Chops: Beginner

Theory: Beginner

Lesson Overview:

• Understand the basics of the Nashville Number System.

• Learn how to create charts quickly and effectively.

• Create accurate, readable charts for the rest of your band.

Throughout my career as a guitarist, I’ve received plenty of last-minute calls to cover a gig or session. I’ve heard everything from “Can you cover this session for me on Friday?” to “Can you fly to Los Angeles and do the Jay Leno show on Friday?” Such calls usually come a day or two beforehand.

Dealing with this kind of pressure is part of being a professional guitarist. If you’re going to accept the gig, then you have to be able to deliver. As a result of these calls I’ve grown musically and I’m used to virtually any type of situation. One way I’ve been able to pull it off is by using charts and cheat sheets to learn lots of material in a short time.

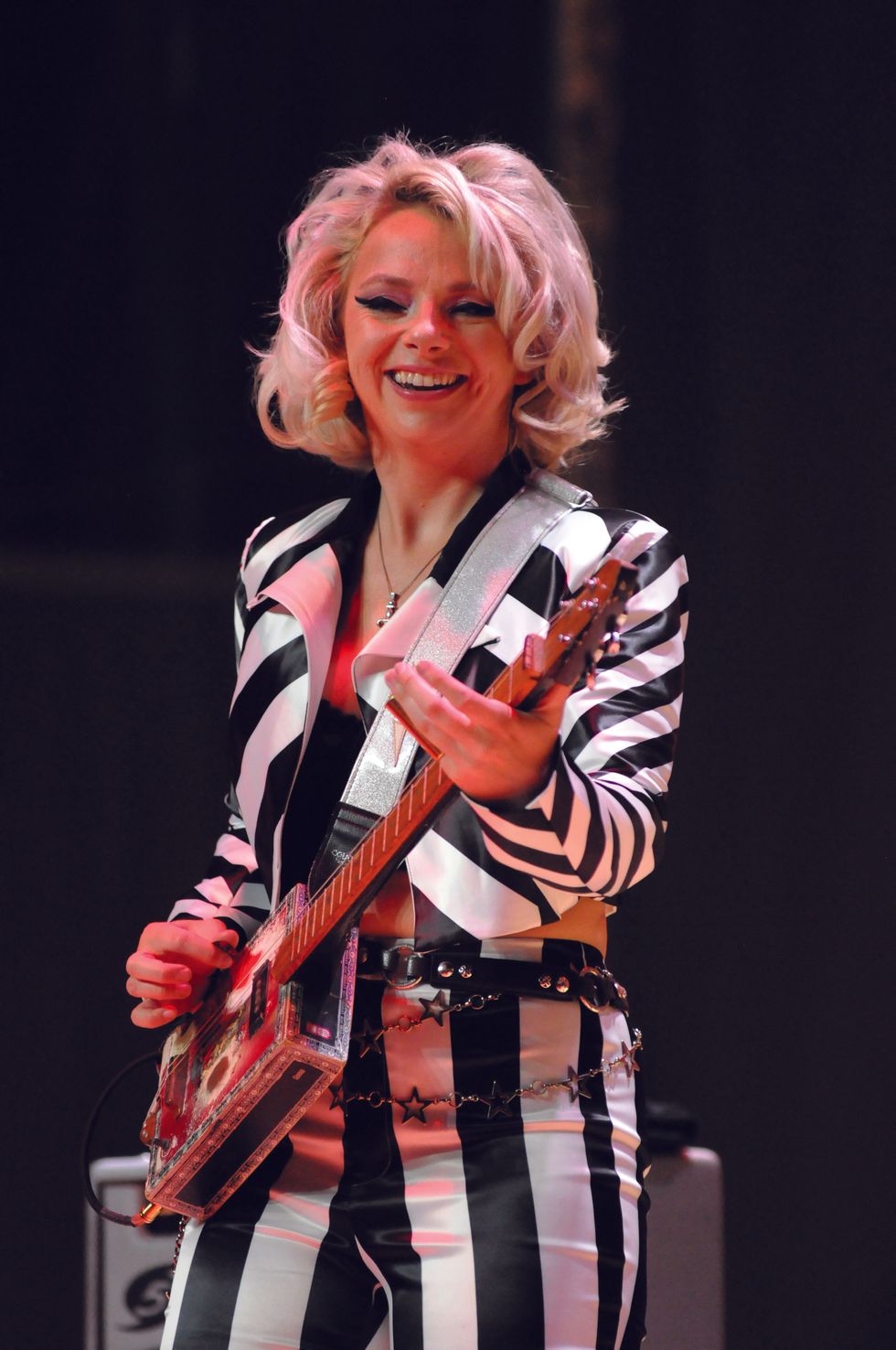

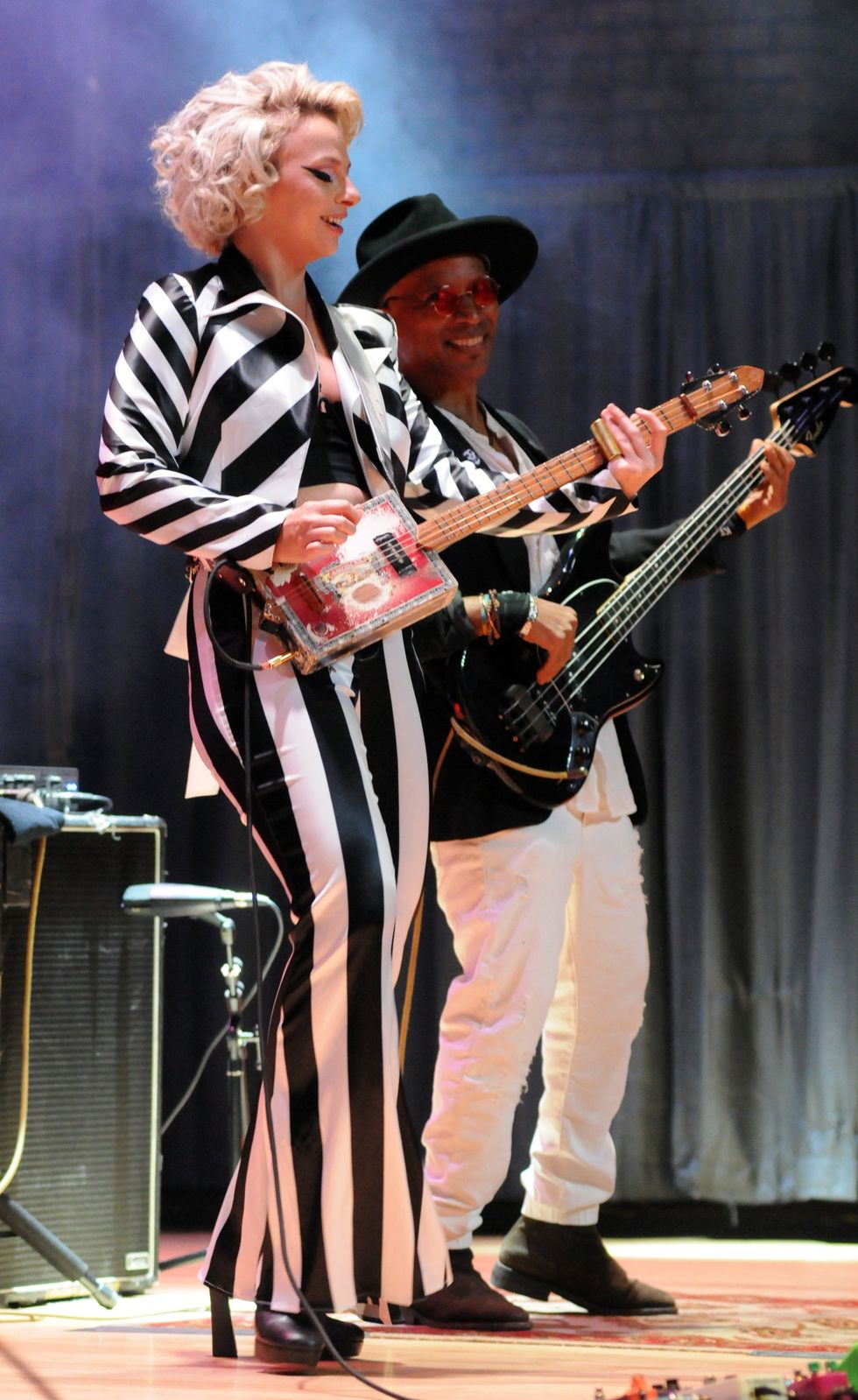

I’m currently working as the guitarist and musical director on the TV show Live from Daryl’s House. This means not only must I learn the songs for all the various artists, but I’m also responsible for writing charts and arrangements for the other guys in the band, doing the occasional horn arrangements, and creating lyric and chord charts for Daryl Hall and often the artists themselves. In this lesson, I’d like to share how I use charts and musical “shorthand” in real-life situations to get me through some of these last-minute calls.

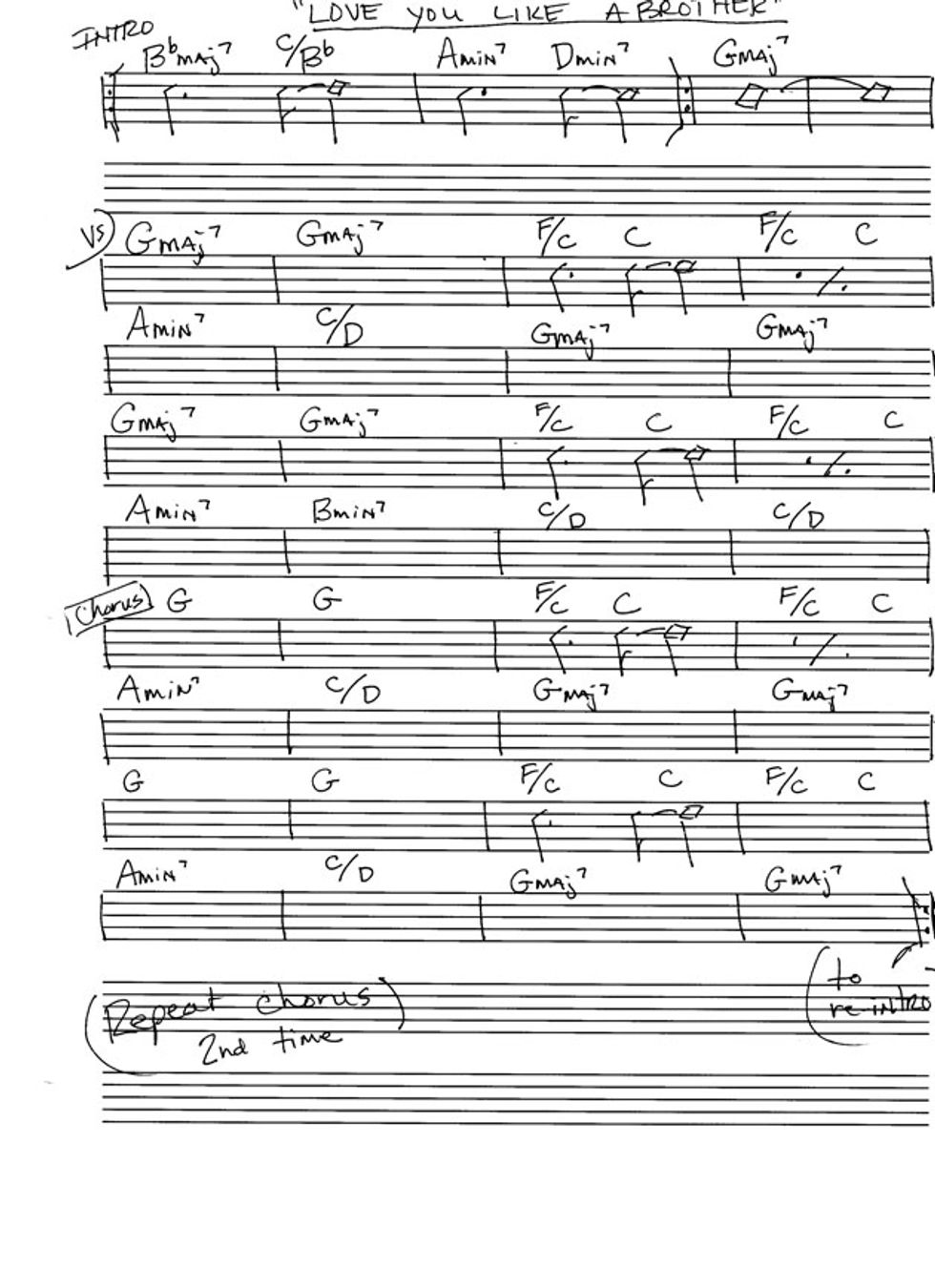

Rough Chord Charts

When I’m dealing with a simple arrangement and I know the musicians are going to cover all the parts, I’ll often just write a simple chord chart. It’s not the prettiest chart, but the chords and form are correct, so it will get the job done. In Ex. 1 you can see a chart I wrote up for “Love You Like a Brother.” We played this with the legendary Billy Gibbons on Live from Daryl’s House. If there are more intricate parts, I’ll use Sibelius to make the charts cleaner.

Nashville Number System Decoded

During the 10 years I spent working in Nashville as a studio player, I picked up a lot of tips and methods for some musical shorthand techniques. One of these is more commonly known as the Nashville Number System. Originally developed by the Nashville studio players in the ’50s, it’s a simple but ingenious system of writing out chord progressions by using the corresponding numbers based around the harmonized major scale.

For example, a G–C–D progression in the key of G would be written as 1 4 5. A C–Am–Dm–G progression would be 1 6- 2- 5 (the minus signs indicate minor chords).

The beauty of this system is that if a singer comes into a session and says, “That key is too high. Can you move it to Gb?” you won’t need to transpose any letters in your head, you can just adjust the chords while looking at the same harmonic movement. It does have its limitations though. I wouldn’t try to write out a Steely Dan tune with this system, and key changes within a tune are often awkward. Once you learn to hear root movements, you will eventually get to the point where you will be able to write out charts very quickly without an instrument.

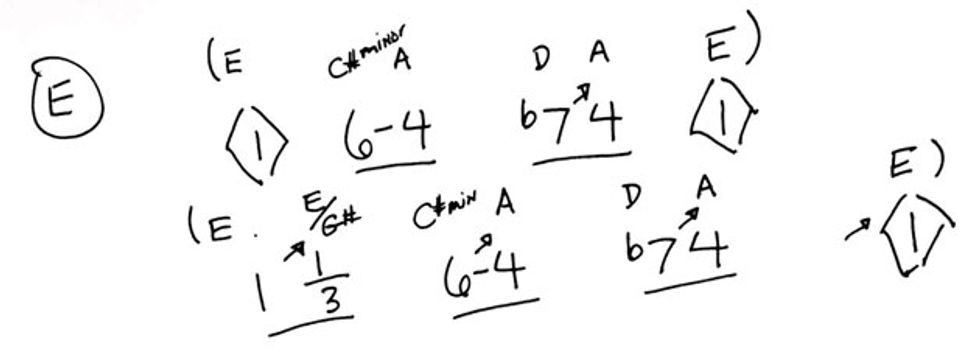

The simple progression in Ex. 2 is in the key of E. Above each symbol I’ve written the chord name to help decipher what everything means. In the first measure, you’ll see a 1 with a diamond around it. The diamond is meant to symbolize a whole note, so let the chord ring through the entire measure. Although there are variations on this, whenever you see two chords in one measure, each chord is either underlined or written in parentheses. You can also use dots on top of each number to denote beat placement. And remember, as we saw a moment ago, a minus sign or dash on the right side of a number means to play it as a minor chord. In this example, that’s a C#m.

In the third measure, notice a scraggly little arrow going from the b7 to the 4. Sometimes these are called “pushes” where you anticipate the second chord by playing on the “and” of beat 2. Remember: Each chord gets two beats when they are underlined.

The final symbol to check out in this example is the 1/3 in the fifth measure. This is a quick way to notate specific voicings or inversions of chords. Here, we play an E major chord with a G# (the 3) in the bass.

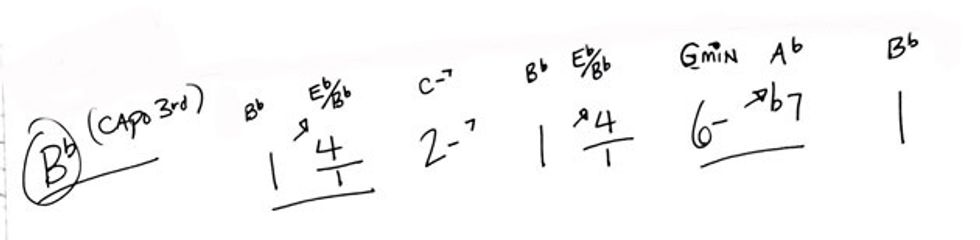

I moved to the key of Bb for Ex. 3. As you can see, we’re capoed at the 3rd fret (which makes this progression actually in the key of Db). This is something you could easily run into on a songwriter session.

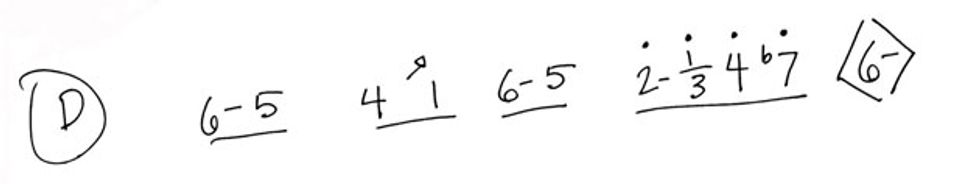

Ex. 4 is our final example of the Nashville system. Nothing new here, except for the fourth measure. Here, we are walking up to the 6- chord in the final measure. Each chord gets one beat (indicated by the dots above each chord). Although this is a minor-sounding progression, everything relates to the major scale. This is very similar to what you would see on a Nashville session.

Living in the Real World

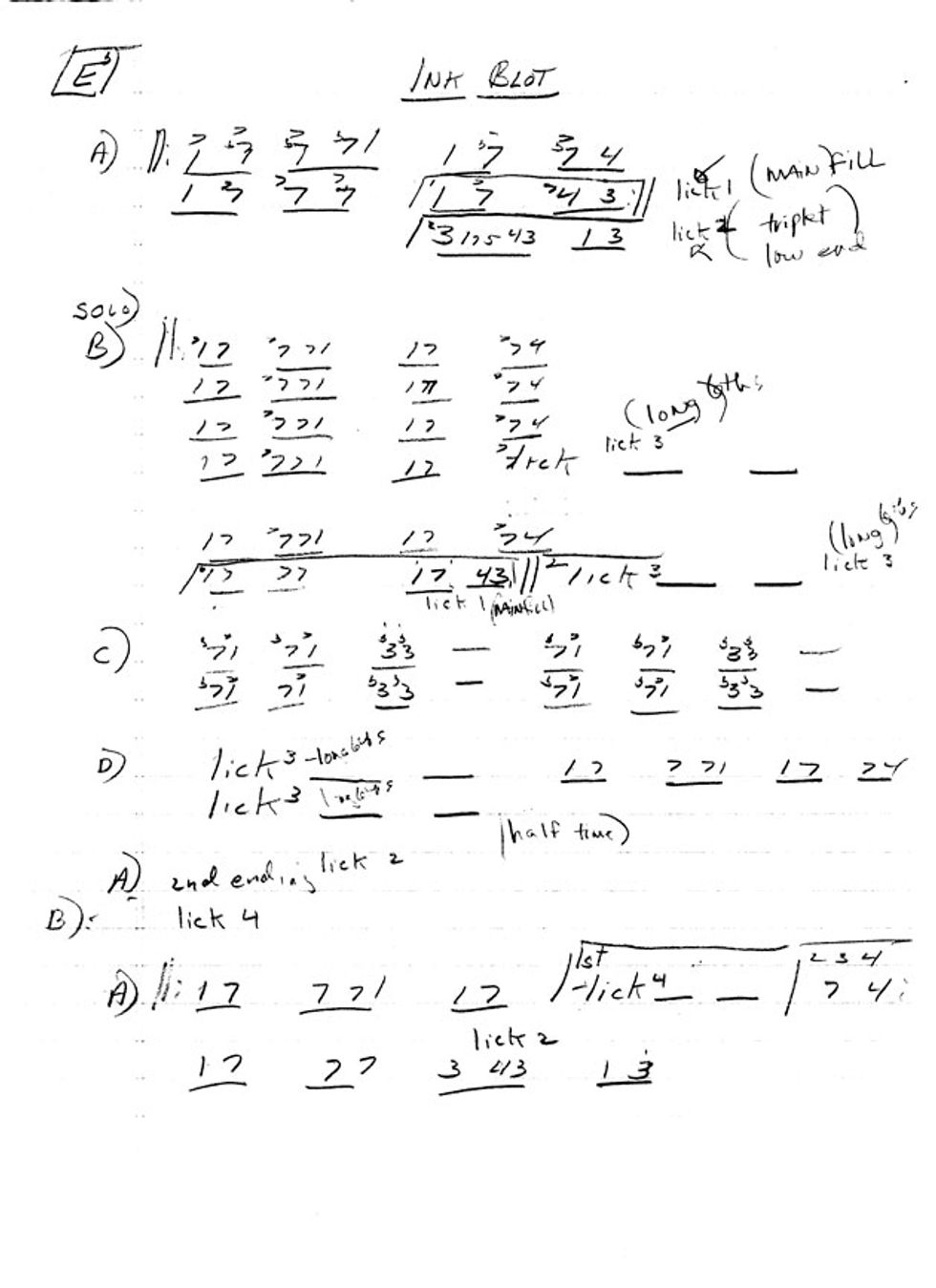

Last year I was on vacation in Japan with my wife when I got a call from Larry Carlton’s manager who informed me that Larry’s bassist (who is also Larry’s son) was sick and couldn’t make the tour. I was hired to go in and play bass with Larry, and this meant I had exactly one afternoon and night to learn his set before the rehearsal the next day (and the Tokyo Jazz Fest the day after that). I got all the MP3s and some of the charts, but I had to chart out most of the tunes myself. My chart for “Ink Blot 11” from Larry’s Fire Wire album was in the set. Ex. 5 is the chart I made to cram for that tour.

This tune has a variation of a lick on each time through the repeats. I memorized each lick and instead of writing it out, just came up with a name (“Triplet,” “Low end,” and “Long 6ths”) for each variation. This would be an example of using a chart just for chord and song structure, since I’d memorized the bass line and all the fills.

Mixing It Up

Often I’ll use a hybrid version of standard notation and the Nashville system, but it’s usually just for me. The reason for this is that I’ll write out any hooks, signature licks, or riffs that are important in standard notation, and keep the chord chart in numbers. I’ll also write any rhythmic hits or punches in standard notation above the numbers.

If I’m doing a gig with an artist that includes more than five songs, I sometimes will use cheat sheets so I don’t have to have the charts on a music stand. This makes you look much more pro to the artist and assures them that you have spent many days learning their material ... even though it may only be the night before!

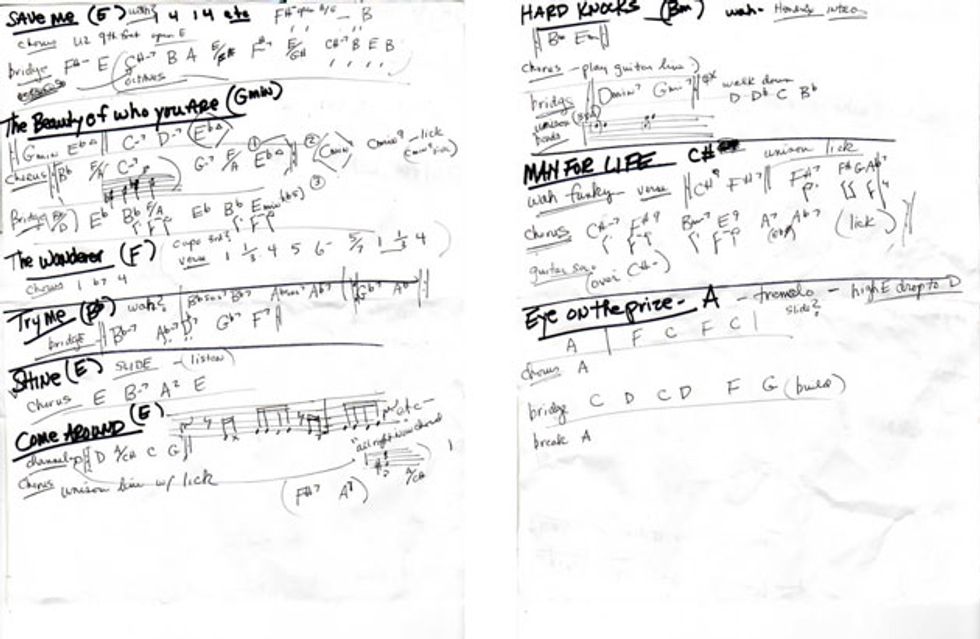

Ex. 6 is an excerpt of my cheat sheet for a gig I did with singer/songwriter Marc Broussard. I was able to cram 15 songs onto three pages.

You can see how I use the hybrid mish-mash version of the above methods. On “The Beauty of Who You Are,” I wrote the signature lick in standard notation so I would remember that, as well as the rhythmic hits in the chorus. That’s all I needed to get through the song. For “The Wanderer,” I relied on the Nashville system because when I use a capo on a guitar, it’s easier for me to read numbers—this is where the flexibility of the number system comes in. You could also use index cards for this method as well.

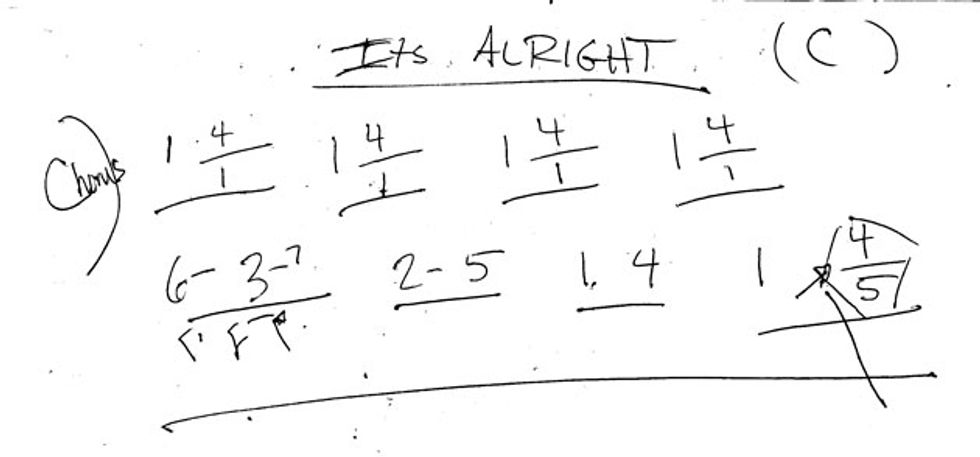

I used the chart in Ex. 7 for a gig I did with John Oates. It’s a quick-and-dirty arrangement of Curtis Mayfield’s “It’s Alright.” I wasn’t exactly sure what key John wanted to do it in, so I used numbers. In the key of C, it’s very easy to read. The rhythmic hits are an essential part of the song, so I wrote those in as well.

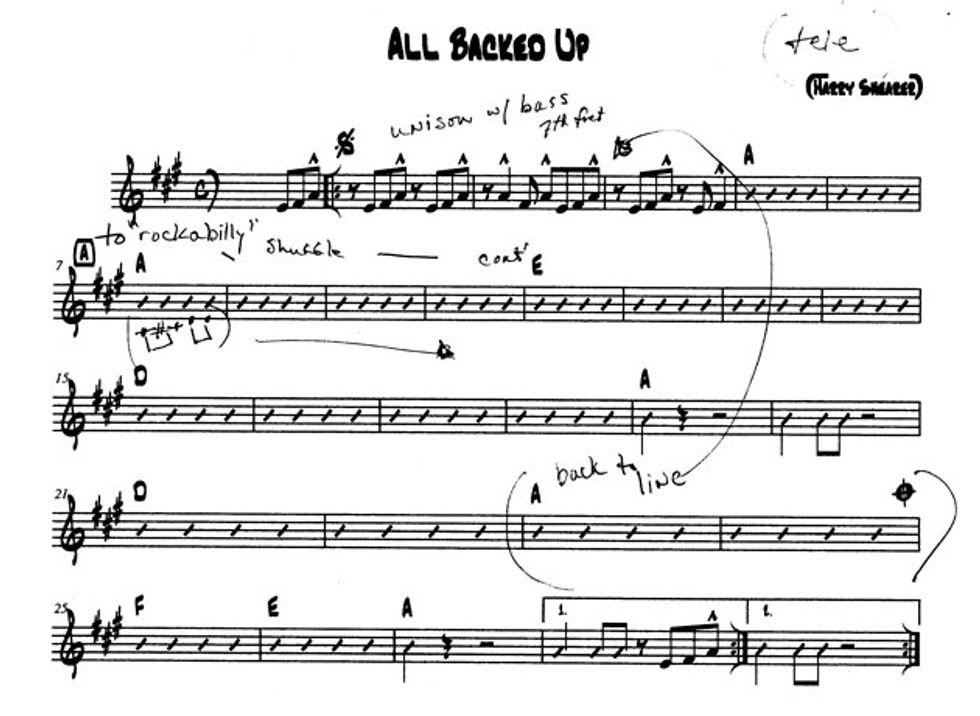

When there is an existing chart, I will quickly make my own notes and adjustments to fingerings. If the part is difficult to read on guitar, I may cheat and write some parts out quickly with tab. The chart in Ex. 8 was from a session I did with Harry Shearer, and it’s a very simple line that I doubled with bass. However, if I would have played it as written, it would have resulted in a very uninteresting guitar part. I abandoned the written line at the verse and went with a rockabilly part. Just writing out the tail end of the phrase was enough for me to know to go to the rhythm part on the verse. I’ve recreated the part so you can study the chart and follow along.

Sometimes you don’t have the luxury of being able to write out a chart, or you don’t want to use them on the gig. There are other ways to cram for a gig as well. Once, I was working with Boz Scaggs and I had one night to learn about eight songs with very specific guitar parts. I created a playlist in iTunes and put the songs with the guitar parts isolated on endless loop and just fell asleep listening to the parts. Sounds crazy, but it worked!

I hope some of these ideas and tips will be helpful to you should you find yourself in a time-sensitive situation. Just remember: There’s more than one way to get through it, and the bottom line is, whatever works for you is usually the best way.