Pardon me while I beat this dead horse: Guitarists are often hobbled by muscle-memory patterns. At times our musical choices aren’t choices at all—they’re just our hands operating on auto-pilot.

Sometimes smashing the muscle-memory box means exploring unfamiliar notes and scales. But it can also be about playing the same old notes and scales using new melodic patterns and note combinations. That’s our mission this month. We’re going to mutate familiar blues scale patterns into unrecognizable shapes via angular melodic choices and jagged dissonance. This isn’t about playing blues—it’s about wringing new ideas out of old ones.

Compare Ex. 1 and Ex. 2. The first example consists of a few numbingly conventional licks. The second one is a noisy racket, full of near-painful dissonance. But what do the two examples have in common?

The two attitudes are galaxies apart. Still, the rhythms are identical on both clips. And believe it or not, so are the notes. Granted, those notes don’t appear in the same order. But both examples borrow from the same pool of pitches.

Choose Your Own Adventure

Now, I’m not saying that Ex. 2 is “better” than Ex. 1, or that guitarists who play licks like Ex. 1 suck. Nor am I suggesting that Ex. 2 is well-suited to blues music. If you whip out these licks at the ol’ Tuesday night blues jam, they’ll probably move it to Wednesday and not tell you. This is simply about stretching your vocabulary by stretching your fingers.

Here’s one of those stretches, and a challenging one at that. Chances are the scale in Ex. 3 feels very familiar. It’s the old blues-box pattern many of us learned soon after we started on guitar.

Click here for Ex. 3

But what if, instead of playing the scale straight up and down, we juggle the note order a bit? Try Ex. 4.

Click here for Ex. 4

Ex. 4 is way harder to play. It sounds weird because we so rarely hear the scale in that configuration. Here the melodic intervals are mostly fourths (except for the major third between C and E). That means playing many consecutive notes on the same fret, but on different strings, using the same finger. It’s even tougher when you play the scale legato, with minimum possible gap between notes. (This problem is unique to guitar and bass. For most instruments, playing fourths is no more difficult than playing thirds.)

Venturing Fourth

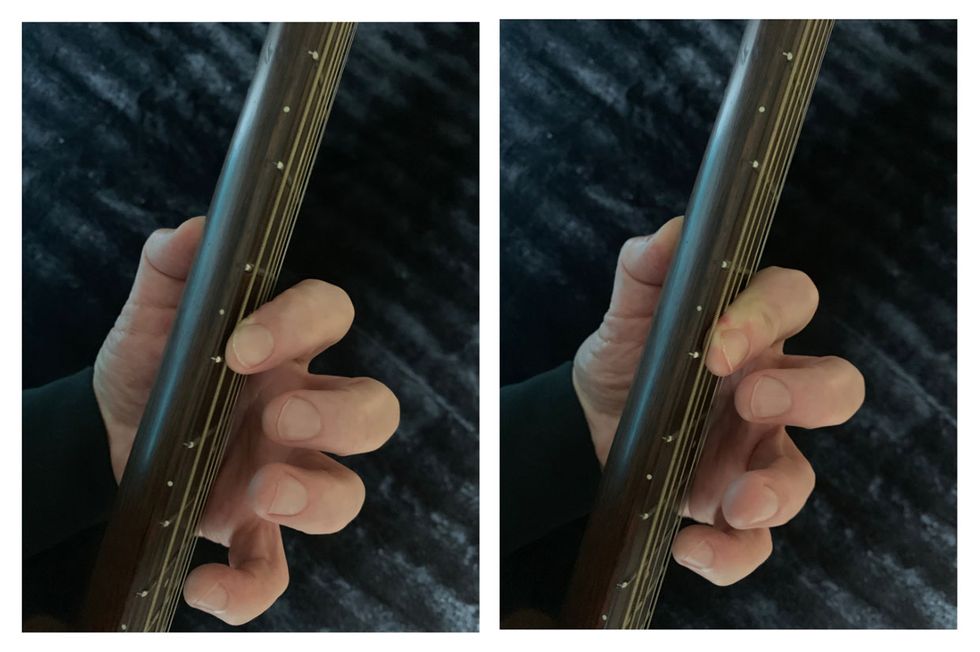

My long-ago guitar teacher, Ted Greene, taught me to play ascending fourths by fretting the lower note with a fingertip, like you normally would. But instead of lifting the finger to play the note on the adjacent string, you flatten the finger, bending your first knuckle slightly and pressing the note with the flesh between fingertip and first knuckle (Photo 1). It helps to be a bit double-jointed.

Photo 1

Anyway, Ex. 4 is a bitch. But practicing it for a few hours will disrupt your muscle-memory habits and lead you to new melodic ideas.

Seventh Heaven—or Hell?

Minor sevenths are more dissonant—and less common melodically. But playing them is a lot like playing fourths, except that the notes don’t fall on adjacent strings. In Ex. 5, all the intervals are minor sevenths, except for the major sixths between C and A. Try the same finger-flattening technique as in Ex. 4. You’ll just be fretting the higher note closer to the finger’s first knuckle.

Click here for Ex. 5

Complications Ensue

The term “blues scale” means different things to different people. For some it’s the pattern in Ex. 3. Others would insist that this should be called a minor pentatonic scale, and that it’s only a blues scale if you add the b5, as in Ex. 6.

Click here for Ex. 6

I say, blues scale, schmooze scale. Great blues players might use every note in the chromatic scale. If you combine the notes in Ex. 6 with the arpeggios of the major I, IV, and V chords, that’s 11 of the 12 notes in the chromatic scale—everything but the b2. Which you can also use, as discussed in a recent column. Plus, there are all the pitches that fall between scale steps when you bend strings or play with a slide.

But for now, let’s hear what happens when we apply those uncomfortable intervals to the scale in Ex. 6. Ex. 7 uses the same notes, but with the skip-a-string approach of Ex. 5. With the b5 mixed in, things get real dissonant, real fast.

Click here for Ex. 7

The added b5 introduces major seventh intervals alongside the major sixths and minor sevenths. It gets even crunchier when you play the same notes as harmonic intervals (Ex. 8).

Click here for Ex. 8

Now let’s return to where we started. Here’s Ex 1 again, now with notation and tab. As you can see, it’s a mix of blues-box notes and major-key chord tones.

Click here for Ex. 1

Again, Ex. 2 employs the same rhythms and palette of notes as Ex. 1, but with provocative harmonies and jagged melodies. If there really were such a thing as a bruise scale, this might be it.

Click here for Ex. 2

The moral: Sometimes the difference between playing inside and playing outside is simply a matter of approaching familiar material from an unfamiliar angle.