It’s a long way to the top if you want to rock ’n’ roll—or so the saying goes. On the surface, that sounds like a blunt, self-evident truth. But the longer I think about it, the more I suspect it’s not just incomplete, but misleading. That idea—that there is a clearly defined “top,” and that reaching it is the point—has quietly infected far more than music. It colors how we measure success in almost everything we do.

In sports or business, the metrics are tidy. You win or you lose. You’re ranked, valued, traded, promoted, or cut. The scoreboard doesn’t lie, even when it’s cruel. But music isn’t a ladder, and it isn’t a tournament. So why do we keep pretending it should be judged like one? Does being a musician really require a podium?

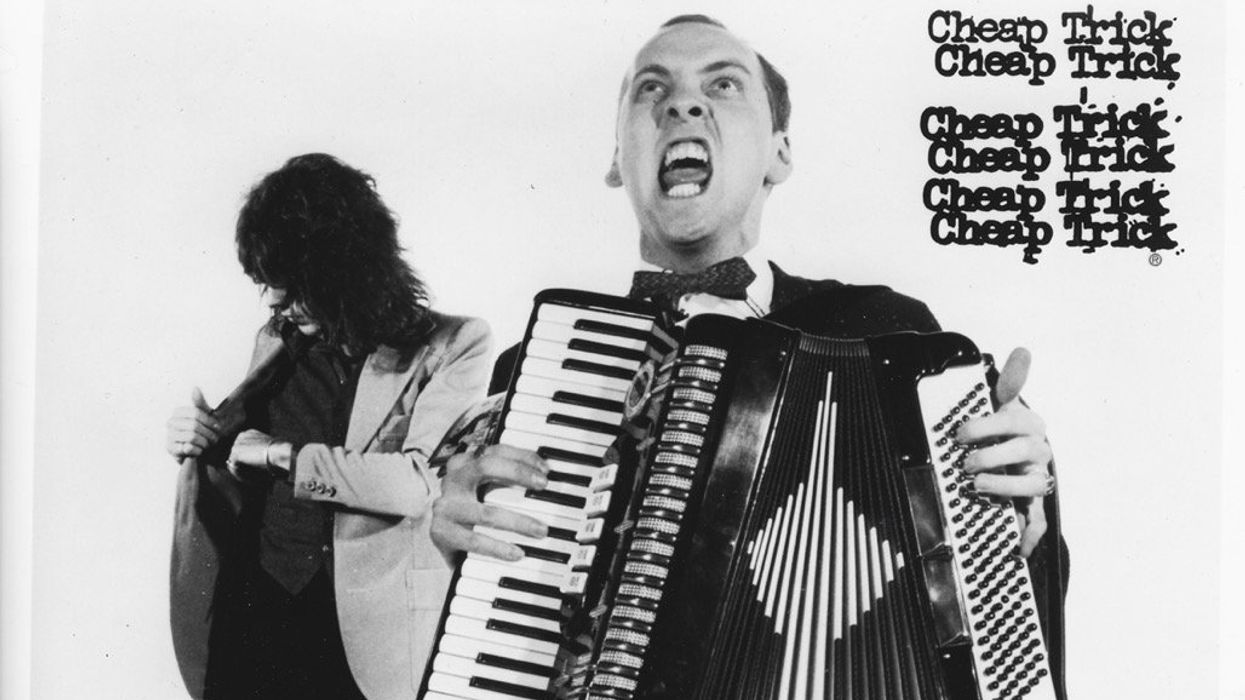

Most of us will never be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, and I doubt that possibility crosses anyone’s mind when they first pick up an instrument. That kind of recognition might be a pleasant side effect of a life in music, but making it the goal feels like the opposite of what art is meant to be. History bears this out.

“Playing in a band is inherently collaborative, cognitively demanding, and demonstrably good for your brain.”

Consider the Beatles—arguably the most successful and influential band in popular music. They didn’t set out to conquer the world. They wanted to write songs, make records, and play shows. Early on, they joked about reaching the “topper-most of the popper-most,” a phrase that sounded aspirational but probably felt abstract at the time. In practice, that ambition looked like four musicians—and their roadie, Neil Aspinall—crammed into a cold, smelly van, hauling gear through grim northern English towns, grinding out one-night stands. But that was the life of a rock ’n’ roll musician.

Which raises an interesting question: What does “the top” mean for the rest of us? An album credit? A few good club gigs? A song that lands with someone at the right moment? Music has never guaranteed financial success, and our education system seems to understand that all too well. As schools increasingly resemble business pipelines, music programs struggle for survival while sports budgets grow practically unchecked.

I’ve watched from the sidelines as stick-and-ball sports have exploded in K-12 education. Competitive athletics have existed in schools for more than a century, originally emerging from physical-education programs designed to improve general fitness—especially after World War I exposed how unprepared many young Americans were. But sports weren’t always industrialized the way they are now. Today, despite near-lottery odds of making a living as an athlete, parents and institutions often behave as if success is just a scholarship or draft pick away.

The incentives are revealing. DePaul University can lay off more than a hundred employees while planning a $42 million sports center, justified as a student recruitment tool. Team building and collaboration are the stated virtues, but let’s be honest—we worship individual stars. Music, meanwhile, is treated like a luxury.

That’s odd, because music delivers many of the same benefits, without the head injuries. Anyone who has stood in a crowd at a concert knows the tribal electricity is no different from a packed sports stadium, except everyone goes home a winner. Playing in a band is inherently collaborative, cognitively demanding, and demonstrably good for your brain. Yet music education is often marginalized or eliminated entirely. I’m not suggesting everyone should become a musician, but teaching respect for art, and how to listen to it, is valuable for everyone.

For more than half a century, musicians have driven fashion, shaped advertising, defined film soundtracks, and filled the spaces we inhabit—from cars to elevators to restaurants. You can escape sports coverage if you want to, but you can’t escape music. It sets an emotional tone, reflects social mood, and quietly binds communities together. Playing music isn’t decorative; it’s functional, social, and deeply human.

Twenty-five years after those freezing van rides, two of the three surviving Beatles stood onstage in 1998 as the band was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, then only in its third annual ceremony. I’m guessing it wasn’t as much fun as a real gig. Watching artists of that stature squirm through acceptance speeches suggests the honor itself was never the destination. Music was.

That’s the thing: when you’re infected with the boogie-woogie, the reward isn’t a trophy—it’s the playing. In that sense, we’re already in the Hall. If we share the joy, value the process, and savor every note we play or hear, maybe it turns out it isn’t such a long way to the top after all.