by Jeff Beck and Jimi Hendrix specifically, but how did Peter Green fit into the equation?

A lot of English bands came to Boston before they hit New York back then. I guess they wanted to warm up first there. I had a friend who got a lot of free tickets to the Boston Tea Party club. Fleetwood Mac took up residence at the Tea Party for weeks on end, and I must have seen them thirty times or more. I saw them on great nights, terrible nights, nights when they were all drunk. Peter Green’s style, attitude and sound really got to me. These guys didn’t care about being rock stars. It was all about the music for them. I became a big fan of Fleetwood Mac. I guess you could say I was most influenced by the second wave of British bands, like The Yardbirds, Mac and The Who.

Did you ever see The Yardbirds live?

No, they had broken up by the time I started going to concerts. I wish I had seen them.

The first time I saw Aerosmith, you guys were opening for Mott The Hoople.

We toured with them a lot in the beginning. I can’t say enough nice things about those guys. They were very good to us. They took us under their wing, you might say. All they wanted to do was play rock ‘n’ roll and party. They’re back together with all the original members playing shows in England, and I heard they sound great.

Let’s talk specifically about guitars. What are you using on tour right now?

I’m using a few Strats right now, including the first upside-down one I had back in the early days of The Project. I got that one out a while and ago and began playing it again. A left-handed Strat played righty just has a whole different vibe and sound that a standard right-handed one doesn’t have. I have a black Jeff Beck Strat, not a normal color for that guitar. I have both of my signature Gibson Les Pauls, my Billie guitar, a reissue Gibson Custom Shop flametop, a Gretsch White Falcon, a Dan Armstrong see-through Plexi guitar for slide, and a Supro Ozark that’s strictly used for slide. I rotate guitars a lot out of the collection. I really don’t like changing guitars that much onstage, but I have so many great ones that I like to play. I went through a ton of Strats over the years trying to find the best ones—the same with Les Pauls. You want to play good guitars all night. I also have a guitar that was put together for me by RS Guitarworks that has a Fralin P-90 in the bridge and Joe Barden pickups in the middle and neck.

Is that the brown guitar with the studs on the body?

Yes, that’s the one. I call it the Bones and Bullets guitar. There are pictures of it in the booklet of the new CD.

Performing at the Filmore at Irving Plaza, NYC, Nov. 10, 2009. Photo by Frank White

What makes a great guitar to you?

It’s the little things—the nut, the bridge, the setup. You know how it is: every guitar is different and some are just special. My Billie guitar rings like a bell when the volume is down. When you turn it up, you can get a great rock ‘n’ roll crunch, and it’s a good heavy metal guitar too. It does everything well. That guitar is really special.

How did the Billie guitar come about? I know several guitarists who speak fondly of it, for obvious reasons.

It started out as a standard B.B. King Lucille model, and I picked it because there were no F holes to get in the way of the artwork. It’s amazing that guitar plays as well as it does. I changed the electronics; it has one volume and one tone now. The inspiration was the nose art you saw on airplanes during World War II. I wanted to put the most beautiful woman I could find on there, so naturally, I chose my wife. I sent it out to an airbrush artist and he did a great job. When I got it back, I opened the case and gave it to Billie, and she hated it. She was so embarrassed she refused to come out of the dressing room at Aerosmith shows when I was using it. She couldn’t stand the sight of seeing herself on a 30- or 40-foot screen at shows. Now, she’s okay with it.

I read that you have about 600 guitars. What are some of the standout pieces from that collection? Which are your favorites and why?

It’s really closer to 500 guitars, and there are so many great ones. To tell you the truth, I want to unload a large portion of the collection. I’ve been working with Perry Margouleff [Author’s Note: Margouleff is a noted record producer and vintage guitar expert] on the best ways to disperse them. I want to sell a lot of them because they’re sitting in storage, I just don’t have time to play them all, and I’d rather get them into the hands of guitarists who will play and enjoy them. Some may go on consignment, others we’ll sell directly to collectors. Others we may donate to charities or give to kids.

Joe, do you have a Supro Dual-Tone you want to sell? That’s a guitar I’ve always wanted. Let’s talk about it when you get ready to sell, okay?

Yeah, I have two of them. Sure, no problem. We can do that.

You have two signature Les Paul models. How much input did you have in their design?

They let me decorate them; it was mostly about cosmetics. They’re pretty much standard Les Pauls. The first one has the black see-through finish. I wanted the flame top with that nice ripple effect you get. When light catches it, the flames come through. I had Gibson make them lightweight, and it has a Tonex pot on the neck pickup, which gives you a static wah sound. That’s a very cool effect for solos. The Boneyard model is custom shop Gibson. My wife is an artist who’s had experience working in multimedia visual arts, and she had an idea for the finish to bring out the tiger stripe effect. We were at the Gibson custom shop and she explained the idea to the guys there. Their response was, “That won’t work.” They tried to talk her out of it. She said, “Can’t you just try it this way?” They did, and it worked. It really brought out the wood grain. The top is sort of a greenish-orange shade, and the flame top is very prominent.

I also saw a recent promo photo of you playing a black Gretsch. How do you use it?

That guitar is a real squealer. It’s a Black Falcon. It feeds back too much live. I used a White Falcon on that cut from the new album, “Somebody’s Gonna’ Get Their Head Kicked In Tonight.” Gretsches are good rockabilly guitars. Fred Gretsch gave me the White Falcon I have.

I read somewhere that you have a lot of cheap, funky electrics like Teiscos, Supros and Danelectros. Is that true?

Yeah, those cheap guitars are so much fun to play and collect. I love the Supro Ozark model. I have two of them. I think the Ozark is the best slide guitar ever made. It’s got a flat fretboard, like the Dan Armstrong see-through, and I think that factor makes them both great slide guitars. I have written songs especially for the Ozark. The pickups on the Ozarks go over and under the strings, and the sustain is amazing. The old Rickenbacker horseshoe pickups were similar but not quite the same. There are so many variations to those old Supro guitars. No two are ever alike.

I have a red Supro Belmont I bought from a kid this past summer for $250. I had it rewired and set up for slide by David Petillo. It’s a killer. Those old Belmonts are cool too. Supros are just the best slide guitars.

What's your onstange amp rig right now?

I’ve always liked something that’s crunchy and something that’s clean, so it’s usually a combination of Marshall and Fender. I use a ’64 50-watt Plexi with an 8x10 Marshall cabinet, a ’69 Marshall Super Bass Plexi head, plus a couple of Dual Showman amps with two 15s. I also have a ’50 Bandmaster Tweed with original Jensens that smooths out and melds the sounds together. There are other amps we use onstage too. In the studio, I’ll use a Fender Champ or an old Epiphone amp with an 8" speaker.

What’s on your pedalboard right now?

I’ve got a Fulltone Echoplex reissue, a Fulltone Ultimate Octave, an Electro- Harmonix Holy Grail Reverb, a blue Line 6 Modeler, a green Line 6 Delay, an Ernie Ball volume pedal, a DigiTech Whammy pedal, an original Klon Centaur, a Jimi Hendrix Signature Cry Baby wah and other stuff. The pedalboard is pretty extensive. One of the coolest things I have on there is an actual siren built into a pedal.

Premier Guitar’s motto is “the relentless pursuit of tone.” How would you define good tone?

Good tone is what works for the song. Your tone forms the basis of each song. Basically, there is no bad tone, just bad uses of tone. What’s good for one song can be bad for others. I use lots of different tones depending on the material.

The tracks I’ve heard from your latest CD have a very raw, dense quality, as if the band recorded together in the same room, the way it was done in the late sixties. Was that the vibe you were going for this time? You recorded this disc in your home studio, right?

That’s exactly what we were going for. We isolated the guitars just enough and everybody played at the same time going for keepers. With this record, we went for good takes every time. If someone screwed up, we did another take or pieced things together. The whole vibe was about getting good takes. The musicians I have now allowed me to operate that way, and it worked out real well. Aerosmith recorded Honkin’ On Bobo in my studio the same way. I’ve always had a home studio. In the beginning, it was just basic four-track stuff, but now, I have a great studio at my disposal all the time.

I frequently hear older musicians complain that there are no young guitar heroes. Are there any young guitarists you like?

I really like Jack White. He plays stuff that sounds like an exercise, but you can tell he’s listened to blues guys like John Lee Hooker. I hear the same thing when I listen to things my sons play—simple riffs, but you know they can develop what they’re doing if they work on it. Jack White will have longetivity. There are a lot of good young technical players out there.

Do you have any final words of wisdom and advice for guitarists?

Practice with a metronome. They’re cheap, you can buy one that attaches to your guitar strap, and they’re great for developing your time and feel. Every guitarist, every musician, should work with a metronome or a click track to develop a good sense of time.

Joe Perry’s Gear for the Joe Perry Project Tour 2009/2010

Left to right: Joe Perry Boneyard Gibson Les Paul, Gibson Custom Shop Les Paul Joe Perry Model (stock), 2000 Dan Armstrong Plexi, "Billie Perry" custom ES-335 Lucille, Mid-'50s Supro Ozark

Left to right: Joe Perry Boneyard Gibson Les Paul, Gibson Custom Shop Les Paul Joe Perry Model (stock), 2000 Dan Armstrong Plexi, "Billie Perry" custom ES-335 Lucille, Mid-'50s Supro Ozark

Guitars:

“Billie Perry” custom Gibson ES-335 Lucille: a one-of-a-kind guitar with his wife Billie’s picture on it, and one of Joe’s all time favorite guitars. Boneyard Green tiger Gibson Les Paul with a bigsby tailpiece, stock: the prototype Boneyard Les Paul; it says “prototype” on the back of the headstock.

“Bullets and Bones” guitar: custom-made for Joe by R.S. Guitarworks; features a Lindy Fralin P-90 pickup in the bridge, Joe Barden pickups in the middle and neck, and a Trem King tremolo.

2000 Dan Armstrong Plexi: nothing says open-tuning slide guitar like this Plexi.

Mid-‘50s Supro Ozark: used for slide work only.

Black Gibson Les Paul: Custom Shop Joe Perry model, stock.

Gretsch White Falcon: given to Joe by Fred Gretsch Jr.

Ernie Ball Silhouette Guitar: mid-‘90s alloriginal with a Trem King tremolo.

Mid-‘70s Left-Handed Strat with reverse Telecaster headstock: the actual guitar from the first Joe Perry Project tour, and one of the guitars Joe has owned the longest. It has Barcus Berry pickups in it.

Left-Handed Fender Jim Servis/Joe Perry strat: loving referred to as “Frankenstrat,” and built by Joe and Jim Servis. It’s basically a parts guitar that has literally been in a fire; a left-handed Fender body and a reverse Tele Warmoth neck, Barden pickups custom-wound for hotter output, and a really cool green pickguard.

1992 Fender Gold Sparkle Strat: has a Suhr plate added to the cavity to cancel hum and control the noise of the pickups.

2004 Black Fender Jeff Beck Strat: all original except for the Suhr hum-canceling plate added to the cavity.

2006 Gibson Custom Shop SG: all stock with P-90s; great sounding guitar.

1958 Gibson Les Paul: bridge pickup cover removed... enough said.

2004 Gold Fender Strat: stock except for the Suhr plate.

Amps:

1964 Marshall 8x10 cabinet

1969 Marshall Super Bass head (2)

1970 Marshall Super Lead heads

1950 Fender Bandmaster with original Jensen speakers

1963 Fender VibroVerb

1980s Fender Tone Master head

1973 Fender Dual Showman 1972 Fender Dual Showman

1973 Fender Bassman 2x15 cabinet with JBL speakers

Pedals:

Fulltone Tube Tape Echo

Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail Reverb

Electro-Harmonix POG

Ernie Ball Volume Pedal (controlling the POG volume)

Line 6 MM4 Modulation Effects

Line 6 DL4 Delay

Effects A siren (a custom-made pedal that is an actual siren)

Digitech Whammy

Fulltone Ultimate Octave

Dunlop/Custom Audio Electronics MC402 Boost Overdrive

Klon Centaur (original brown-cased)

Option 5 Destination Rotation Single

Cry Baby Jimi Hendrix Signature wah

Strings:

Pyramid strings - He uses different gauges for different guitars. He uses standard gauge 9-44 or 10-46. And he uses 11-48 for some of the guitars that have dropped down tunings…

Cables:

Belden Wire

Straps:

Custom Dunlop thin leather

Picks:

Dunlop 483 Classic Celluloid Heavy (custom imprinted)

Accesories:

Dunlop Joe Perry signature series Boneyard Slide

[Thanks to Trace Foster, Joe’s tech, for providing info on the touring gear, and special thanks to Jim Servis for his assistance in compiling this list of guitars]

Formed in 1970 in Boston, Aerosmith paid their early dues, played hard and partied harder, and enjoyed hits like “Walk This Way” and “Dream On.” In the summer of 1979, Perry, at odds with other members of the band, and dealing with the strain of increasing drug dependency, left Aerosmith to start The Joe Perry Project, a group with a rotating lineup that recorded three albums and toured almost constantly. With his personal and professional life a shambles, Perry and his friends in Aerosmith patched things up in 1984, got into rehab, cleaned up, and enjoyed 25 years of unprecedented success with a series of hit singles, MTV videos, critically-acclaimed albums and sold-out tours. Aerosmith have sold an astounding 150 million albums worldwide, and are members of The Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame.

But flash forward to Autumn 2009, and Aerosmith was once again in a state of confusion and turmoil. Lead singer Steven Tyler, eager to establish himself as a solo artist at age 61, decided to take an indefinite hiatus after falling off a stage this past summer. While rumors of the band’s demise abounded, Perry went on record saying that Aerosmith was still together, and might look for a replacement for Tyler. In the meantime, Perry, never one to sit still, and with a backlog of new material, quickly recorded and released an album in October called Have Guitar, Will Travel, featuring a newly handpicked group of musicians. Billed again as The Joe Perry Project, the band has just completed a short US tour, and is poised to take their act overseas within weeks of this writing, opening for Mötley Crüe and Bad Company.

A self-confessed ‘60s rock fan, guitar collector, horse enthusiast and gearhead, Joe spent time discussing his love of funky Supro guitars, and how he surprisingly plans to unload a significant portion of his vast collection in the coming year.

What was the spark that ignited your desire to play guitar?

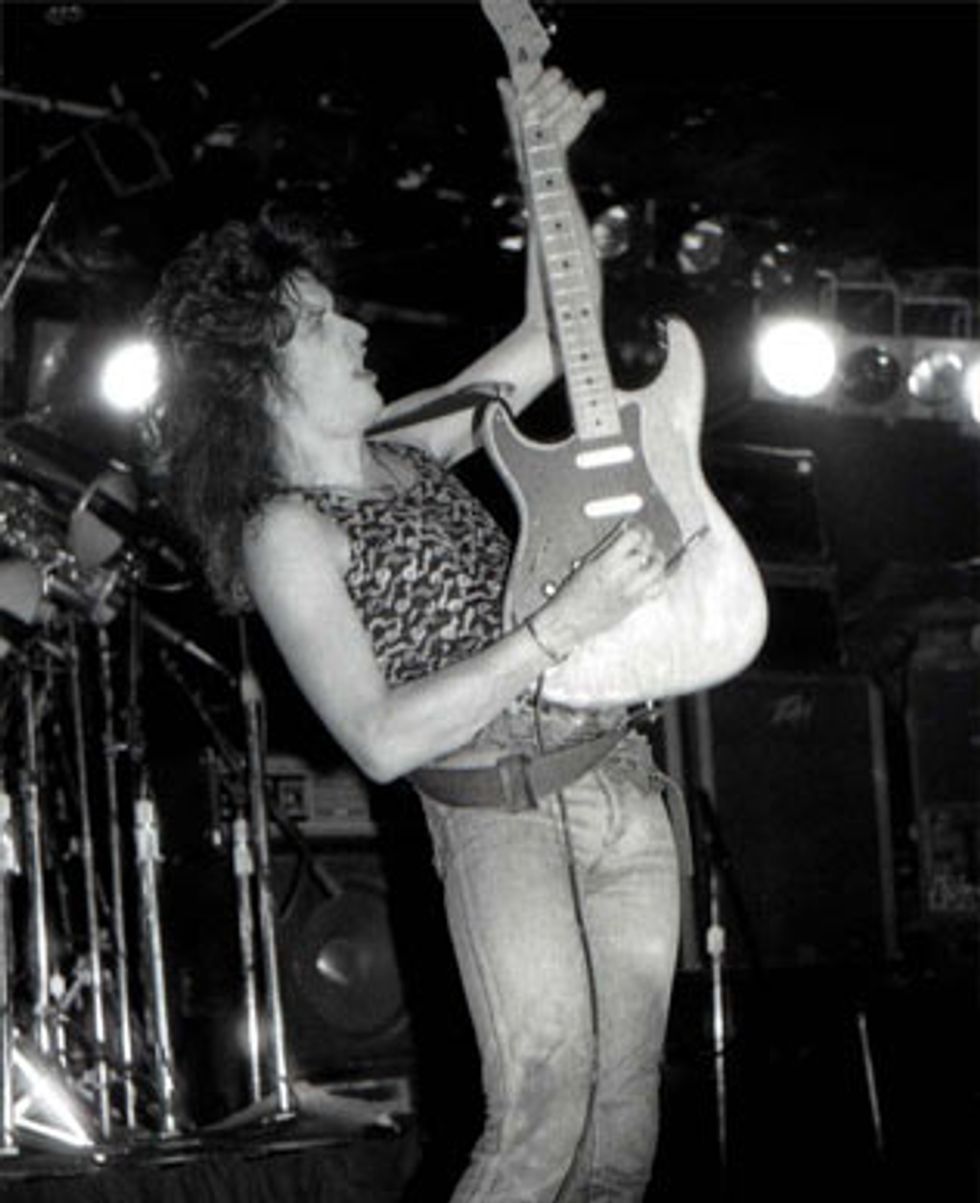

The Joe Perry Project performing at L’Amour, Brooklyn, NY, Sept. 30, 1983. Photo by Frank White |

Once I discovered The Beatles, their music and movies, and all the other British bands like The Stones and Yardbirds, I was captured by rock ‘n’ roll.

You were influenced by Jeff Beck and Jimi Hendrix specifically, but how did Peter Green fit into the equation?

A lot of English bands came to Boston before they hit New York back then. I guess they wanted to warm up first there. I had a friend who got a lot of free tickets to the Boston Tea Party club. Fleetwood Mac took up residence at the Tea Party for weeks on end, and I must have seen them thirty times or more. I saw them on great nights, terrible nights, nights when they were all drunk. Peter Green’s style, attitude and sound really got to me. These guys didn’t care about being rock stars. It was all about the music for them. I became a big fan of Fleetwood Mac. I guess you could say I was most influenced by the second wave of British bands, like The Yardbirds, Mac and The Who.

Did you ever see The Yardbirds live?

No, they had broken up by the time I started going to concerts. I wish I had seen them.

The first time I saw Aerosmith, you guys were opening for Mott The Hoople.

We toured with them a lot in the beginning. I can’t say enough nice things about those guys. They were very good to us. They took us under their wing, you might say. All they wanted to do was play rock ‘n’ roll and party. They’re back together with all the original members playing shows in England, and I heard they sound great.

Let’s talk specifically about guitars. What are you using on tour right now?

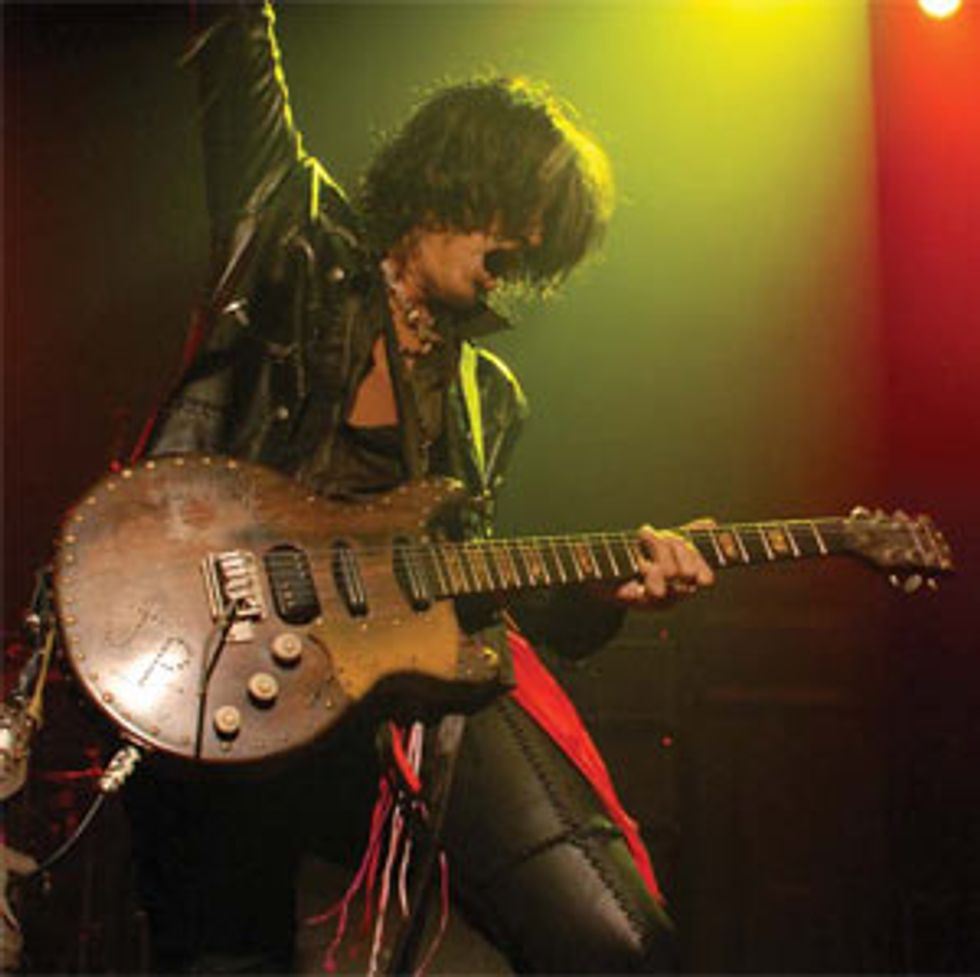

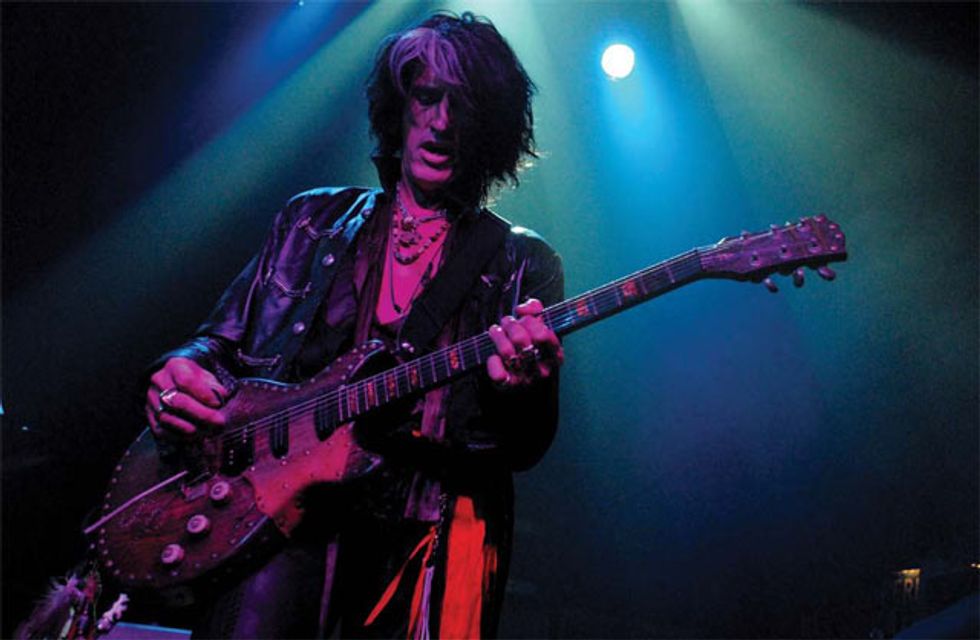

Performing at the Filmore at Irving Plaza, NYC, Nov. 10, 2009. Photo by Frank White |

Is that the brown guitar with the studs on the body?

Yes, that’s the one. I call it the Bones and Bullets guitar. There are pictures of it in the booklet of the new CD.

Performing at the Filmore at Irving Plaza, NYC, Nov. 10, 2009. Photo by Frank White

What makes a great guitar to you?

It’s the little things—the nut, the bridge, the setup. You know how it is: every guitar is different and some are just special. My Billie guitar rings like a bell when the volume is down. When you turn it up, you can get a great rock ‘n’ roll crunch, and it’s a good heavy metal guitar too. It does everything well. That guitar is really special.

How did the Billie guitar come about? I know several guitarists who speak fondly of it, for obvious reasons.

It started out as a standard B.B. King Lucille model, and I picked it because there were no F holes to get in the way of the artwork. It’s amazing that guitar plays as well as it does. I changed the electronics; it has one volume and one tone now. The inspiration was the nose art you saw on airplanes during World War II. I wanted to put the most beautiful woman I could find on there, so naturally, I chose my wife. I sent it out to an airbrush artist and he did a great job. When I got it back, I opened the case and gave it to Billie, and she hated it. She was so embarrassed she refused to come out of the dressing room at Aerosmith shows when I was using it. She couldn’t stand the sight of seeing herself on a 30- or 40-foot screen at shows. Now, she’s okay with it.

I read that you have about 600 guitars. What are some of the standout pieces from that collection? Which are your favorites and why?

It’s really closer to 500 guitars, and there are so many great ones. To tell you the truth, I want to unload a large portion of the collection. I’ve been working with Perry Margouleff [Author’s Note: Margouleff is a noted record producer and vintage guitar expert] on the best ways to disperse them. I want to sell a lot of them because they’re sitting in storage, I just don’t have time to play them all, and I’d rather get them into the hands of guitarists who will play and enjoy them. Some may go on consignment, others we’ll sell directly to collectors. Others we may donate to charities or give to kids.

Joe, do you have a Supro Dual-Tone you want to sell? That’s a guitar I’ve always wanted. Let’s talk about it when you get ready to sell, okay?

Yeah, I have two of them. Sure, no problem. We can do that.

You have two signature Les Paul models. How much input did you have in their design?

They let me decorate them; it was mostly about cosmetics. They’re pretty much standard Les Pauls. The first one has the black see-through finish. I wanted the flame top with that nice ripple effect you get. When light catches it, the flames come through. I had Gibson make them lightweight, and it has a Tonex pot on the neck pickup, which gives you a static wah sound. That’s a very cool effect for solos. The Boneyard model is custom shop Gibson. My wife is an artist who’s had experience working in multimedia visual arts, and she had an idea for the finish to bring out the tiger stripe effect. We were at the Gibson custom shop and she explained the idea to the guys there. Their response was, “That won’t work.” They tried to talk her out of it. She said, “Can’t you just try it this way?” They did, and it worked. It really brought out the wood grain. The top is sort of a greenish-orange shade, and the flame top is very prominent.

I also saw a recent promo photo of you playing a black Gretsch. How do you use it?

That guitar is a real squealer. It’s a Black Falcon. It feeds back too much live. I used a White Falcon on that cut from the new album, “Somebody’s Gonna’ Get Their Head Kicked In Tonight.” Gretsches are good rockabilly guitars. Fred Gretsch gave me the White Falcon I have.

I read somewhere that you have a lot of cheap, funky electrics like Teiscos, Supros and Danelectros. Is that true?

Yeah, those cheap guitars are so much fun to play and collect. I love the Supro Ozark model. I have two of them. I think the Ozark is the best slide guitar ever made. It’s got a flat fretboard, like the Dan Armstrong see-through, and I think that factor makes them both great slide guitars. I have written songs especially for the Ozark. The pickups on the Ozarks go over and under the strings, and the sustain is amazing. The old Rickenbacker horseshoe pickups were similar but not quite the same. There are so many variations to those old Supro guitars. No two are ever alike.

I have a red Supro Belmont I bought from a kid this past summer for $250. I had it rewired and set up for slide by David Petillo. It’s a killer. Those old Belmonts are cool too. Supros are just the best slide guitars.

What's your onstange amp rig right now?

I’ve always liked something that’s crunchy and something that’s clean, so it’s usually a combination of Marshall and Fender. I use a ’64 50-watt Plexi with an 8x10 Marshall cabinet, a ’69 Marshall Super Bass Plexi head, plus a couple of Dual Showman amps with two 15s. I also have a ’50 Bandmaster Tweed with original Jensens that smooths out and melds the sounds together. There are other amps we use onstage too. In the studio, I’ll use a Fender Champ or an old Epiphone amp with an 8" speaker.

What’s on your pedalboard right now?

I’ve got a Fulltone Echoplex reissue, a Fulltone Ultimate Octave, an Electro- Harmonix Holy Grail Reverb, a blue Line 6 Modeler, a green Line 6 Delay, an Ernie Ball volume pedal, a DigiTech Whammy pedal, an original Klon Centaur, a Jimi Hendrix Signature Cry Baby wah and other stuff. The pedalboard is pretty extensive. One of the coolest things I have on there is an actual siren built into a pedal.

Premier Guitar’s motto is “the relentless pursuit of tone.” How would you define good tone?

Good tone is what works for the song. Your tone forms the basis of each song. Basically, there is no bad tone, just bad uses of tone. What’s good for one song can be bad for others. I use lots of different tones depending on the material.

The tracks I’ve heard from your latest CD have a very raw, dense quality, as if the band recorded together in the same room, the way it was done in the late sixties. Was that the vibe you were going for this time? You recorded this disc in your home studio, right?

That’s exactly what we were going for. We isolated the guitars just enough and everybody played at the same time going for keepers. With this record, we went for good takes every time. If someone screwed up, we did another take or pieced things together. The whole vibe was about getting good takes. The musicians I have now allowed me to operate that way, and it worked out real well. Aerosmith recorded Honkin’ On Bobo in my studio the same way. I’ve always had a home studio. In the beginning, it was just basic four-track stuff, but now, I have a great studio at my disposal all the time.

I frequently hear older musicians complain that there are no young guitar heroes. Are there any young guitarists you like?

I really like Jack White. He plays stuff that sounds like an exercise, but you can tell he’s listened to blues guys like John Lee Hooker. I hear the same thing when I listen to things my sons play—simple riffs, but you know they can develop what they’re doing if they work on it. Jack White will have longetivity. There are a lot of good young technical players out there.

Do you have any final words of wisdom and advice for guitarists?

Practice with a metronome. They’re cheap, you can buy one that attaches to your guitar strap, and they’re great for developing your time and feel. Every guitarist, every musician, should work with a metronome or a click track to develop a good sense of time.

Joe Perry’s Gear for the Joe Perry Project Tour 2009/2010

Left to right: Joe Perry Boneyard Gibson Les Paul, Gibson Custom Shop Les Paul Joe Perry Model (stock), 2000 Dan Armstrong Plexi, "Billie Perry" custom ES-335 Lucille, Mid-'50s Supro Ozark

Left to right: Joe Perry Boneyard Gibson Les Paul, Gibson Custom Shop Les Paul Joe Perry Model (stock), 2000 Dan Armstrong Plexi, "Billie Perry" custom ES-335 Lucille, Mid-'50s Supro OzarkGuitars:

“Billie Perry” custom Gibson ES-335 Lucille: a one-of-a-kind guitar with his wife Billie’s picture on it, and one of Joe’s all time favorite guitars. Boneyard Green tiger Gibson Les Paul with a bigsby tailpiece, stock: the prototype Boneyard Les Paul; it says “prototype” on the back of the headstock.

“Bullets and Bones” guitar: custom-made for Joe by R.S. Guitarworks; features a Lindy Fralin P-90 pickup in the bridge, Joe Barden pickups in the middle and neck, and a Trem King tremolo.

2000 Dan Armstrong Plexi: nothing says open-tuning slide guitar like this Plexi.

Mid-‘50s Supro Ozark: used for slide work only.

Black Gibson Les Paul: Custom Shop Joe Perry model, stock.

Gretsch White Falcon: given to Joe by Fred Gretsch Jr.

Ernie Ball Silhouette Guitar: mid-‘90s alloriginal with a Trem King tremolo.

Mid-‘70s Left-Handed Strat with reverse Telecaster headstock: the actual guitar from the first Joe Perry Project tour, and one of the guitars Joe has owned the longest. It has Barcus Berry pickups in it.

Left-Handed Fender Jim Servis/Joe Perry strat: loving referred to as “Frankenstrat,” and built by Joe and Jim Servis. It’s basically a parts guitar that has literally been in a fire; a left-handed Fender body and a reverse Tele Warmoth neck, Barden pickups custom-wound for hotter output, and a really cool green pickguard.

1992 Fender Gold Sparkle Strat: has a Suhr plate added to the cavity to cancel hum and control the noise of the pickups.

2004 Black Fender Jeff Beck Strat: all original except for the Suhr hum-canceling plate added to the cavity.

2006 Gibson Custom Shop SG: all stock with P-90s; great sounding guitar.

1958 Gibson Les Paul: bridge pickup cover removed... enough said.

2004 Gold Fender Strat: stock except for the Suhr plate.

Amps:

1964 Marshall 8x10 cabinet

1969 Marshall Super Bass head (2)

1970 Marshall Super Lead heads

1950 Fender Bandmaster with original Jensen speakers

1963 Fender VibroVerb

1980s Fender Tone Master head

1973 Fender Dual Showman 1972 Fender Dual Showman

1973 Fender Bassman 2x15 cabinet with JBL speakers

Pedals:

Fulltone Tube Tape Echo

Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail Reverb

Electro-Harmonix POG

Ernie Ball Volume Pedal (controlling the POG volume)

Line 6 MM4 Modulation Effects

Line 6 DL4 Delay

Effects A siren (a custom-made pedal that is an actual siren)

Digitech Whammy

Fulltone Ultimate Octave

Dunlop/Custom Audio Electronics MC402 Boost Overdrive

Klon Centaur (original brown-cased)

Option 5 Destination Rotation Single

Cry Baby Jimi Hendrix Signature wah

Strings:

Pyramid strings - He uses different gauges for different guitars. He uses standard gauge 9-44 or 10-46. And he uses 11-48 for some of the guitars that have dropped down tunings…

Cables:

Belden Wire

Straps:

Custom Dunlop thin leather

Picks:

Dunlop 483 Classic Celluloid Heavy (custom imprinted)

Accesories:

Dunlop Joe Perry signature series Boneyard Slide

[Thanks to Trace Foster, Joe’s tech, for providing info on the touring gear, and special thanks to Jim Servis for his assistance in compiling this list of guitars]

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)