When I have a conversation about business with someone outside of the music industry, I often find it leads to a discussion of competitors or competition. These terms tend to place a comedic smile upon my face. Both of those words are almost always used by the person not in the music industry. As natural as the concept of competition is, the response I give is often received as unnatural. This could solely be because folks are not used to hearing how our industry actually operates internally.

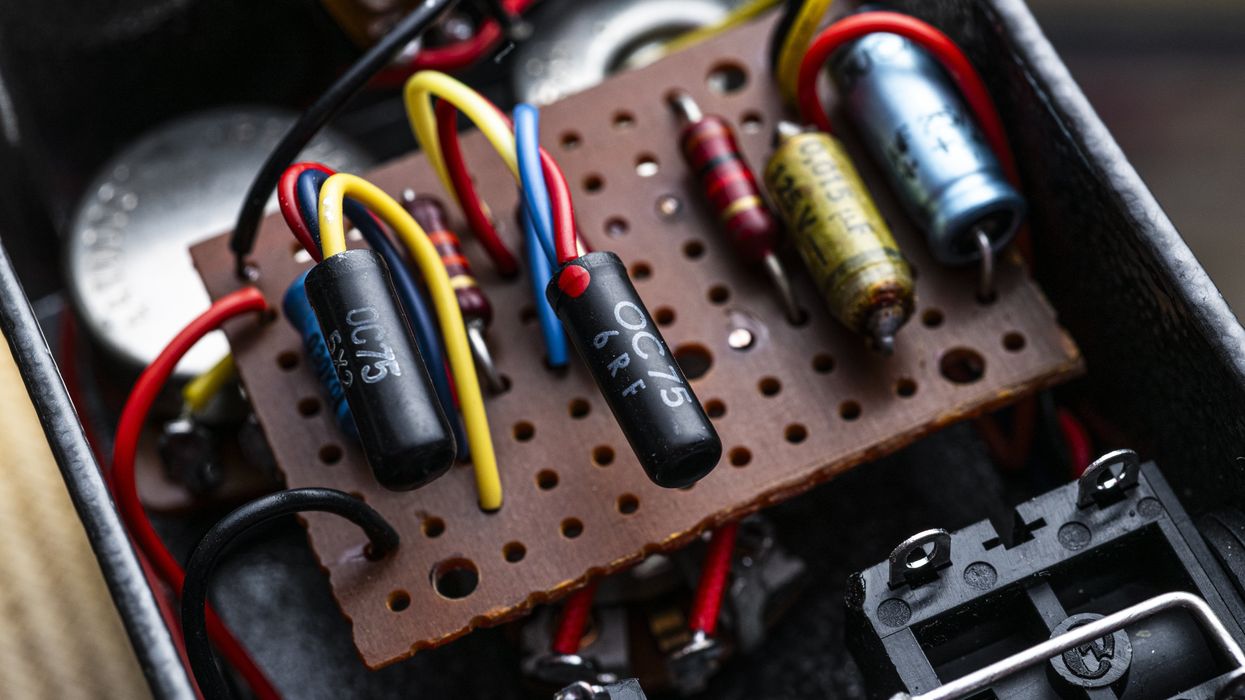

We have the immense pleasure of working alongside inspiring and creative companies. The word alongside often falls short of fully illustrating what is going on. This brings me to the part of the conversation that tends to catch people off guard. As for the aforementioned “competition,” there really isn’t any. At least not in the traditional sense. If anything, that is almost solely something perceived by consumers. Years back, a colleague was curious about how a certain pedal manufacturer achieves a specific feature in its design. This company is a big player in our industry—a household name in effects pedals. After my colleague sent an email inquiring about the feature, this company replied and attached a picture of a schematic. I have difficulty picturing the designers at Ford sharing engine diagrams with Chevrolet.

Another example of the collaborative nature of our industry: There are a handful of pedal manufacturers out there that have their circuit boards designed by other pedal companies. I am one of them. Smaller companies that are starting out have hired me to bring their ideas to life on the inside. This can lead people to ask, “Why are you helping the competition?” My main reply to that question centers on one word: respect. Let me elaborate on that. A start-up company might seek my services because they enjoy the products we make, they like my circuit board design work, and they know it will not directly conflict with one of our products. Our community has a deep, ethical respect for other pedal companies. I often find myself recalling late nights on the slopes of New Hampshire, skiing past a sign that read “Respect Gets Respect.” Outside of the monetary value and experience gained by working with other companies, this also reinforces and strengthens our community ties.

I often find myself recalling late nights on the slopes of New Hampshire, skiing past a sign that read “Respect Gets Respect.”

The idea for this month’s column goes back a year or two. However, the root of the idea extends back decades. It is inspired by the 1996 film The Rock, in which Sean Connery uses his extensive knowledge of the Alcatraz prison infrastructure to both infiltrate and escape it. In one scene, he and Nicolas Cage are locked in two cells. He manages to open the cell doors by tying together sheets from his bed and tying them to a wheel from the bed frame. Then, he’s able to swing the wheel over a release lever that opens the cell doors on his block. After opening the doors, he walks by an awestruck Cage and says, “Trade secrets, my boy.”

Trade secrets? Those two words have confused me since I first heard them together. I think the lack of deeper context is the culprit here. Was it, “These are trade secrets I will not share,” or was it, “Let us trade secrets with each other?” It is, by definition, the former. However, in our little corner of the world, it is almost exclusively the latter.

I often file information sharing into the philosophical drawer, followed by community reinforcement. Let us play out a scenario: A person reaches out to me about starting a pedal company and inquires about several aspects of the start-up process. First, merely reaching out shows an important level of ambition. Once I’ve learned about that person’s knowledge and aspirations, I proceed to answer any questions they might have. Armed with the information and tools, the ball is in that entrepreneur’s court. It is all going to come down to an investment of effort and persistence to achieve their goals. I would argue that whether the inquirer follows through or not, I was not the deciding factor. That person was or was not going to do it regardless of my involvement. It is also likely that they will develop their own processes and go on to share their findings with others–thus becoming another co-author of our community’s open book.

I wonder if other industries share a similar open-book policy? Also, if anyone has those Ford engine diagrams, send me an email.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)