Not long ago, Metallica bassist Robert Trujillo wrapped the six-year Herculean task of creating a documentary about the life and death of his biggest influence: jazz great Jaco Pastorius. The film has been a labor of love, fueled by an impression the legendary bassist made on him long ago. “Jaco really moved me back in 1979 when I saw him live for the first time,” he recalls. “I just thought to myself, ‘This mysterious figure is the real deal and he’s really cool.’”

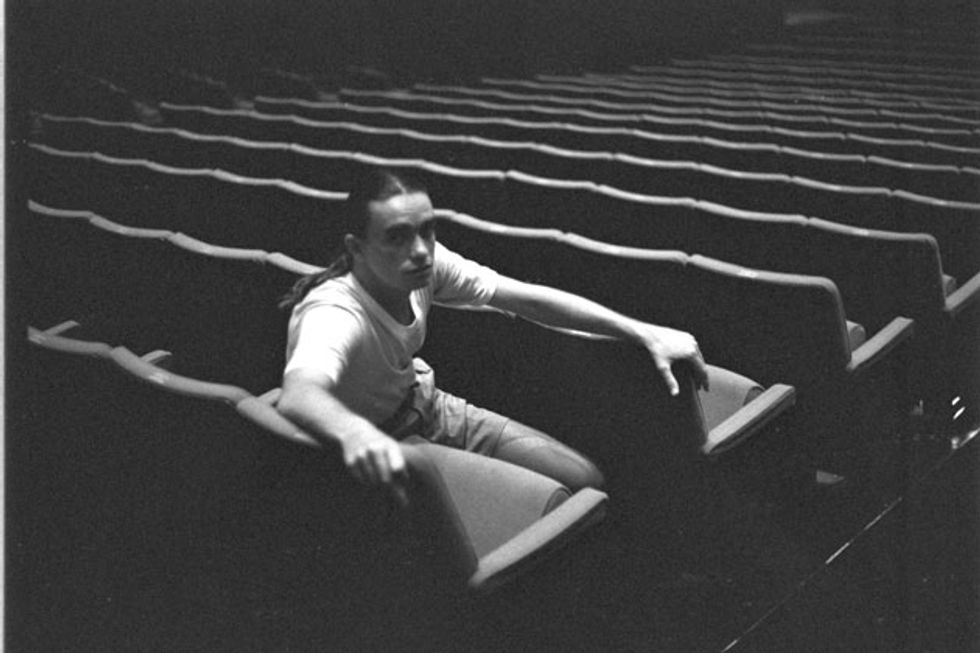

Best known for his pioneering fretless work, Jaco Pastorius unabashedly considered himself the greatest bass player in the world. He combined an R&B musician’s feel for rhythm with a jazz horn player’s melodic sensibility and applied it to a diverse array of musical styles. His work with Weather Report, Joni Mitchell, Ian Hunter, Pat Metheny, and his own Word of Mouth Big Band is universally recognized as groundbreaking. When he first burst onto the scene in 1976 with his debut solo album, Jaco Pastorius, he immediately inspired generations of bassists to rethink their approach to the instrument. He died in 1987 at just 35 years old.

Simply titled Jaco, Trujillo’s film—directed by Paul Marchand and Stephen Kijak—was officially released by Passion Pictures in November 2015. It chronicles the mercurial rise and fall of the world’s most innovative bassist through deeply intimate interviews with family members, friends, and bandmates. It also illuminates his life through concert footage, archival prints, video interviews, audio recordings, and home movies. Highlighting Jaco’s music and personal life, as well as the mental illness from which he suffered, Jaco delicately reveals the fragile artistic genius who consciously set out to redefine the bass guitar’s role in popular music.

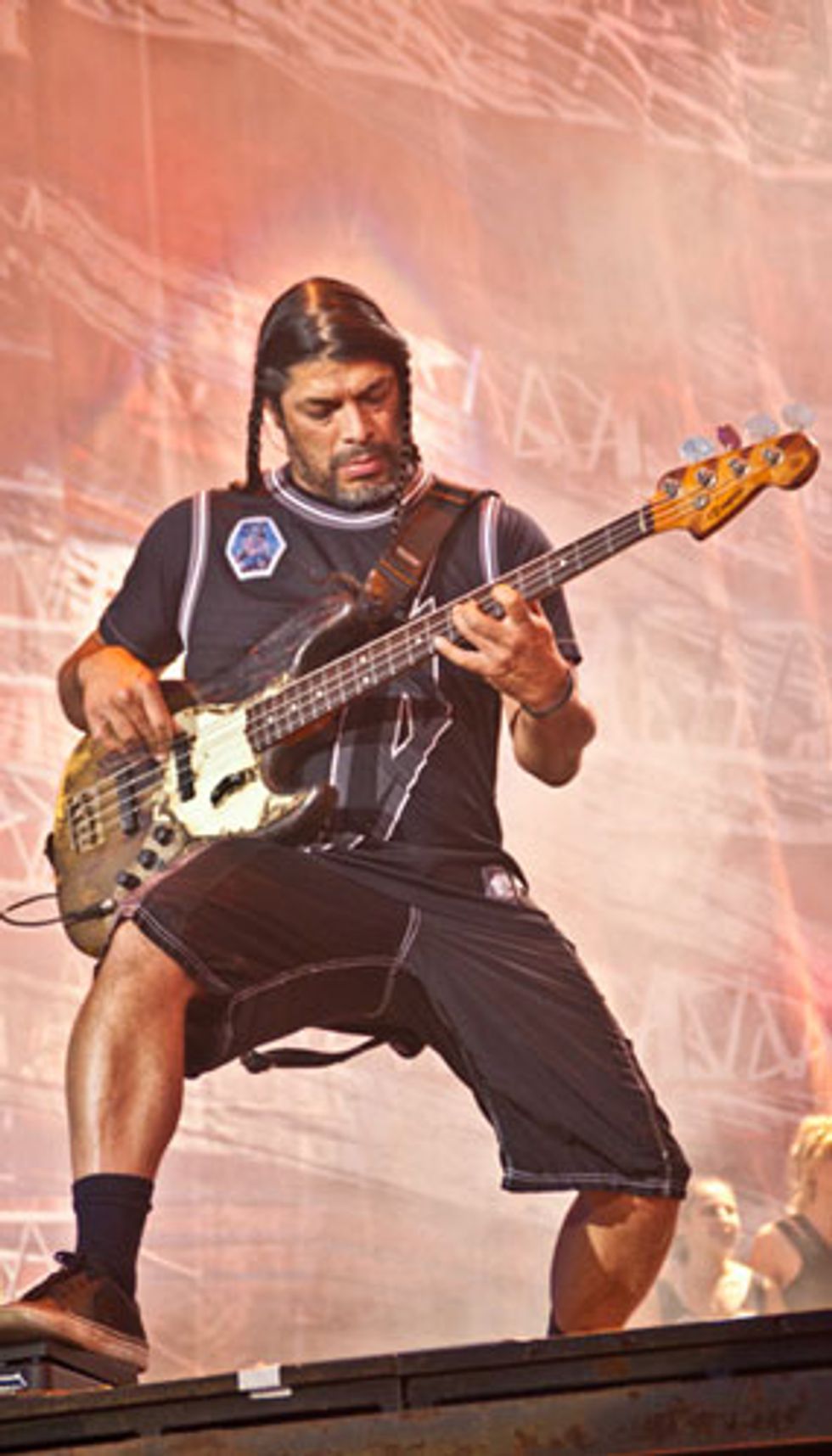

Producing the film was a first-time experience for Trujillo, who initially carved out a niche for himself in the ’80s as part of the Los Angeles-based crossover thrash band Suicidal Tendencies. He then launched the funk-metal group Infectious Grooves in 1989, before moving on to Ozzy Osbourne’s band in the ’90s and subsequently Metallica, where he replaced Jason Newsted in 2003. When not playing bass in metal’s biggest act, producing—and now promoting—Jaco has been his primary focus.

How did you first become involved in Jaco?

Loosely, my relationship with the project goes all the way back to 1996, when I first met Jaco’s son, Johnny Pastorius. But then, about six years ago, I went through Florida with Metallica and Johnny showed up with [Jaco’s childhood friend] Bob Bobbing, who was working on the film. He didn’t know anything about Metallica, but he was impressed that the bass player from this big-time rock band was influenced by Jaco and passionate about his influence. So, Bob pursued me to become part of the team.

Jaco Pastorius blended a jazz genius’ vision of harmony with prodigious technique that incorporated harmonics, bass chords, Latin influences, and hellacious funk—plus the charisma of a rock star. Photo by Brian Risner

What did you feel you could contribute?

At a certain point I realized that, for this film to actually be made, there needed to be money and I needed to put forth that money. I don’t like to use the word investment because it doesn’t really apply to documentary films. Documentaries are quite charitable, if you ask me. They cost a lot to make and yet they don’t make money. Just the licensing of songs and the archival photos and footage alone is an enormous expense. That’s why we had to raise money through a PledgeMusic campaign. I ran out of money, literally, in the last phase of the project. But I also get very passionate about things and I was consumed by this and felt like I was the one to pull it off.

What was your role as producer, aside from the financial commitment?

The role of a producer can be different in different situations. In this case, neutrality was key. You have different family members—it’s not like you have one or two. [Jaco was married twice and has children from both wives.] And then you’ve got friends. Jaco had a lot of friends who were very passionate about him, but they didn’t always get along with each other, so there was a lot of mediating. I like to refer to the position as “Switzerland,” being neutral, and really trying to keep things as cool and peaceful as possible. Ultimately, honoring and respecting the family was very important to me.

The Jaco film's biggest supporter, Robert Trujillo, is seen here rocking his bass wah for the intro of "For Whom the Bell Tolls" during Metallica's set at this year's Lollapalooza. Photo by Chris Kies

Were there any misconceptions people had about your involvement in the film?

I think people think I have this unlimited treasure chest of money, but it doesn’t work that way. I always say, “I didn’t write ‘Enter Sandman.’” I’ve been in Metallica for nearly 13 years and I’ve only been involved in one album [2008’s Death Magnetic]. So, I just want people to understand that, financially, it’s different for me.

With no prior filmmaking experience, what steps did you take to ensure a quality product?

I had a great film team—especially the director Paul Marchand. He was originally the editor and ended up taking over as the director three years ago. The magic that you see on the screen is Paul. He and I wrote it, but bringing that to life on the screen is a major challenge and he’s a very gifted filmmaker.

I also got a lot of great advice from people who had made great films, like Allan Slutsky (aka Dr. Licks), who did Standing in the Shadows of Motown, Sam Dunn, who did the Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage documentary, and Joe Berlinger, who did Some Kind of Monster for Metallica.

Was there anything that you discovered about Jaco through the making of the film that you didn’t know before?

Jaco suffered from bipolar disorder. So I’m better at understanding what’s going on there and how it can often be deeper than just drug addiction. There’s always going to be another side to the story. Back in the ’70s and ’80s there wasn’t as much awareness. There’s a little more help nowadays, but I don’t know, maybe Jaco didn’t want the help. It was a touchy situation because a lot of people did care for Jaco—it wasn’t like people didn’t care for him.

Groundbreaking work with Weather Report, Joni Mitchell, Ian Hunter, Pat Metheny, and his own Word of Mouth Big Band extended Jaco Pastorius’ influence well beyond the bass world. Photo by Brian Risner

You conducted over 75 interviews for the film. Were there any particular challenges to editing that much material?

A film like this takes time—you could never make it in one year. There was a lot of trial and error. We had multiple edits over the years. At one point I sat for six months with a clipboard at the director of photography’s house watching cuts, taking notes, and reviewing all of the interviews, just to see what was there.

There was also a time when we thought we were finished with the film, but then we received a box of audio cassettes of never-before-heard Jaco interviews from Conrad Silvert at DownBeat—this was from their archives. And then we also got photos from the Sony vault—outtakes from the first album—that had never been seen before. And then Joni Mitchell came onboard a couple of years ago. We had tried to reach out to her for four years and there was nothing. And then I met her randomly at a Grammy party. So, we really had to narrow it all down to an overview of his life, his musical accomplishments, and the bipolar disorder.

Is there a story you can share that didn’t make it into the film?

I met a guy in New Zealand who was Jaco’s bass tech for a couple of years at the tail end of Weather Report. He had some great, funny stories. Jaco liked putting live crabs in his pockets before going on a flight. Back then you didn’t have the security that you have now, so he would unleash the crabs onboard and everybody would run around screaming. Jaco called these pranks “wipes.” He’d pull “wipes” on people, like lighting a firecracker and putting it in someone’s pocket when they weren’t looking.

There are several excerpts from the Modern Electric Bass instructional video. Why was that so important to this film?

Jerry Jemmott was Jaco’s favorite bass player and Jaco wanted him there [in the video] to make that statement. At the time, Jaco couldn’t get a gig playing in a band or recording. So the grand statement for him was to make this video to help other people. In his mind, he probably thought it would bring money in to help his situation and help his family. He also felt the need to educate people in the best way he could.

There’s a scene in the movie where you’re onstage with Metallica playing Jaco’s now-infamous “Bass of Doom.” How did it come to be in your possession?

It’s a story in itself and I don’t know all of the details. The bass went missing for over 20 years. Some say it was stolen, which is what Jaco said, and some say he gave it away or traded it. All I know is that the bass reappeared in New York City, a legal dispute erupted, and attorney bills were the only thing going down. It was a situation that would have put JPI [Jaco Pastorius, Inc.] into bankruptcy. I felt there was a lot of emotion and tension around this situation. I’m not a collector, but I felt that I could help. So, I sponsored the money to get the bass out of the situation that it was in. The bass is in NYC with Felix Pastorius [Jaco’s son from his second marriage] most of the time these days.

There seemed to be a lot of conflicting reports about what was actually going down at the time.

People think that I found out who had it and I went there with a lot of cash and said, “Here, I want that bass.” That’s not the case at all. I just felt the need to help with the situation. You have to understand that the instrument meant a lot to Johnny and Mary [Jaco’s children from his first marriage]. It was a really important part of their life.

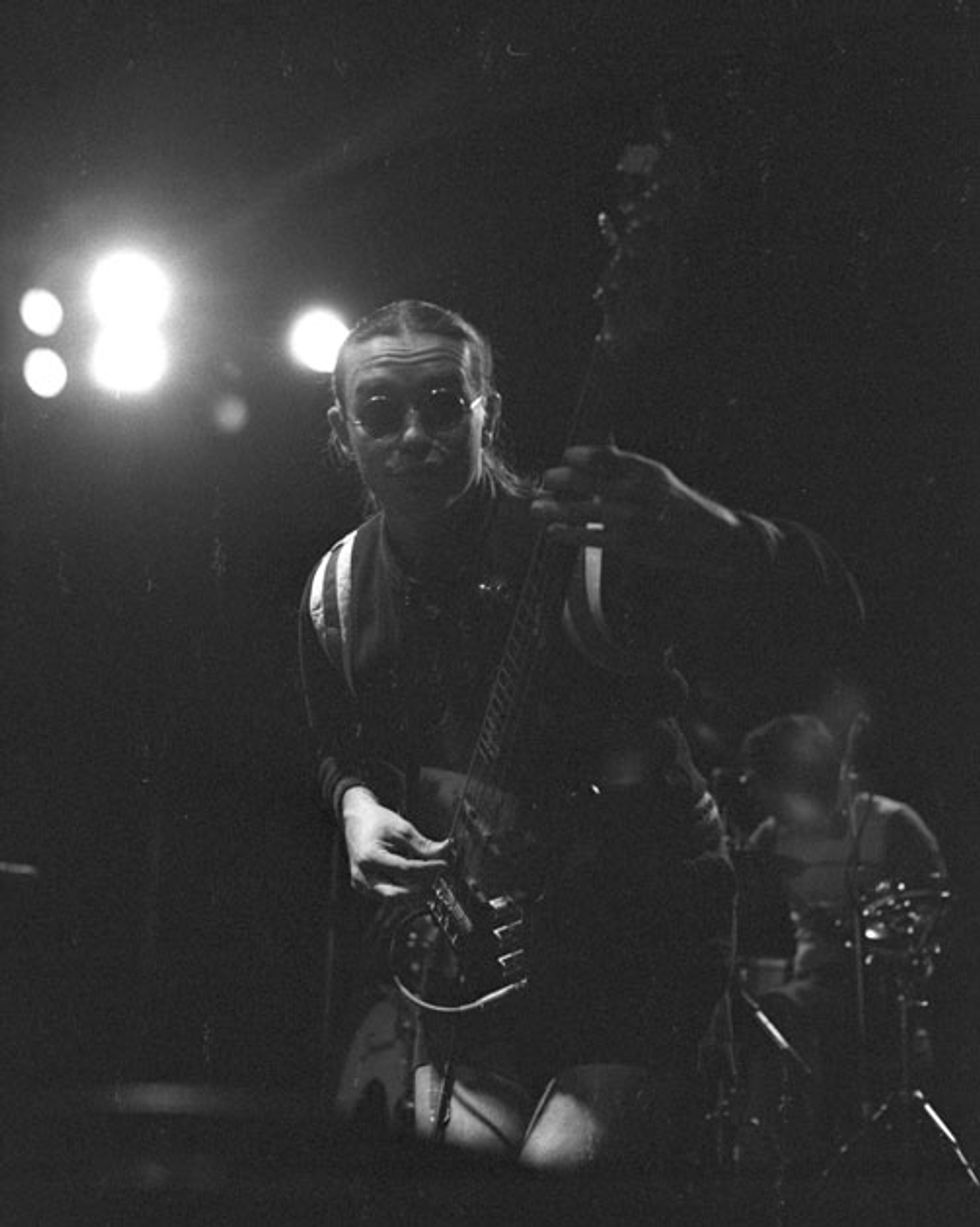

“I’ve come to really believe that Jaco wasn’t about wanting people to do exactly what he did or to learn his songs,” Robert Trujillo explains. “It was about being free, creatively, and using the tools he provided to compose in all styles of music.” Photo by Brian Risner

How does it play?

It is a beautiful instrument. It has a personality in itself. There could be a movie just about the bass alone, like the Red Violin, because it had a life of its own, even beyond the years with Jaco. Where did it go? What happened to it in those 20 years? No one really knows.

Did you ever see Jaco play live?

I did see Jaco play four times. I’m 51 years old and I was very lucky, as a young teenager, to have seen him play and witness the brilliance.

Did he have any influence on your gear preferences?

Gear-wise, there was a time when Jaco often used a chorused-out sound that was very dynamic and, though I don’t use it that much anymore, I did use it quite a bit with Suicidal Tendencies.

What influence did he have on you as a player and songwriter?

There are some melodic quotes I do on the fretless bass that were inspired by Jaco, like the intro to “You Can’t Bring Me Down” [from Lights… Camera… Revolution! by Suicidal Tendencies]. There was a lot of that influence on The Art of Rebellion as well. With Infectious Grooves, because I was the main writer, every song we ever did was inspired by Jaco. Yeah, there were moments of Anthony Jackson or Parliament-Funkadelic—we were taking influences from everyone. But for me, Jaco was always the main influence.

What was it in particular that was so inspiring?

I wasn’t necessarily trying to play Jaco compositions note-for-note. I was more into taking the technique or the feel and creating a song around that. It was about composition—using harmonics, for example, but using them in a song formula. That was how I used the tools he provided.

After going through this journey with this project, I’ve come to really believe that Jaco wasn’t about wanting people to do exactly what he did or to learn his songs. It was about being free, creatively, and using the tools he provided to compose in all styles of music. In that way, he was a huge inspiration.

YouTube It

In this brief, tantalizing trailer, Joni Mitchell, Bootsy Collins, Flea, Herbie Hancock, Jonas Hellborg, and Wayne Shorter offer insights into Jaco’s life, legacy, and creative genius.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)