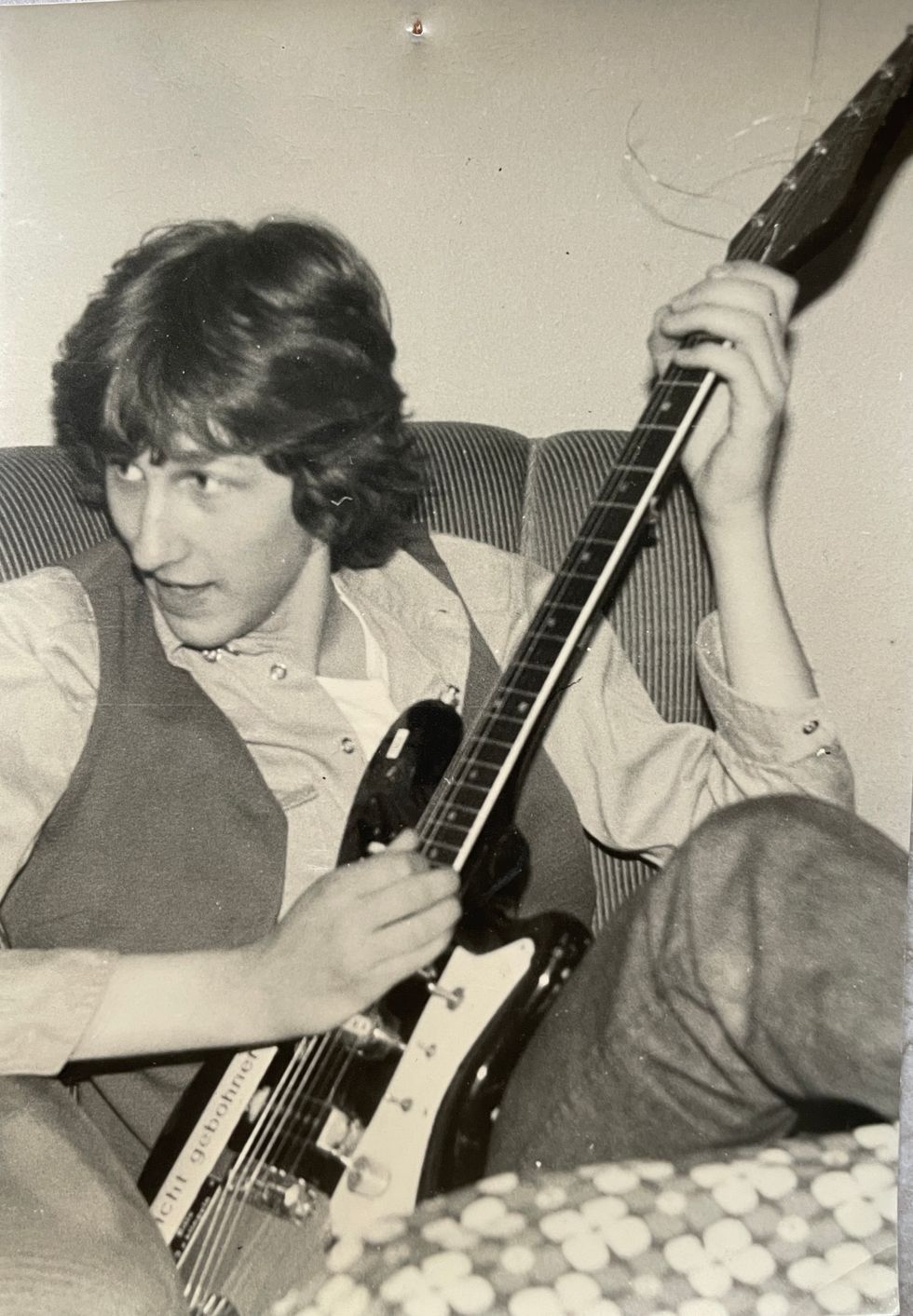

My favorite amp's place in my heart has more to do with nostalgia than tone. My parents bought me a 1964 Vibroverb when I was 15, for $125, from Hansen Music in Billings, Montana. Its tolex was scarred with cigarettes burns, and it had a permanent smell of burning wires. I bonded with this amp over longs hours sitting cross-legged on the floor of my childhood room, lights off, staring at the glowing tubes in back while I learned how to play.

The first time I understood what tone meant, I was playing that amp. I had just graduated high school and had hooked up with a band playing four sets per night, five nights per week. One night the band's other guitar player handed me a left-handed cigarette on the break. When I came back inside, I turned all knobs right and became a proton vibrating on the edge of the voice coil of that Jensen C15N speaker. When I hit a low E, I connected to every molecule in the universe and suddenly understood the divine power of superior tone. I spent most of the night just hitting that low E and letting it ring. Not a great performance, but a memorable experience, all thanks to that amp (and perhaps, the devil's lettuce).

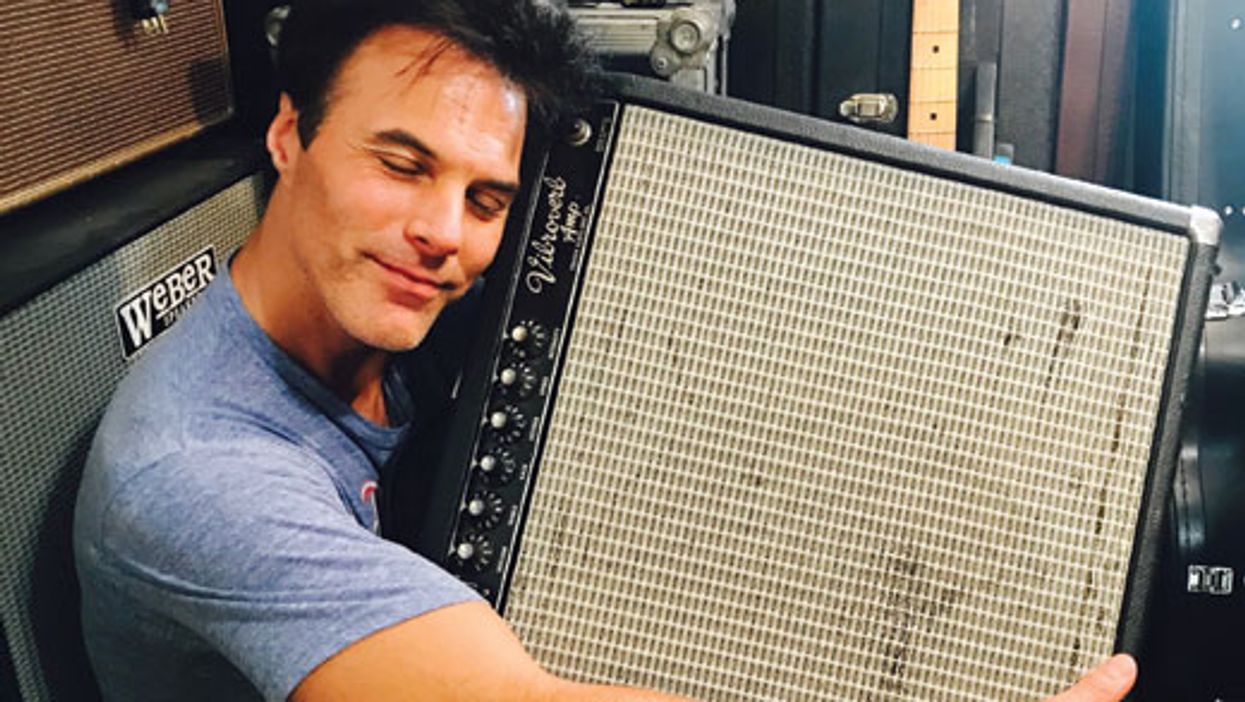

Eventually the amp grew old, cranky, and unreliable. In a move of shuddering stupidity, I traded it for a Peavey bass head for my then-wife. I kicked myself for 25 years, then spent way too much money buying another 1964 Vibroverb.

Vibroverb No. 2 sounded like, well … number two. It didn't take pedals well and lacked definition. I wanted to love it, but every time I turned it on I felt secretly disappointed. By chance, I met Don Thomas of Wathen Audiophile. Don suggested that my amp's lack of luster might be fixed with better tubes.

Back when I owned my first Vibroverb, tubes were plentiful and, in general, made from better materials. Today, three of the world's largest tube factories are in Russia, the Slovak Republic, and China. Although these factories make tubes that meet the requirements for guitar amplifiers and audio equipment, the resulting sound quality is often less than it should be. That's why tube weirdos hunt down new old-stock (NOS) tubes. Although tubes produced today and vintage tubes are built virtually the same, conductive materials in the old tubes were usually higher quality.

But here's the glitch: Regardless of testing, there's no way to know how much burn-time NOS tubes have left in them. You can pay a premium for a tube that dies on day one. Buying a tube that's been sitting around for half-a-century is a gamble.

Wathen Audiophile developed a cryogenic process they say changes the material quality and metal grain structure of tubes on a molecular level. Wathen says that process reduces or eliminates voids and imperfections in the material, and stabilizes welded and soldered areas. [Editor's note: The impact of cryogenics on guitars, amps, and parts is hotly debated. For another opinion on cryogenics and gear, read our columnist Heiko Hoepfinger's April 2016 “Bass Bench: Myths and Facts of Cryogenic Treatment."]

It sounded a bit farfetched, so I googled cryogenics and learned that racecar builders cryogenically treat engine parts to make the metal stronger to last longer and perform better. Also, cutting-edge knife makers strengthen their steel with cryogenics, and, since World War II, the U.S. military has required the manufacturers of various defense-related products to cryogenically quench steels as a way of insuring stronger metal with a lower failure rate. Convinced cryogenics was not snake oil, I laid out my dough for Wathen's CryoTone tubes.

Here's where it gets weird. After I retubed my amp, it ran quieter and had more volume, but the amp sounded harsh, like an icepick to the eardrum. I did some more web research and narrowed it down to the original JBL D130F speaker. It has an aluminum dust cap, notorious for a painful treble spike. (As mentioned, Vibroverb No. 1 had a Jensen C15N that was as warm as wool socks.) With crap tubes, I couldn't hear how bad that speaker sounded. It was like rebuilding your car's engine, taking it for a test drive, and learning that the transmission was shot. Vintage purists will call this heresy, but I bought a new, doped-up Weber Blue Dog and swapped it for the JBL. Problem solved, tone quest complete … for now.

But, as you probably suspect, the tone quest never ends. Even if you're a minimalist guitarist with just one amp, one guitar, one cable, and no pedals, there remains countless variables constantly changing your tone. With time, pickups lose their magnetic charge, tubes burn, caps and resistors deteriorate, speakers stretch, wood dries, attrition rubs off the finish, and strings start dying the moment they're stretched onto your guitar. Some of these changes improve sound; others suck the life right out of it. Tone is a moving target that requires nearly constant maintenance.

Before the overhaul, Vibroverb No. 2 had already cost me three times more than I had ever spent on any amp, so I was reluctant to throw good money after what was gone. But I'm glad I did, because pre-upgrade, I had five amps that could kick the Vibroverb's old, sagging ass. Now this amp sounds like God on a good day, transporting me back to 1983, when my tone quest began.