David Rorick, better known as Dave Roe, still isn’t sure how he got here. It’s been about 43 years since he left Hawaii and moved to Nashville to work as a bassist. He didn’t have any training or remarkable expertise—just enthusiasm, a work ethic, and a love for the open road. Over the next four decades, Roe parlayed those qualities into a legendary career, playing with some of the world’s greatest folk, Americana, blues, and country music stars.

On a Tuesday morning in early May, while taking a break from mowing the lawn of his home just outside Nashville, Roe almost sounds puzzled retracing his steps: touring and recording with Johnny Cash and Charlie Louvin, backing up Dwight Yoakam and Loretta Lynn, working as the in-house bassist for Dan Auerbach’s Easy Eye Sound and as a coveted hired-gun session musician and mainstay in the Nashville gig circuit. “A jack-of-all-trades and an expert at none,” he quips.

That aside, Roe’s self-taught and intuitive upbringing on bass have made him a stylistic chameleon, with perhaps a deeper connection to the rhythms and feel of each genre he plays. His playing evidences a seamless quilting-together of his teachers—’50s, ’60s, and ’70s radio-pop sweetness, the swagger of his mother’s country records, the calm confidence of West Coast Americana, the flair and bravado of funk and disco. His bass parts are classic and unimpeachable, witness marks of a player who learned, with his body and spirit alongside his brain, how to play the bass in a way that people will want to hear.

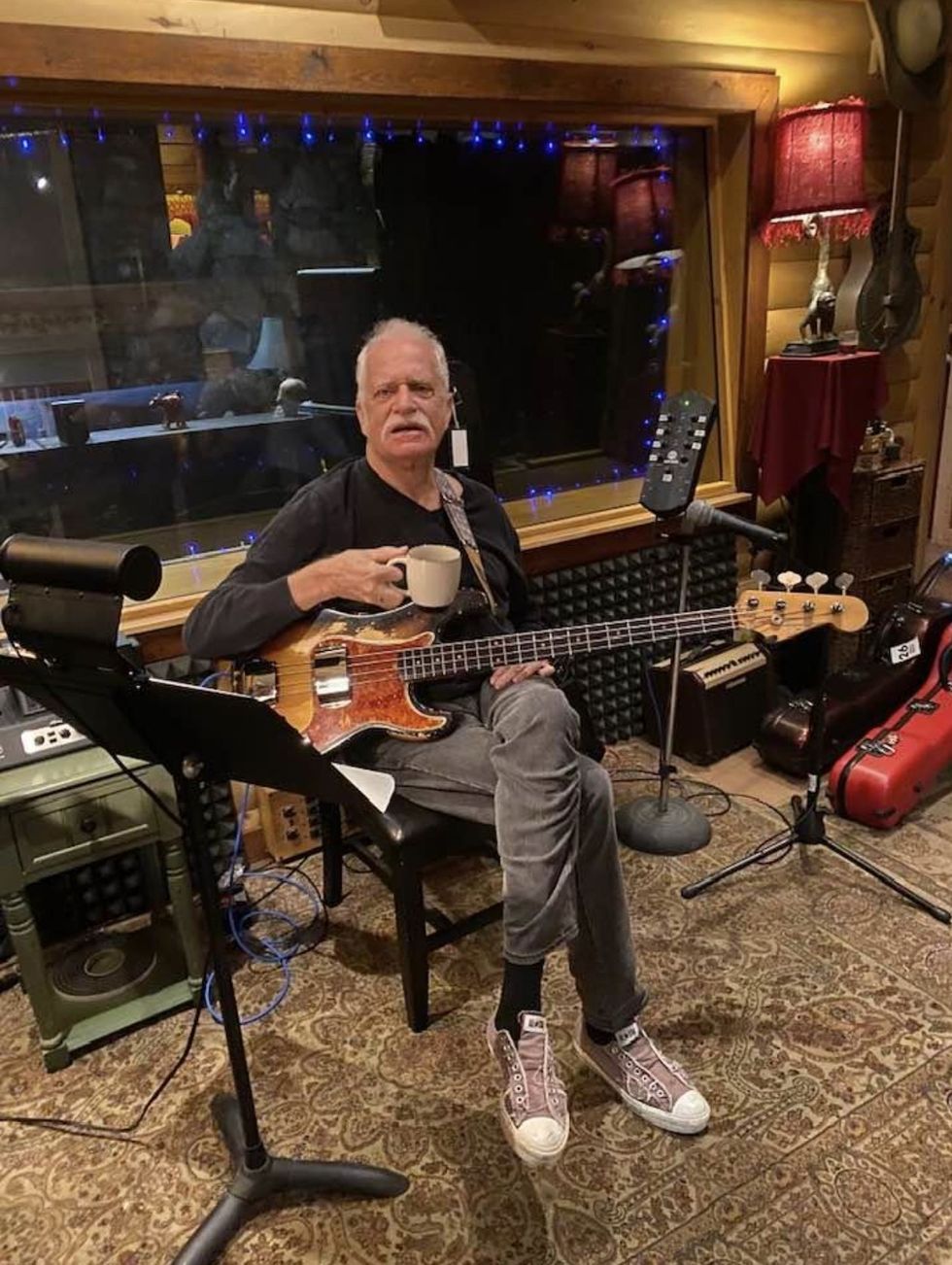

Dave Roe lays down a track at his Nashville Home Studio, which he named Seven Deadly Sins.

Photo courtesy of Dave Roe

Roe’s path from cover-band grinder in island tourist bars to one of the country’s most sought-after bass players might not make technical sense on paper. Thousands of others have started out the same way and never advanced beyond their hometowns. It doesn’t fit into the tidy algorithmic churn of modern life. But music isn’t about algorithms and optimization—not all of it, not yet. It’s still about feel and soul and heart, and a bit of luck.

Roe’s father was a military man, whose service eventually took him and his family to the middle of the Pacific Ocean. He was stationed in a small town called Ewa Beach about 40 miles outside of Honolulu on Hawaii’s third-largest island, Oahu. This is where Roe grew up. He was a drummer before he ever picked up a bass, but in high school, without any local bass players, Roe’s friends elected him to take up the instrument. His first bass wasn’t a bass at all: It was a 6-string Silvertone electric guitar, which Roe restrung with bass strings. “That didn’t last very long,” he says.

Roe didn’t have the money to buy a proper bass, so in 1969, his high-school sweetheart’s father went with him to a music store in Honolulu and signed for a Fender Jazz Bass and an old Guild amp for Roe. “That’s when I got my first really good gear,” he remembers.

Getting a real bass was one thing. Learning to play it was another. And Roe did it all himself—he’s still never taken a single formal lesson. “I sat down with records and taught myself,” he says. “I was a big Top 40 enthusiast. I loved anything that was on the radio.” That included the usual suspects: Jimi Hendrix, the Beatles, Cream, the Rolling Stones. “That’s really where I cut my teeth,” Roe continues, “just playing the blues and hippie rock and stuff like that.” Roe’s first band, a power trio playing covers by Chuck Berry and other early rock ’n’ roll pioneers, worked its way up to opening for Grand Funk Railroad in Honolulu.

Roe rips it up with guitarist Chris Casello at Robert’s Western World on Nashville’s Broadway entertainment strip.

Photo by Elise Casello

Roe moved east off Oahu to Maui in 1971 and joined a country outfit at a critical moment. Due to its relative proximity, the West Coast scene had an outsized impact on the island’s cultural imports, and once the hippie-country and Laurel Canyon folk waves swept over California in the late ’60s and early ’70s, it didn’t take long for it to reach Roe’s radio. His mother was a country fan and imparted some early affection for the genre, and, later, Roe would catch Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and the Burrito Brothers when they toured Hawaii.

Roe didn’t sit still for long. After the country stint, he moved back to downtown Honolulu and played in a rhythm and blues band. In the mid ’70s, he went through a “real heavy” disco and funk phase, and dabbled in prog rock and jazz, too. “I was a working Top 40 musician,” says Roe. “When you work in a tourist town, you have to learn how to play a bunch of different stuff.” His learning technique was the same as ever: “I just would listen and play and try to pick up stuff and copy people. That’s all I did.”

But by the final years of that decade, the magic feeling was getting harder to find. There weren’t enough opportunities to create and live on playing original music, and after a decade of playing covers for tourists, it was time for something new. He settled on Nashville. “I just put my socks in a bag and took off,” says Roe.

Luckily, Roe had an insider in Music City. His cousin, a comedian and professional entertainer, lived in Nashville and let Roe crash with him when he arrived. More than that, he set Roe up with his first gig. His cousin knew folks at the Grand Ole Opry, and took Roe along to a show one evening. Roe was introduced to country artist Charlie Louvin that night, and as fate would have it, Louvin was looking for a bassist. Roe expected to be asked to audition, but Louvin simply told him when the bus was leaving for the tour. “That was a really good gig at the time, a highly respected gig,” says Roe. “That was really beneficial to me.”

Dave Roe's Gear

Roe gets ready for a take, with one of his Fender electrics along for the session.

Photo courtesy of Dave Roe

Basses

- 1964 Fender Jazz Bass

- Alien Audio 5-string bass

- Lemur Music Jupiter upright bass (in studio)

- Blast Cult upright bass (live)

Amps

- Ampeg B4 Head and 410 Cabinet

Strings

- Dunlop .045–.105 flatwound strings for electric

- Pirastro Evah’s for upright

It can be hard to tell sometimes when a moment is the beginning of something, or if it started even before. Both things can be true, but playing with Louvin certainly seems like a critical moment in Roe’s career. After playing with Louvin for three months, Roe was recommended to Jerry Reed, who hired him for his live band. He says gigging with Reed and his band took things to another level. Reed’s musicians, including Kerry Marx and the Blackmon Brothers, were aces, and playing alongside them meant Roe was, too.

Roe says from then on, his career had “a movement to it.” After working with Reed, he joined Chet Atkins for a short stint (“It doesn’t even feel like I was really there,” he admits), and for the next 20 years, he worked the road with a rotating cast of country greats: Mel Tillis, Dottie West, Vince Gill, and Faith Hill all tapped Roe for touring. By the early ’90s, he’d begun doing session work in addition to touring gigs.

Roe was on a break from touring with Vern Gosdin in 1992 when he got a phone call at home that changed his life. On the other end of the line was an unmistakable voice. It was Johnny Cash. Cash’s publicist had jammed with Roe around town and mentioned him to Cash, who wanted Roe to play with him. “He just said, ‘I want you to come and play in my band, and you’re gonna have to play upright bass,’” recalls Roe, who accepted immediately. There was one problem: He had never played upright bass.

“I think it was sort of understood that I would know the style, but I didn’t,” laughs Roe. He did what he’d always done. He figured it out on his own. He borrowed an upright bass and started to teach himself the slap-bass rhythms and plucking styles of Cash’s rockabilly-leaning repertoire. “I had to pull my bootstraps up and get after it,” Roe chuckles. As that first call was winding down, Roe told Cash that he’d see him at rehearsal. “He said, ‘Well, we don’t really rehearse,’” says Roe. “Then I said, ‘I guess I’ll see you at soundcheck.’ He goes, ‘I really don’t do soundchecks, either, so I’ll just see you there.’”

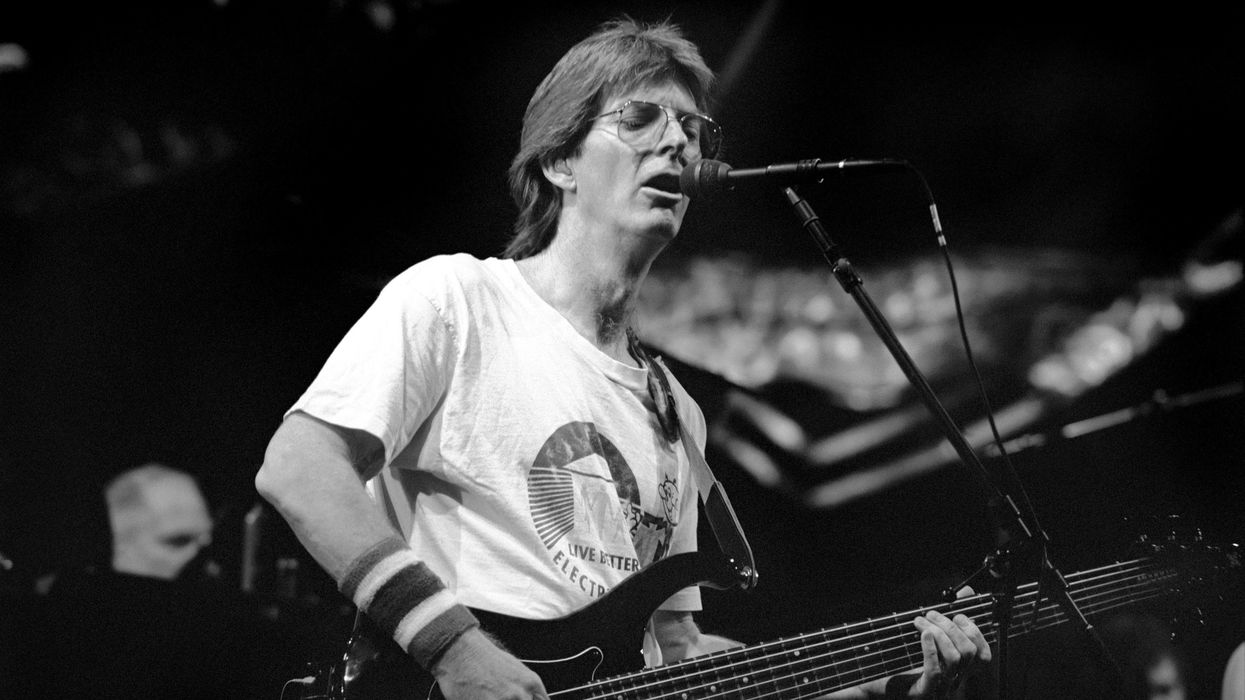

Roe was encouraged to play the upright bass by a call from none other than Johnny Cash. Here, he cuts a track at Dan Auerbach’s Easy Eye Sound studio in Nashville. He is a frequent contributor to Auerbach-produced albums, including Auerbach’s own Waiting on a Song and the Pretenders’ Alone.

Photo courtesy of Dave Roe

Roe describes the first gig with Cash, around a week later in Charleston, West Virginia, as “completely flying by the seat of my pants, with my ear. I didn’t feel good at all. I just felt like I wasn’t the right guy.” But Roe kept working at it. He credits Cash with giving him a shot even though he wasn’t experienced. “He was very patient with me, and the rest of the guys in the band helped me along to develop that style,” says Roe. “There were other guys here [in Nashville] that were already doing that [style]. They could have easily got them. I can’t tell you to this day why they hung in there with me, but they did.”

Roe played bass with Cash until the Man in Black’s retirement from live performances in the late ’90s, and did session work on the singer’s intimate American records. For the first of the series, 1994’s American Recordings, Roe joined Cash and producer Rick Rubin to rehearse and feel out the songs before Cash ultimately recorded them solo. They practiced and recorded at Cash’s cabin studio near Hendersonville, Tennessee, and Roe joined them later when they did overdubs at Rubin’s Hollywood studio. The working relationship was one of the most profound and important of Roe’s career. “Johnny was sort of a Buddha to me, man,” says Roe. “He’s the nicest man I’ve ever had in my life. I learned a lot.”

Working with Cash marked another important transition period for Roe. Back in those days, he says, a professional musician moved to Nashville with the understanding that they’d work the road until they could land a studio gig and settle in one spot for a while. For Roe, that happened after he was hired by Cash and country singer Dwight Yoakam, with whom Roe played for four years. Given Yoakam’s and Cash’s high profiles and the proportionate pay for their musicians, Roe had more time to himself and less need to get back out on the road for another paycheck. Not that he didn’t like the road, though. “To be honest with you, if I had been offered another good road gig, I probably would’ve taken it,” says Roe. “But it just worked out this way.”

Dave Roe and his frequent collaborator Kenny Vaughan at Dee’s Country Cocktail Lounge in Madison, Tennessee, with their band, the SloBeats.

Photo courtesy of Dave Roe

Full-time session work required yet another pivot. Studio players in the city communicated and played with the Nashville Number System, a method of transcribing music by denoting the scale degree on which a chord is built, and thanks to his time in Hawaii, Roe was prepared. Some of the older jazz players back home had introduced him to the system when he was starting out, so he hit the ground running.

Roe spent the next 10 years doing session work and around-town gigs when his next “big break” came. The Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach called him up in 2015 and asked Roe to join a crew of veterans to back him up on his Easy Eye Sound recordings. It turned out that Cash’s engineer, Dave Ferguson, had recommended Roe to Auerbach. Roe became part of Auerbach’s in-house band at his downtown Nashville studio, where he got to work with a lot of the “old-timers”—like Bobby Woods, Russ Pahl, and Billy Sanford. Before long, though, he had joined their ranks. “I’m an old-timer now,” he laughs. And Roe considers his performance on Auerbach’s “Shine on Me,” from the Waiting on a Song album, among his best recorded performances.

Like most musicians, Roe has spent the last few years off the road. He’s focused on demo and custom tracks via work at his own studio, Seven Deadly Sins, and remote collaborations on platforms like AirGigs. He played on Brian Setzer’s 2021 solo record, Gotta Have The Rumble, and his long-time Nashville outfit the SloBeats, with guitarist Kenny Vaughan and Average White Band drummer Pete Abbott, is stirring from its hiatus. His son, drummer Jerry Roe, has worked his way into becoming a coveted Nashville session player. The apple didn’t fall far.

Like all great Nashville session bass players, Roe has the ability to learn tunes and adapt to different styles quickly, whether it’s blues, rock, country, R&B, or even improvised music.

Photo by Anthony Scarlati

Thinking back on his career, Roe is quiet, almost confused, like it’s all a dream he’s just woken up from. “I find myself always being in a state of awe, you know?” says Roe. He’s toured the world and made friends with the biggest names in American music. (He names CeeLo Green—whose track “Lead Me” is one of Roe’s favorite recordings—as the most talented artist he ever worked with, and Chrissie Hynde, Faith Hill, Ray LaMontagne, Carrie Underwood, Kurt Vile, Bahamas, and many others are also on his session resume.) Roe has come a long way from his makeshift Silvertone bass back in Ewa Beach, but that same do-it-yourself, fake-it-’til-you-make-it ethic has guided his career to soaring highs.“It always felt totally lucky and serendipitous to end up in those positions,” he says. “There’s always been people around that could have played those gigs better than me when I was doing them. But somehow, I ended up there. I just did the best I could.”

Marty Party 1995 - Johnny Cash & The Tennessee Three

Dave Roe’s experience of playing with Johnny Cash in the ’90s was just one of many remarkable successes in his long and fulfilling career.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.