In 2008, Malcolm Gladwell's book Outliers: The Story of Success debuted at No. 1 on The New York Times Best Seller list, clinging to that coveted slot for 11 consecutive weeks. If you were unlucky enough to be the child of a Tiger Mom during this time, you probably wasted 20 torturous hours every week practicing piano or violin. Today you're a disillusioned 12-year-old with no friends, limited social skills, and a deep-seated hatred for music. You probably spend the majority of your non-school time locked in your bedroom playing Call of Duty: Black Ops, while devouring cheese puffs and swilling room-temperature Mountain Dew. Thank you, Outliers, for ruining thousands of childhoods.

Gladwell bases much of his ill-conceived Outliers on the “10,000-Hour Rule" (borrowed largely from the work of Swedish psychologist Anders Ericsson). The rule, as you probably guessed, asserts that to master a given skill, you need to invest 10,000 hours of deliberate practice. Gladwell gives The Beatles as a prime example, and suggests that their incredible success could only have happened after they performed more than “1,200 gigs between 1960 and 1964" while in Hamburg, Germany. Gladwell ignores the fact that there were probably 100 bands in Europe working this same circuit of clubs, playing the same grueling schedule. If the “10,000-Hour Rule" were true, there would have been many bands equally as good as the Fab Four. Also, remember that Pete Best was the drummer for all of these gigs. It's hard to say why Pete got the sack, but George Martin claims that Best was not the best when it came to meter, so all of this practice did not make Best a master.

Like most oversimplifications, Gladwell's theory has elements of truth, but ultimately remains a lie. If it were as simple as putting in the time, most of us would be virtuosos. But honestly, I could practice for 20,000 hours and still not play as well as Tommy Emmanuel. Players like that are touched by the hand of God—or innately gifted, for you atheists out there. Granted, Tommy plays all the time and this constant playing helps him perform at his best, but what he does as an artist goes well beyond technical proficiency.

I'm a big fan of Carol Kaye, the famed bassist from the Wrecking Crew. In an interview she described a session early in her career where the leader said she'd been rushing on a track. She didn't believe it until she heard the playback. Once she was convinced she had meter issues, she went home and practiced for three days with a metronome. After that, Kaye recalled, “I had it."

is a cute little pop ditty.

Three days? I've spent 20 years practicing with a metronome and, truth be told, sometimes I'm on it, sometimes I'm not. Carol Kaye did not need 10,000 hours to master her instrument and—apparently—I need a whole lot more.

Does mastery really matter when it comes to art?

Since Gladwell brought it up, let's look at The Beatles again. This may sound like heresy to some, but The Beatles' early work just isn't that interesting. On their first two albums, Please Please Me and Meet the Beatles!, there's a 3 to 4 ratio of covers to originals. These albums contain some great songwriting, but these Beatle songs sound a bit formulaic compared to their later work. You can hear the influence of the covers they'd been slogging through during their club days.

Their music grew much more compelling when they quit playing so much and instead took time to think, experiment, and explore where music could go. Compare “All My Loving" to “A Day in the Life." The voices sound comparable, but that's where the similarities end. “A Day in the Life" is a great work of art; “All My Loving" is a cute little pop ditty. The Beatles were great because fate or good luck brought these four immensely talented kids together. Their chemistry just worked and they encouraged each other to become great musicians.

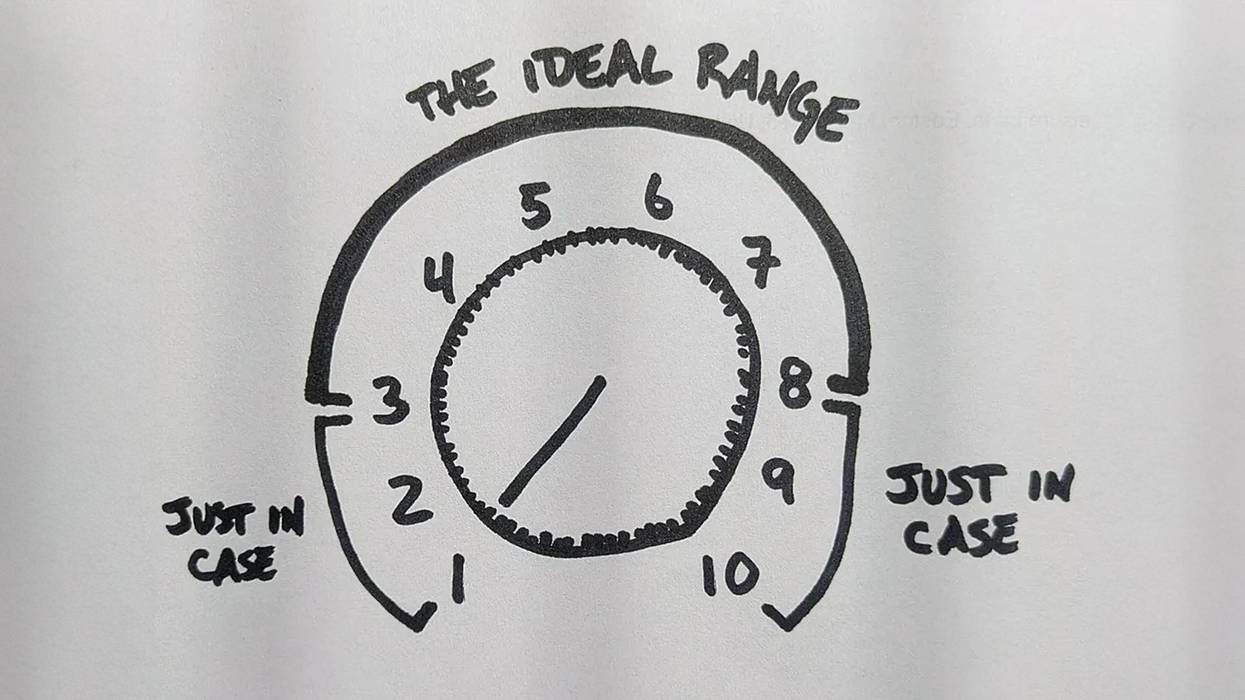

So for all you lazy musicians out there, here's a reason to rejoice: Practicing can hurt your playing. If you spend 10,000 hours playing with a bad drummer or relying on your own faulty meter rather than using a reference like a metronome, you will probably become a worse player, not a better player. If you practice the same patterns for hours and hours (scales, riffs, or whatever), your fingers will automatically repeat these patterns every time you pick up a guitar. You'll be able to execute these bits well, but who cares? It's going to be boring for you and your audience. Like Charlie Parker said, “Master your instrument, master the music, and then forget all that bullshit and just play."

You have to put in the hours to improve your playing, but excessive practice does not guarantee greatness. In fact, it can stifle creativity or reinforce bad habits. There's no telling how many hours I've put into music ... 30,000? 40,000? I've made some improvement and I've reinforced some bad habits. I've gained dexterity and had some carpal tunnel issues. I've improved my ear training and suffered some hearing loss. Sometimes I play well, sometimes I sound like I'm playing guitar with my toes. It's said “practice makes perfect," but we also say “nobody's perfect." I say “pobody's nerfect," so let's give ourselves a break.