Although he is often discussed purely within the context of surf music, Dick Dale was one of the earliest and most influential guitar heroes of the post-swing era of popular music and a central figure in transitioning ’50s rock ’n’ roll to a more raucous breed of ’60s rock.

Rarely has the phrase ”ahead of his time” been so aptly applied as in the case of Dick Dale, who died at age 81 on Saturday, March 16, while in treatment for heart and kidney failure at the Loma Linda University Medical Center in Loma Linda, California. Dale used his equipment, unique playing technique, and the power of sheer volume to create a musical experience of the sort that wouldn’t be the norm among other guitarists for another half-decade or more—in the process, earning the title “the Father of Heavy Metal,” in addition to having been crowned “the King of Surf Guitar.” In so doing, Dale also played a major role in shaping the equipment needed for this bombastic new form of cultural expression, thereby both enabling and legitimizing the pure need for power for future generations.

Dale was born Richard Monsour in Boston in 1937 to a Lebanese father and Polish mother, and the music of both cultures was central to family life throughout his youth. After dabbling in piano and ukulele at an early age, Dale was taught by a musical uncle to play the tarabaki (aka goblet drum) and oud (a Lebanese and Middle Eastern stringed instrument similar to a fretless mandolin). He would later say that the rhythmic tarabaki technique influenced all of his playing since—percussive leanings that would be further enhanced by his love of the wild, aggressive drumming of jazz star Gene Krupa. All of these influences were translated to the guitar after Dale purchased his first 6-string from a school friend for $8.

In 1954, Dale’s father, a machinist, took a job with Hughes Aircraft in California, and the family moved to the opposite coast, settling in El Segundo. Learning to surf at the age of 17, Dale became quickly and deeply immersed in the scene, but while he would soon merge that cultural phenomenon with the music he’d come to love, he first launched his performance ambitions on another genre: country music. The adventure gave him his new stage name, Dick Dale—courtesy of fellow country performer Texas Tiny, who said the new appellation sounded a lot more like a country artist than “Richard Monsour”—but the music didn’t stick. Dale was inexorably drawn to the surfer scene, and that’s where the power of his playing exploded.

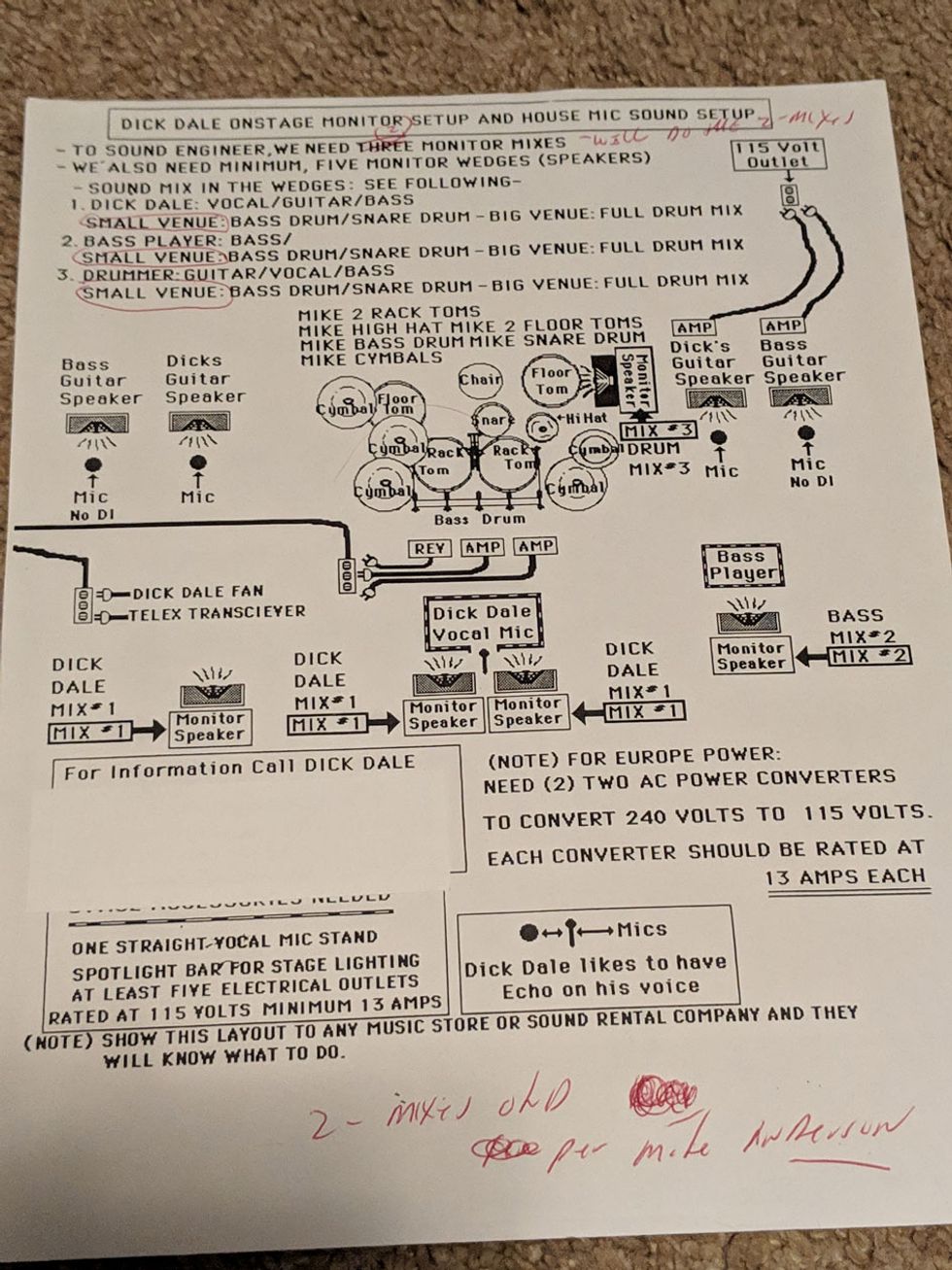

Dale knew exactly how he should sound—onstage and in the house. He had precise specifications that venue sound engineers were expected to follow, and he arrived at each show with a map to guide them. Photo by Steve Kalinsky

Surf music might be considered a genre of the early ’60s, but most critics agree that Dale gave birth to the wave in the late ’50s. Performing as Dick Dale and His Del-Tones, with Dale’s guitar front and center, the guitarist pioneered an aggressive, pounding, rapid-fire, tremolo-picked playing style that deliberately sought to replicate the wild, swirling experience of catching a monster curl. Early on, the band played at local ice cream parlors and other available venues, but as the crowds—and the volume—outgrew such locations, bigger rooms were needed.

From 1959 to early ’61, Dick Dale and His Del-Tones packed the Rendezvous Ballroom in Balboa, California, with 3,000 to 4,000 screaming, stomping surf fans nearly every weekend night of the year, afterward taking the show to the Pasadena Civic Auditorium in 1962.

Dale had released the singles “Ooh-Wee-Marie” in 1958, “Stop Teasing” in 1959, and “St. Louis Blues” in 1960—all on his own Deltone label—before consolidating the sound in his first big surf-guitar hit, 1961’s “Let’s Go Trippin’.” A cut from his first full album, 1962’s Surfer’s Choice, the single was released a full two months ahead of the Beach Boys’ first hit, “Surfin’.”

Dale’s defining recording and most long-lived hit would come that same year, with the release of “Miserlou.” Propelled by Dale’s furious tremolo picking, the single delved into his early Middle Eastern influences to translate this traditional Eastern Mediterranean folk song into a pure, adrenaline-fueled expression of the surf experience. That same year, Dale and His Del-Tones further consolidated their presence with an appearance in the movie Beach Party, starring Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello.

By this time, Dale had already caught the attention of another Southern California phenomenon, Leo Fender. The left-handed Dale had been playing a right-handed guitar that remained correctly strung, meaning the bass strings were on the lower side of the neck, and this is how he attacked a right-handed Stratocaster when Leo handed over the guitar and urged him to “beat it to death” (as recalled by Dale on his website, dickdale.com). Fender would eventually make left-handed Strats for the artist, including several custom models in later years, notably seen in the chartreuse metal-flake signature model known as “the Beast” (sometimes produced as a right-handed guitar with a left-handed headstock), which he strung with an outrageously heavy set, running .016–.060.

Never shy about setting the record straight, Dale told Planet Magazine in September 1995 how badly much of the surf-guitar sound had been misconstrued: “You got books out there with all these different kinds of guitars that have nothing to do with the sound that Dick Dale created. The sound is a Stratocaster guitar. It’s the solidity of the wood—the thicker the wood, the bigger and purer the sound. It was a Strat. Not the Jaguar, not the Jazzmaster.”

Fender’s gear had an arguably greater influence elsewhere, though, in the form of Dale’s amplification. To satisfy the crowd’s lust for action and fuel the frenetic “surfer stomp” that was born at these shows, Dale generated furious levels of energy—and copious amounts of sheer volume—to translate surfing’s extreme physical experience into a representative musical performance. And in so doing, Dale started blowing up his Fender amps at an alarming rate.

Finding the early Fender Showman models of late ’59 or early ’60 ill-equipped to survive the maelstrom of these live performances, Leo and Fender engineer Freddie Tavares conscripted Dale to help develop a better and more robust 85-watt piggyback amplifier. While Dale tore through 48 amps in the R&D phase, part of the solution came in sourcing an adequate output transformer (henceforth known as the “Dick Dale OT”), but the final piece of the puzzle involved installing two big, sturdy 15" JBL speakers in a single closed-back cabinet. The Dual Showman was born.

When Dale returned to recording in 1993, for the album Tribal Thunder, he had undiminished vigor and still brandished the original Strat Leo Fender had made for him, which he named “the Beast.”

Although the heavy use of spring reverb—most prominently supplied by Fender’s Reverb Unit, but also from other sources—has arguably been tagged as the surf-guitar effect of note for nearly six decades, and features prominently on Dale’s hit “Miserlou” and others, the guitarist himself was always quick to set the record straight. “Reverb had nothing to do with the surfing sound,” Dale told Planet Magazine. “No! We created the reverb because Dick Dale did not have a natural vibrato on his voice. I wanted to sustain my notes while singing. Our first album, Surfer's Choice, sold over 88,000 albums—locally! That’s like more than 4 million today. Dick Dale was already established as King of the Surf Guitar, and that album did not have reverb on it. It wasn’t even invented!” Obviously, that last remark is untrue, but when it came to his art, Dale—who routinely referred to himself in the third person—was never short on hyperbole.

The explosion of the Beatles and the British Invasion of the mid ’60s led Columbia to drop Dale from its roster in 1965. That same year, Dale was diagnosed with rectal cancer at the age of 28. He eventually recovered, but the health scare kept him away from music for a time, and he largely considered himself retired throughout the ’70s. Among his endeavors during those years was raising exotic animals and founding and operating the Dick Dale Skyranch Airport in Twentynine Palms, California. In 1987, he and Stevie Ray Vaughan recorded a duet of “Pipeline” for the Avalon/Funicello film Back to the Beach, and in 1993 he released his first full album of entirely new material in almost three decades, Tribal Thunder. The biggest boost to the Dick Dale comeback came the following year, however, when director Quentin Tarantino used his recording of “Miserlou” from 31 years earlier as the theme tune for his cult hit Pulp Fiction. Dale was back—but big.

While fans might have been thrilled to see Dale tour right into his late 70s, and the born showman clearly enjoyed the spotlight himself, the effort wasn’t purely for the roar of the greasepaint and the smell of the crowd. In July of 2015, at the age of 78, Dale told the Pittsburgh City Paper: “I can’t stop touring because I will die. Physically and literally, I will die.” Years of diabetes and extreme renal failure had not only taken their toll, but had taxed Dale’s finances to the point where he needed the income from touring to top up those expenses that his health insurance wouldn’t cover.

Whatever his motivations, Dick Dale’s influence on the course of the electric guitar in popular music was profound, and lasting.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)