“I need to be in a punk band at the same time as I need to be playing free improv at the same time as I need to be playing songs,” Wendy Eisenberg explains, detailing their creative process. “All at the same time—otherwise none of the practices will work for me.” Listening to Eisenberg’s work, this is easily understood.

Take Eisenberg’s new record, Auto, for example. The album opens with the ballad “I Don’t Want To,” which combines clean sounds from Eisenberg’s ES-175 and glitchy electronics à la Jim O’Rourke and David Grubbs’ experimental creations as Gastr Del Sol. “Centreville” follows, with Eisenberg taking a tech-y and angular approach to guitar riffage, followed by the sunny, jazz-pop groove of “No Such Lack.” In just three tracks, Eisenberg has covered plenty of ground and the album proceeds with sustained versatility throughout.

Each stylistic jump on Auto is studied and focused and serves a distinct musical purpose, so the album makes the case that this sort of big-ears, genre-hopping approach is home for Eisenberg and is an aesthetic in and of itself. It’s no surprise when Eisenberg name-drops composer John Zorn’s iconoclastic Naked City band—whose extreme genre-pastiche approach is both groundbreaking and truly incomparable—as part of their education. “I went to NEC [New England Conservatory] for their Contemporary Improv masters,” the guitarist says. “It happened to coincide with Zorn’s 60th birthday concerts, where I got to play a bunch of Naked City parts.”

After college, Eisenberg continued to have multiple stylistic irons in the fire. Eisenberg was quick to become a regular player in the New York City experimental scene, where they stayed connected with Zorn, who released The Machinic Unconscious, Eisenberg’s trio record with bassist Trevor Dunn (Mr. Bungle and countless Zorn projects) and drummer Ches Smith (Marc Ribot, Tim Berne). Meanwhile, Eisenberg was actively involved in the Western Massachusetts music scene, living there until recently moving to New York, and worked with several rock and noise bands including the Birthing Hips, whose dissolution inspired Auto.

It’s easy to hear similarities between Birthing Hips—whose own “genre-play,” as Eisenberg explains, is quickly identifiable, especially on “Strip Tease,” where Beethoven’s “Ode To Joy” theme can be heard accompanied by a blast of noise-rock ripping—and Auto, but the latter feels much more nuanced and personal. As a player, Eisenberg takes on such a wide variety of playing approaches, from angular riffing to contrapuntal chord melodies to short flashes of bossa nova comping and so much more—all of which seem to come naturally and in support of the well-crafted songs. Producer Nick Zanca contributes much of the synths and electronic elements that color and surround Eisenberg’s playing, providing a cohesive sonic landscape, while Eisenberg’s warm, plainly-stated singing navigates the conceptual changes and helps form a united whole to the album.

Eisenberg is a sharp musical thinker, so we took this opportunity to catch up and discuss Auto and to pick their brain about everything from practice materials to improvisation and composition concepts.

What about improvisation is important to you and your guitar playing?

Improvisation, on the guitar, is a way for me to know the guitar better. At this point, because I’ve been so married to the guitar for years, I feel like by exploring the guitar I’m actually exploring myself and I feel like improvisation actually affords you that. If you’re doing composed work, you’re exploring something outside of you. Maybe I’m selfish, but there’s less potential for something there for me than the self-exploration that is part of improvising on an instrument that you know.

I think what’s important about it is that your body can surprise you. So, if you’re doing a discipline that has less to do with the regurgitation of ideas—in composed music or in genre-specific improvised work—if you’re going against those techniques, your literal physical intuition starts to matter differently. A lot of my vocabulary and my approaches come from whatever my body wants to do on the guitar at the time, which usually just has to do with me stretching out an impulse. So, if I want to play a little cluster or a melody, then I’ll want to stretch it out using a shape or developing it in some way, rhythmically or off the fretboard.

Would you share some of the background behind writing Auto?

I had this improvising/composed genre-play band called Birthing Hips, and when we broke up I was kind of worried that I wouldn’t be able to write the same way.Birthing Hips didn’t work out and I was writing as a way to take stock of what musically was still there for me to say. I was really approaching the composition of each song like I wanted to use my influences, but not consciously. I wanted to be as true to the experience of loss that I had from the band and also from the incredible seismic mid-20s changes that were happening at the time.

While writing the album Auto, Wendy Eisenberg had two guidelines: “The song had to be good, which is hopefully a challenge that all songwriters need to follow, and the song also has to convey with accuracy and, hopefully a little bit of grace, the emotional state via the music.”

Musically, there are some things that are more stock than others. There’s a song on there called “Genre Fiction” that’s basically a folk song, and there’s other stuff that’s super complicated, like “Centreville.” That’s about the divorce between your brain and your body when you have to sing and play at the same time.

All of these things were little challenges I set to myself: The song had to be good, which is hopefully a challenge that all songwriters need to follow, and the song also has to convey with accuracy and, hopefully, a little bit of grace, the emotional state via the music.

What are those influences you’re exploring on this album?

There’s a lot of Arto Lindsay’s songs. Ted Reichman [composer and Eisenberg’s former professor at NEC] once told me that my songs were like his and I didn’t think it was true and I slowly wanted to make it true because his songs are great. I was really into his Mundo Civilizado kind of stuff, because the fact that he could do that and [no-wave band] DNA and [avant-pop duo] Ambitious Lovers and everything, I mean…. I think it’s him and Eugene Chadbourne that care as much about improvisation as they do about songs on the guitar.

So, I feel like I was coming from an Arto Lindsay place and also a João Gilberto and Juana Molinaworld, where the songcraft is super important, but there’s also humor and exploration. Songs can so easily become stock and improvisation can so easily become stock, so I wanted the record to be at the midpoint of innovation in both of those genres.

I was wondering if Gastr Del Sol was part of that.

I like to listen to Gastr Del Sol and definitely the way the records are produced informed the production 100 percent, but I never think of trying to write the way they do. I think the producer on the record was thinking about that a lot, because there’s that acoustic guitar and electronics thing.

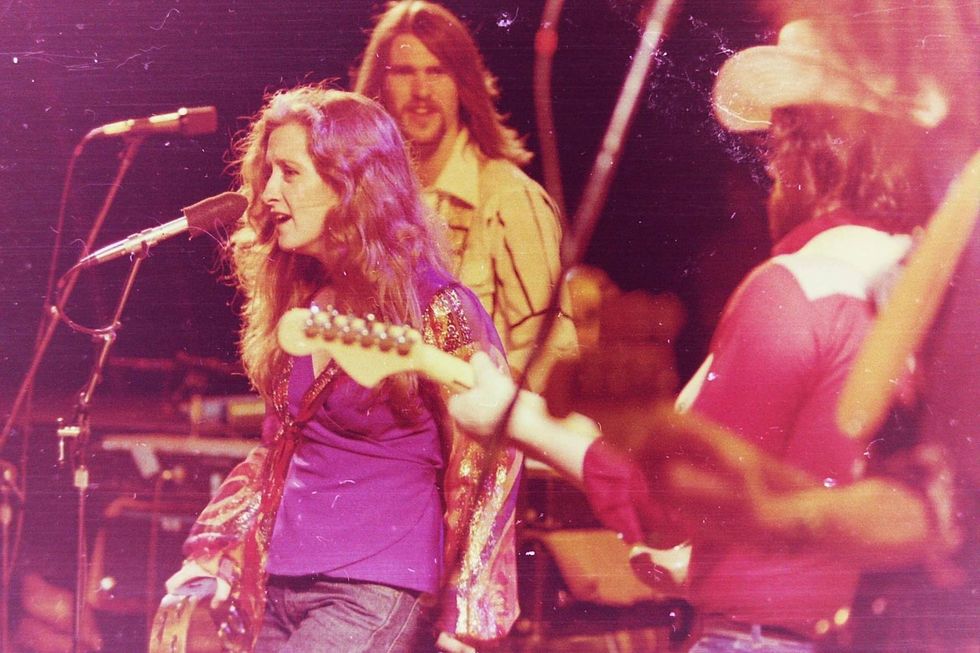

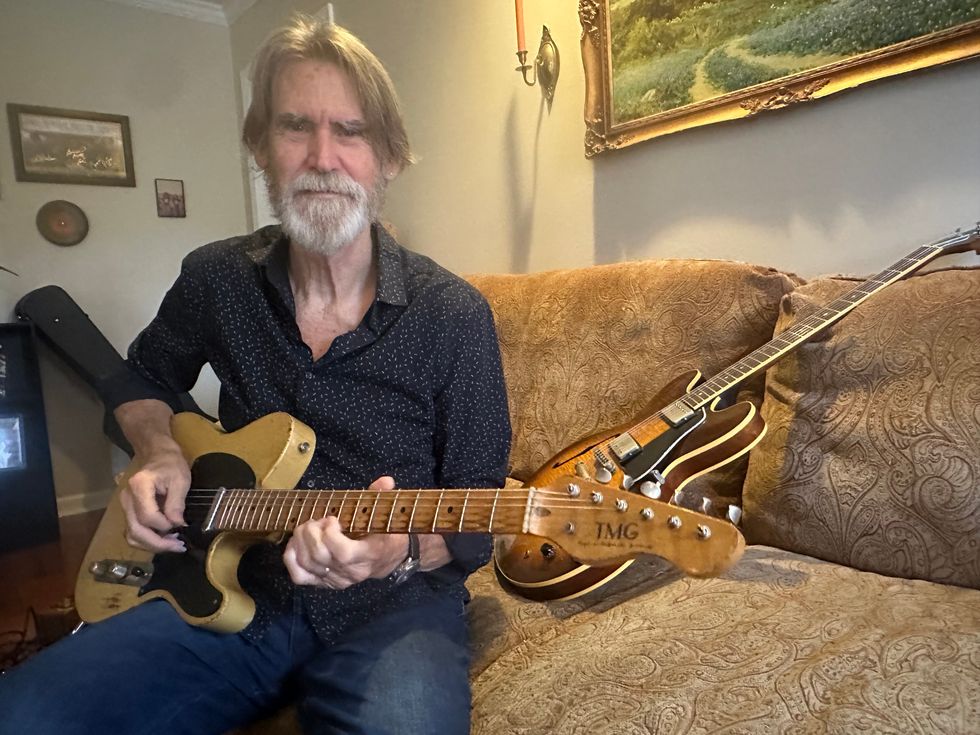

“I play the same guitars that I’ve played since high school,” says Wendy Eisenberg. That includes this 1989 Japan-made Fender Jazzmaster, which Eisenberg describes as “a very disconcerting color of yellow.” Photo by Ellery Berenger

How is the guitar part of your writing process?

At the time that I was writing this, I would be doing a lot of melodies away from the guitar, so I’d be walking around and singing to myself, which I didn’t really do until writing this.

In the act of writing, it’s usually like a one- to three-hour process, and I just sit there with the guitar and let it speak to me. It’s kind of like you get out of it what you put into it. If I’m practicing a lot that day, then I’ll write something like “Centreville” or “Futures,” which have a more linear thing, because I was practicing a lot of lines and trying to get my improvising melodies happening. I’m really into [Cuban guitarist and composer] Leo Brouwer, and when I was practicing him a lot, my songs sounded more in his harmonic world.

I just let it speak. I feel like the guitar has better ideas than I do. At this point, I feel so conversant, technically, that if I were to presuppose that I had a better idea than what the guitar would suggest to me, then that would be a really supreme arrogance and I wouldn’t want to cop to it.

Do you notice much difference between the stuff you write away from the guitar and the stuff you write on the guitar?

I feel like the stuff that I write away from the guitar is usually the most emotionally honest stuff. I’m just happier when I’m playing, so I have less emotional baggage to deal with or something.

Usually, if I’m writing away from the guitar it’s easier for me to stay honest, where if I’m writing with the guitar, I’m just so stoked that the guitar sounds so good. Not just because I’m playing it, because I’m not that arrogant, but honestly the instrument is just so seductive to me that it brings me enough joy to obscure whatever feeling drove me to want to write a song anyway.

I’ll marry shit that I wrote from walking around with the guitar part that happens. There’s some temporal dissension at play where I’ll just be singing a thing that I wrote a couple days ago over a guitar part that I wrote in the moment.

Of course, in the way that you’re talking about, the guitar can be therapeutic.

Oh my god, yeah, absolutely. The same with the writing of melodies. The fact that it’s possible to walk around and have a melody come into your brain is nothing short of a miracle.

What’s been really hard for me since moving to New York is writing a song that isn’t just expressing stupid and completely useless mirth on how good the rhythm of things feels. It’s only been a month and half, so probably in two more months I’ll write a shitty dirge about how much of a bummer it is to be here.

Since moving to New York, I’ve been playing a lot of free music in parks and stuff. I was in Western Mass., and the culture there is more about songs. There’s a great noise scene, of course. There’s so much more visual and cultural noise in this city that it makes me think that playing noise things is being more in tune with it.

One of the records that really influenced Auto is Blemish by David Sylvian, that has Derek Bailey on it. It’s so weird. The guitar parts that Derek Bailey sent into David Sylvian that Sylvian later sang over is closer to the music that I want to make. But I wouldn’t have known about that record without the producer of Auto, Nick Zanca, showing me that it existed.

Guitars

1989 Fender Jazzmaster

1959 Gibson ES-175

Amps

Fender Princeton

Rickenbacker TR35B

Effects

Boss PS-6 Harmonist

Fulltone Full-Drive2

ZVEX Fuzz Factory

ZVEX Ringtone

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EPN115 Pure Nickel (.011–.048)

D’Andrea Pro Plec Small Round 1.5 mm

On “Hurt People” you have that jazzy chord melody and on “Urge” there are some really jazzy chord moves. Since you mentioned practicing, I’m curious if you remember what you were practicing when you wrote those?

I’ve been obsessed with the great songbook for my whole life. I love standards and, specifically, I love the way Blossom Dearie plays standards. I think with both of those songs, I wanted to write jazz standards. I wasn’t practicing moving through chord melodies in probably the way that I should if I want to be better at that, but I was playing a lot with voice leading and what it means to descend. Because guitar is such a weird Rubik’s Cube folded in on itself situation, when you voice lead you can only go down so far in certain ways, if you’re playing with descent. I’m talking really about “Urge” here—when I voice lead and I’m trying to make all the downward motions, the guitar is gonna run out at some point and I’m gonna reach the headstock, so you have to think about suspension in a different way.

So, I was thinking about the great songbook, but also about how much time you can spend in one zone of the fretboard before the modulation really needs to continue.

What guitars do you play on Auto?

I play the same guitars that I’ve played since high school, which are a Jazzmaster from 1989 that’s Japanese and is a very disconcerting color of yellow. That’s on some of the songs, and on most of the songs I play a 1959 ES-175, which I’m the luckiest person in the world to have. It’s just a sensational guitar. I thought I was gonna be a bebop guitar player, which is so funny now, and I was like, “What do bebop people like?” I looked that up and it was that ES-175. My mom and I looked it up on eBay and found that for way less money than it should’ve been worth, so I bought it on installment from my mom.Any acoustic guitar is probably the archtop played acoustically or played really lightly though an amp.

For amps, I use a Fender Princeton or a Rickenbacker TR35B amplifier that’s a 1x15, made for bass. It’s a really weird instrument of itself that I’m totally obsessed with. Using tubes and touring is just a fool’s errand, I think.

For pedals, I feel a little funny saying this because Fulltone is shitty and racist, but I use a Full-Drive2 and I need to find a substitute for that because I use that pedal as my neutral when I play rock music. I was thinking about getting a Box of Rock, because I love ZVEX and I use a Fuzz Factory and a Ringtone, and the Boss PS-6 Harmonist.

At this point, I’m still kind of simple and a little stupid and there’s so much to the guitar in standard tuning without any pedals that has yet to be explored, so I tend to be pretty minimalist these days.

Eisenberg chases unique guitar sounds by experimenting with different techniques, like using fingernails and picking with both hands. Photo by Peter Gannushkin

You’re clearly very into guitar stuff and practicing. What do you love to practice?

I like to see how many different sounds I can get out of my archtop. These days, it’s really fun to see what I can do with fingernails and what I can do with picking with both hands.

It’s tough, because I spent a large part of my life really interested in guitar guitar stuff, like Brouwer, Ted Dunbar’s work, Ted Greene’s work … really just studying from these masters. At this point, I’m taking an approach that’s a little bit more from Joe Morris, which is that I like to follow whatever the guitar is telling me that day and then develop on it with a more conscious mind, by which I mean I’ll improvise and if something really amazing happens while I’m improvising, I’ll zero in on it, then develop that.

The way that I’m exploring the guitar now is a little more intuitive and has to do with being receptive to how long a decay is, for example. Sometimes I’ll just pick up a guitar and play an open A string and see how long it takes for it to die down and see if it catches one of the reflections of one of the walls in my room, and play to the space.

For example, I like to take my archtop and play it with the Rickenbacker at Nick Zanca’s space. We play electroacoustic improv together and he plays a Wurlitzer through Max MSP and I play guitar. One of the things about his studio is, when I play a low F# on the guitar, it feeds back in a way that sounds like a cello, and it only happens in that room. So my project recently for getting to know the guitar better is about getting to know the space that I’m playing the guitar in better. And that just comes from doing it in the same place all of the time.

The form of Wendy Eisenberg’s “Futures” slowly emerges amidst an angular and fluid solo guitar improvisation. The tune begins to deconstruct around 2:47 amidst a flurry of extended techniques, resolving into a final theme that shows off Eisenberg’s voice-leading chops.

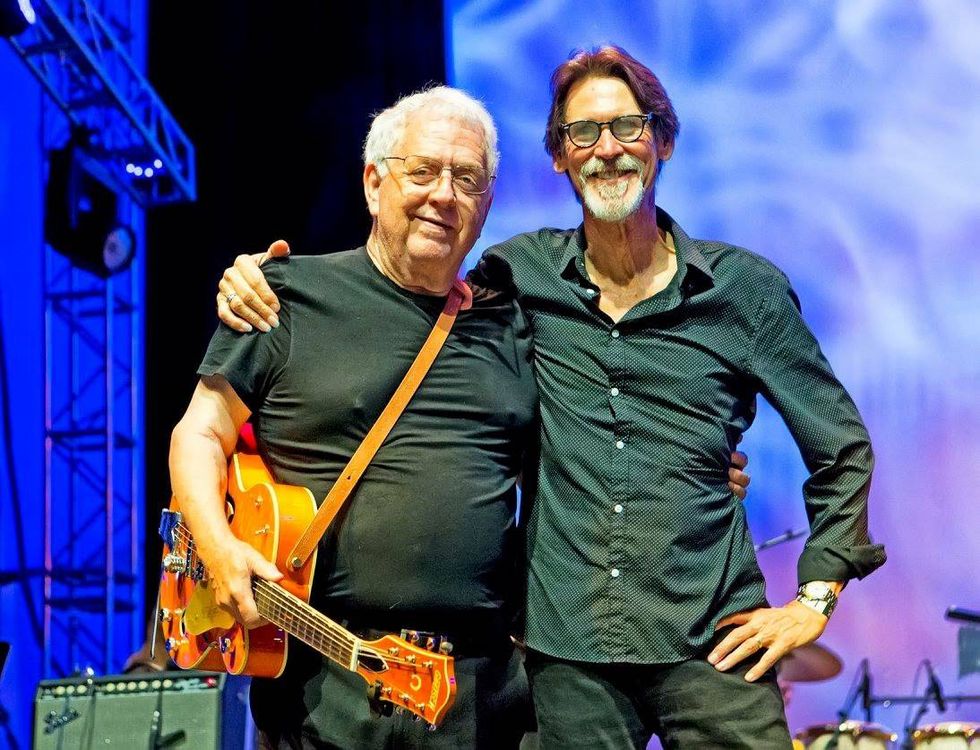

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski