Over its 11-year existence, Brooklyn-based psych-folk collective Woods has made a comfortable home for itself writing and producing albums that hide between genres and transcend sonic definitions—without sacrificing musical personality for the sake of style hopping. With its ninth, City Sun Eater in the River of Light, Woods has rendered yet another glowing portrait of that personality, painted, as usual, in songs that naturally flow where they may.

City Sun Eater is an adventurous affair that finds frontman/guitarist/principal songwriter Jeremy Earl exploring his art along a path through West African-infused psych-rock meditations, the dusty back roads of steel-guitar Americana, spaced-out dubs, and rhythm-heavy freak-outs—all tied together by his smooth falsetto vocals. Stepping away from his usual 6- and 12-string duties, Jarvis Taveniere co-piloted the album by writing songs with Earl, engineering, co-producing, and laying down bass tracks.

“It’s all about having fun and trying different things as a band at this point,” Earl explains. “Most important, we’re focused on being completely free and open to trying anything we want and experimenting in the studio. But having fun is the only real expectation we have. For a while we were doing one record a year, and when we started touring more that pace became harder to pull off, but it worked out because we also wanted to let our albums simmer a bit more before making new statements. Now I let the songs come naturally—I don’t try to push any kind of deadlines.”

Just as City Sun Eater in the River of Light was hitting the streets, we spoke to Earl and fellow fun-seeker Taveniere about creative goals, intertwined guitars, arranging on the fly, and how to make simplicity speak volumes.

Jeremy, what role does the guitar play in your writing process?

Jeremy Earl: It’s my voice and a guitar providing the basis for almost all of our songs. A lot of the time, I work off of a vocal melody first—something that just pops into my head while I’m driving or something—and I’ll get home and sit down with a guitar and work out a chord progression that will work with it. But a lot of the time, it’s casual strumming around the house that allows inspiration to strike, and I then follow it.

That said, I played all of the guitar on this album. Typically Jarvis handles more of the melodic leads and I’ll handle more of the solos and rhythm guitar, but for this one Jarvis was engineering as well as handling the bass, so he was otherwise occupied. And once we got going into overdubs, I was just flying and ideas kept coming out. Live, Jarvis is playing most of the lead stuff that I can’t do while I’m singing, and backing up the band with other guitar parts.

Where do you come from as a guitar player?

Earl: It’s kind of weird, because I don’t consider myself much of a guitar player, really. My technique is pretty sloppy, and I never had lessons or anything like that. I started as a drummer, but fell into songwriting and got very swept up in that. I then learned basic chords just to form songs, which came fairly easily. So I formed my guitar playing around this loose, almost caveman-esque philosophy of “use what you’ve got” without concern for being flashy, trying to be a little more creative with what tools I have while keeping things minimal.

Jarvis, did you play much bass prior to tracking this album?

Jarvis Taveniere: It just happened over the years because of recording. I never thought of myself as a bassist, but once I started paying attention to it, I really locked into it and a whole new world opened up.

To your credit, the bass on City Sun Eater doesn’t sound like a guitarist jumping over to bass, which can lead to bass tracks that aren’t very rhythmic.

Taveniere: Yeah, I definitely don’t like that style of “lead” bass playing. There are certainly recordings that have that kind of playing that I don’t mind, but I prefer bass players that are thinking about the bass as a rhythmic thing. The goal of any rhythm section should be to elevate the song and take it to the next level without getting in the way or being too flashy. I like elevating songs in a subtle way—that’s why I find the bass so much fun. Traditional rhythmic bass playing is so exciting because you can do a lot with a little—the accents and the subtle touches. Playing bass is kind of like a math problem in which I want to see what I can do to negotiate things between the drums and the guitar. Like, “How can I be melodic and rhythmic and find a happy middle that serves the song?”

Was it difficult to learn Jeremy’s guitar parts from the record to perform live?

Taveniere: I think I figured them out before Jeremy could remember what he played—because I was there tracking them with him. A lot of those parts were written on the spot, too, and we’d work them out together a bit, so I understood the parts well already.

When you’re playing live, do you vary those parts to add your own flair?

Taveniere: For sure! A lot of it is trying to get the parts right and playing what they really are, but the other side of it is listening to what the live band is actually doing and approaching each situation as its own. I had to buy some new pedals to make it work. Like, I never played slide guitar, so I had to learn to play that and buy a volume pedal to properly play the killer slide guitar parts our friend Tim Presley from the band White Fence added to the album. I had to learn to play some different styles and techniques, and while these parts are fairly simple, it took work to get it all to sit right with the band and learn that different touch.

I also do some things live that double or work in harmony with our sax player [Kyle Forester]. I ask myself what the song is missing and how I can make adjustments and make the right impact. I like to focus on the little details. I think that stuff is important, and if it’s something I want to hear live, it’s something a fan might miss were I to leave it out.

Jeremy, there’s a lot of guitar on this record that is subtle or technically demure, but substantial in function—like the little lead licks on “Sun City Creeps.” How do you go about writing melodies like that?

Earl: I started getting into writing more rhythmic patterns like that from listening to a lot of African highlife and West African palm-wine music. I got obsessed with those rhythms, and that came out in the vibe of that song. We were going for this Ethiopian jazz kind of vibe, so while we were jamming I started riffing on those ideas and that part became almost the hook of the song. Coming from being a drummer and hearing things as a more percussion-minded person, little rhythms really interest me and I gravitate towards them.

What led you to African music?

Earl: Touring and going into record stores on the road. A friend gave me one of the first Éthiopiques compilations, and that sent me down that rabbit hole. I fell in love with those compilations and started picking them up on the road. We’d jam them in the van and we all started digging that sound! The vibe of that music is so intoxicating.

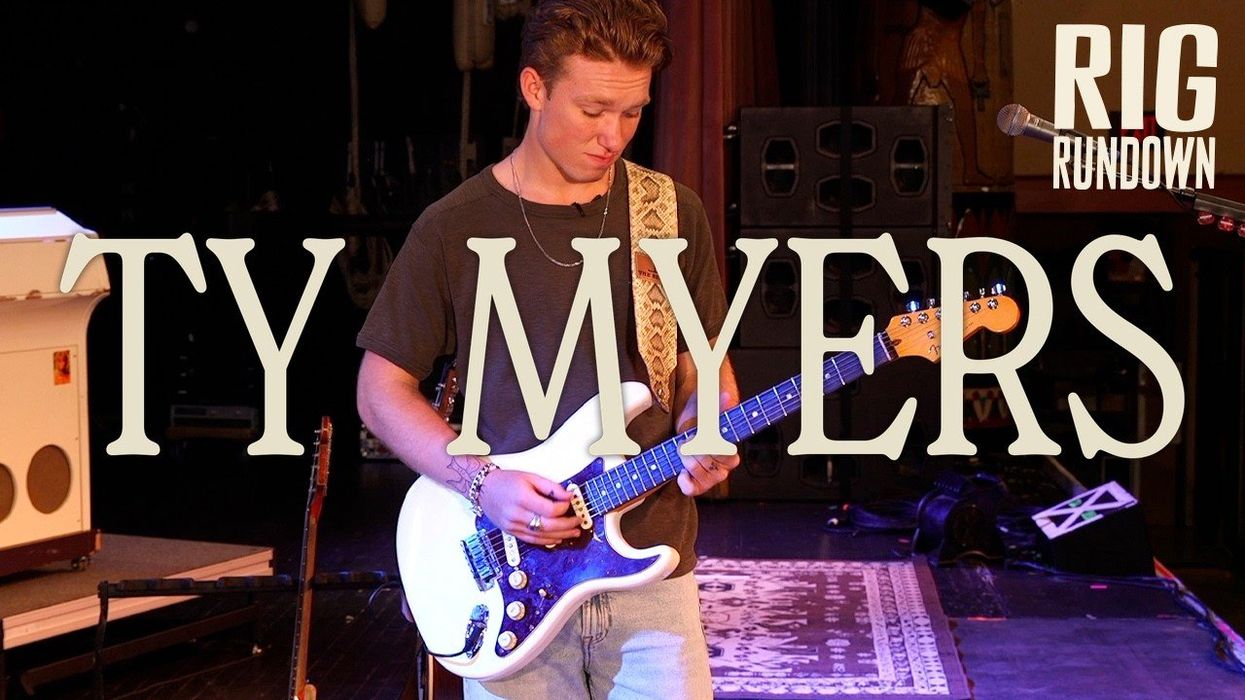

Although he also plays a Phantom Guitarworks Teardrop Hollowbody 12-string, Jarvis Taveniere’s primary live guitar is a 1965 Guild Starfire III with a Bigsby-style vibrato. Photo by Matt Condon

The guitar harmony in the bridge of “Creature Comfort” is another example of a substantial subtlety. How did that part come about?

Jeremy Earl’s Gear

Guitars

• ’60s Silvertone 1451

• 1958 Epiphone Cortez

• 1970s Yamaha FG200

Amps

• ’60s Fender Deluxe Reverb

• ’70s Fender Princeton Reverb

Effects

• Boss RE-20 Space Echo

• 1970s Roland RE-301 Chorus Echo

• Dunlop Cry Baby wah

• HomeBrew Electronics Germania

Strings and Picks

• Ernie Ball Regular Slinkys (.010–.046)

• Dunlop Nylon picks (.73 mm)

Jarvis Taveniere’s Gear

Guitars

• 1965 Guild Starfire III

• Phantom Guitarworks Teardrop Hollowbody 12-string

Basses

• 1978 Fender Precision

Amps

• ’60s Fender Deluxe Reverb

• ’60s Fender Bassman

Effects

• API 512c mic preamp

• Analogman Bi-CompROSSor

• Dunlop Cry Baby wah

• Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail

• Electro-Harmonix Memory Man

• Electro-Harmonix Stereo Pulsar

• HomeBrew Electronics Germania

• Ernie Ball volume pedal

Effects

• La Bella flatwound strings

• Ernie Ball Not Even Slinkys (.012–.056)

• Dunlop Nylon picks (.73 mm)

Earl: The song was completely written in the form in which it appears on the record, and we laid that one down really fast. It was my idea to add a little lead to punctuate things, so I tracked the first lead and it sounded really cool. I think Jarvis suggested adding a harmony to it, which we nailed really quickly. The harmony part that came out immediately is kind of strange and has some quirky weirdness to it, which we really liked. So we got it solid and tracked it, but it was pretty much off-the-cuff and very close to how it came out at first.

So you’re not prone to over-thinking compositions?

Earl: Absolutely. That one in particular was literally written in the overdub stage. I said, “I’m going to try a lead here—hit record,” and came up with it on the spot.

The album has a very open, immediate energy. How much of it was tracked live?

Earl: It was tracked live, for the most part, with drums, bass, and guitar, and then overdubs were added on some tunes. “Can’t See at All” started out with a drum loop that I made and we built upon that, but the rest of the songs had their basic tracks tracked live.

Were the tracks with pedal steel written with that instrument in mind? It feels like the centerpiece on “Morning Light”?

Earl: We wanted to have a pedal steel vibe specifically on a couple of the songs, but we didn’t have anything solid in mind as far as parts go. We knew [avant and trad steeler] Catfish DeLorme well enough to know he could come up with something great quickly, and he happened to be available for one of the days we were in the studio. So, Catfish came over and laid those parts out perfectly. We were all sitting in a room going over ideas and I’d kind of hum something to him and say, “Maybe this kind of vibe.” And he’d do exactly what I was after!

“The Take” has a lot of interesting, vibey guitar work. How was that song mapped out and tracked?

Earl: That started by laying down a big track of percussion—shakers and bongos—and then bass and guitar. The bass is mimicked by a guitar line doing almost the same thing, which is what gives it that weird groove. Then we got very heavy into the overdub zone, and the lead line we started with went far away from what I had envisioned—but it took it to another place and totally made it distinctly a Woods song.

The big lead break and rhythm parts with the wah are very cool. What gear did you use for those sounds?

Earl: That was done with my go-to Silvertone and a wah through a vintage Roland Space Echo and into a Fender Deluxe Reverb and a Fender Princeton, with the reverb and tremolo on the Deluxe cranked up a bit. The amps were tracked in different rooms—one was in an isolated room, and one was in the room with me—so we had options to blend the sounds. That’s one of my favorite guitar sounds.

What’s the story on your Silvertone?

Earl: It’s a ’60s amp-in-case model, the 1451. It’s the solidbody one, and I believe it might have been the last of the amp-in-case models that they made. It’s got one neck pickup and I love it!

Jarvis, the bass tones on the record are killer. Were you using flatwound strings to get that deep, thumping tone?

Taveniere: Yeah! I’ve got a 1978 Fender P bass that I love, and it was strung with those. I remember walking into Main Drag Music in Brooklyn before a tour a few years ago, and I fell in love with this bass—but we were going on the road and I play guitar live, so that wasn’t coming with me. So it went home and just sat in my apartment while I was on tour, but I’m glad I got to use it on this album. I love it. It’s strung with La Bella flats, which are kind of expensive but totally worth it. I’ve had the same set on it since I bought the thing four years ago. I keep expecting to want to change them but I don’t need to. I also used a short-scale Fender Musicmaster that was at the studio on a few tracks, like “I Can’t See at All.” That thing sounded great, too.

Earl: I’m cool with it. I think of their influence on us as more of a spiritual thing. We’re not trying to be anything like them, sonically, but the vibe that they have and put across has always really hit home for me. I just love their concentration on live performance and recording and documenting things. It’s a very special band to me. For us, it’s not about technical playing or anything outside of the vibe and spirit they had. And our songs do change live a bit. On “The Take” we’ve started leaving the ending a little loose, and it’s becoming something of a live staple for us to jam on and explore.

YouTube It

This 2012 performance reveals Woods’ subtle mood-building approach: It’s all voice and melody until nearly five minutes in, when Jeremy Earl launches into a feedback free-fall that finally culminates with him and Jarvis Taveniere chiming their way to the final verse.

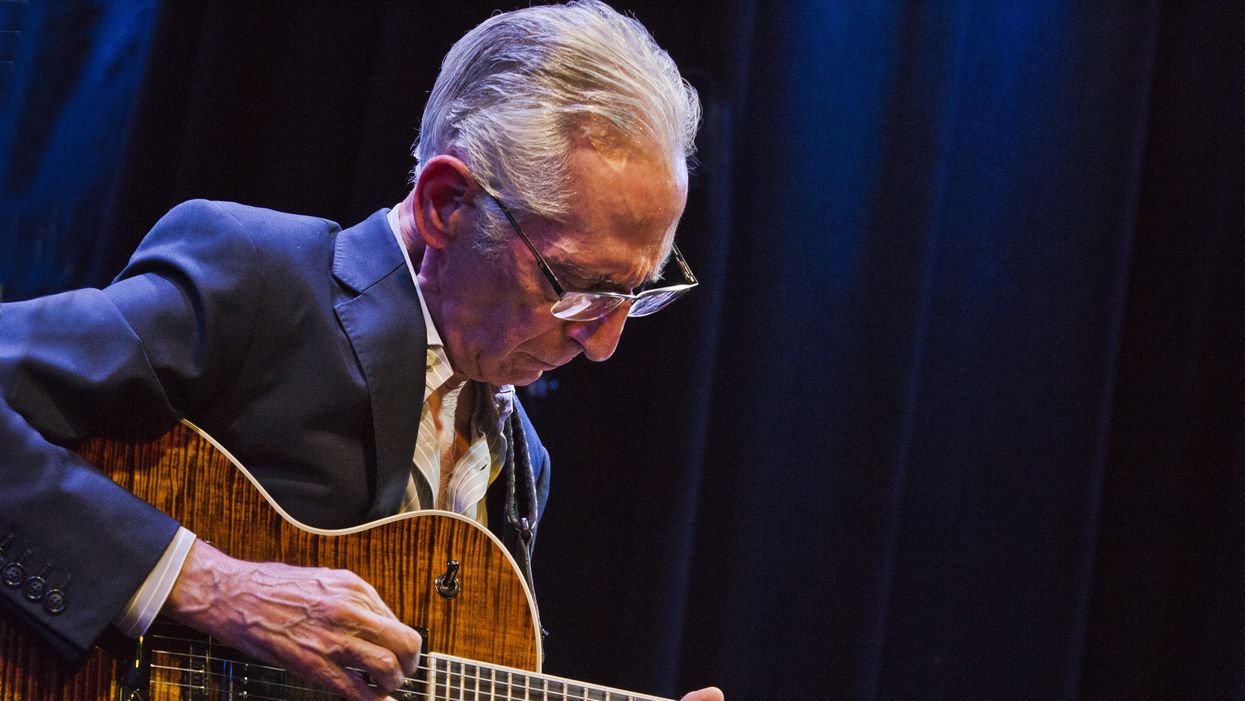

Miller’s Collings runs into a Grace Design ALiX preamp, which helps him fine-tune his EQ and level out pickups with varying output when he switches instruments. For reverb, sometimes he’ll tap the

Miller’s Collings runs into a Grace Design ALiX preamp, which helps him fine-tune his EQ and level out pickups with varying output when he switches instruments. For reverb, sometimes he’ll tap the