For many guitarists who cut their teeth on blues, rock, or jazz, country guitar technique is a bit of a mystery—perhaps even a little intimidating. While country guitar has roots in the aforementioned styles, concepts such as open-string cascades, hybrid-picked double-stops, and pedal-steel bends can befuddle even the most accomplished players.

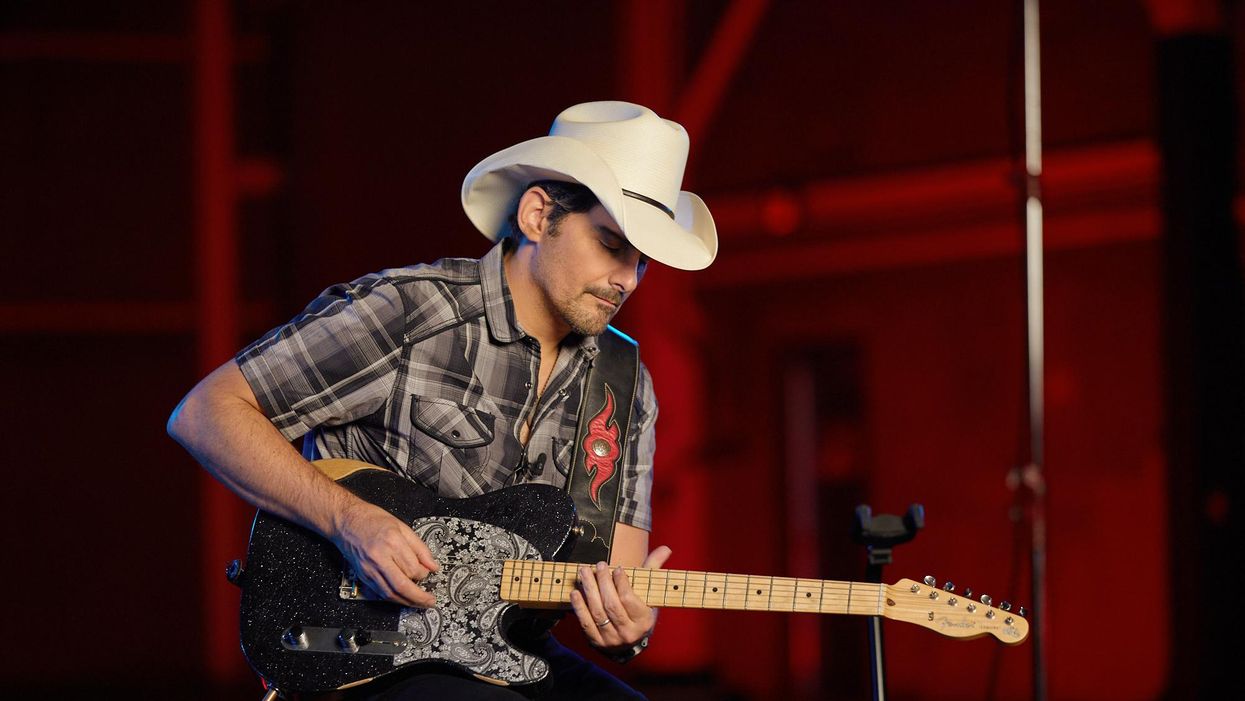

To help demystify country guitar, this lesson delves into a broad range of styles and techniques that have been popularized by guitarists over the past several decades—everything from bluegrass and Western swing licks to chicken pickin' passages and modern lead approaches. If you're new to country guitar, do yourself a favor and check out some of the more notable practitioners, past and present, including Merle Travis, Doc Watson, Chet Atkins, James Burton, Jerry Reed, Ray Flacke, Brent Mason, and Brad Paisley, to name just a few. Their inspiration, along with the examples in this lesson, will turn you into a genuine country picker!

Country Guitar Scales

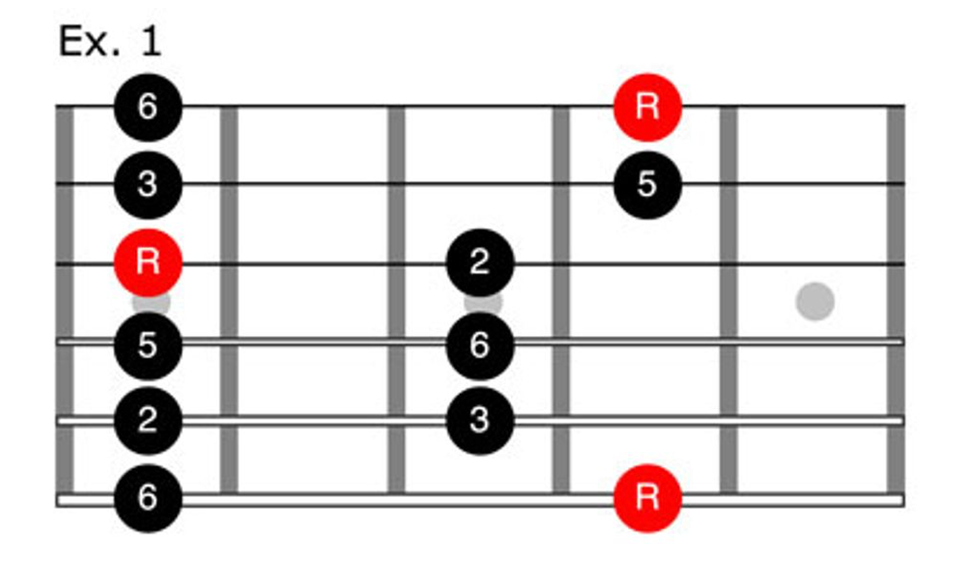

Despite the melodic complexity of their solos, country guitarists mostly rely on a few choice scales: major pentatonic, the blues scale, and the composite blues scale. The most prevalent of the three scales, major pentatonic, is a five-note scale (1–2–3–5–6) derived from the major scale (1–2–3–4–5–6–7). The scale's most common fingering is illustrated in Ex. 1, without regard to a specific key (use the root notes in red to help you relocate the scale to your key of choice).

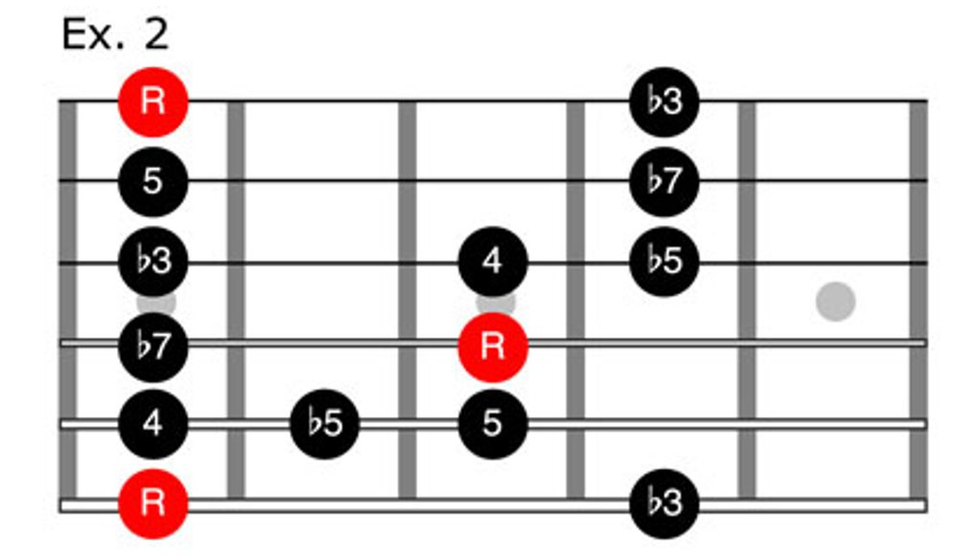

The blues scale (Ex. 2) is a variation of the minor pentatonic scale (1–b3–4–5–b7), in which the b5 is added to create a six-note scale: 1–b3–4–b5–5–b7.

Interestingly, parallel major and minor pentatonic scales—scales that share the same root—employ the same fingering, although the minor pentatonic pattern is located three frets higher. (Relative scales share the same notes, but have different tonics.) Consequently, the blues scale pattern differs from the minor pentatonic pattern by just one note—the b5.

The marriage of these two scales lets country guitarists blend major and minor tonalities over the major and dominant harmonies that permeate country music, particularly the juxtaposition of major (3) and minor (b3) notes, which is a staple of the genre.

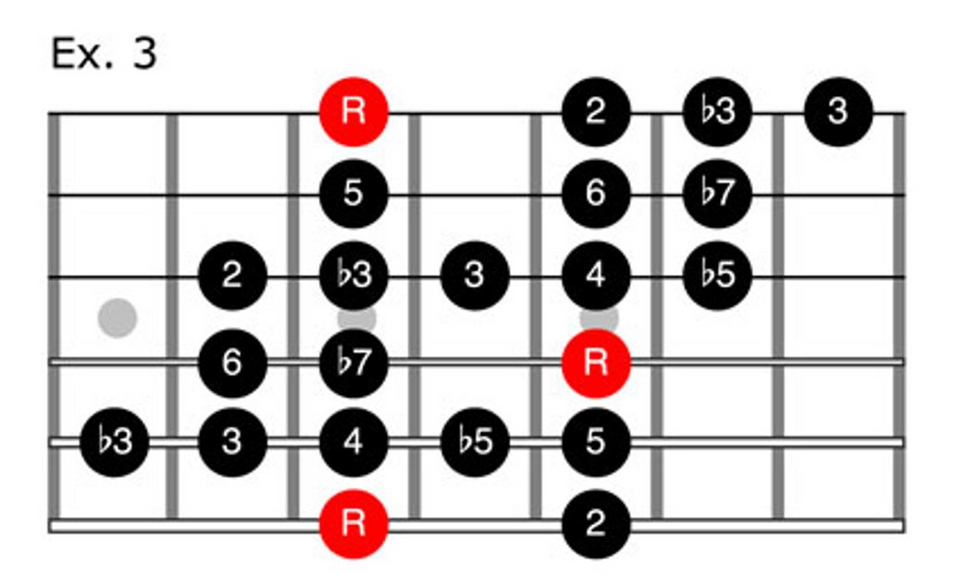

Ex. 3 shows a fingering for the nine-note composite blues scale (1–2–b3–3–4–b5–5–6–b7). Guitar players rarely—if ever—incorporate every note of the composite blues scale into a single phrase. Instead, they pick their tones judiciously, depending on the sound and feeling they want to communicate at a given moment.

The Composite Blues Scale

Country Guitar Phrasing

Country phrasing can be summarized in two words: chord tones. While chord-tone soloing is found in all forms of music, perhaps no genre epitomizes the concept more than country. Unlike lead-guitar styles that focus on the overall sounds that certain scales impart or the technical skills required to play them, country lead is, first and foremost, based on targeting chord tones on the downbeats—a direct influence of bluegrass.

The following example in Ex. 4 is an open-position bluegrass lick played over a V7–IV–I (G7–F–C) turnaround progression in the key of C. Note the presence of chord tones on nearly every downbeat (indicated between staves), as well as the bluesy maneuvers at the ends of measures two and three.

Ex. 4

Targeting chord tones isn't the only trick to replicating country phrasing. Another key element is the way hammer-ons and pull-offs are implemented. Ex. 5 is a four-measure phrase that outlines an A major harmony with notes from the A composite blues scale (A–B–C–C#–D–Eb–E–F#–G). Note that, when three notes are voiced consecutively on a string, a single hammer-on or pull-off is used—an approach favored by rock and blues guitarists.

Ex. 5

Ex. 6 is a "countrified" version of the same phrase (note the chicken pickin'). On beat one of the first two measures, the pull-offs connect just the second and third notes, rather than all three. This approach places greater emphasis on the notes on beat two—A and E, respectively—both of which are chord tones, whereas the three-note pull-offs emphasize all three notes equally. The same concept is applied in measure three, where the third-string notes—B, C, and C#—are broken up with a hammer-on from the b3 (C) to the 3 (C#), which is located squarely on the downbeat of beat three. Remember, this phrase is played with hybrid picking, so use your flatpick for the notes with the downstroke symbol and your middle finger (m) for the others.

Ex. 6

Single-Note Lines

Before diving into some of country guitar's more advanced techniques, let's start with a few single-note concepts. Ex. 7 is perhaps the most ubiquitous guitar lick in all of country music, particularly in bluegrass. Referred to as the "G run," or "Flatt run" (named after bluegrass legend Lester Flatt), the lick is commonly used as an ending phrase to signal the end of a solo or chorus. The phrase itself is rooted in the G major pentatonic scale (G–A–B–D–E), with the addition of the b3 (Bb).

Ex. 7

Ex. 8 is a descending bluegrass lick that's rooted in the G composite blues scale (G–A–Bb–B–C–Db–D–E–F) and can be played over major or dominant harmonies. Like Ex. 4, chord tones are present on most of the downbeats, with a cool chromatic passage (D–Db–C) appearing on beats three and four of the first measure. And don't miss the b3-to-3 (Bb-B) minor-major "rub" that crosses the barline, or the variation on the Flatt run at the end of the phrase.

Ex. 8

Bass-string licks are also an essential element of country lead playing, as they pack considerable punch when played through a Tele with a clean tone. This next phrase in Ex. 9 is relegated to the guitar's bottom three strings and incorporates eight of the nine pitches of the E composite blues scale (E–F#–G–G#–A–Bb–B–C#–D).

Ex. 9

Western swing is an up-tempo, jazz-influenced form of country music that originated in the Western and Southwestern regions of the United States in the '30s and '40s. This swing lick (Ex. 10) is rooted in the extended form of the A composite blues scale and moves incrementally from the 10th to the 5th position. Despite the chromaticism, well-placed chord tones (downbeats!) effectively outline the A7 harmony. Don't forget to swing those eighth-notes!

Ex. 10

Chicken Pickin'

Although the term has become a bit clichéd, chicken pickin' is an essential component of country guitar. Chicken pickin' is a technique that encompasses both a picking approach (i.e., hybrid picking), as well as the sound that results from blending fretted and muted pitches, which is akin to a clucking chicken.

Ex. 11 combines 4th-string mutes with staccato notes on the 2nd string. The minor-sixth shapes are derived from fully fretted versions of an open C chord (G and F, respectively), and articulated with a combination of the pick (4th string) and middle finger (2nd string). The muting can be applied with your picking-hand palm, your fretting-hand fingers, and/or the middle finger of your picking hand (while plucking with the pick).

Ex. 11

This next example (Ex. 12) involves double-stops and muted "ghost notes" to outline the G–C–G (I–IV–I) progression. The double-stops are derived from various major triad, major 6, dominant 7, and dominant 9 voicings, and should be plucked with a combination of your middle and ring fingers. Meanwhile, articulate the ghost notes exclusively with your pick.

Ex. 12

Country Guitar Bends

Ex. 13 combines chicken pickin' and a robust oblique bend to mimic the steel guitar. Mute the final pickup note with the index finger of your fretting hand, whereas the pre-bends should be muted with the palm of your picking hand.

Ex. 13

Open-String Cascades

Dissonance is frowned upon in some music—but not so in country! In fact, one of the key elements of country guitar is the fleeting dissonance created by blending fretted pitches and open strings, particularly when it results in small intervals such as minor seconds, major seconds, and minor thirds. These open-string "cascades" can be performed in both ascending and descending order, each of which is presented here.

In Ex. 14, minor-third shapes are paired with open strings to outline the E major harmony. Pick the three-note groupings with a down-down-up sequence, shifting the shape up two frets on beat four of measure one. Melodically, the notes yield a colorful combination of both major and minor tonalities.

Ex. 14

A variation on the previous example, Ex. 15 combines major- and minor-third shapes and open strings to outline the A major harmony. Pay close attention to the fingerings (indicated below the staff) as you play this one. Once you get it under your fingers, shift the pattern down two frets to convert it to a G major lick.

Ex. 15

Descending cascades require a different approach from the ascending versions. For this, attack all fretted pitches with the flatpick and open strings with the middle finger. Allow the latter to ring out clearly as you move down the neck.

Ex. 16 is a scalar line that outlines the G7 harmony with pitches from the G Mixolydian mode (G–A–B–C–D–E–F), with the one exception being the b3—Bb—that appears on beat three of measure two.

Ex. 16

Double-Stops

A cornerstone of country guitar, double-stops come in many forms, one of which you experienced in Ex. 12. In this section, double-stops are presented in two categories: diatonic and chromatic. Diatonic phrases are composed entirely of pitches from the same key or scale, whereas chromatic phrases contain diatonic and non-diatonic pitches alike.

The diatonic phrase in Ex. 18 is a variation on Ex. 12, except the double-stops are voiced exclusively on strings 3 and 4, the ghost notes are fully fretted (rather than played as mutes), and the harmony is a static G major chord.

Ex. 18

Ex. 19 alternates chromatic (half-step) double-stop slides with iterations of the open A string. The slides target pitches of a 4th-position A7 voicing before moving on to a common A major triad shape at the end of measure one. The double-stops are plucked with the middle and ring fingers, while the open A string is handled exclusively by the pick.

Ex. 19

Pedal-Steel Bends

Like double-stops, pedal-steel bends come in many forms, but the purpose of the bends is singular—to mimic the pedal-steel guitar. In this section, pedal-steel bends are presented in three contexts: a single-note phrase, a double-stop phrase, and a triple-stop phrase.

Ex. 20 is a single-note phrase that outlines a V–IV–I (A–G–D) turnaround progression in the key of D. Push each bend upward exactly a whole-step (precision is crucial) and hold them while articulating the stationary pitches on the top two strings. For the half-step bend in measure four, nudge the 5th string upward a half-step while holding down the D note at the 7th fret on the 3rd string.

Ex. 20

Ex. 21 outlines the C7 harmony (C–E–G–Bb) with double-stops consisting exclusively of chord tones. The initial double-stops contain the notes C and E (root and 3), followed by G-Bb (5-b7), E-G (3-5), and C-E (root-3), respectively. Use your fourth finger to fret the top notes and your second finger (reinforced with your first finger) for the bottom notes.

Ex. 21

This final pedal-steel phrase (Ex. 22) is a chord-based passage that, like Ex. 20, outlines an A–G–D turnaround progression. Measures one and two feature a common triad shape that is manipulated with a 3rd-string whole-step bend, briefly implying major 6 chords (A6 and G6, respectively). Be sure to keep the notes on the top two strings stationary as you bend the 3rd string with your index finger. In measure three, a variation on a common D barre-chord shape implies the I chord. Let all three notes ring together, and bend the 3rd string down towards the floor so as not to interfere with fretted pitches.

Ex. 22

Country Rhythm Guitar

Because country rhythm guitar is a topic worthy of an entire book, this lesson will limit its focus to a few concepts that have been a staple of the genre for decades, particularly in its more traditional styles.

Ex. 23 is the classic "boom-chicka" strumming pattern in which alternating bass notes (the "boom") are played on beats one and three of each measure, followed on beats two and four by eighth-note chord strums (the "chicka"). Here, the I and V chords (C and G) are voiced in open position, while the IV chord (F) is a common 6th-string barre-chord shape.

Ex. 23

For fingerstylists, no technique is more indispensable than "Travis picking." Named after country legend Merle Travis, this fingerpicking concept involves plucking steady, alternating (generally, root–5 or root–3) quarter-notes on the bass strings with the thumb (or pick), while the remaining fingers pluck chord tones on the treble strings.

Ex. 24 contains a series of one-measure exercises to get you acclimated to Travis picking. After starting solely with bass notes, the patterns become progressively more complex. Once you're comfortable with the exercises, move on to Ex. 25, which features a variation on the patterns from Ex. 24, including melodic movement on the treble strings.

Ex. 24

Ex. 25

Ex. 26 is a rhythm-guitar concept similar to the riff featured in Merle Haggard's 1969 hit "Workin' Man Blues." The song has since become a country standard and is the vehicle for many Nashville jam sessions. The riff itself is a variation of the one Scotty Moore played in Elvis Presley's rockabilly classic, "Mystery Train."

The pattern is presented here in two-bar segments, illustrating how it can be altered to accommodate the I7, IV7, and V7 chords (A7, D7, and E7) of a 12-bar blues in A. The double-stop pattern on strings 3 and 4 is consistent throughout, while the roots vary between open strings (A7 and E7) and a thumb-fretted 6th-string note (D7).

Ex. 26

This article was last updated on June 3rd, 2021.