In 2006, Chan Marshall was visiting a shop in Memphis when she happened upon an instrument—not necessarily one that most readers of this magazine would find covetable—that spoke to her. It was an abused, no-name nylon-string that cost only $40. Marshall, who performs under the stage name Cat Power (borrowed from a trucker’s hat decorated with the phrase Cat Diesel Power), has since relied on the instrument as her songwriting muse, and she used its subdued voice to excellent effect on her latest album, Wanderer, her first in six years.

At 46, Marshall, whose first name is pronounced Shawn, has long been an indie-rock icon. After a childhood spent in Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee, where she absorbed the region’s Baptist, blues, and country sounds, she moved to New York City in 1992 and was exposed to an entirely different scene of free jazz and improvisation. Her earliest shows in the city were semi-improvised, but beginning with her first full-length album, 1995’s Dear Sir—which she recorded with Tim Foljahn (Two Dollar Guitar) and Steve Shelley (Sonic Youth)—she focused on her songcraft.

On the strength of her earliest efforts, Marshall was signed to Matador Records, a premier indie-rock label. Over the course of seven albums for Matador—from 1996’s What Would the Community Think to 2012’s Sun—she laid the groundwork for contemporary independent singers like Phoebe Bridgers and Angel Olsen.

Marshall’s guitar work—on the acoustic or her customary Danelectro or Silvertone—has always been a study in understatement. On the electric, she plays chiming, reverb-drenched parts, with rolling arpeggios and the occasional off-kilter harmony that perfectly complement her soulful, whiskey-toned vocals.

She was once known for sometimes-erratic performances, owing to anxieties and struggles with substance abuse, but in recent years she has made some transformations. Marshall recently cut ties with Matador, due to mutual creative differences. In interviews, Marshall’s explained that when she presented her latest album to the label, an executive played her an Adele recording to demonstrate how he thought it should sound. That obviously did not go over well.

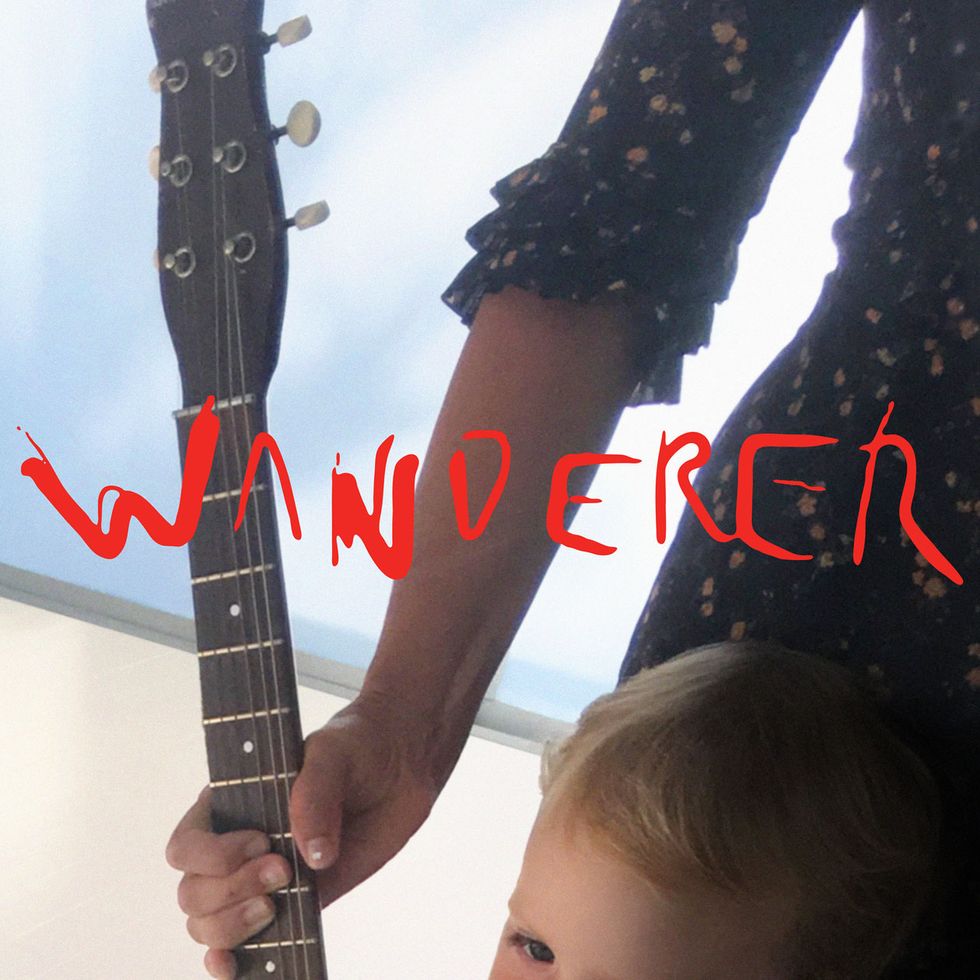

At the same time, Marshall has stepped into the role of single mother. Her toddler son appears on the cover of Wanderer, next to the neck of her Danelectro. Motherhood has put her in a protective and nurturing place, which is apparent in the album’s generally quiet and cozy vibe, with guitar- and piano-based songs that are produced much more sparsely than those on Sun, with its shimmering electronic layers.

I spoke with Marshall recently via telephone, and, with a trace of a Southern drawl, she talked candidly about how motherhood informed Wanderer. She also discussed her working processes, her no-name acoustic, her vintage Fender amps—and the importance of reverb in her life.

Your latest album is much more stripped-down than your previous one, and the guitars, both electric and acoustic, play a starring role. What did you use in recording the album?

The acoustic is a nylon-string $40 guitar that I got in Memphis a while back. I still have the price tag on it. I really don’t know what kind of guitar it is. The brand is something I can’t see, where it would have the beautiful colors—the very tiny colors around where the strings cross that big circular hole—sorry, what’s it called, the rosette?

Yes.

Yeah. The rosette is all cracked off. It really is a piece of shit, but the sound is incredible. I keep the guitar on the back of my closet door in my New York apartment.

Is that no-name guitar the one that provides the harmonic backbone on Wanderer’s “Black” and “Me Voy”?

Yes, that’s the one. I love it.

What electric guitars did you play on the album?

The electric guitar on the record is a ’59 or ’61 Danelectro—you know the one that Jimmy Page played? I don’t really know anything about guitars, but I have a few of those. The one I used for the record is a copper one that I got on eBay. It’s really old and somewhat delicate, and the tone is so beautiful. That’s the only one I think I used on the album, but I honestly can’t remember for sure.

TIBIT: Motherhood was a catalyst for Wanderer, Cat Power’s first new album in six years. For the recording process, she rented a house in Miami with her toddler son in tow and brought in all of her own gear to create a personal studio.

You have a lovely tone on the electric guitar. What are you using for amps?

Thanks, I appreciate that. There was a 1964 Fender Princeton, a blackface. That was my first amp, and I’ve had it all these years. It doesn’t have reverb on it, so I bought another one that did. And I also use a Fender Twin. But the truth is, I don’t care really care which one I use. I just like to plug in and turn it on.

“In Your Face” and “Wanderer/Exit” both kick off with electric parts drenched in warm reverb. Is it from one of your Fenders?

It’s definitely from the amplifier—probably the Princeton Reverb, but it also could be from the room, because I put different mics in different places, and I like a room mic across the fuckin’ room. It just gives you a nice sense of depth. But I honestly cannot live without that great amp reverb. I’ve tried and have survived, but it’s not a happy life without reverb [laughs].

That’s funny. “In Your Face” has an ever-so-slightly unusual chord progression….

I don’t know chords. I’m sorry. Are you mad at me?

Not in the slightest. On the album, in general your guitar has a warm and distinctive attack. Are you playing fingerstyle or using a pick?

I don’t usually use a pick. I use the fat on my thumb and the side of my forefingers to pick and strum. If I have to, though, I use a Dunlop grey medium—the dark grey one or the light grey, whichever I can find.

Marshall performs with her Silvertone 1448, which she employs for chiming, reverb-drenched parts, with rolling arpeggios and the occasional off-kilter harmony that complements her soulful, whiskey-toned vocals. Photo by Jordi Vidal

Talk about your writing process. How does a song come into being for you?

It really depends. Generally, it starts on a guitar, because they’re always around and they’re just so easy to pick up, whether I’m at home or at a friend’s house. But if there’s a piano around, whether it’s an upright or an electric, then a song might start on the piano.

Whatever instrument it starts on, the way I work best is that I have to be alone. It’s true that there are a couple of my songs that were written with people around. “I Don’t Blame You” [from 2003’s You Are Free] was written with an engineer sitting right in the next room, which was kind of a lot of pressure. In any case, it usually just starts with … I’m not trying to write a song, number one. Usually I just want to play an instrument.

There’s a reason why writers want to grab a pen and a paper. They want to jot something down when the inspiration hits. Or a photographer will lug his camera around all day, or whatever. I guess there’s a reason that musicians play music. There’s something that makes me want to grab the guitar. It’s never out of a habit, or a scheduling thing: “Oh, now it’s time for me to play my guitar today!” It’s just like an intense craving. There’s a hunger, there’s a conscious screaming or tick-tock or something that I’ve been unconsciously conditioned to do.

It just works for me.”

Anyway, I’ll just pick up the guitar, and whatever I start playing, whether it’s some chords or a riff or a little melody…. If I play that idea for long enough, and I’m not really thinking, just relaxing—I guess that’s the key—it just arrives. If something comes out of my mouth, you know, and it’s words, and it has a melody, I do it again. If I do it again, then I do it again. Three times in a row, then it’s a song.

If I run to the kitchen and I get some batteries, and I can scramble in the closet to find my tape recorder. If I can find a cassette, and I record it, then it’s really a song, because it’s been recorded. If I play it maybe five more times, maybe 10 times, it’s a real song. Then the next day, if I remember it … you might hear it on the next record. But if I don’t remember it, you’ll never hear it. It’s lost to the world. So that’s that.

You mentioned working in solitude. Why do you usually prefer that?

I think that I’ve always been a pretty solitary person, just because of the way I was raised—traveling around all the time, different households, different influences, different states. So I was always the new kid at school or in town. My big sister, she didn’t want anything to do with me. You know how that goes. So I just worked in solitude in general. I’ve always been fun loving, but just pretty solitary. It just works for me.

Guitars

Danelectro U1

Silvertone 1448

Nylon string acoustic

Amps

1964 Fender Princeton

Late-1960s Fender Princeton Reverb

1970s Fender Twin Reverb

Effects

None

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010–.046)

Dunlop 44P.88 Nylon Standard (occasionally)

But what was your question? Oh, yeah, working alone is just really the only way I’ve ever done it. I like being alone. I like painting alone. I like to write with the typewriter alone. I’m not self-conscious alone. I don’t have to think about anybody else’s thoughts or concerns if I’m alone. I think that, in terms of creativity, it’s important to be in contact with yourself, and with other people around that can often be hard to do.

On the other hand, if I were in the Rolling Stones in the ’60s, I’d have no problem hanging out all day, making some shit up with the band, going through bottles of wine, and jet skiing all day long [laughs]. Just kidding.

On a different note, that’s your young son on the cover of Wanderer. How—if at all—has motherhood changed you as a musician?

My son is now 3 1/2. Being a new mom—I started recording again [after a years-long hiatus] when he was just 3 months old—and recording at home definitely shaped the music. I rented a house in Miami just to begin the process. I put my studio in there. I put all my shit in the rental. So I was really connected with my child in there, and I wanted the universal space, and personal space, to be a part of the sound. I wanted to feel like time was ... I don’t even know what transfixed means, if that’s a word, but I wanted to hear time and feel a complete sense of peace.

When I had my son, I felt so safe. It felt like something from the universe. I can’t describe it. I finally understood my position on Earth. That I was needed—that I meant something, really meant something to the Earth and to this life. So I had an infinite amount of purpose and strength—strength that kicked the shit out of me and grounded me and gave me a sense of protective nature. I’ve always been very protective of my friends, but it was having my son that I think informed the record. You know, it was this sense of protection that I maybe always needed as a child, but which I never had. When you play the album, I wanted a sense of protection to exist within the sonic fucking waves.

Chan Marshall revisits her back catalog during a gig at a villa outside of Milan in 2017, displaying her fingerpicking on a solo rendition of “Say” from 1998’s Moon Pix.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)