We all know how the Irish saved civilization—and if you don’t know the story, look for Thomas Cahill’s excellent tome on the subject—but what about rock ’n’ roll? From Van Morrison and Them to Rory Gallagher and Taste, or Thin Lizzy to the Pogues, U2 to the Cranberries, My Bloody Valentine to Snow Patrol, Irish rockers have given the British blues explosion a run for its silver, carving out an unbroken line from soul and blues-rock all the way to hardcore punk and ultramod art-rock, and they’ve done it in large measure while hewing close to the staunchly Irish traditions of myth, poetry, storytelling, rebel yells, and romantic longing.

It’s way too soon to refer to the five 20-something lads of Fontaines D.C. as rock saviors (they’d scoff at the prospect anyway), but Skinty Fia, the band’s third slab since their 2019 Mercury Prize-nominated debut, Dogrel, has rapidly turned up the critical heat, going straight to No. 1 on the U.K. Albums Chart upon release. The leadoff single “Jackie Down the Line,” a righteously gloomy but beat-driven rocker, sets the tone for the album, with frontman Grian Chatten transforming himself into the song’s dark narrator (“I will stone you, I’ll alone you”) as guitarists Conor Curley and Carlos O’Connell mesh together in a jangly, echo-laced interplay of crafty three-note chords, 12-string acoustic filigrees, and tremolo-washed sheets of sound. Add the locked rhythm section of Conor “Deego” Deegan (bass) and Tom Coll (drums) behind them, and the band’s tightness, augmented by their dogged desire to keep experimenting, instantly permeates every song.

Fontaines D.C. - Jackie Down The Line (Official video)

“I think when we first met, we were mainly just songwriters,” observes Curley, reminiscing on their early moments together. “I mean, obviously I’m a guitar player, but I saw myself more as a songwriter, and I think the other lads did as well. So the first album was the culmination of trying to be aware of our abilities, and keep things raw and exciting. We were playing 100-cap venues in Dublin, so there was no point in trying to overextend ourselves.

“After that, we felt we had more strings to our bow, in terms of the songs that we knew we could do. We went down more of an introspective path, and definitely got into more psychedelic music with the second album [A Hero’s Death]. And now it’s just a combination of all that. I think something that defines us as a band is that we never want to sit still in a sound. We’re always trying to be inspired by different things.”

Fontaines D.C.’s three albums were all produced by Dan Carey. The band’s first two albums were recorded at Carey’s London home studio, but for the third, Fontaines decided on a change of scenery, opting to record Skinty Fia at Angelic Studio in the English countryside.

The band also stuck with producer Dan Carey (Black Midi, Geese, Wet Leg, and plenty more), graduating from Carey’s home studio in London, where they recorded their first two albums, to the larger Angelic Studio complex in the idyllic English countryside, near Oxfordshire. But before they even took up residence, each band member made the most of the prolonged pandemic lockdown to flesh out detailed demos, either working in Logic or with handheld recorded snippets of vocals and guitar. Armed with well-prepped songs and the prospect of working with Carey in entirely new surroundings, as O’Connell describes it, opened up possibilities that led to a bigger, more multi-layered sound.

“What I love about Dan is his process is in two stages,” O’Connell says. “We were in a bigger studio this time, so he wanted to take advantage of that. There’s the live guts of the recording [from the floor], and that’s just getting the sound right at the start. We spent a couple of days gaining up all the inputs, so when it hits the desk, it’s pretty much a very balanced mix. Then it’s just about playing well and having the songs arranged properly so they work.

“The first album was very much in a fighting mode, with the two guitars EQ’ed the same and just smashing off each other. On the second one, we learned to play together a little better.” —Conor Curley

“And then at the second stage, we do overdubs. We rarely add new parts, but we’ll redo the parts we have, either with a different instrument or treated differently.”

Both Curley and O’Connell also brought some of their earliest influences to bear, including the slashing surf guitar leads of the Birthday Party’s Rowland S. Howard, along with the snakebitten Fender Mustang kick of Kurt Cobain. “We also played a bit more with a blend,” O’Connell says, “like what happened with rock and roll and electronic music in the ’90s, you know? Primal Scream, Death in Vegas, even U2 went through that phase, but they all used actual synthesizers and drum machines. Our idea was to make it sound like that with our own instruments.”

Carlos O’Connell’s Gear

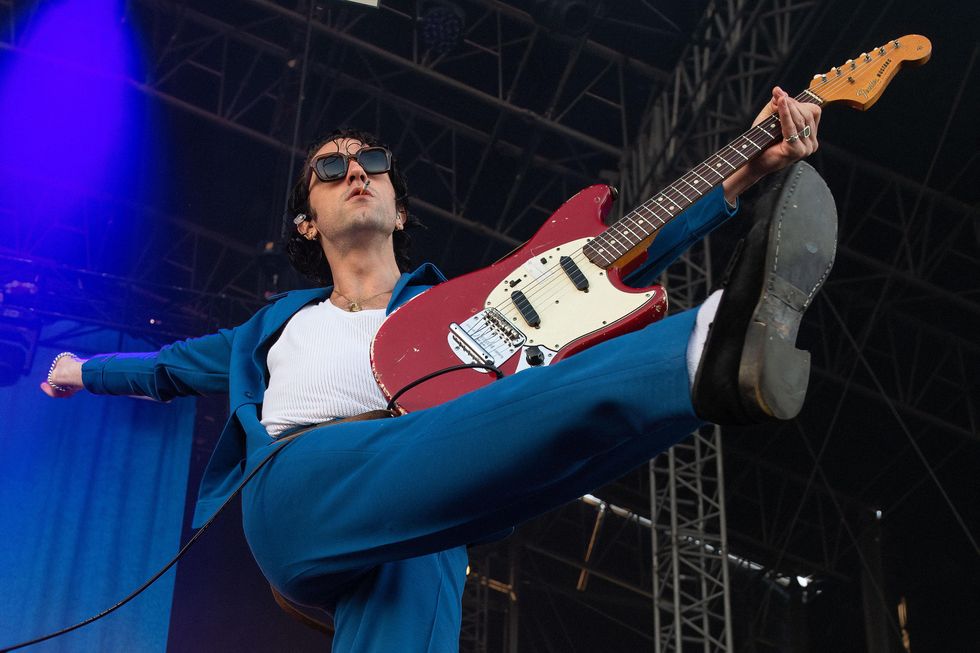

Carlos O’Connell bought his ’67 Fender Mustang online without knowing it was a 3/4-scale smaller model, but it’s become one of his main road warriors.

Photo by Simon Reed

Guitars

- 2019 Johnny Marr Jaguar

- ’67 Fender Mustang 3/4 scale

- 50th Anniversary Fender Jazzmaster [prototype]

- Martin J12-15 with L.R. Baggs M80 active humbucker

- Seagull Artist Studio 12 Burst with L.R. Baggs Lyric acoustic microphone system

Amps

- Fender ’68 Custom Twin Reverb

- Fender ’68 Custom Deluxe Reverb

- 1975 Fender Deluxe Reverb (used only at Angelic Studio)

- THD Electronics Hot Plate

Effects

- MXR M133 Micro Amp

- Electro-Harmonix Soul Food

- Strymon Lex Rotary

- Moogerfooger MF Flange

- Moose Electronics Cosmic Tremorlo

- Moose Electronics Reverb

- Boss TR-2 Tremolo

- Electro-Harmonix Op Amp Big Muff Pi

- Electro-Harmonix POG

- Boss GE-7 Graphic Equalizer

- Dunlop Volume (X)

- EarthQuaker Devices Life Pedal

- Vein-Tap Murder One Killswitch

Strings & Picks

- Ernie Ball Burly Slinkys

- Dunlop Tortex .60 mm

The album’s title track “Skinty Fia” (roughly translated, “the damnation of the deer”) delivers on the idea. Wielding his trusty ’67 Mustang through Carey’s own ’75 Fender Deluxe Reverb, O’Connell avails himself of a chaotic wash of tremolo (aided by a reverb pedal from Dublin-based Moose Electronics, which he unconventionally places first in the effects chain, ahead of his overdrives) to propel the song’s relentless, hypnotic churn. Meanwhile, in the left channel—throughout the album, each guitarist occupies his own side of the stereo image—Curley knifes into the mix with an echo-drenched melody on his Johnny Marr Jaguar, routed into a Fender Twin Reverb, to accentuate Chatten’s menacing vocal, while Deego and Coll hammer out a beat that recalls Nine Inch Nails with a thick, dub-style low end.

“I think we’re trying to be more patient, and more conscious of the texture,” Curley says, describing how he and O’Connell have worked together to refine their sound. Like most bands with a two-guitar attack (the well-known Irish precedent of Thin Lizzy comes to mind), the symbiosis comes with time, practice, and subtle lines of communication. “The first album was very much in a fighting mode,” he continues, “with the two guitars EQ’d the same and just smashing off each other. On the second one, we learned to play together a little better. We’re still working on it, and sometimes we still try to become as one almost, when the song needs it, but I think now we’ve learned to fit in with how we’re EQing everything. It feels really good.”

Fontaines D.C. - Full Performance (Live on KEXP)

The confidence shines through on Skinty Fia, especially when the two axe-slingers choose to embrace a little sonic chaos. On the dark drum-and-bass-influenced opening track “In ár gCroíthe go deo” (“In Our Hearts Forever”), O’Connell tees up another locked tremolo effect, eventually morphing into an otherworldly chorus effect, mirrored by Curley, of what sounds like distant dogs howling. “It’s only at the end where my guitar comes in,” Curley clarifies. “I’m just following the bass with the chords, at a very high frequency, and with delays at the end of every phrase. I hit my [Industrialectric] Echo Degrader, and that’s what really sends it into a spin.”

On the Curley-penned “Nabokov,” the layers of noise lean heavily on classic shoegaze and dub, with Curley again availing himself of the Echo Degrader. “That pedal is so unpredictable, it’s almost like it doesn’t sound the same every time you use it. I’ve been using that and an RV-7 [by Digitech Hardwire] for gated and reverse reverb. There were definitely a lot more shoegazey elements that we were trying to get to, and, obviously, if you start talking about Kevin Shields or even Robin Guthrie from Cocteau Twins, the stuff they did, to me, is almost unreachable, but if you try, you might end up with something new anyway.”

Conor Curley’s Gear

Conor Curley often toggles between this ’66 Fender Coronado II and a Johnny Marr Jaguar.

Photo by Debi Del Grande

Guitars

- 2019 Fender Johnny Marr Jaguar

- ’66 Fender Coronado II

- Fylde 12-string (loan from Richard Hawley)

Amps

- Fender ’68 Custom Twin Reverb

- Lazy J (used only at Angelic Studio)

- THD Electronics Hot Plate

Strings & Picks

- Ernie Ball Burly Slinkys

- Dunlop Tortex .60 mm

Effects

- Industrialectric Echo Degrader

- DigiTech Hardwire RV-7 Stereo Reverb

- Moose Electronics Reverb

- Moose Electronics Delay

- Strymon Sunset

- Strymon Deco

- ThorpyFX Chain Home

- Electro-Harmonix Nano POG

- Dunlop Volume (X)

By contrast, both guitarists reached for a 12-string acoustic on a pair of songs: Curley on the aforementioned “Jackie Down the Line,” and O’Connell on the smoldering groover “Roman Holiday.” Oddly enough, the Fontaines acquired the guitar, a beautifully finished Fylde custom 12-string, from British crooner and troubadour Richard Hawley, who met the band on a recent jaunt in Sheffield. “We were struggling to find a really nice sound on a 12-string,” O’Connell says, “so it was like, let me just text him. He was really excited about being a part of it and lending us the guitar, and it was magic. Just a beautiful guitar. Someday I’ll get one, but you can never play it live because it’s just too precious.”

And on tour, Fontaines comes across as anything but precious. Chatten often prowls the stage like a wounded animal between verses, wielding the mic stand like a cudgel and seeming to goad the band into wilder forays of sonic exploration. At a recent packed house in Brooklyn, Curley and O’Connell whipped “Too Real,” one of their earliest singles from Dogrel, into a feedback-laden, psych-rock deluge, while an encore of “Nabokov” made the most of the dueling washes of noise that each guitarist can deliver, with precision, from either side of the stage. As a unit, they’re brash, tough, and confident—typically young, and typically Irish.

Carlos O’Connell utilizes his prototype 50th Anniversary Fender Jazzmaster when he’s going for a deep, low-end guitar tone.

Photo by Tim Bugbee

“We’ve found refuge within each other, and within our identity,” O’Connell observes when asked about the band’s recent, and inevitable, move to London. Chatten in particular, as frontman and lyricist, has been outspoken in interviews about some of the prejudices he’s encountered, a sentiment that inspired the song “In ár gCroíthe go deo,” which pays tribute to an Irish woman in Coventry who was initially denied permission to bury her late mother with the Irish inscription on her gravestone.

“We also found that accumulated frustration with a very ignorant misunderstanding of Ireland from Britain’s point of view, which started to piss us off quite a bit,” O’Connell reveals. “But then we wrote this album, and ever since, it’s starting to open up a lot. It’s given me the dream of what I thought I would find in London: a place where we’re more anonymous and where there’s less expected from us, you know?”

“We were struggling to find a really nice sound on a 12-string, so it was like, let me just text him [Richard Hawley].” —Carlos O’Connell

Surely those expectations will grow in urgency as time goes on, but for now Fontaines D.C. seems content to ride the lightning. “There’s been a lot of self-discovery along the way,” Curley says. “There’s always inspiration to be found in Irish art and culture, and we’re also massively into Irish traditional music. Me and Tom got really into Paul Brady and Andy Irvine and Planxty, and we wrote a good few Irish ballads. At one point, we actually thought of doing Skinty Fia as a double album, which I guess might’ve seemed a little gratuitous. Hopefully those songs will see the light of day in a different context.

“But now that we’re back on tour, whatever happens, I think we’re definitely not gonna take any of it for granted. We’re just trying to enjoy all the things we see, and trying to put on really good shows.”

YouTube It

In this pandemic-era livestream, Fontaines D.C. plays a half dozen songs from their Grammy-nominated sophomore album, A Hero’s Death [2020].

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.