“If I had pictures of my heroes on the wall, you’d see Coltrane, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Biggie Smalls, David Bowie, maybe a Zeppelin album, and the Beatles,” guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel says.

Even via a transcontinental Zoom call I could see that his Berlin studio wasn’t a gear museum or memorabilia showcase. It’s a workspace that reflects his myriad influences and his never-ending string of varied projects. And Angels Around, his latest album, was recorded in this space with drummer Greg Hutchinson and bassist Dario Deidda, his gigging trio.

“I’ve always loved trios,” Rosenwinkel mentions. “The trio format is very dear to me and it’s a very intimate setting.” This affection stretches back to his first album as a leader, East Coast Love Affair, which was released in 1996 and recorded live at New York City’s Smalls Jazz Club, which was an incubator for a dynamic and youthful scene that also included pianist Brad Mehldau, saxophonist Mark Turner, and fellow 6-stringer Peter Bernstein. At the time, Smalls was the place to catch the next wave of fiery young improvisers, and East Coast captures Rosenwinkel using a clear, reverb-laden tone that matches perfectly when his gentle falsetto peeks through.

In a way, the album mirrors Angels, yet offers a controlled view of how Rosenwinkel’s playing and composing has matured over the last quarter-century. The crispness of his melodic ideas is there, but the musicality behind them has become more meaningful, which can be attributed to his constant stream of recordings. His tone has lost a bit of attack, by design, but still feels as forceful and direct as it did that night at Smalls.

The idea of doing a live-in-the-studio trio album was interesting not only for musical reasons, but logistical ones, too. “It was easy to do, because you just get in the room and play for a couple of days,” says Rosenwinkel. “Plus, I have ongoing projects that are much more involved.”

Over his shoulder, on the Zoom screen, sits an upright piano, which is demanding his attention for a forthcoming piano-based album. On his music stand sits a chart for “All Is Well,” a recently released track that shows off his more rock-pop side in an obvious nod to his melting pot of influences.

The sound of Rosenwinkel’s guitar, at its core, is full, dark, and pillow-like. His lines flow like water and the trio setting offers space that allows him to explore every inch of the compositions. Both Hutchinson and Deidda push and pull the tunes in new and interesting ways. Check out the syncopated funk-like groove on Monk’s “Ugly Beauty,” for example. Not to mention the bluesy, soulful original, “Simple #2.” And read on for a breakdown of Angels Around, and to learn about his passion for digital guitar technology and his return to fronting a rock group.

At what point did you feel drawn to play as a trio for this album?

After I released Caipi [in 2017], I wanted to get back to more of the common ground of what I do. Plus, the trio really came together in the past few years. I was very happy with the chemistry of the group and everything was clicking. And I love playing with those cats. We had been playing a lot, so it made sense to record. I’m really happy with how it came out.

Have you become more productive recently or is balancing several projects at once typical for you?

Apart from the worry and the financial and health concerns, it’s actually quite nice to have a time-out from the craziness of my life as it normally is and just have unbroken time at home. If you had asked me what my biggest wish was, it would be to just have three months of unbroken time at home. So, this is almost like a dream come true—in the sense that there’s so much that I don’t get to because I’m away. Plus, I’m lucky that I have a studio.

It’s always interesting to hear the stories behind what tunes you choose to record. Did cutting [saxophonist] Joe Henderson’s “Punjab” bring back any memories of playing with him?

I love Joe Henderson’s music and having had the opportunity to play with him was just one of the biggest opportunities that I’ve ever had. I really cherish those memories. I loved those tunes before I got to play with him, and it was incredible to come into the first rehearsal and have him call “Punjab” and “Serenity,” and “Caribbean Fire Dance.” It’s an interesting song with its own arrangement and a lot of nooks and crannies in the composition that make for really interesting interplay with the trio.

What liberties do you feel like you’re able to take with a tune like that when you bring it to the trio?

The more I have a handle on what it is harmonically and structurally, the more I can play it true to itself and the more I feel like I’m not limited. My process is to try to get as deeply into what it is and live there so completely that I just feel so happy to be there finding my own melodies and being able to express my own feelings and instincts within that form.

TIDBIT: All of Angels Around was recorded and mixed in Rosenwinkel’s home studio in Berlin. “It was easy to do, because you just get in the room and play for a couple of days,” says Rosenwinkel.

Do you have a mental checklist that you go down when you’re learning a tune, or is it as simple as playing it repeatedly?

Mostly sitting around and playing it over and over again. Playing it so much that you kind of forget that you’re playing it and you just find all of these places within it. You start discovering things that are unique to the song. I can take one song and play it for three hours, and then connections are made. Then you begin to discover your own relationship with the song and discover your language within the song. I just love these songs. I love to play them, and the more I play them, the more I find other ways to play them. I really enjoy the music of it.

Paul Chambers didn’t write too many tunes. How did you discover “Ease It?”

I discovered it on his album called Go. [Drummer] Jorge Rossy gave me a cassette tape of it when I moved to Barcelona in 1993. I spent about six months living in Barcelona, and I was originally staying at Jorge’s grandmother’s house. I just loved that album. It’s amazing how much great music was recorded and there’s so much to discover even if you’ve discovered so much already.

I hear a lot of Monk in your playing. Do you think he was more of an influence on you as a composer, or as an improviser?

I would say both, because there’s so much composition in his improvising. There’s so much architecture. I love that aspect of music—just the way things are constructed and the concept of economy and that everything has a purpose and there’s nothing that’s superfluous. Even in my style, which I’m developing, that has a lot of notes and contains a lot of information, my goal is still economy and clarity of an idea. I don’t want to waste any note as well.

Listening to Monk is always an inspiration in that regard. His compositions are just so beautiful and the voice leading of his tunes is so inspiring because it’s so tight, in that everything makes so much sense. But at the same time, it’s so interpretable, and because it’s interlocking you can find many, many different ways that it can interlock with other approaches, like substitutions and other pathways that he provides by making the structure so functional.

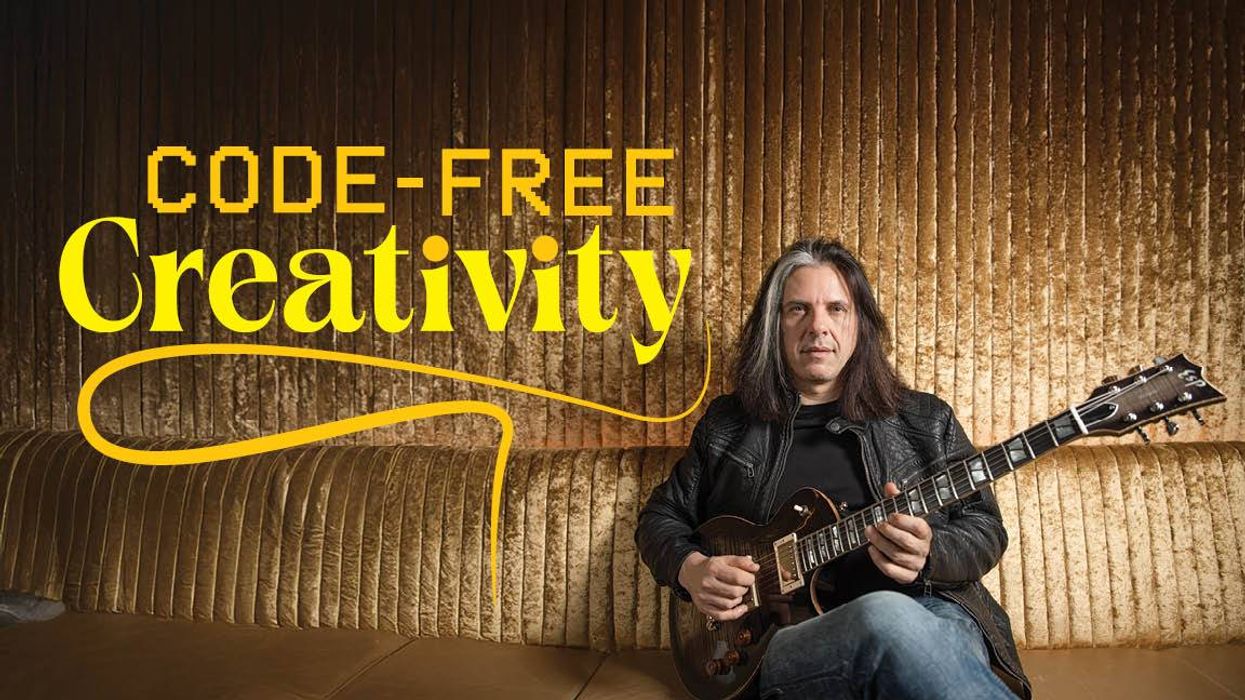

As a composer, Rosenwinkel looks to heroes like pianist Thelonious Monk and bassist Charles Mingus for inspiration: “There’s so much composition in Monk’s improvising. There’s so much architecture. I love that aspect of music, just the way things are constructed and the concept of economy.” Photo by R.R. Jones

It’s so interesting to hear the indie-rock vibe on the intro to “Simple #2.” It’s easy to pick out where those influences came from?

Oh yeah, totally.To me, that section is like [drummer] Elvin [Jones] and [John] Bonham. It’s like Coltrane, but it’s also like Black Sabbath. I grew up on rock and hard rock, and I love British rock and classic rock. It’s definitely a part of me. Bowie is one of my most important influences, and also other kinds of music like hip-hop and rap. Biggie Smalls is a genius and I love to listen to his music. So, there are a lot of sensibilities in the music that come from places that aren’t only jazz. That’s why I love playing with a drummer like Greg. He’s also like that. He loves a lot of different music, so he can feel the subtleties and sometimes disappears between these kinds of moments in different kinds of music. The heaviness of a vamp of the Coltrane quartet can easily parallel a Zeppelin groove.

I’ve read that you’ve been working on a more rock-focused project. What’s the status of that?

Actually, it’s on the front burner. The two things I’m doing right now are a piano album and working on one of the songs that comes from what you’re talking about. I’ve been trying to figure out how to release this album of rock songs. I might just release them one song at a time. I’m gonna release this song called “All is Well,” and we’re just making a video for it now and I’m finishing the mix. That’s definitely in that genre.

What’s the instrumentation? Are you singing on these tunes?

It’s drums, bass, guitar, keyboards, and vocals. I’ve always been singing. I’m often known for singing what I play. People say, “Oh, he wears a hat and sings what he plays.” [Laughs] One time I was in Japan and I saw this kid outside of my concert, and he had a hat just like mine. I saw him in the hallway, and he said, “Hey Kurt! I have a hat just like you and I sing when I play.” [Laughs]

Does it feel different when you’re the frontman singing the lyrics?

It’s totally different. I had to get used to actually performing as a singer, and it definitely took a minute. I used to do it when I was a teenager. All of my songs had lyrics and I had bands that I would do concerts and sing, but then I got into jazz and I stopped doing that. At first, I was really paranoid about it. I got in-ears and I was doing everything I could to help myself with my pitch. Then after a while I began to actually learn some things about the instrument of the voice and my experience grew to the point where I realized a lot of stuff on how to do it. I gradually ditched the earphones and didn’t have a special signal path, and then I’d just get up there with the mic and feel really competent and comfortable. But it is different. One thing I really like about it is that you can express such specific ideas through lyrics, and it’s really liberating to have the meanings of the music be overt instead of hidden. I can conjure up a lot more imagery and say things that were previously hidden in the music.

You mentioned that when you were younger your songs had lyrics. Has writing lyrics and poetry remained a creative outlet for you?

Yes. I’ve been writing in journals since I was 15, and I’ve kept them all. There are thousands of pages of stuff that I’ve written. Actually, another project I have is a collection of poems, reflections, essays, and dreams from my journals that I’ve been compiling. I’m taking the stuff I think is worth reading and I’m wanting to make a book with that material.

From when I was 16 to 22, I considered myself a writer more than anything else. I was living in a way that was inspired by writers more than musicians. My friend Bill Hangley, who is an excellent writer, is helping me with this project, and one of the things that we’ve decided to do is to start a Twitter account called yesterkurt, which is curated excerpts from my journals. I have nothing to do with it in terms of selecting and posting. I have no idea what they’re gonna do. I’m kind of amazed that these journals have stayed with me for so long. They’ve survived every move since I was 15.

Did this habit of journaling spill over into your musical practice?

Yeah. There are some things that are music related. A lot of it has to do with chronicling my growth and my desires of where I’m at in music and what lessons I'm learning. They have a lot to do with life lessons. It’s a chronicling of a person’s development through life and through music. There’s a lot of expression of where I would like to be and a lot of analysis of where I am and how that’s working.

Is a memoir somewhere on the to-do list?

Yeah, I’ve already started to write down the key words of all the little episodes that I want to include in it. That’s also something I’ve been thinking about actively in the past year.

I see you have an Axe-Fx in your studio, and when I saw you last year you had a pretty involved Helix rig. It looks like you are not afraid to eschew glowing glass tubes.

Yeah, my adventure through amplification as a touring musician started with playing Polytone amplifiers. During this really sweet spot in the ’90s, I was able to put a certain Polytone bass amp on my rider and get that amp everywhere I went. Polytone amps became so popular and successful that Polytone decided to streamline their production and cut costs in many different ways that had the effect of having their amps widely available, but they didn’t sound as good. The next most available amp was a Fender Twin Reverb, so I migrated to that. I never really liked it all that much because I would always have the treble at zero. It was always a negotiation with a Twin Reverb to try and get the sound I was hearing in my head.

So, you’re bouncing between the Polytone and Fender Twin on the road, but when you’re at home what is your amp of choice?

I have in my house an old Polytone, an old Twin, and a new Twin. I don’t want to get a really incredible amplifier and be really happy at home and then go out and, you know, cry after every gig. [Laughs] I’d rather work with what’s available in the world on the gig, and when I’m home do as much R&D as I need to try to get the sound closer to the sound I have in my head. It’s all about consistency for a touring musician who relies on the backline, you know. I used to be able to fly with my Polytone in a flight case.

When did you start to move to digital amps and effects?

Yeah, you know, with the digital revolution in amplification, Line 6 was the first and it was not so happening. Then Axe-Fx came along and they’ve just made leaps and bounds. I’ve been on board with every iteration of all this stuff. It’s just like video games. I’m a ’70s kid, and we had the first Pong Atari games and every iteration all through the development of video games.

Guitars

Yamaha SG200

Amps & Effects

Fractal Audio Axe-Fx III

Electro-Harmonix POG2

Electro-Harmonix HOG2

Boss OC-3 Super Octave

Electro-Harmonix Mel9

Vintage ProCo RAT

Strings & Picks

D’Addarios (.010–.046)

Dunlop 207s

Where do you start when you develop a preset?

I’ll usually start with a Fender Twin. The thing that’s really cool about the Axe-Fx is that you can tweak parameters that aren’t available on the actual amp. You can change the tube type, the sag, or how the power supply works. All of the variations that you find when you go from one gig to the next is gone. They could all say Fender Twin Reverb, but one of them is really fast and soft; the other one’s really hard and tough and slow. Maybe one of them feels really glassy with a big low bottom, and the other one feels really focused in the mids, and another feels like when you play a note it’s just like escaping from the speaker at the speed of sound. Another amp might feel like you play a note and it just is kind of getting sucked back inside of the cabinet. All of these things are aspects of the amp that you deal with when it’s happening in real life that you don’t have any control over. But if you go into the Axe-Fx, you can tweak all these parameters so that it responds exactly the way I want it to. I love that.

You obviously aren’t intimidated by endless menus and editing. Some guitarists’ eyes just glaze over.

Sure. I’m susceptible to that, too. One thing that’s great about the new Axe-Fx is that it has a very large LCD color display and it’s very well laid out. You don’t really have to go that deep into menus. There’s a lot of visual feedback and interesting things to look at while you’re tweaking, so that it’s not just like parameter name and parameter value. But it’ll show you some interacting between things, like a threshold on a compressor or something like that. I feel like they’ve really improved the user interface from the last model to the new model.

Can you give me an idea of what your typical signal chain would be?

I can show you, actually. It’s pretty complicated [laughs], but basically what happens is the guitar goes in and then it’s sent to this [EHX]POG2 and then it comes back. That’s the basic signal path. [Kurt is showing the signal flow layout on his Axe-Fx III.] It goes to the amp cab, then you’ve got a gate and an EQ. After that it’s sent to two delays in parallel and then a little looper—I hardly ever use that. And then it goes to a reverb, a compressor, and then goes out. There’s some distortion, but there’s a lot of compression going on. There’s also a compressor in the amp that’s being used. It then gets split off and it goes to this Electro-Harmonix HOG, which I use for the freeze effect so I can hold chords. Next, it goes into this Boss OC-3 Super Octave that allows you to only effect the bass notes and not the top of the chord. And then I’m also going into this [Electro-Harmonix] MEL9, which I sometimes use for an extra quality, where I might blend Mellotron flutes in with the guitar.

You dial quite a bit of attack out of your sound. Do you do that with the POG2?

Yeah. I shave a little bit of attack off, because I don’t like the sound of the pick. It’s not exactly that I don’t like attack. It’s more that I want to be able to shape what that transient sounds like. There are lots of things that go into it. Before I was using this technological solution, it was about what kind of pick you’re using, and I would use those really heavy black Dunlop 207 ones that were really soft on the attack. And I would use heavy strings so that the attack wasn’t thin. It was a bigger sound. I’ve worked for decades on trying to achieve that sound. This way is still imperfect, but I’m probably closer to the sound that I have in my head than I’ve ever been, which is really exciting—to be able to express the way I want to express and also have the guitar respond the way I want it to.

Are you still using heavy strings?

No. I can’t even believe it, but I’m using .010s [laughs].

It seems like there’s a movement to move back to lighter strings.

Holdsworth used .009s, and I remember playing his guitar one time backstage and it was like you just blow on it and there’s a note. I’ve discovered that if the guitar is good, then you can use a lighter gauge and still get a big tone. In jazz it comes from the big jazz boxes and the history of not even having amplification. I used to play .013s and felt like I couldn’t play without them. [Laughs] I think the better your technique is, the more you’re able to deal with lighter strings, because every little nuance that you do is just slight movements and the expressiveness is much greater.

The spotlight’s on Rosenwinkel as an improvisor in this solo performance from the Montreux Jazz Festival, where he elaborates on the classic “Stella By Starlight” with some help from one of his core effects, the Electro-Harmonic Harmonic Octave Generator.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)