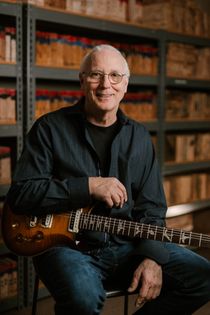

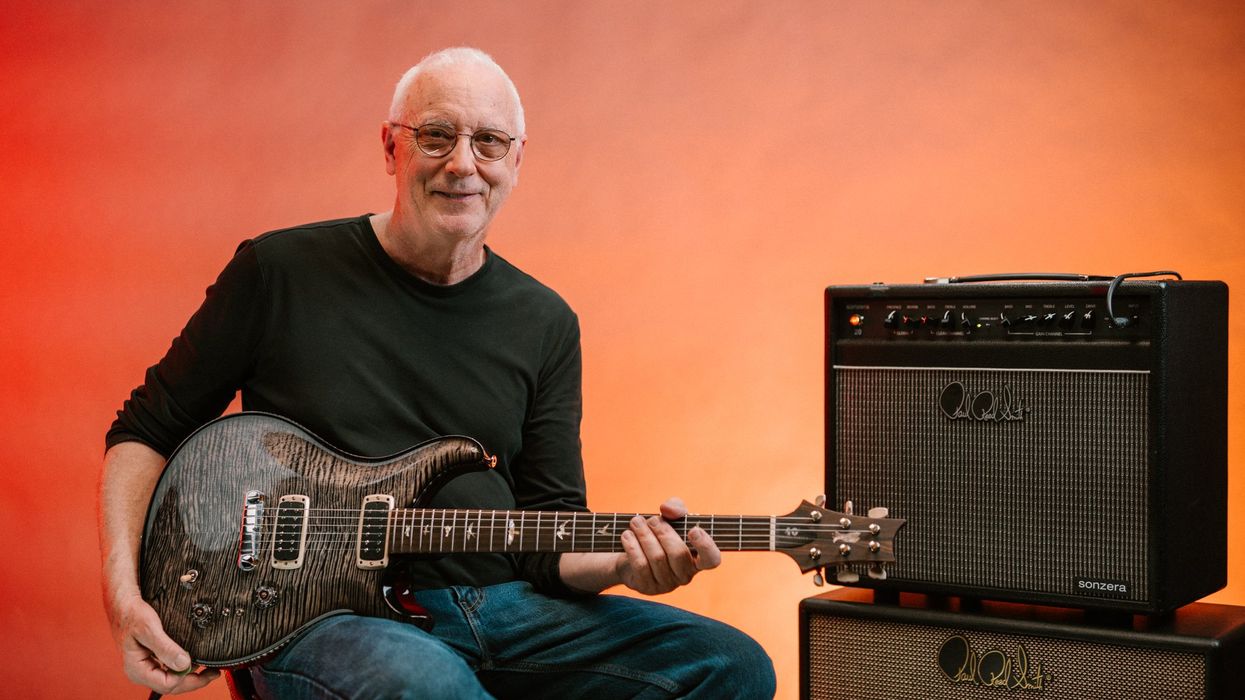

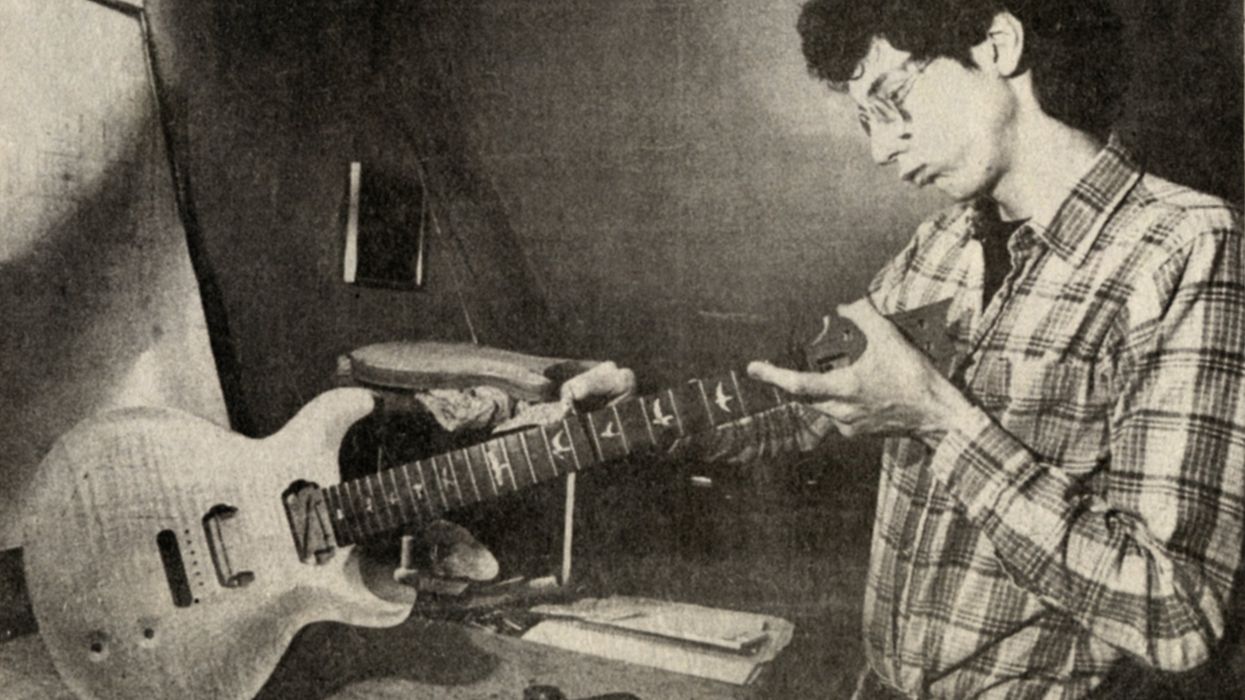

I am a student of Ted McCarty, Leo Fender, and the guitar industry as a whole. I simultaneously started as a guitar maker and guitar repairman. Repairing guitars is an unbelievable way to learn how to design an instrument that repair people and road techs won’t struggle with, because you get to see firsthand all the ways the guitars on your bench failed. From my beginning, I was able to design out of PRS guitars any of the recurring problems I saw come across my repair bench (which is not to say we’ve never made a mistake of our own). Those early repair experiences taught me that sometimes some of the greatest lessons come from the mistakes of past guitar manufacturing.

Let me give you an example. In the late 1960s to mid ’70s, there was a guitar company in Maryland called Micro-Frets. They were best known for a nut that made each string’s height and length adjustable. One of the mistakes they made was that one of the high frets was badly in the wrong position, so when you looked at the neck, you could see that two frets were too close together and the next two frets were too far apart. I’ve always believed that the frets on an electric guitar should be in the right places within a few thousandths of an inch and the nut should be moved so the guitar plays in tune in first position. While the Micro-Frets guitar fixed one problem, it was impossible to play a high chord on that instrument because the fret positions were not movable. It reinforced my determination that the frets need to be in exactly the right locations. This was the inspiration for some of our patents.

Here is a list of general mistakes that guitar makers have made in the past that I believe should not be repeated:

• Many brands never glue(d) the frets in. Many times in my repair shop, frets would lift up out of the fretboard so much that the high E string would get caught under the edge of the frets. Also, in my opinion as a guitar repairman, if you don’t glue the frets in and you have a sweaty night playing guitar, the frets will change their heights and necessitate a fret level.

• Many guitar makers don’t glue the nut on well or at all. In my experience, you want solid contact here, as the nut is one of the few spots (besides the bridge and tuning pegs) that the strings are making contact with the rest of the guitar.

• Many guitar companies make nuts out of PVC. To me, this is not a good idea, because it negatively affects the tone and wear factor of the guitar. Bone nuts historically are the industry standard for high-end instruments.

• Many instruments with Floyd Rose nuts cannot have a truss rod adjustment made without taking the nut off. In addition, there are lots of guitars where you can’t adjust the truss rod without taking the pickguard off. In my mind, that’s poor design.

“I’ve learned as much from the mistakes that have been made as from the unbelievably graceful positives that have been developed.”

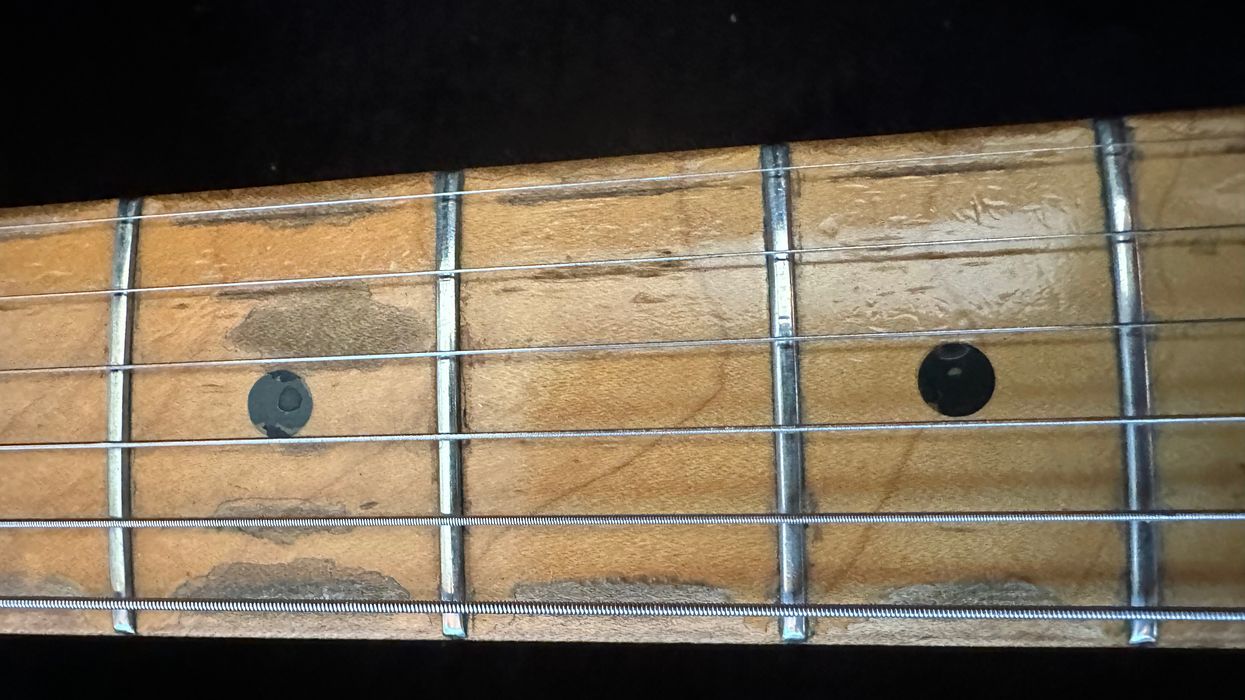

• Many manufacturers are not drying their woods nearly enough. The reason frets stick out of the side of a neck after the first winter on some instruments is because the manufacturer did not dry the fretboard sufficiently. It shrank side-to-side and the frets did not. As a point of reference, I have never seen a Fender or Gibson guitar made before 1965 that had this problem. I interviewed Ted McCarty, and he said they were baking the fretboards at Gibson in the early ’50s. The fact that this problem is so commonplace in our industry right now is not okay.

• Finish matters, and not just the material but how much you use, how it dries, etc. At one point, in the very late ’60s through the ’80s, Fender was putting so much polyester on the maple necks as a finish that you could barely get to the frets to level them because the finish filled up all the space between the frets. On this one, you gotta be kidding me.

• Again, when I was interviewing Ted McCarty about the sideways Vibrola on early ’60s SGs, he told me that the artists were telling him they wanted the vibrato motion to be the same motion they used when strumming the guitar. His exact quote was: “That was a mistake.” In practical terms, the sideways Vibrola is not considered a holy grail vibrato for sound or feel.

To this day, I believe I’ve learned as much from the mistakes that have been made as from the unbelievably graceful positives that have been developed while creating our entire guitar-playing and electric-guitar-making industry. Paying attention to the mistakes—and great successes—of the past helps guitar players and guitar makers know why some instruments are given “permission from the market” and some are not. The truth is, some instruments are better at making music than others. That’s part of learning, in my mind. You can apply learning from mistakes to pretty much any area of life, by the way—not just guitar making.