There’s so much to discuss when it comes to bass playing. One of the most basic and valuable skills to be explored on bass—or any instrument for that matter—is placement, or where exactly to play relative to the beat. To a certain extent, this can be a cultural question, decided by where one was raised or what one was raised upon. However, some musicians are more intentional about their choice of placement, and thus choose to study feel and the multitude of possibilities within.

Rhythm is one of the most misunderstood subjects in music. If I had a dollar for every time I’ve heard “he’s got great rhythm,” or “she can play in 7,” I’d be much closer to being rich. In reality, playing in 7—or 23—will never make up for one’s lack of rhythm! As much as rhythm is misunderstood, feel is an infinitely more enigmatic subject. For most, music either feels good or it doesn’t. The why isn’t easy to put into words.

In some cultures, babies learn to instinctively nod their heads to the beat as young as 6 months old, while in others grown adults sit motionless whilst listening to grooves as deep as canyons. Yet, in our modern culture, rhythm, groove, and feel reign supreme. If there’s one thing that’s true of these elements, it’s that inconsistency sucks. A musician who is unable to be intentional about where they place things is about as much use as a brick layer who suffers the same affliction!

Nowhere is that truer than on the bass. Playing a reggae bass line such as Bob Marley’s “Buffalo Soldier” ahead of the beat would be considered a terrible sin. Playing bass way behind the beat on be-bop would be equally as egregious. Some people believe that one is either born with good feel or not. I, however, do not support this view. Great feel, that thing that nobody knows they’re missing until they do, can certainly be improved via osmosis, by spending as much time as possible around those who already have it—if they’ll have you!

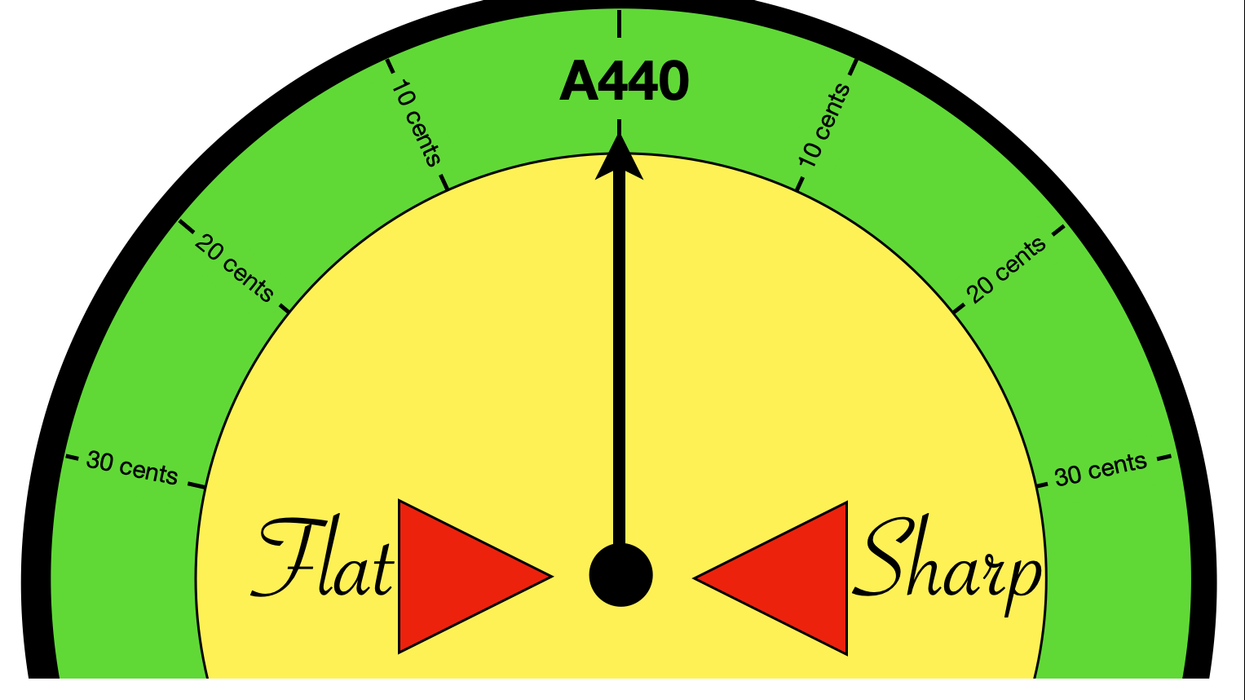

The “fat” or “wide beat” may sound like something from a ’90s rap verse, but it’s actually a concept that comes from much older jazz musicians. To such musicians, the beats within a given bar—1-2-3-4, for instance—were not singular fixed entities, but rather ranges. They might intentionally choose to play in front of, right on, behind, or even way … behind the theoretical beat (or grid, as we’ve come to call this in our post-sequencer world). Playing far behind the beat might increase groove and sound relaxed, while playing far in front might sound rushed, urgent, or even uptight.

A musician who is unable to be intentional about where they place things is about as much use as a brick layer who suffers the same affliction!

But the real magic is in the combinations. Even a drummer who seems to be playing right in the pocket—like Clyde Stubblefield on James Brown’s “Funky Drummer,” for instance—can intentionally have each drum landing on a different part of the beat: kick a hair early, snare a hair late, hi-hats right down the middle. And then the bass player—Charles Sherrell on “Funky Drummer”—would play relatively behind all of that! To the listener it just sounds funky, but there are multitudes of microscopic timing complexities that make funk or swing what they actually are. These musicians understood that great feel required getting off the grid, or, rather, knowing where things should lie theoretically, but intentionally placing them where they felt good. They’re like time travelers, able to negotiate the past, present, or future at will.

The actual “grid” came decades later, with the invention of sequencers and quantization. As more music became sequenced the result was more uniformity until, by the mid ’80s, lots of pop music sounded as if it had been created by robots. Ironically, what brought feel back to popular music was hip-hop producers sampling old breaks, like “Funky Drummer!”

By the late ’90s, producers like J Dilla lived “off the grid,” which is why their productions (primarily created on drum machines and sequencers) sounded so alive. Rather than using preset quantization maps (Akai, Steinberg, or Emagic’s futile answers to their sequencers’ lack of feel), Dilla created his own, based on what he heard earlier drummers, like Clyde Stubblefield, doing. Dilla’s work with Slum Village and others created a whole generation of hip-hop inspired drummers and bassists who preferred their grooves wonky, and the rest is history!

So, what should all this mean to the modern bassist? We live in a world where time within music is a thing to be mastered. When you next sit down to transcribe Pettiford, Jameson, or Jaco, etc.—because you certainly should—don’t just listen for the notes and rhythms. Also pay attention to placement and feel. These are just as important. Pay attention to what drummers are doing and consider where you intentionally wish to play relative to them. Practice playing ahead, behind, or right on it, so that you can do any of these intentionally at will. Become a time traveler!