|

He’s scored over 10 million album sales, 14 No.1 hits, boasts a virtual army of fans that cuts across generations, and sells out wherever he performs. He has won three Grammys and multiple Country Music Association and Academy of Country Music awards. As of this writing, he has been nominated for seven more CMA trophies.

From the beginning, Brad managed to use his road band in the studio—no small accomplishment in Nashville—and he’s charted his own course every step of the way, fortunate to have management and a record label that have given him free reign to do as he pleases. Very few Nashville artists can boast his accomplishments as a singer, songwriter and prodigious instrumentalist. Unlike People, however, we’ll focus on Brad Paisley, guitarist and gearhead extraordinaire. From his home in Franklin, TN, Brad and I spoke about equipment, his influences, his equipment, tone, his wife’s tolerance of that peculiar affliction known as G.A.S. (Gear Acquisition Syndrome), his equipment … and more equipment, his trademark pink ’68 Fender Paisley Telecaster. And by the way, his last name really is Paisley.

Let’s start by talking about the Play album. Can you tell us how that came about and what you had to do to make it happen?

Not a lot. I did a Christmas album between Time Well Wasted and 5th Gear, and I had such a good time making it that I wanted to do another low-pressure record and not have to worry about hit singles. I enjoy making commercially viable records, but there’s something to be said about making an album that’s selfish in a way. I had always wanted to do an instrumental record. The records that stand the test of time to me are instrumental albums, like Ah Via Musicom by Eric Johnson. We didn’t want to do something that was self-important, and we weren’t out to save the world or win song of the year.

It sounds like there was some compromising that must have occurred with that record. I’m sure your record company wanted hit singles, didn’t they?

They didn’t expect any singles. It was really easy. They said, “Here’s your budget. It’s lower than usual, but if you can make the album for that much, go do it.” After we finished it, they were ecstatic. Joe Galante, the president of my record company, believes that artists need to grow, and I respect him for that. Of course, we had a hit with that track with Keith Urban, “Start A Band,” but it wasn’t a preconceived thing to try and have a hit. Doing an instrumental album was great for me personally. We played on The David Letterman Show around that time, and their guitarist Sid McGinnis came out and talked with me, along with Paul Shaffer, so it did a lot for me as a guitarist.

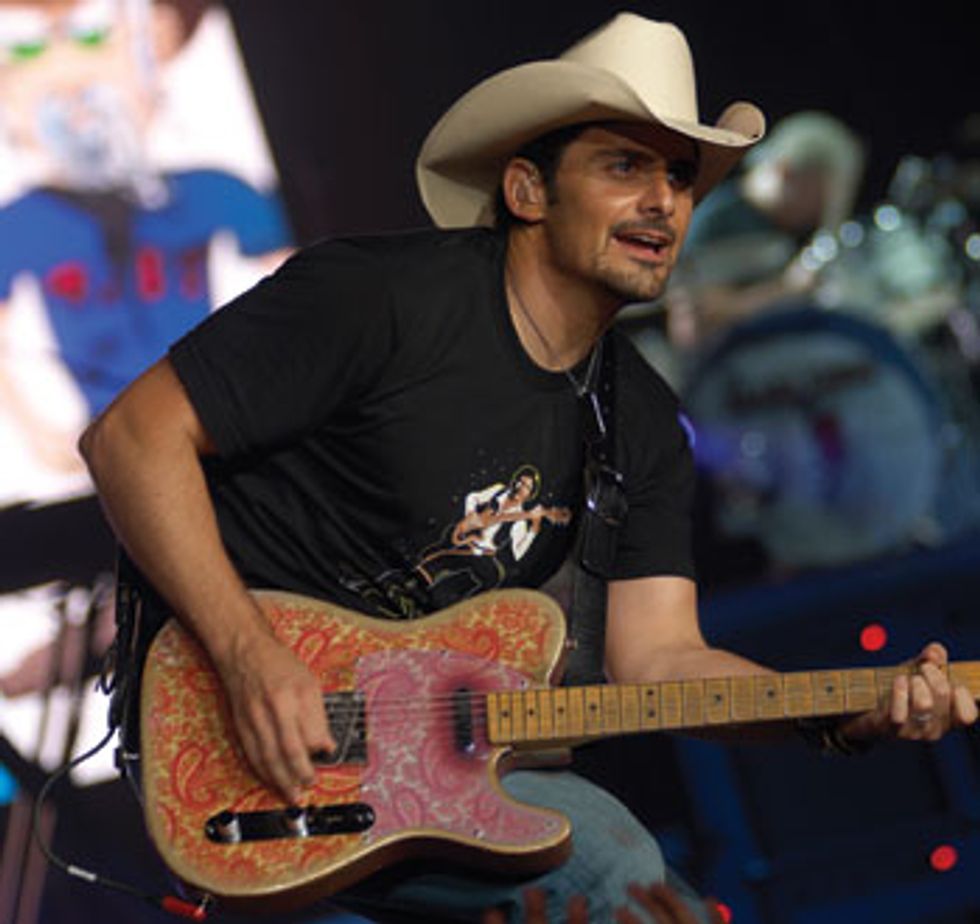

Photo by Ben Enos, 2008 |

Those were my top seven guys: James Burton, Albert Lee, Redd Volkaert, John Jorgenson, Vince Gill, Steve Wariner and Brent Mason. If you put them all in a blender, it would probably come out as me. They were all influences. I think all of us try to emulate our heroes, but we’re never as good as they are. It was a real thrill to have them all participate. James Burton is the father of all those great Telecaster licks, and it was an honor to have him as part of that track. He had requested to meet me because he’d seen me on TV. James played that Paisley Tele with Elvis and Emmylou Harris and made it a very collectible instrument. Today, those original Paisley Teles go for about $15,000.

I just saw his original Paisley Telecaster in the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland.

They have so many great guitars on display there.

Do you agree or disagree with the Nashville tradition of using studio musicians versus an artist’s road band in the studio?

I definitely disagree. I use my band and have from the beginning. My band is highly capable, and I have great drummer, but I can understand that if you go into the studio with your road drummer or any musician who isn’t familiar with the recording studio, you will have problem. There are a lot of reasons why they use studio musicians. Nashville is a very small, tight-knit community. It’s also because those studio cats are just such great players.

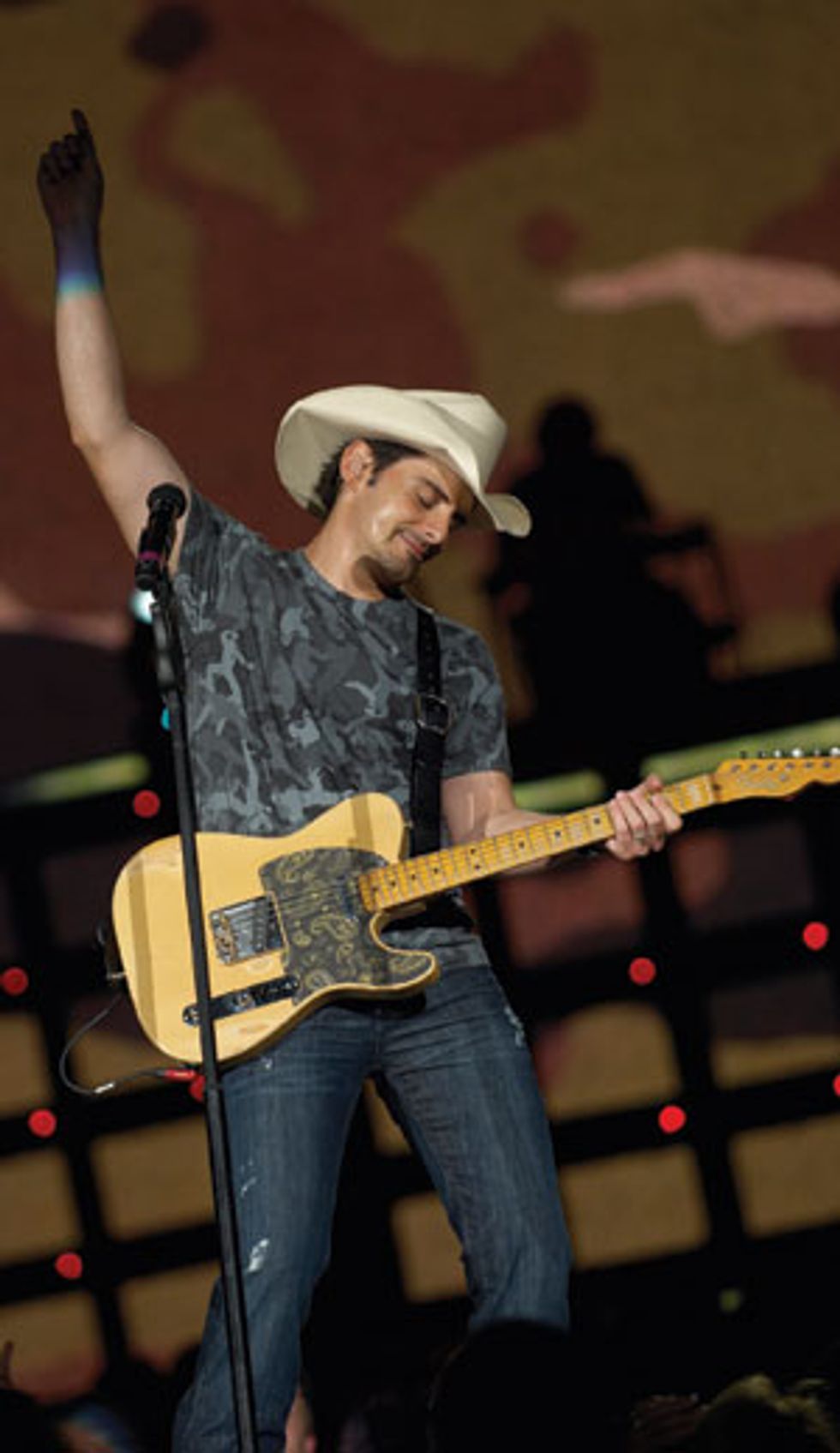

Photo by Ben Enos, 2008 |

How did you get started playing guitar?

It was my grandfather. He used to sit in a chair on the front porch and play guitar. He worked for the railroad and didn’t go to work until 1 pm, so he sat and played one song after another. He was in love with the guitar, and used to give me advice and tell me that playing guitar would be a life-changing thingfor me. He taught me how to play initially, and then I took lessons.

One of the reasons we wanted to feature you in Premier Guitar is because you’re a self-admitted “Gear Hound.” What were your first instruments?

I had a Sears Silvertone my grandfather gave me, then a Sekova ES-335 copy. I didn’t have a high-quality instrument until I got a Tokai electric. You know how it is—you want a guitar that’s different, one your friend doesn’t have, so you buy it. Then your friend gets something really cool and you have to have one like that, so you buy one. Next thing you know, you have a house full of guitars.

It’s Teles in the studio and onstage, of course, but do you use any other acoustics and electrics either live or in the studio?

I’m identified with that Tele sound, but I use lots of stuff. I use an old Gretsch. I have a Gibson ES-335 that I use in the studio. I have a Music Man Albert Lee model that’s like a Strat. I love Gibson hollowbody guitars: ES-335s, Byrdlands, and those later Chet Atkins models that Gibson made. It makes me look like I have some class! For acoustics, I like older Gibsons and Martins, as well some newer handmade guitars.

I have a ‘70s Les Paul, but I have never felt comfortable with it for some reason. It’s never felt right to me. It isn’t nimble, if that’s the right word.

It’s been said you were responsible for bringing the Telecaster back to country music after it seemed to disappear. Do you think that’s true?

Is it back? I don’t think it’s really back. I don’t hear a lot of Tele-heavy stuff going on. I was a big fan of Buck Owens and Don Rich, and most of my heroes play Teles, so it was natural for me. I was just hoping they didn’t laugh me out of town! Country music runs such a wide gamut these days, from stuff like mine to harder-edged music, so you have guys using different guitars.

Keith Urban plays a Les Paul Junior; that’s never been considered a country guitar.

That’s right, but it works for him. I can’t take credit for bringing the Tele back.

I saw the photo of you with an old non-reverse Firebird in the booklet of Play. Was that the guitar you borrowed for that track with Steve Wariner, “More Than Just This Song?”

Yes, that Firebird belonged to my guitar teacher, Hank Goddard, from Wheeling, WV. He was a fantastic jazz player and a great teacher. Had he gone to Nashville at the right time, I’m sure he would have done very well, made a lot of money, and would have provided a better life for himself and his family. But he wouldn’t leave West Virginia. He had this idea that Nashville musicians were always on tour, but session musicians do their playing like a normal job and go home and have dinner with their families.

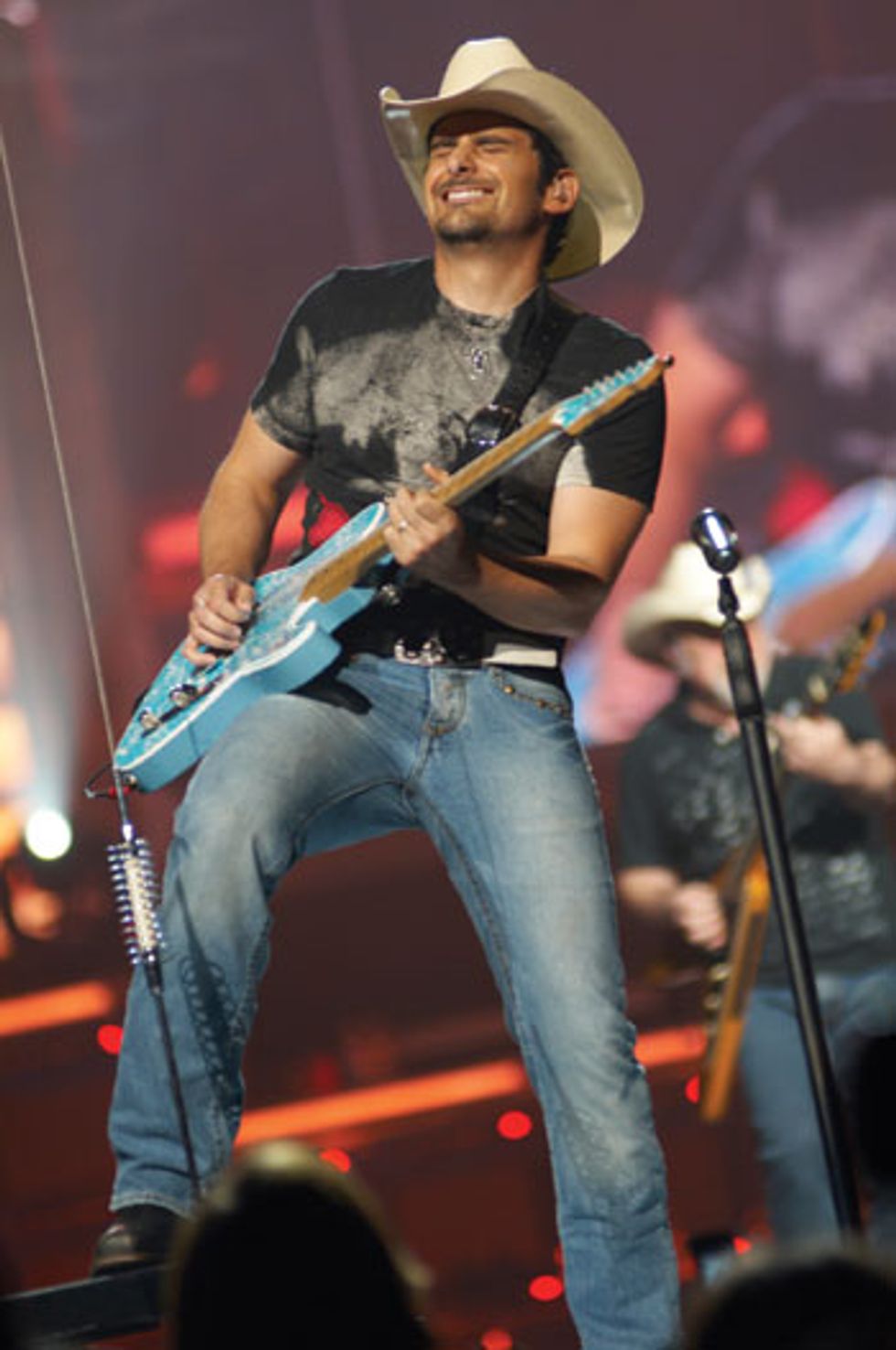

Photo by Ben Enos, 2008 |

I use my ’68 Paisley Telecaster, and the rest of them are custom made for me by Bill Crook, except for my “mutt” Tele that has a ’52 refinished body with a ’56 neck. The ones Bill has made for me include a black paisley Tele, a blue paisley Esquire, and a new blue sparkle paisley Esquire. I also use a Gibson Country Gentleman and a Music Man Albert Lee.

What is it about Bill’s guitars you like?

Bill makes guitars the way you want them. You might wait eight months for one, but if you’re willing to spend two to three grand for one of his guitars, you’ll get one exactly the way you want it. I’ve known Bill since I was eight years old. He worked in a music store in West Virginia. That was a nice write-up you did in your magazine on Bill a while ago.

Thank you. You’ve mentioned that you prefer using a G-Bender versus a B-Bender. Why is that?

I just like the sound better. It’s less piercing and trebly—more subtle and again, different. I wanted to sound like myself and not be compared to Steve Wariner or Clarence White. People think I thought up the G-Bender, but it was Joe Glaser who came up with the idea of a double bender years ago. My G-Bender guitar pretty much stays at home now.

Was that the guitar you used on “Waitin’ On A Woman?”

Yes, that was the one.

| Click here to read Bill Crook, Dr. Z and Robert Keeley's take on Brad Paisley and his gear. |

I always loved the sound of AC30s, but after my first major tour and a few good falls down the steps, I decided I should find something with that British sound that could withstand the road. I tried a Dr. Z with 10” speakers, and it sounded like my old AC30. Mike Zaite has a philosophy: make world-class amps and make them affordable. I think they’re just about the least expensive of all the boutique amps out there. I’ve used Mike’s amps on TV and on tour, and he sends me amps to try at home, things he’s working on. It’s been fun to watch the company grow.

Live, I use the Dr. Z Remedy and a special Z-Wreck that was made for me. Mike, Ken Fischer and I collaborated on that. I actually use all kinds of amps in the studio, including old Marshalls with 6V6s. I always am on the lookout for something that’s different. I’m always looking for that angle. I like to switch amps onstage for different things.

Did you ever think it might be easier to simplify your live rig, and if so, how would you do that?

It’s pretty involved onstage just because it can be. I can get away with it. Sure, I could do a show with one amp and two pedals, but it wouldn’t be too good for the people in the back rows.

Talk to us about your stompboxes.

I use Keeley pedals and Keeley-modded pedals, as well as a few other things, like the Fulltone Echodrive and a modded 808 Tube Screamer. I don’t use compression on my Tele, but I do use a lot of delay. Robert Keeley is just great at tweaking pedals and building new ones based on older designs. He’ll hear something, take it into his shop and change the character completely. It goes back to what we said about not sounding like anybody else, about having a different guitar than your friend. It’s the same way with pedals. You always want to sound different. Robert takes things to sonic places where no one has gone before. He’s very passionate about his work, and I like passionate people.

I hear a lot of jazzy chord changes and riffs going on in your music. Is that true?

| BRAD'S LIVE GEARBOX Guitars: 1968 Paisley Fender Telecaster Three Bill Crook Tele or Esquire replicas in black paisley, blue paisley and blue sparkle paisley ’52/’56 “Mutt” modded Fender Telecaster Gibson Chet Atkins Country Gentleman Music Man Albert Lee hardtail. Amps: Dr. Z Remedy and Z-Wreck Vox AC30 handwired by Tony Bruno Tony Bruno Underground 30 Effects: Four delays: Way Huge Aquapuss, Modded Boss DD-2 and DD-3, Maxon AD-999 Fulltone Echodrive Modded Ibanez 808 Tube Screamer Modded Boss Blues Driver Hermida Audio Technology Zendrive Keeley Compressor and Katana pedals Line 6 M-13 with 12 presets for tremolo, vibrato and other effects Modded Dunlop wah-wah. Accessories: Ernie Ball .010-.046. Strings Ernie Ball medium or heavy picks Custom cables made by Guitar-Cable.com Shure wireless system Custom straps made by Matt Ali of West Virginia. |

The catch phrase at Premier Guitar is “The relentless pursuit of tone.” How would you define great tone, and do you agree it’s a very subjective thing?

It is very subjective. But to me, when someone says, “I love that,” then that’s great tone. I’m very picky about little stuff. If I’m playing a clean sound with my Tele, I can tell if a cable has been changed. You really can hear those things. I’d say that great tone is when raw emotion is allowed to pass unencumbered from your hands to the speakers so people can relate to it. I love tone when it’s allowed to bloom.

Does your wife understand your obsession with gear?

Yes, she does, fortunately. It’s not a big issue because these are the tools of my trade and I can afford what I want. This is how I make my living. If you’re in the construction business you need to buy bulldozers and tools. I’m a musician, so I buy musical equipment. [Authors Note: try that explanation on your wife next time you plan to drop a few grand on a custom shop axe!]

My wife is so jealous. The other night, Vince Gill and I went to the Belcourt Theatre in Nashville to see Robben Ford, and we went onstage and sat in. My wife was in the audience. Later on, she said to me, “You guys had the most amazing conversation up there and you never said a word.”

She and I have always had an agreement that if either one of us spends more than $5000 on anything, we discuss it first … you can buy a lot of cool stuff for less than five thousand bucks!

The author would like to thank Bill Crook, Mike “Dr. Z” Zaite, Robert Keeley and Brad’s tech, Chad Weaver, for their help in preparing this article.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)