| More Huff Click here to read Part 2: On Studio Preparedness and Recording Tips |

Guitarists, however, know Huff for more than his award-winning skills behind the board. They know him as the consummate musician: a studio veteran who literally played on at least one track by almost every recording artist in the 1980s, as well as most of Nashville’s releases in the 1990s. They also know him as co-founder of the rock band Giant, with his brother David on drums.

Versed in every element of his instrument, yet claiming little technical knowledge, blessed with an innate ability to adapt to any genre, a player who understands that less is sometimes more, Huff is what’s known as a guitarist’s guitarist. It’s a simplified term but rich in meaning.

Dann Huff’s success as a musician and producer is, of course, the result of his talent, but being a down-to-earth nice guy has certainly played a role in why artists keep coming back. “If being a great producer means being an ass,” he remarked in a 2000 interview, “I’d rather be second rate.”

In the first installment of this interview, Huff discusses Keith Urban’s guitar work on Defying Gravity, how he defines his role as a producer, and the pros and cons of plug-ins and effects.

How has your approach to working with particular artists changed over the years?

In eight or nine months it was a rush to get three projects done: Keith Urban [Defying Gravity], Rascal Flatts [Unstoppable] and Martina McBride [Shine], all three with release dates within a week of each other, not by my design. It sounds so simple now, but in the middle of it I thought I’d go crazy. It’s not just making music these days. It’s schedules and expectations. They didn’t give me that chapter in the producer’s handbook when I got into this side of the business!

This was my third or fourth record with each of them. Rascal Flatts, for example—I mentioned expectations. They want that string of hits to keep going. Number One is a priority on everyone’s list. Then you look for musical growth and musical consistency, which can play against that growth. They systematically search for sweet spots in radio hits. Their guitarist, Joe Don Rooney, wasn’t playing much on the records when that band started. Now there’s maturity in his solos. We look for tone differences, nuances in his playing, not for flash. The same with their bass player, Jay DeMarcus. It’s harder to measure growth when you’ve been doing it for that long. From a first to a second album it’s easy to see. You look for a certain maturity that’s not apparent to the average listener, but musicians can sense it. In the choice of material, when they write, you’re always looking for different ways to say it, as opposed to an artist like Prince, who morphs into something new and different every time. Those folks are rare and far between. Also, you take a lot of risks with that, and in this day, in this business, people are less willing to take risks because they want to fill arenas, so the growth is less.

Dann and Keith show off their #1 plaques at Keith Urban's "Sweet Thing" No. 1 Party. Photo: Ed Rode |

I supposed it could be the case, but not so far with us because they’re self-effacing and so demanding from their standpoint, so there is always an edge in that situation. Keith and I are very close friends, but on a musical basis we always have a bit of friction. We joke about it and put it in the Lennon/McCartney syndrome, not comparing ourselves creatively, but the idiosyncrasies in our personalities. Lennon was an acrid, tough person who would say something in a tight, more cutting-edge way, and McCartney was a real musician who was always about melody and pop and seemingly fluff, but when you dive into them historically that’s not always the case. What I hate is that Keith always gets to be Lennon! Then he’ll jump into the other side of his personality because he adores pop, and I say with love that he adores the craft of it. One day I say, “I don’t need that,” and the next day he says, “Don’t put that shit on this track!” We tug at each other, and in some ways there’s more friction now because we know each other, and our sensitivities as people make us more vulnerable.

Will he ever make a guitar album?

I don’t see it in the cards. I asked him and he says he has no interest in it. That interests me about working with him, too. He can’t divorce being a singer, songwriter and musician. He’s a performer. In the studio he doesn’t just lay down tracks. He performs them. He’s communicating the song structure. If there’s no demo, he grabs an acoustic guitar, plays it, performs and doesn’t think about the guitar solo. It serves the song and emotion of what he tries to say, and when he lays down vocal tracks he has an acoustic guitar in the booth with him. He doesn’t bring in instrumental records when we listen to music together. He’ll listen to Pink Floyd, and songs with instrumental integrity, but always with a lyric. He’s grown more as a guitar player in the last two years than I can measure. When I hear his recorded solos they’re not spellbinding, but when you listen to what he says with the guitar, the growth is there, the voice is there, and I take a lot of joy from that in making our records.

Is there a track on Defying Gravity that defines Keith as a guitarist?

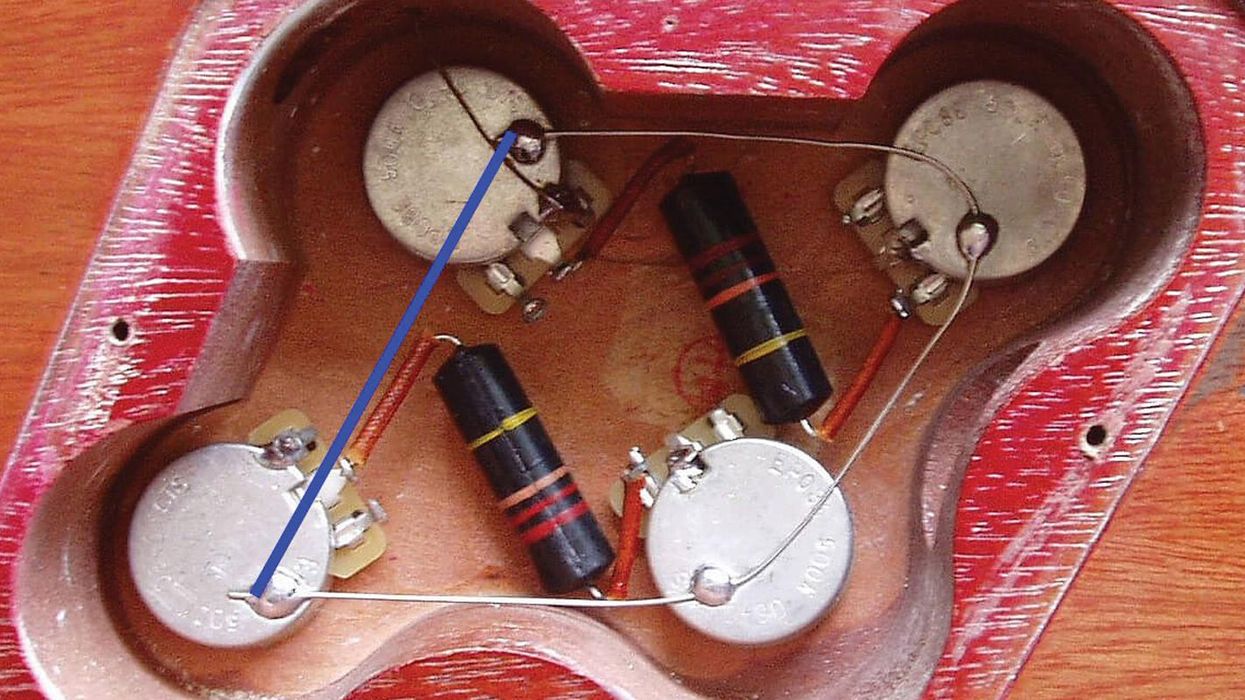

Keith used to be my brother in the sense that we didn’t care which guitar, whether it’s a cheap guitar—he’s one of the only people who knew less about guitars than me. To me, playing guitar is different in a lot of ways from knowing the history and making of guitars. I have friends who can almost tell you the serial number on a guitar. For me, it was never an interest. If it played good and I liked the tone, that meant it was a good guitar for me. If somebody told me it was a ’63, I would know that and that’s it. Keith... some switch kicked in, and my brother, who was as in the dark as I was, became enlightened and left me in the dust. [People who collect guitars] will have a ’59 Les Paul to show at their house and a copy onstage. Keith plays them onstage! He has educated himself and absolutely destroyed that side of our friendship! He brings in some of the most gorgeous guitars. So it’s plug in and see how it sounds, and an irreverence that keeps it fresh with him.

“If Ever I Could Love,” on the new record, is not a big “guitarist” song, but if you dissect the parts on this thing, the layers of guitars on it … I remember from the mix. We started tracking at Justin Niebank’s house with a drum machine, and Keith was using a [Gibson] Melody Maker or a Tele through a teeny combo amp, a 20-watt Marshall. We built a Mark Knopfler-type riff and a five-minute song that starts out with a drum machine and guitar ends up with half the world on it. The solo sound reminds me of almost a Queen-type sound, steeped in ’70s-sounding guitars. It’s a real defining guitar song for Keith. There’s nothing on it chops-wise that any young guitarists would say, “I can’t do that.” It’s very accessible. But I grab his guitars and play the same parts and it sounds totally different. So much of who he is comes from his fingers, from a rhythmic, textural and musical standpoint.

One that’s defining in another way, “Til Summer Comes Around,” has a beautiful solo, very spacious; the solo is deceptively simple, but with a Beck-type personality. The way we work is very stream of consciousness. Everything is built on something else. We used every conceivable amp—some vintage, one Fender Blues Junior, and once a $200 Keeley stompbox compressor. It was his guitar tech’s 10-year-old son’s and it became the sound for the day just because it was there. We don’t have an arsenal. It would be easier if we did, but it wouldn’t be us. Our path is more disjointed, but it always gets us there.

Is Blackbird your primary recording studio?

I can do 90 percent of an album at Blackbird, but it’s small for tracking. I rarely venture out from that studio. Blackbird is a musical playground. John and Martina McBride—their passion has always been recording. John has done well with his sound company. He’s one of the biggest live mixers; he used to do Garth Brooks when he was touring, and he’s content to put everything into this. It’s now a complex that everyone on this side of the Mississippi comes to. It’s not just the physical rooms but also his mic and gear collections—pro audio, guitars, drums, bass. He’s a serious collector. They’re not in humidity-controlled rooms to look at. He has them on the walls, and the availability of acoustic and electric guitars is beyond anything ever done in the recording business. He called me five or six years ago and asked, “Would you work in my place if I built you a room?” It was a field of dreams! He’s got a who’s who in there on any day. With Keith’s record we tracked at the Castle in Franklin (TN). I’ve recorded there since I was 18 or 19. Then we overdubbed and mixed at Blackbird.

When was the last time you recorded in analog?

Probably three years ago, I think with Keith. We tried to go back in a way. It was interesting. We loved it, but it didn’t make the music better. It was a fun drill, like going back to the days of yore. We all prefer the sound of records back then, but this MP3-crazy world we live in, the speed with which people want records, it’s not the easiest way to get from Point A to Point B. Engineers are so good that I’m not sure it’s worth the time and expense of working in analog anymore, at least in the records I’m making.

What is your definition of a producer?

Just an enabler, basically. Hopefully, you’re a creative partner—and a transparent partner—in the life of a project. The definition, for me, is someone who takes the vision, dreams and wishes of an artist and helps them get to that point. Helps, not does it for them or sits back while they do it. It changes from project to project because the needs are different. I always pray that people don’t say, “That’s a Dann Huff record.” I’ve been described usually in a way I can deal with, the quality of it, but I don’t have a defined methodology because one size doesn’t fit all, even with the same artist. Honestly, I’m still defining it as I go. My answer next year won’t be the same as it is now. I’m building on a train of thought that it’s 100 percent interactive. That’s where collaboration enters into it. You learn to listen and never arrive. I’m always learning new ways to listen, suggest, maneuver and gently nudge the artists to find new ways to say what they want to say. Or sometimes I just change guitar strings for them. It’s an intense time when people put down musical thoughts that will represent them for the next year or two. I move on to the next project, but this is their life and how they are judged and it’s a building block for their career. Sometimes it’s just talking about what somebody is going through, being a friend. We do a lot of that. Enabling somebody to be at their best. It’s coaching, and coaches come in all sizes and shapes. I’ve known producers who aren’t great musicians. It helps, but you don’t have to be, and sometimes it doesn’t help. Sometimes it handicaps you as you look through a different lens. I try to get away from my musical skin to be an effective producer.

How has technology changed the way you make records?

It’s not like it was five years ago. I usually don’t endorse things. I prefer to buy and not be beholden to a company. I don’t use stuff because I get it free. Several engineer friends are flabbergasted at the guitar parts I bring in thanks to the DAW and plug-ins. All I have to do is plug in and do it, and they’re shocked because they hear it for what it is, not for a direct recording process. These are discerning ears, so if they don’t hear the difference …. This virtual guitar stuff sits in the track differently. The new POD Farm has a list of effects, twenty distortion pedals, ten delays; they’ve gotten so good at modeling these things. Ultimately, my favorite lesson about sound came from my hero, Mutt Lange, the greatest producer of all time. I didn’t do this on purpose, but I modeled my take on sound from him. I worked with him a lot as a guitar player, and whatever was there, you used. He’s used Rockmans on massive records and you’d never know. He says there is no bad sound—turn it up and it becomes greater sound! All sound is usable. The trick is how you use it.

The effects are easier to achieve, but at what price to creativity?

Not at any price. I look at it in two ways. The biggest problem with technological breakthroughs is that you have limitless options. You fight against learning to make a decision, and that’s the toughest thing these days. With limited technology you spent a lot of time trying to come up with guitar effects, amps, all kinds of stuff, at the price of losing the moment. Now you can store the sound. With the click of a mouse you’re back to it and can immediately move on to what you’re trying to create. If the Beatles had had all this, they would have used it, and we worship the music they made with limited technological advances. Part of their genius was being able to see limitations. All the guitars and amps we’re reverent about are what they used, which were shiny new guitars and amps right from the store. There was no reference for them. They grabbed guitars, strung them, turned on the amps and there their minds went. Nowadays we’re inundated and overwhelmed with options and we forget what we’re trying to say. It’s a blessing and a curse. I’m curious about the next round of technology. There’s a lot of new stuff out there, but I don’t think a lot of it really matters.

How important is it for a musician to explore different genres?

All music is the same language, and being exposed to it helps you express yourself better. I have three kids, and Elliott, my 14-year-old son, is the instrumentalist. He’s a drummer and he’s really good; he has that thing, whatever that thing is. They have more at their disposal because of YouTube, which is an incredible tool. They can see things we never could see. He has all of his music and we talk about older drummers. I want him exposed to those musicians, and he’s not going to know about them unless his old man tells him. We saw Steve Gadd do a symposium on the groove, and he learned on the spot. He jams a ton with his friends—we have a noisy house. Kids these days have way more distractions than any preceding generation, an insatiable appetite to be entertained, and instant access at all times. Trying to focus on one thing is the hardest thing for any young musician. They can be exposed to everything at every moment of every day. The greatest musical university is in your home, if you have internet access. Will they redefine music? We’ll see. I don’t know. We’re all too close to it.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

The Allparts team at their Houston warehouse, with Dean Herman in the front row, second from right.Photo by Enrique Rodriguez

The Allparts team at their Houston warehouse, with Dean Herman in the front row, second from right.Photo by Enrique Rodriguez