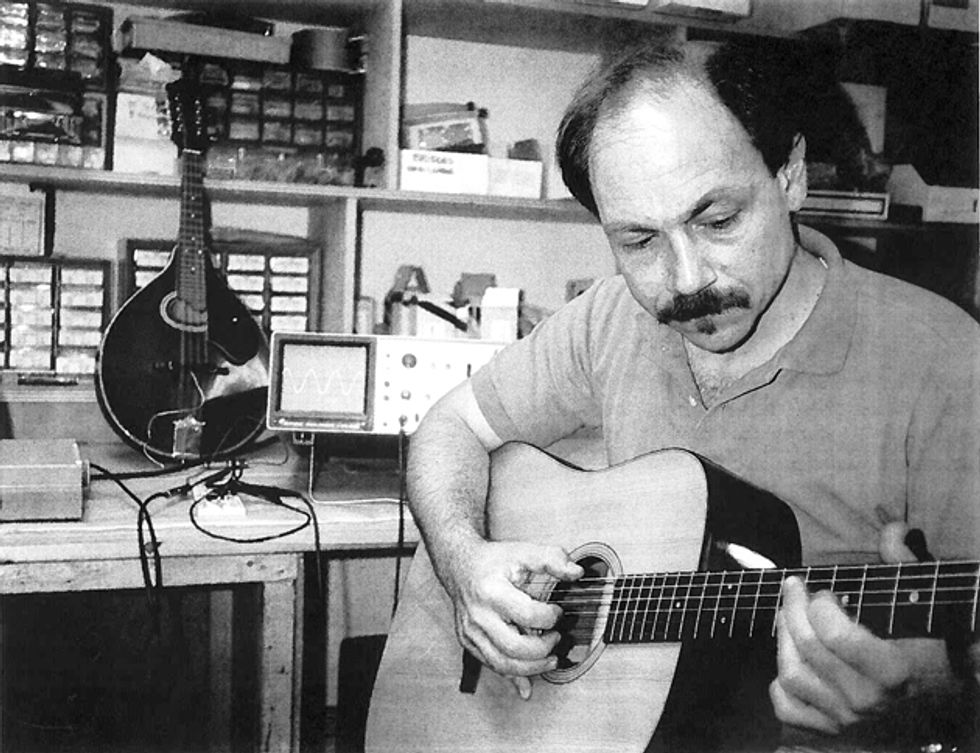

One of the benefits of the job: Here I am in my shop in the mid ’80s, playing my guitar that’s outfitted with a second-generation Martin 332 Thinline pickup.

It was 1985 and life was good. I was living in a little house outside Boston in Medford, Massachusetts, playing bass with a jazz quintet at night, and making pickups in my basement during the day. My two part-time employees and I were building bass and violin pickups, as well as acoustic guitar pickups we’d been supplying to Guild for about a year. It was a veritable cottage industry!

The year was also a pivotal one for me. One afternoon, I answered the phone and a gentleman named John Marshall introduced himself. John was a product manager at Martin and he told me they wanted to source an acoustic guitar pickup to replace the Martin Thinline 332 that had been on the market for about two years. I told him I was confident that we could design and supply what they needed, and then asked him to send me a product requirements document with specifics.

“It’s pretty simple,” John told me. “Design us something that will fit under a standard 3/32" saddle that’s reliable, easy to install, and sounds better than what we’re currently selling.”

I told him I understood and that I’d have something for them to evaluate in three or four weeks.

I’ve always felt that design—with rare exceptions—is really redesign. The best way to progress is to learn from the past. With that in mind, I purchased a Thinline 332 and installed it in a guitar.

Within minutes, I completely understood why Martin was looking for a new design. First of all, the installation was a real chore. The pickup was a small, rectangular bar that was covered with copper foil and had a miniature coaxial cable exiting at the bottom-center of the unit. It felt very fragile right out of the box and there were crimps and wrinkles in the copper. Not only that, the installation instructions required that the installer remove material from the bottom of the saddle (equal to the thickness of the pickup) and then split the saddle into two equal lengths. When that was done, each half of the saddle needed to be shortened slightly so there would be a gap between the two sections when the split saddle was reinstalled.

Once the pickup was installed, I plugged the guitar into an amp to check it out. The string response was nice and balanced at first, but the 6th-string response seemed to weaken after some more aggressive playing. That’s when I noticed that half of the split saddle had shifted in the slot. This meant that the three lower strings were no longer aligned with respect to their individual sensor elements. After I moved the half piece of saddle back to its proper location, I played the guitar some more and was really struck by how the amplified sound was drier than a peanut butter sandwich in the desert.

So there it was: I totally understood the basis of the design requirements laid out by the Martin Guitar Company. The Thinline 332 certainly fit in a standard saddle slot, but it was difficult to install, inherently unstable and unreliable (due to its split-saddle design), and the amplified sound was lacking in dimension and complexity.

For me, the creation of a new design is a highly iterative process that combines principals and methods I already understand with the excitement of exploration and new discovery. I can rarely predict where exactly the exploration will lead, but I have learned that persistence and patience always get me to that wonderful aha moment.

When I’m at the beginning stage of any new design, I always ask myself what the design needs to accomplish and what materials are best suited for its function. I then create a number of rough, concept sketches and a list of all the types of materials that might be useful. It’s at this point that the real fun begins: I’ll pick several concepts and start building rough prototypes for each, all at the same time.

Rather than building one prototype at a time, I find this multiple-design approach has several advantages. It’s quite demoralizing to put hours into building a single prototype, only to have it totally fail to meet its performance expectations. When I build several different designs at the same time, I usually find that at least one prototype will perform quite well, so at least I spare myself the disappointment of total failure. I also find that being able to do a comparative evaluation of a group of designs—rather than a subjective evaluation of just one—greatly accelerates the process.

Once a solid design is established, I can then begin the design detailing. And this is the most critical part of the entire design process to me. “The details are not the details. They make the design,” said Charles Eames, the legendary filmmaker and industrial, architectural, and graphic designer. I couldn’t agree more.

Next time, we’ll get under the hood and take a closer look at the design details of the original Martin Thinline 332. We’ll also talk more about what would become the second-generation version of the pickup.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)