There are rules, and then there are exceptions to those rules. In the musical universe, Bill Laswell has cultivated an extraordinary body of work that pretty much breaks the mold.

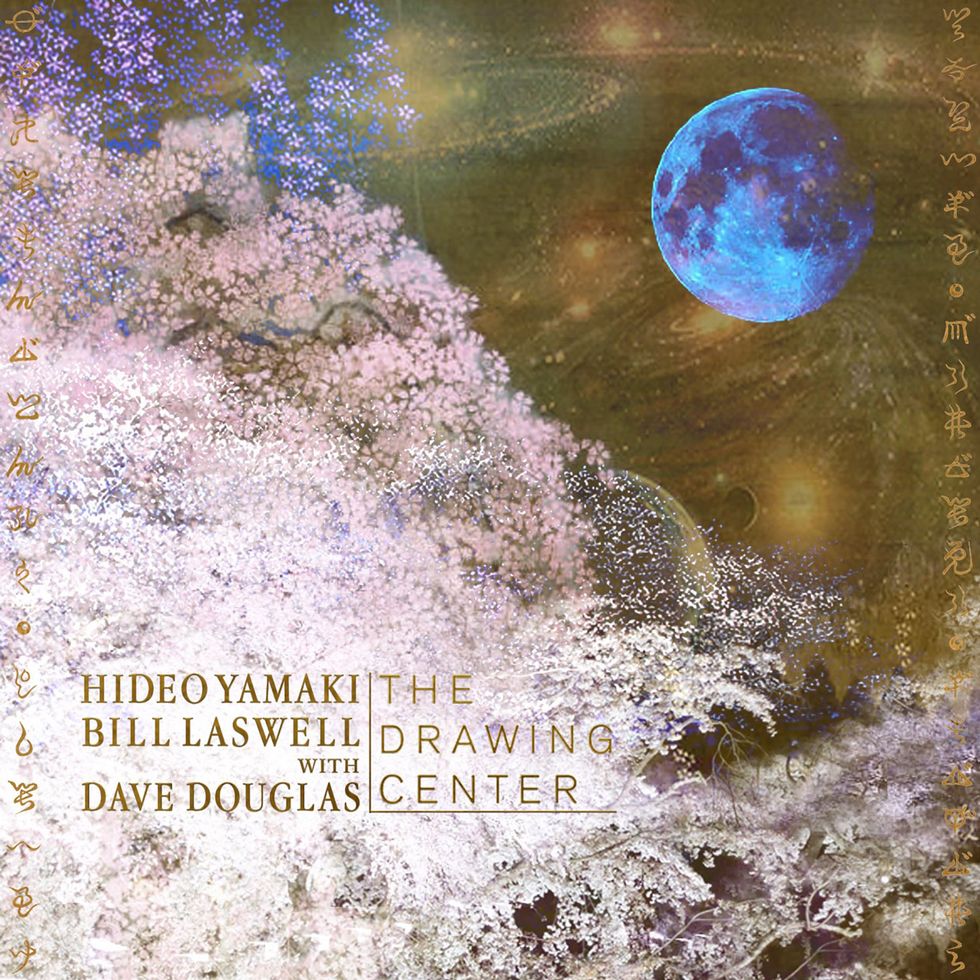

Whether producing seminal albums like Public Image Ltd’s Album and Mötorhead’s Orgasmatron (both from 1986) or playing bass in bands like the intensely abrasive trio Painkiller, he’s spent most of his career defying convention. For his recent release on his M.O.D. Technologies imprint, The Drawing Center, he teams up with trumpeter Dave Douglas and drummer Hideo Yamaki and delves deeply into a boundless sonic experiment titled “The Science of Imaginary Solutions.” The 45-minute, single-track instrumental was recorded live at New York City venue the Drawing Center in August 2016 and affirms Laswell’s relentless pursuit of momentary creative expression. Not only is The Drawing Center a live record, it’s an improvisatory one. Laswell and his mates didn’t know what they were going to play when they showed up at the gig. They simply dove into the moment, trusted their instincts, and delivered an absolutely blistering set of music that defies categorization.

“The Science of Imaginary Solutions” neither adheres to the popular music format of verse/bridge/chorus/solo nor the jazz tradition of interpreting tunes with a head, motif, and solo. It’s a bold project that combines aspects of world, electronic, dub, jazz, and non-Western traditions. Laswell, Douglas, and Yamaki tap into a vast well of experience that ultimately relies on artful, subtle repetition to undergird the opus. “Repetition is crucial,” Laswell attests. “If you can’t sustain that or sustain interest in it, you’re really just bothering people with sound.”

The Drawing Center reinforces the notion that music is most effective as an in-the-present endeavor. A dialogue emerges on “The Science of Imaginary Solutions,” which evolves intuitively as the trio converse, argue, and debate using a musical language that sounds as elemental and timeless as the universe itself. Laswell seems to be at his best in these situations. His percolating, heavily effected bass lines engage with and react to the overt virtuosity of Douglas and Yamaki. His own virtuosity isn’t as obvious. It sneaks up on you via a vocabulary that is rhythmically astute, harmonically rich, and tonally deep.

Growing up in Albion, Michigan, Laswell started playing bass because he made a conscious decision to “not do all the other stupid things” that were available. “Music was a bit safer and you might even get lucky, so I decided to go that way,” he recalls.

Since almost everyone he knew played either guitar or drums, he chose bass, but literally started with a guitar and took two strings off. “There weren’t a lot of bass players and I realized that that’s the force, the pulse, of the music,” he explains. “And if you develop a sound and a way to communicate with drummers, then you really can make a very significant statement.”

Laswell has gone on to make many significant statements as both a producer and a bassist. His helming of works by Herbie Hancock, Laurie Anderson, Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare, Sonny Sharrock, Mick Jagger, and many, many others attests to his diversity and acumen. And his resume as a bass player explodes with unbound expressions of his 4-string artistry. It includes his 1983 debut Baselines, his 1987 collaboration with bass saxophonist Peter Brötzmann called Low Life, 1997’s South Delta Space Age in partnership with guitarist James “Blood” Ulmer under the name Third Rail, any of the uproarious free-improv Last Exit albums, and 2000’s Tala Matrix by Tabla Beat Science with tabla master Zakir Hussain.

Laswell says it’s easier to make a statement with a bass than a guitar: “With guitar, you must constantly redefine yourself and you’re competing with so many people, so I stuck with bass.” Completely self-taught, he gleaned the fundamentals from recordings by R&B players he says were doing “pretty simple music,” like Chuck Rainey and Donald “Duck” Dunn.

Despite his taste for daring music, Laswell is a disciple of the Stax and Muscle Shoals sounds and prefers that vibe to the more fluid Motown bass approach. His reasoning illuminates the basic nature of the axis on which most of his own music rotates, no matter how dense or seemingly complex. “Stax and Muscle Shoals were simple,” he states emphatically. “And it was more feel-oriented. I could relate that to and apply it to dub and reggae. Motown was a lot of jazz musicians who all had their own thing, but they weren’t good enough to be jazz musicians, so they were in Motown. They were great at what they did, but to me it was a little complicated and jazz-oriented compared to something like Stax.”

By the time he was 15 years old, Laswell was playing in R&B bands touring from the urban north to the south and along the East Coast, traveling from Detroit, Michigan, to the Florida Keys. He was in the “Chitlin’ Circuit”—an informal network of venues that catered to African-American music lovers, which were often owned and booked by black promoters, and were safe harbors for black musicians since the days of Jim Crow.

Laswell says playing those venues “made an impression and gave me a foundation. There’s subtlety. There’s simplicity. There’s no other agenda. You’re just right there with the notes that you’re playing. These days, for young musicians coming up that’s probably impossible because everything is so complicated in every way—technology, career.”

Laswell believes the pressure to wear multiple hats has become detrimental to the growth of young players. “First, you have people setting standards that are pretty low and, again, you’re competing with technology, technique, image, presence. It goes on and on. But very little of that is as simple as someone sitting down and saying, “I think I’m going to play this…”

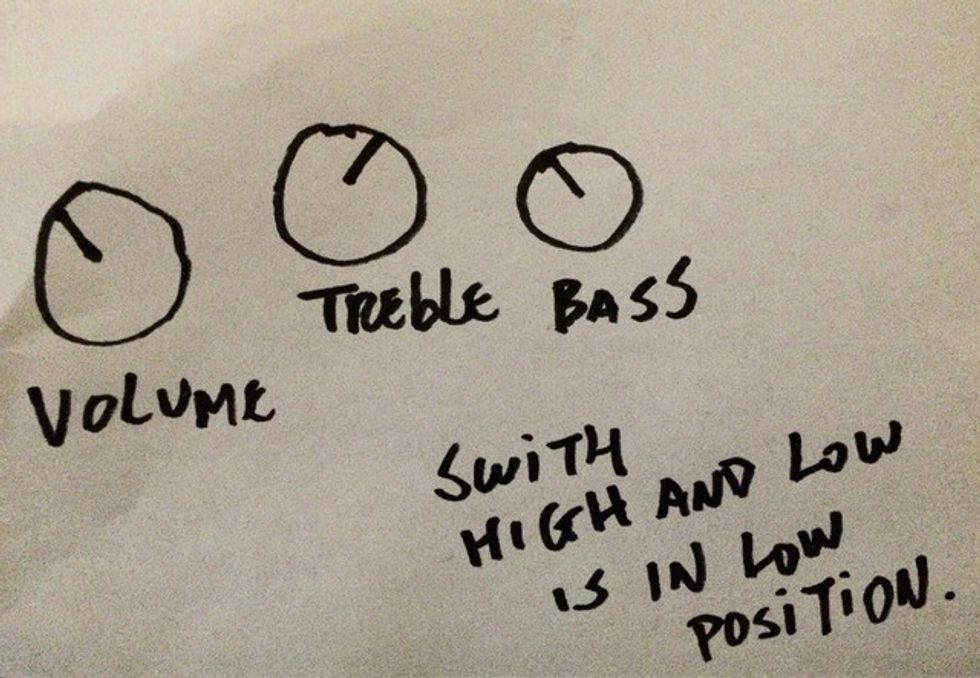

Despite his lofty conceptual achievements, Laswell is a meat-and-potatoes player at heart. When asked to explain how he runs his beefy Ampeg amp heads, he offered this drawing.

Playing funk, R&B, and other groove-based music on the Chitlin’ Circuit formed Laswell’s understanding of the relationship between a bassist and a drummer—something he feels is missing in a lot of contemporary music he hears. “When it works, it’s one thing,” he relates. “It’s not two people. It really serves as one functioning time machine. You’ll hear it when it works and it’s not always because they’re playing together, necessarily. It’s just the way they interpret space.”

He cites reggae rhythm dream team Sly and Robbie and Stax’s classic bass and drums chair holders, Duck Dunn and Al Jackson Jr., as good examples of rhythm sections that function as one entity. “Rock bands—not so much,” he says. “I don’t ever hear the bass and drum relationship unless you have a bass player who’s totally listening, like the guy in the Who [John Entwistle]. Keith Moon was all over the place, but the bass player managed to listen to it and it created this feeling that they were together. Led Zeppelin was the same. I thought the bass and drums were interesting, but I wasn’t always into the scratchy guitar and high singing. I really thought the bass and drums anchored that band.”

Bill Laswell’s The Drawing Center is a 45-minute, single-track, improv instrumental album recorded live at New York City venue the Drawing Center in August 2016.

Laswell has designed his M.O.D. Technologies umbrella for the musical variety and flexibility that inspires him. One day he might be creating dub music, electronic/ambient sounds the next, and maybe in some kind of African-influenced situation after that—each time with a different cast of musicians.

Though evolving as a musician is important to Laswell, he explains it’s not necessarily the key to everything. “If what you do maintains some value, some point of interest for listeners or fans, then there’s nothing wrong with that kind of fixed format,” he says. “ZZ Top has been around forever and to me they still translate. U2 has been around a long time and they’ve been consistent with their work. There are very few good examples. In most situations people are stuck together out of a sort of desperation or fear or necessity. I’ve steered away from that intuitively.”

Although musical diversity is what keeps Laswell motivated and moving, it’s clear from his R&B background and his production aesthetic that he’s as interested in music that’s raw and immediate as he is in genre-crossing or expressionistic sounds. In addition to coproducing Mick Jagger’s solo debut, 1983’s She’s the Boss, and the aforementioned Mötorhead and Public Image Ltd albums, he’s also cut discs with Iggy Pop and White Zombie, and has a fondness for punk rock.

Bill Laswell's Gear

Bass• 1977 Fender Precision with a modified fretless neck and Leo Quan Badass bridge

Amps

• Ampeg SVT-CL heads

• Ampeg SVT-VR heads

• Ampeg SVT-810E cabs

• Ampeg SVT-215E cabs

Effects

• Aguilar DB 900 Tube Direct Box

• Boss DD-3 Digital Delay

• Boss DD-7 Digital Delay

• DigiTech Bass Synth Wah

• DigiTech Whammy II

• DigiTech EX-7 Expression Factory

• DOD 545 Wah Filter

• Dunlop 105Q Cry Baby Bass Wah

• EBS UniChorus analog bass chorus

• Electro-Harmonix Bass Big Muff Pi

• Ernie Ball 6166 Mono Volume Pedal for passive electronics

• Moogerfooger MF-102 Ring Modulator

• Pigtronix EP2 Envelope Phaser

Strings

• D’Addario ENR72 Half Rounds, medium (.050–.070–.085–.105)

“There is an energy and attitude,” he says, referring to the genre. “A statement is being made, and if you mix that into hardcore and prog, you have something aggressive that will stand up.”

Laswell blended those elements as a member of John Zorn’s Bladerunner, featuring the band’s namesake saxophonist as well as drummer Dave Lombardo from Slayer. In Laswell’s universe, such endeavors are not simply vanity projects meant to bring together his buddies, but a chance to have a cathartic experience that wipes the slate clean for whatever might come next, artistically speaking.

“Every once in a while, it’s a way to blow out all of the dust,” he says. “It’s something more visceral, more aggressive, louder and more dangerous. It wakes us up to the possibilities of shock and impact and how sound can be a real force. Every few years something like that comes around. That’s been inspiring and good—a quick cleansing feeling that blows out all of the things that get stuck.”

As the conversation circles back to The Drawing Center, Laswell divulges that, even though nothing was discussed beforehand, familiarity with each musician’s skill set contributes to meaningful improvisations. “It’s totally improvised, but I was conscious of the other musicians and I know that someone like Dave Douglas, even though he’s a virtuoso player, has an interest in music that’s repetitive—he’s into beats and rhythms. So that’s a given,” Laswell says. “You know you’re not taking someone out into an area they don’t want to play in. You have to take that into consideration.”

He’s also worked with Yamaki for a long time, on improv recordings like Untaken Path and The Stone, as well as straight gigs where they just play “one thing over and over,” so they brought their established relationship to The Drawing Center. “When you do those trios, everybody should bring what they do. It moves in and out because it’s improv, and it could’ve gone a completely different way, but that’s what happened that night.”

There wasn’t even a discussion about tonal center on The Drawing Center. Similarly, Laswell’s best-known improv outfit, Last Exit, which teamed him with Brötzmann, drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson, and free-jazz guitar icon Sonny Sharrock, never played a note together until they hit the stage for their first gig. That may seem perplexing in that sometimes it’s hard for horn players and string players to find common ground in regard to a comfortable key signature for both parties. “I use all of the open strings, to get the harmonics, so I’m pretty much in this pitch center most of the time, unless it’s atonal,” Laswell explains. “But sometimes it can be a challenge for horn players who are dealing with E-flats and B-flats. So far, most of the people I’ve worked with are evolved, so they know the reason I’m using the open strings.”

Laswell plays a modified 1977 Fender Precision bass about 90 percent of the time. “It travels well and it’s versatile,” he explains. “It can be very warm and do clearer things, too.” He’s been using Ampeg amps since he was 16. “Same setting, same head [see Laswell’s drawing above]. As many of them as possible if it’s a big stage.” As for right-hand technique, Laswell plays mostly with his fingers. “I don’t have any technique with a pick, but I do use it for certain things,” he admits. As a matter of fact, he uses a pick so infrequently, he never knows what he’s using. “I just ask somebody for one if I want to use one.”

Effects make up a large portion of Laswell’s tonal palette. He says the true test for any effect is to use it live. He reasons that the studio is too much of a controlled environment to fully understand how an effect will respond.

Although many pedals circulate in and out of his pedalboard, he relies on a few staples to help achieve his notoriously deep bottom-end bass tone: a DOD 545 Wah Filter with a setting for only bottom end, a Pigtronix Envelope Phaser he uses for back-up bottom end, and a DigiTech Whammy II with detuned settings.

Laswell’s recordings are known for having deeply present bass sounds, but his approach to capturing those tones is as simple as his ideas about feel and repetition. “There are so many variables step by step,” he offers. “It really starts with the bass and how you play it. And then it depends on what strings work well with that bass and how it’s set up, how the action is, etc. A lot of people never even get there. They just start playing without these fundamentals, but if you should get through that, the next thing would be ‘what’s the compatible amplification for that approach?’ And when you get all that done, it’s all about how you interact with the rhythm and the drummer.”

In addition to The Drawing Center, Laswell and M.O.D. Technologies have also released Jajouka with Material—a live pairing of Laswell’s longstanding collective Material with the Master Musicians of Joujouka, who are based in the Sufi tradition—and Inaugural Sound Clash, which captures a quintet that includes Laswell and Yamaki.

The bassist says M.O.D. Technologies and the projects under its umbrella were inspired by a shift in the music industry. “There is less backing in financial terms,” he says. “We did have some help, but there is no connection to any such thing as a major label or any international facility that can make it available in many territories. It’s downsizing, but it’s not my decision to downsize. It’s a collapse. Everything is twice as hard as it was, but that doesn’t mean you can’t do it."

For musicians wanting to follow his non-conformist model, Laswell shares this advice: “If someone is trying to do music and start a label and start whatever the word career is supposed to be these days, I think you either must get very lucky very quickly or you work as independently as possible, but you will still need money. And that money is not necessarily going to come from somebody who loves your work—somebody who’s going to give you a publishing advance. That model is already 20 years old. You need to find funds, and that can come from relatives, friends, or it can come from other musicians. Money is with the people who have money, and if you want money, you go to those people.”

YouTube It

Laswell’s outfit Last Exit, including guitarist Sonny Sharrock, reed player Peter Brötzmann, and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson, comes roaring into a pair of intense improvisations from a mid-’80s performance in Frankfurt, Germany. There’s a rare chance to see Laswell play with a pick at the 90-second mark, and he duets with Brötzmann at about 6:30, leading to passages of slapped and tapped strings.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)