In 2008—after nearly a decade of making roots-based music go pop, and winning two Grammys along the way—the collective consciousness of Ben Harper and the Innocent Criminals had started to fade. Both personally and musically, the band was failing to evolve and grow. It was time for a change. So Harper focused more on his hard-rocking Relentless7 group along with some select solo projects.

Among those projects was a pair of albums that had been on Harper's list for a while. He paired up with an elder statesman of the blues, harmonica legend Charlie Musselwhite, for Get Up!, a fantastically authentic straight-up blues album that was as honest and well-executed as anything in either artist's catalog. Harper says that a sequel to the Grammy-winning collaboration is in the works. On the flip side, Childhood Home, a collection of tunes with his mother, Ellen, brought his sphere of influences full circle. “I don't think I would have even been ready to do it until a year or two ago," states Harper. “Of course, we all love our parents and we love our mom, but I just saw her clearly as a peer and as a person in a way that I hadn't up to that point. That album is a celebration of family."

In late 2014, Harper announced he was going to round up the Innocent Criminals for a run of shows at San Francisco's Fillmore. “I didn't want to pick up where we left off," he says. “I can't see the growth in that." But from the start it was obvious this wasn't a reunion with a goal of headlining the latest trendy festival. It became an evolution—maybe even a rebirth—of the group that truly put Harper on the map.

The eventual goal, even from the earliest sessions, was to create the next chapter rather than rehash the hits that brought the fans in. Call It What It Is expands on the group's strengths, moving seamlessly between genres without a hint of irony or lack of conviction. The opening track, “When Sex Was Dirty," combines socially aware lyrics with a sing-along chorus, syncopated riffs, and a classic rock staple: the cowbell. “Outside the studio with the door closed, that cowbell would have still been too loud," says Harper. “That thing was cutting through every microphone." With “Shine," the bands tackles a modern Stax vibe stoked by keyboardist Jason Yates' infectiously perfect Rhodes grooves. And the varied beat goes on, with the Tom Waits-turns-country feel of the dark title track—a meditation on killings by police—and the garage-rock grind of “Pink Balloon."

Overall, the Innocent Criminals—which also includes percussionist Leon Mobley, bassist Juan Nelson, drummer Oliver Charles, and guitarist Michael Ward—is a rare musical outfit that is truly greater than the sum of its parts. The genre-hopping Criminals are simply true to themselves. “We don't have 10 songs of one genre; I never have," allows Harper. “When it's time to make a record, I have written songs in different styles whether they be blues, punk rock, soul, funk, or folk." During preparations for his 2016 tour, we caught up with Harper to discuss his life as a songwriter, how legendary amp guru Howard Dumble helped him discover his tone and tune up his pinball game, and why the Innocent Criminals have become his most effective creative outlet.

What was the vibe like back in '08 when you decided to take a break from the Innocent Criminals? Did you feel that era had run its course?

Yes. We hit a point with each other, with the music, with the creative process, that required us to get some distance from everything so we could actually see what it was that we had and were doing or not doing. But there was a little bit of personal running-in-place. It is hard to … How can I put this? It's hard to grow while you're not actually recognizing what you are growing towards. They are such monster players as well. I just think we had reached a point where maybe we were creating barriers for each other and not creating open roads and opportunities creatively.

Do you think it was more musical or personal?

I think it was both. There was some taking each other for granted and that's where it's hardest to grow. There was no other way but to take time off. I never said, “I am breaking up the Innocent Criminals." It was just time for all of us to do something different. It sure felt like a break-up, but it wasn't, and that is why we were able to remain in communication with each other. And it wasn't easy, that's for sure. It haunted me.

Throughout your career you've focused on writing songs for yourself. Obviously, that material is very personal. Have you ever had an interest in writing for other artists?

I mainly write for myself and the dialogues that I've been having with specific groups of people. There's this privilege to be able to grow together through music with people around the world. I feel so lucky for that. I have only written specifically for other artists a couple of times. I wrote a song for Taj Mahal. I wrote a song recently that is coming up on Mavis Staples' new record.

What does it feel like to hear another artist cover one of your songs?

It's the best feeling in the world. It actually makes you feel like a songwriter, which is great, because I do put a lot into the words. Some lyrics may seem deceptively simple, but they are edited down from a lot of pages of ideas. So when you hear someone actually cover one of your songs in the wild, it's just the best. I think any songwriter will tell you that. I have not grown immune to how exciting that is.

Why was it important to you to view this reunion with the Innocent Criminals as a new chapter?

I couldn't do 10 “Steal My Kisses." I couldn't do it. I have never done anything formulaic in my life. Every song and lyric I write, I mean. Every collaboration with the Innocent Criminals strikes as deep as we can. We leave no stone unturned and by the end of the process we are all exhausted. It's all about bringing forward our strongest material and taking risks. We have never played it safe as a band. We have always had polarizing songs and songs that somehow were different in genre, but there was a through-line in the way this band interprets different genres.

With the exception of a holy grail Overdrive Special amp by Howard Dumble, Ben Harper's rig is fairly simple, with a tuner, volume pedal, reverb/tremolo, overdrive, channel switcher, digital delay, and power unit on his pedalboard.

Photo by Adam Keely

This band's ability to fluently and authentically move between genres is remarkable.

It's the songs, man. I have every Ramones record. I have every Dead Kennedys record. Juan is the funk. Leon's roots are Africa, reggae. These are the influences of this band and the songs that we write and the way that we craft music. That is all we are going for. There have been a couple of times where, like the Get Up! album with Charlie Musselwhite, I've gone into my archive of blues material and the timing was right. Same with the Blind Boys of Alabama record [2004's collaborative There Will Be a Light]. Some of them, like the folk record with my mom—that took she and I both digging into our archive of songs in that style to put that record together. I wouldn't have had an entire record of folk music that I could actually publish, that I could be proud of, on my own. It's more about the songs that I have and picking the ones that I feel strongest about regardless of style.

Say for this record, I had 20 songs. We recorded a good number of them until we started to see the ones that were raising their hands the highest and sitting together the best. It's natural selection in the studio. The ones that stand up, stand up proud—and what starts to happen is you get sister songs. There is a song called “When Sex Was Dirty," which is a sister song to “Pink Balloon." There's a song called “Dance Like Fire," and that's a sister song to “Bones." “Goodbye to You" is percussively linked to “How Dark is Gone." All of a sudden, songs start to pair up with each other and that really helps in the sequence. It's a big risk this day and age to make an entire body of work that is eclectic because we are in the era of judging an artist by his song. That has been coming on year by year and now it is more prevalent than ever. Maybe it will be to my demise or maybe it will be my freaking calling card and strength. I am counting on it being a strength and I am counting on somehow people finding it as an entire body of work. Maybe it is just a pipe dream, I don't know.

As strongly as I believe in a body of work, still, it is time that people start honing the art of putting a body of work together. The days of 13-, 14-, 15-song albums are gone. Come up with a tight 10 or 11 songs and I think you will stand a better chance of introducing people to a larger body of work. Setting limits on yourself is a big part of making a record.

Is the hardest part of making an album the self-editing process?

It's so hard with this band, because we get emotionally attached to songs. We had a listening party of maybe 20 people, and Chris Rock was there. The final song on the record is “Goodbye to You." There used to be two songs after that. After that song he said, “That's it. Don't play another song. That's where this record needs to end." He was right. I felt great about the two songs after that, but Chris and Ethan Allen, who co-produced the album with the band, were right. Ethan is really the North Star, and those objective opinions kind of reeled us in.

Did you have songs ready for this album or did some of them come through rehearsals?

I wanted to see what it was going to sound and feel like when we got back together. I didn't want to pick up and just start rehearsing old material. I wanted to pick up where we had all grown to. Everybody got together for a week at the Village [studios] in Los Angeles. I presented a couple of new songs, and the way that the band just leaned into them, working off each other, it was something so different. I knew it was on. I just needed to get all of us in a room and move into that new direction. That week set the stage for the record and having the group back together and really having the time of our lives creatively.

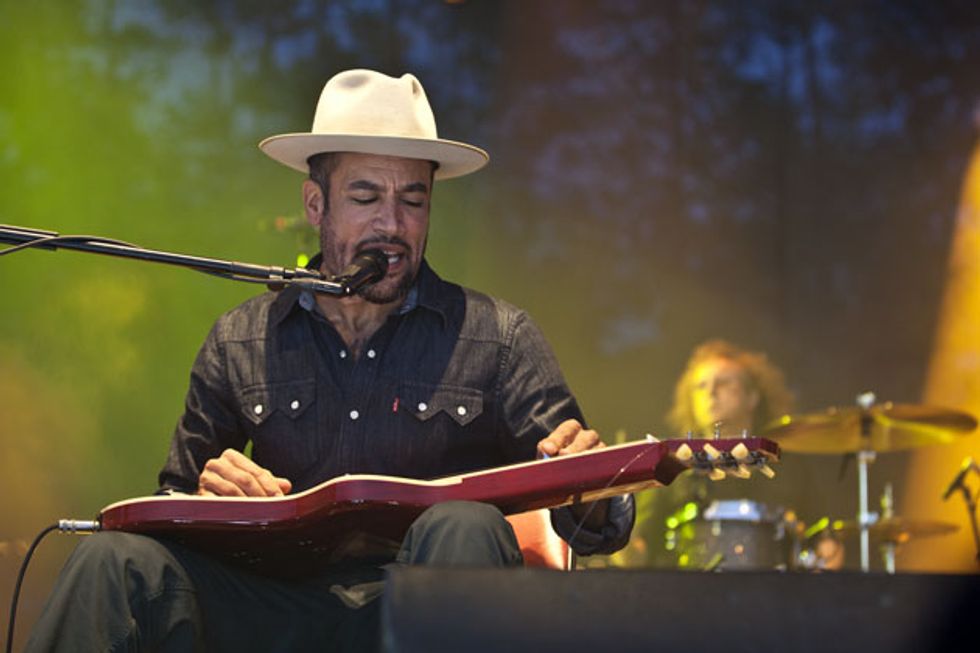

Sitting down on the job is a requirement for Ben Harper, since he's best known for his lap slide guitar playing. But his fiery performances and songs that often explore social issues, like his new album's title track, keep his audience on its feet. Photo by Joe Russo

You spent your formative years around your family's music store in Claremont, California. Did you work on instruments?

I did. I was a bona fide luthier.

Is that something you keep up on?

In a word, no, but I do go out and work in my family's music store quite often, and it's always the best feeling to be back in the shop and having my hands on instruments. It also comes in handy on the road.

The acoustic Weissenborn guitar has become nearly synonymous with your style. Did you stumble upon it at your family's shop?

That was it. We were one of the rare stores that actually recognized them. People used to come in and, because they couldn't fret them, would try to play them like regular guitars. Imagine, in 1958, my grandparents actually recognizing that Wiessenborns were a unique contribution to the acoustic instrument pantheon. David Lindley got his first Weissenborn from my grandfather.

Ben Harper's Gear

Guitars

• Asher Ben Harper Signature Lap Steel

• 2010 Gibson Custom Shop Les Paul Special

• 1954 Fender Hardtail Stratocaster

• Martin HM Ben Harper Special Edition acoustic/electric

• Weissenborn Style 4 Lap Steel

Amps

• 2010 Dumble Overdrive Special

• Fender Princeton

Effects

• Strymon Flint Tremolo & Reverb

• Vox wah

• Hermida Audio Zendrive

• Electro-Harmonix #1 Echo digital delay

• Boss TU-3 tuner

• Ernie Ball volume pedal

• Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 Plus

Strings and Picks

• D'Addario EJ16 Phosphor Bronze Lights (.012–.053; acoustic)

• D'Addario EJ17 Phosphor Bronze Medium (.013–.056; lap steel)

• D'Addario EXL 115 Nickel Wounds (.011–.048: electric)

• Dunlop Picks

• Dunlop Ben Harper Signature Tone Bar

What specifically about that instrument spoke to you?

I don't know. I had every guitar at my fingertips. Although the guitars that I wanted to consider mine, my grandfather made me pay for, so I had to work them off. I've played Dobros, Nationals, Triolians, Duolians, Regals, and all the resonators. Everything from African koras to sitars were at my disposal. There was just something about that freaking Weissenborn. From the time I could hear it, I would just gravitate towards it. Some sounds are out there waiting for the player. Why would anyone want to play the tuba? I don't know, but people have devoted their lives to the tuba. There's a sound out there for everybody and that was the sound for me.

How do you wrestle with the Weissenborns at stage volumes?

I kinda stopped trying to force the Weissenborns up above the band. That's where Billy Asher [of Asher Guitars and Lap Steels] and I co-designed my lap steel. It's a hollowbody with a maple cap, like a Les Paul. It still has this hollow nature, but I don't have to struggle to get over the band. On certain songs I will still crank the Weissenborns up. It's always fun. I make sure I have it out for about a quarter of the set on the blues stuff, like “Homeless Child," “Welcome to the Cruel World," and “Give a Man a Home."

What tunings did you use on the album?

I am all over the map. Mainly versions of open D (D–A–D–F#–A–D) and “Spanish" G (D–G–D–G–B–D). I will take the open D tuning and move it down to C and then I will tune the Spanish G up to A or B. I will even go as high as F on a Weissenborn in the D tuning with lighter strings.

When did you get caught up in the sphere of Dumble amps?

From the time I was probably 9 years old onward, I grew up next door to David Lindley. David's daughter, Rosanne, and I were thick as thieves. Every once in awhile David and his band at the time, El Rayo-X, would have rehearsals at a place called the Alley. David would bring Rosanne and I to rehearsals. I was about 10 or 11 and was at a rehearsal playing the pinball machine. This super-generous dude was giving me pointers on how to shake the machine and how to get the best of it. It was Dumble. He and I first met huddled around a pinball machine. When I started really jumping into tone, would you believe that he remembered me from that? Dumble and I have been at it awhile.

How did you get your first Dumble?

He helped me put out feelers for people who had them for sale and I was able to get my hands on one pretty quickly. Then he actually brought me in and let me plug into his oscilloscope, which he rarely does anymore. He took notes on the frequency patterns of my instruments and he built an amp for the sounds that my instruments make. The only reason he charges so much is because the market has insisted. Otherwise he would charge $5,000 and someone would make $40,000 on his amps. He has no choice. Are Dumbles worth it? You listen to [David Lindley's version of] “Mercury Blues" and tell me whether or not it is worth it.

Are you a big pedal guy? Do you like to tinker with those?

I do, although I'm going for fewer pedals. Charlie Musselwhite will say, “Hey, man. Careful when you are using those pedals and calling it blues [laughs]." He will walk over and glance at my pedalboard and say, “How many of those you gonna use for the blues? How many you need?" So Charlie got me thinking about relinquishing all pedals. For now, it is real simple. I've got a [Hermida Audio] Zendrive, Strymon Flint, Electro-Harmonix delay, and that's about it.

“Finding Our Way" has such an authentic reggae groove. How did you learn about playing reggae guitar? Conceptually, it seems very simple, but it's quite difficult to get the right feel.

That skank. Oh man, it's nasty. First, it's just in me. Second, I have lived reggae music my entire life from Lee Perry and Ernest Ranglin to “Stepping Razor" and “Legalize It" by Peter Tosh. My dad took me to see Marley when I was 10, and it was a life-changing experience. The only way I have been able to illustrate what that skank means is to be in the studio and take it out of the mix. The bottom falls out. It's just this weird, mystic thing. I will never understand why Neil Young's G chord sounds so different than anyone else's in the world. I don't know man; it's the mystery of the guitar. It just pulls you in.

How collaborative is the band in the studio when it comes to creating parts?

This record is credited to the band, as far as production. Everybody was producing. It was magic. You would think it would be too many cooks in the kitchen. I've never been in such an ego-free environment. It made you want to try everyone's ideas even if you thought they were crazy. When someone was driving, like Oliver Charles on those drums, he took the lead. He knew what he wanted, he heard it in his head, and he found it. Sometimes production is patience, but it's also letting people find their way.

Might there be another hiatus in the future?

We won't do that again. There might be a couple of other side projects, but they would be in between Innocent Criminal projects, for sure.

What next thing on your list?

I'm going to leave you with this: instrumental album. [Luthier] John Monteleone. Acoustic lap steel.

YouTube It

Hermann Weissenborn's distinctive guitars are hollow-necked acoustics, and while Ben Harper can make them howl like Hendrix at Woodstock, this solo performance of the socially pointed title track of his new album, Call It What It Is, showcases the instrument's super-warm, amplified natural tone as well as Harper's fearless lyrics.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)