Beginner

Beginner

• Develop the skills to quickly and accurately write a chart for a song.

• Learn how to transpose songs to any key.

• Understand basic functional harmony.

Do you want to be able to chart songs lightning fast? Do you want to be able to play your favorite song in any key? Do you want to be able to stand onstage and get through a song you’ve never even heard before and do it justice? If so, the Nashville number system will be your new best friend.

The Nashville number system is a shorthand way to write charts for songs. Everyone in this town uses it. Once you know it and become adept at hearing intervals you can chart songs while listening to them on an airplane with no instrument in sight. And instead of remembering how many sharps or flats are in a key as you’re hollering chords to your buddy during a show, you just shout out or flash the corresponding numbers and throw your cares away.

Disclaimer: It’s much easier to explain these things along with a video so you can actually hear what’s happening. Read this lesson and then watch the video at the end to fully understand how notes turn into numbers.

I could simply write a decoder key to show you how to convert letters to numbers, but there’s a lot of musical information that is implied in this system. So, you need to understand how and why the number system works so you can make it work for you. I want you to use it, by gum! Your life (and mine) will be so much easier if you do.

Let’s start at the beginning.

We have to go back to basics and revisit the foundation of modern music: the major scale, which is also known as the Ionian mode. Music is based around scales. Songs are simply a collection of chords built upon notes within a scale, usually the major scale. In the number system, we’re simply eliminating the letter names of the notes and changing them to numbers instead.

The key of C is so great. On a piano it’s only white keys—no surprises. You can instantly play it. You feel great about yourself. Easy peasy. Using a piano, play a C major scale. Sing the note letters as you play: “C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C.” Play the scale again, only instead of singing the letters, sing these numbers: “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 1.”

When you get back to C, sing the number 1 again. Remember Julie Andrews in the Sound of Music? “That will bring us back to Do!” From henceforth, C will be known as the number 1, as long as you’re in the key of C, that is.

All About Those Chords

To understand the Nashville system, you need to understand which chords are always written as major and which chords are always written as minor. You might have noticed that certain chords in a common progression usually tend to be major and certain chords tend to be minor. For example, if you’re playing a blues in the key of C major, C is a major chord. If someone throws in a turnaround you might find yourself playing an Am to a Dm to a G and back to C. But why?

Let’s play some chords on the keyboard. To make a triad, which is a chord made of three notes, put your thumb on middle C, your middle finger on E, and your pinky on G. That’s a C major chord. Play it loud and strong and enjoy its life-affirming, uplifting major-ness. (Or watch me do it at 4:40 in the video.) Now, take that same finger pattern, pick up your hand and move it up the scale to the note next door, plopping your thumb on D, middle finger on F, and pinky on A. You’re now playing a Dm chord. It’s not as life-affirming. In fact, it’s eerie and a bit melancholy—according to Spinal Tap's Nigel Tufnel, Dm is the saddest sound in music.

Keep moving this triad pattern note by note up the scale until you get to the C an octave above where you started. As you do, the chord types will change. Here are the triads you’re gonna get if you stay in the scale:

C (C–E–G)

Dm (D–F–A)

Em (E–G–B)

F (F–A–C)

G (G–B–D)

Am (A–C–E)

Bdim (B–D–F)

Ear training tip: Do this all the time and train your ear to really hear the difference between the way major and minor chords sound. Close your eyes and have a friend play the chords for you and see if you can tell the difference between major and minor triads within the C major scale. Keep it up and you’ll be driving everyone crazy naming majors and minors as you hear them on the radio. Fun!

Implied Knowledge

These major and minor triads give us a valuable clue into understanding implications within the number system. When you’re looking at a number chart each number refers to an entire chord. It’s implied that when you see a 1 on the chart it will be a major chord, 2 will be minor, and so on. This follows the pattern we established above, when harmonizing the C major scale using triads:

1 major

2 minor

3 minor

4 major

5 major

6 minor

7 diminished

When you’re writing a number chart, it’s assumed that you understand the inherent major or minor-ness of the chords. The number 2 will have a dash next to it, which means the chord is minor. Remember, in a major scale the second chord in the scale is always a minor chord. The number 1, the first chord of your major scale, won’t have a dash. The lack of a dash implies that the chord is a major chord.

But what if some smarty pants songwriter decides to throw in a major 2 chord instead of a minor 2 just for fun? In the key of C, this would indicate a D major chord and there ain’t no F# in the key of C major. Simple. Just remove the dash and write “2maj” so you’ll know what’s up.

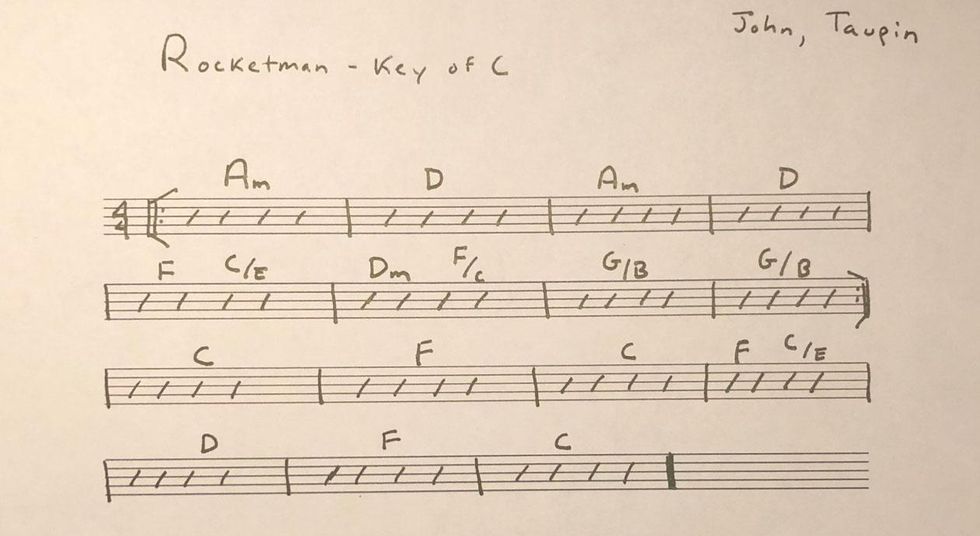

Elton John’s chorus of “Rocket Man” is a brilliant example of how to tastefully use a major 2 chord. In Ex. 1 you can see a simple chart of this tune that uses traditional chord symbols.

Ex. 1

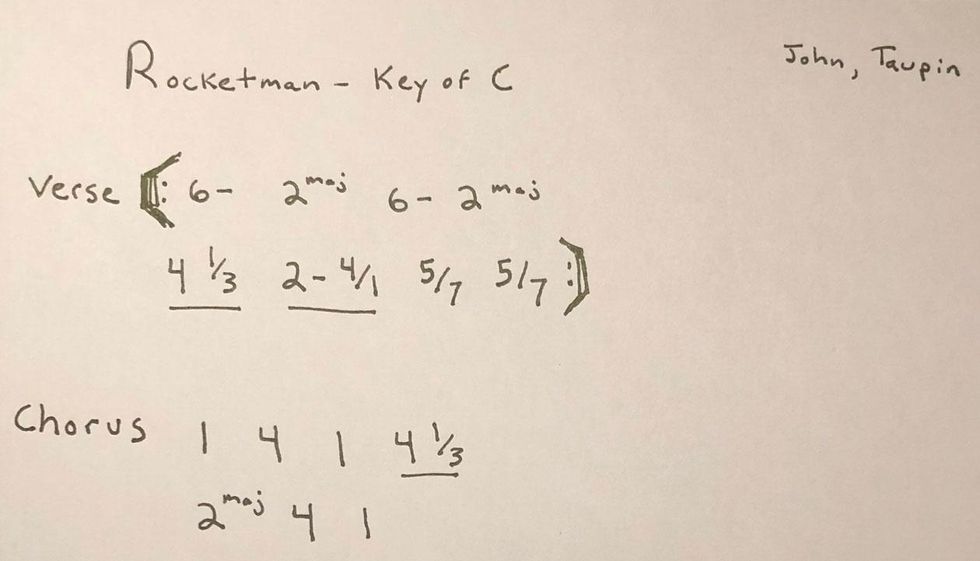

Using the method we described above, you end up with Ex. 2, which is a Nashville-style chart of the identical chord progression in Ex. 1.

Ex. 2

Follow along with this video so you can hear the chords going by along with the chart.

Elton John - Rocket Man (Official Music Video)

Never Rewrite Charts Again

It doesn’t matter what key your song is in—this chart will work. This is the whole point of the number system. If someone wants to change the song’s key, all you have to do is write the new key at the top of your chart. Nothing else on your chart has to change. Ahh. So functional.

What about Minor Keys?

In the number system, there’s no such thing as charting a song in a “minor key.” Because even if you’re in a “minor key,” you’re still playing the same chords within the Ionian major scale. Let me explain.

Every major scale has a relative minor scale that’s based on the sixth degree. For example, the relative minor of C major is A minor. Now, go back to your piano. If you play an A natural minor scale (A–B–C–D–E–F–G) you’ll notice that it has exactly the same notes as a C major scale, just in a different order. You jumped in the same pool from a different angle. You turned a smile upside down into a frown, taking happy sparkly major action and darkening the skies just by starting on a different spot in your scale. When you play the same notes of any major scale but start from the sixth note of that scale, the order in which the whole- and half-steps fall adds up to a natural minor scale. You can hear it.

Since the notes are the same as in the major scale, the corresponding numbers in your number chart are the same. You’re just starting your song from a different spot on the scale. And now everyone’s crying.

If your song is in a “minor key,” you wouldn’t kick off your chart with a 1-. That would completely negate the inherent chord values of the number system, you’d be throwing in major 2s and 3s all over the place, and the whole chart would be a huge mess. Nope. Your song would simply start on the 6-. Same pool, different diving board.

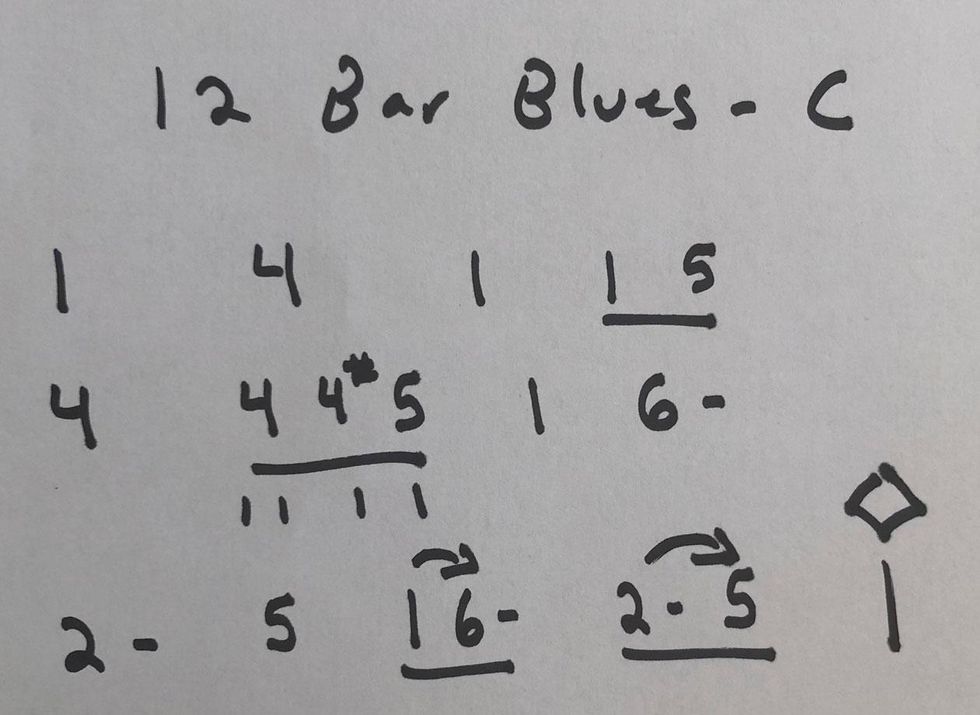

A great place to start understanding all of this is over a 12-bar blues. Most players get their start by learning the blues, and for good reason. The chord progressions have a familiarity to them. Your ear knows what type of chord it wants to hear next, and for the most part you only have to learn three chords.

In the key of C, those chords are C, F, and G. Now to make them “blue,” you gotta throw a b7 in there to make them dominant. You need to indicate this blueness on your number chart, so you write a tiny 7 next to your number, just like you do with a letter chart.

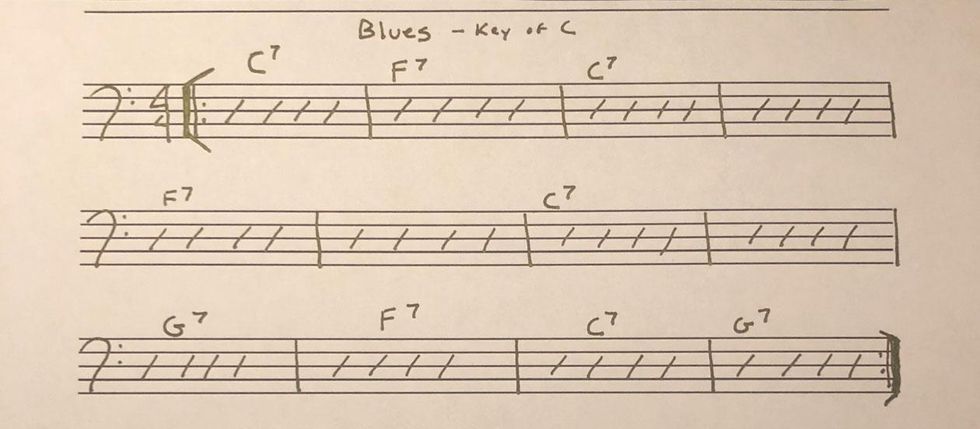

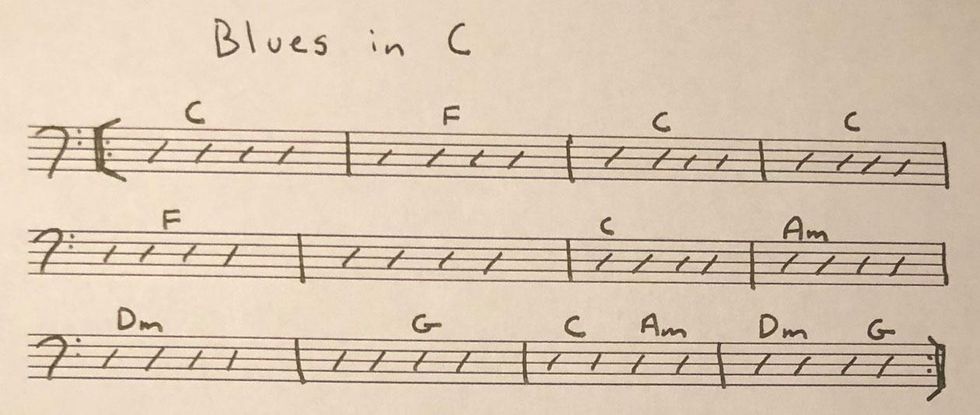

Ex. 3 shows a simple blues progression with chord symbols.

Ex. 3

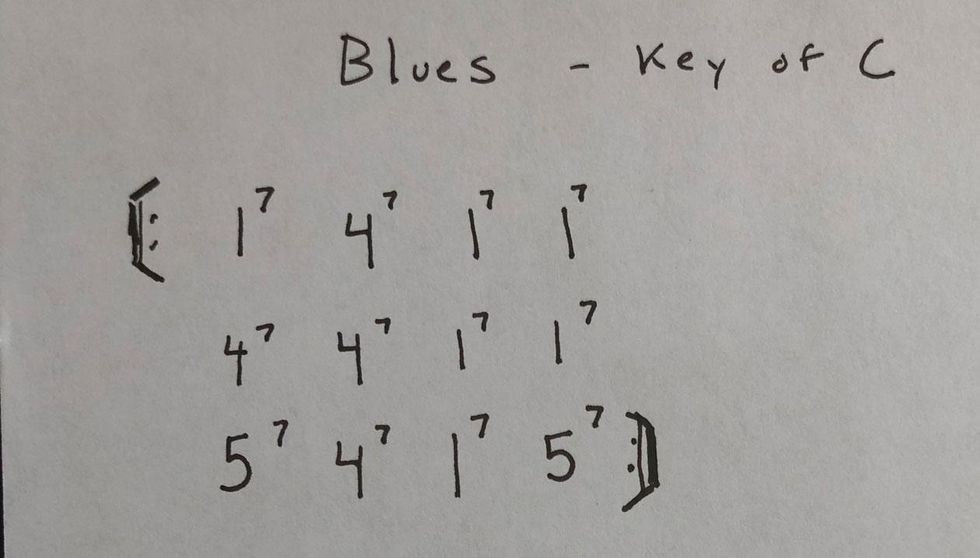

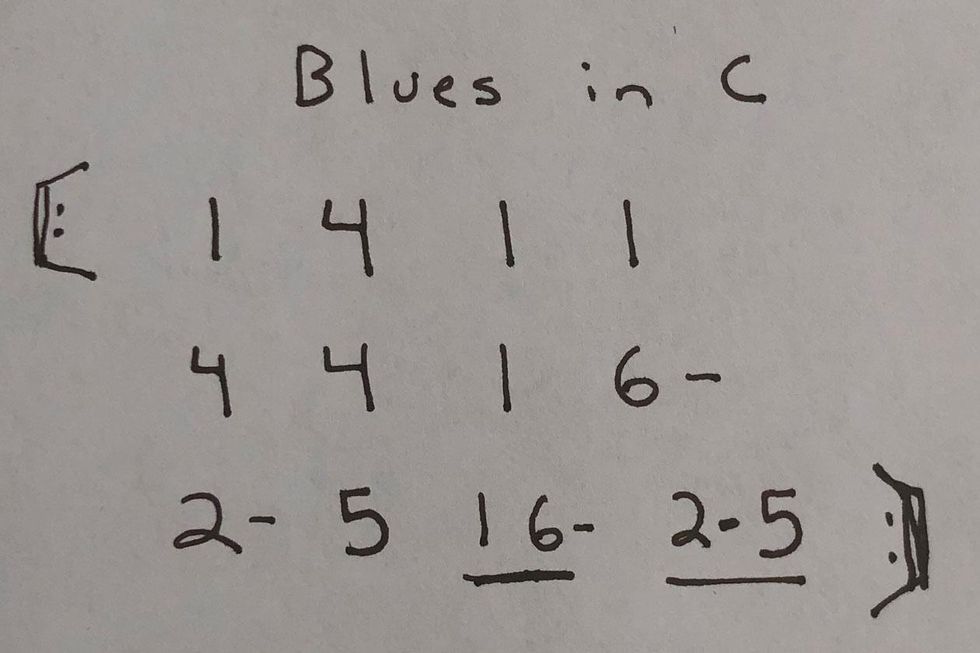

Here is the same blues progression written in numbers (Ex. 4).

Ex. 4

Changing Keys

What happens if your singer decides to sing the song in a new key? On a letter chart you would have to change every chord. Literally sit there and cross out every chord and write new letters in its place. No bueno.

On a number chart, just cross out that “C” and scribble in the new song key. And forget about trying to rewrite letter charts onstage. I’m in an all-female cover band. We take requests. If someone wants to hear a Tim McGraw tune, it’s unlikely we’re gonna be playing it in the key in which it was originally sung by Mr. McGraw. But if I frantically look up the chords to “Something Like That” on my phone as the drummer is counting it off, all I’ll find are letter charts written in Tim’s original key.

It’s a tremendous pain in my rear to have to transcribe letter charts up or down several steps in real time when I’m out on a gig. If the whole world would adopt the number system, many professional musicians’ lives would be so much easier. That’s why I’m spreading the good word here, folks. Get onboard!

Beat Values

The other thing you’ll notice with number charts is that there’s no staff paper. Staff paper allows the depiction of measures of music, notating rhythms, etc. The number system is a shorthand, so those depictions are either eliminated or implied. With the number system it’s understood that each number written on your chart is given the value of one measure of music. In 4/4 time, that’s a total of four beats per number on the chart.

But what if a chord changes within two beats?

Calm down, we’ve got you covered. In our nomenclature we call a measure of music divided into two or more chords a “split bar.” To indicate that a single measure of music contains multiple chords, you simply underline all the chords within the measure, tying them together in musical matrimony.

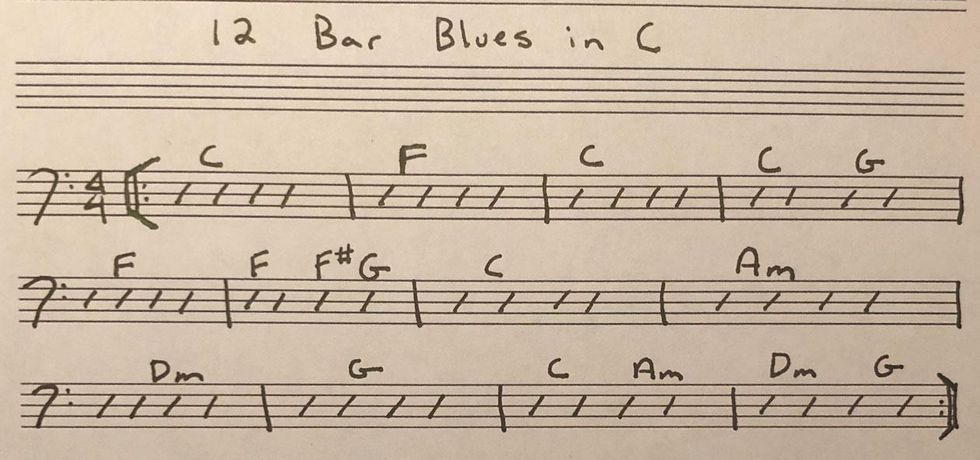

Back to the blues! In Ex. 5 I’ve updated our blues in C with a few split bars.Ex. 5

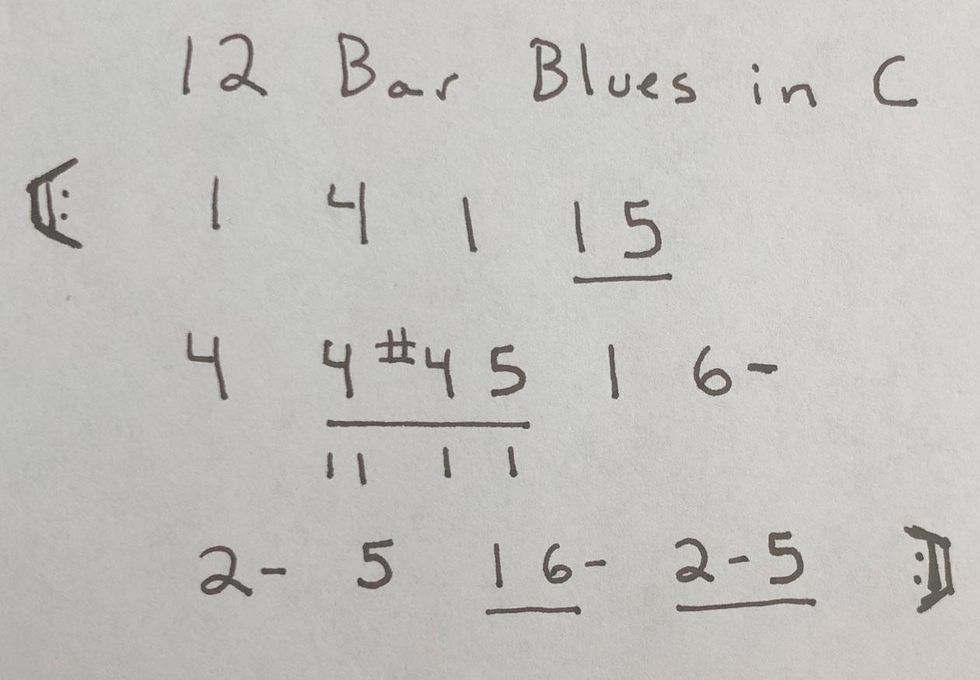

And now, in numbers (Ex. 6).

Ex. 6

If you see two numbers underlined, you split the measure equally between them. In our turnaround at the end of the progression, the C chord gets two beats, the Am gets two beats, then we head to the next measure where the Dm gets two beats and the G gets two beats. Make sense?

What about chords getting one beat within a measure?

Relax, I got you. Say you want to throw some passing chords getting one beat into this blues progression. This is how we do it (Ex. 7 and Ex. 8).Ex. 7

Ex. 8

As you can see, just underline all chords within a single bar. Just write in some tick marks underneath the chords to show how many beats each chord gets. One tick mark equals one beat.

Riffs and Rhythms

This being a shorthand, certain things will be less available. You’re not using staff paper, so notating a specific riff you’d like to remember becomes more difficult. I will freehand draw a staff and write out riffs on occasion if they’re super-essential and I can’t remember them. (If I can remember them, I’ll just write the word “riff” in the spot where it takes place.) As a bassist, I usually just write out the rhythm of the bass part at the top of the chart next to the first chord and that’s enough to carry me through the whole song.

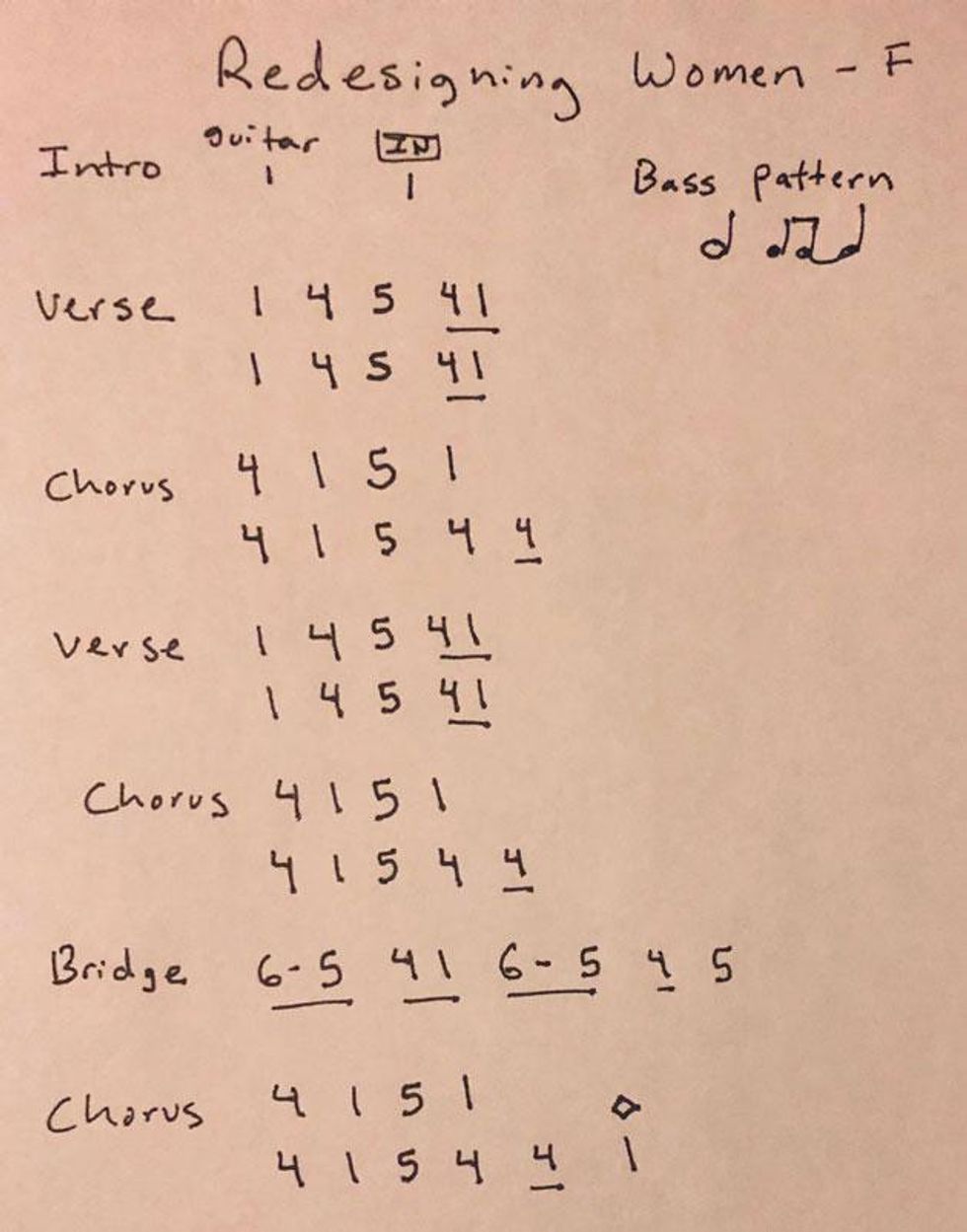

Here’s a chart (Ex. 9) I wrote for the song “Redesigning Women.” Check out my previous PG lesson to watch me write out this number chart in real time as I’m listening to the song. You can compare it to a traditional chart I wrote, which will hopefully help you understand the shorthand even better!

Ex. 9

There are many other symbols used in the number system. Everyone’s shorthand is a little different. The point is to write charts quickly in a way that you can understand (and read from the dirty floor of the club if you don’t want anyone knowing you’re looking at a chart).

Diamonds. A diamond drawn over a number indicates that the chord is to be played as a whole-note and will ring out over all four beats of the measure.

Arrows. Arrows generally indicate pushes (felt as anticipations) and are used the same way that a tie is used to tie two bars together.

Ex. 10 adds a diamond and arrows to our blues in C chart.

Ex. 10

It can take a minute to get the hang of this system, but once you do, you will positively tear through your chart writing. To grasp this system and to train your ear, sing along with your major scales as you practice. This will reinforce the fact that, though the note’s letter names change key by key, their numeric equivalents stay the same, no matter what key you’re in.

When I toured with Amos Lee, all the guitars (and my basses) were tuned down a half-step from standard tuning. The pianos and organs were of course in standard tuning, and then we had horn players on top of that. Trying to tell people what chords to play if you weren’t playing their particular instrument was extremely frustrating if we weren’t speaking in terms of numbers. This system is so handy for people using alternate tunings, for taking requests onstage and needing to be told the progression as it’s literally unfolding, and for changing keys in an emergency situation. It really is a Rosetta Stone for sharing music in the real world of working, professional musicians.

I hope this helps!