"You know, you go into a venue and you're like, 'I know what this place is going to sound like.' Within seconds of hearing the room, you're making adjustments and rolling with the punches of whatever space you're in," explains singer/songwriter Liam Kazar. "That, I feel like, I've definitely taken into food."

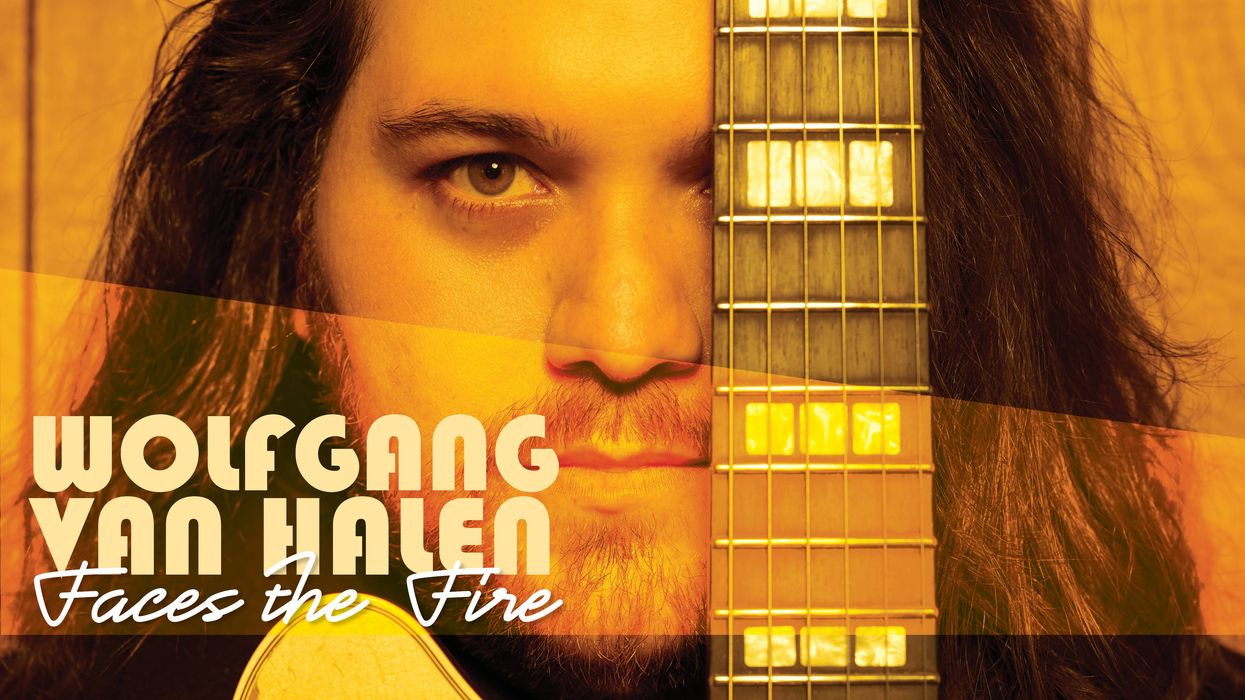

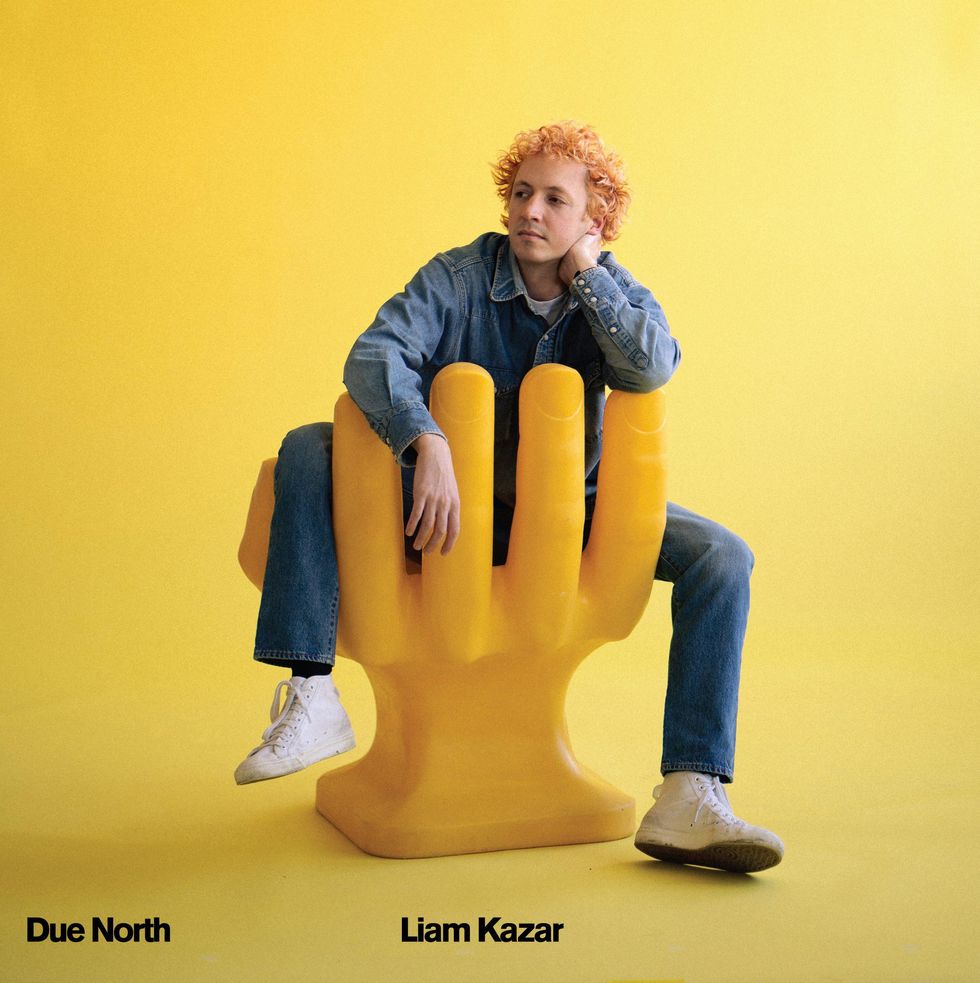

When we spoke, Kazar was in the middle of a big 2021. After years on the road as a side musician for artists such as Jeff Tweedy and Steve Gunn, and as a member of the bands Kids These Days and Marrow, he was about to strike out on his own with Due North, his debut solo record.

Due North is an excellent showcase of Kazar's preternatural songwriting. The dry and bouncy groove of "So Long Tomorrow" kicks things off, driven by tight acoustic guitar and funky electric piano, with Kazar's plainspoken voice offering moody counterpoint. Within a couple tracks, it's easy to parse out such influences as Bowie, David Byrne, and George Harrison, all strong flavors that are a feat just to evoke. But what makes Due North an impressive accomplishment is that these sounds never overpower Kazar's own vision. Instead, they coalesce to form the kind of musical whole that is rare on a debut and is surely evidence of great things to come.

Liam Kazar - Frank Bacon (Official Music Video)

But Kazar recently found a new creative outlet and business opportunity when, faced with the early pandemic's dearth of gigs, he turned to his lifelong love of cooking. After taking a culinary deep-dive into his Armenian heritage and cooking his way through recipes found in books and on YouTube, the songwriter wanted to share his food outside of his home. With some posts on Instagram, his Kansas City kitchen quickly became one of the best kept secrets in the culinary world. "I had this ethos of 'I am not waiting for shit to come back. I'm gonna stay right here, right now,'" he says. "The idea of cooking out of my house and selling meals seemed like a good use of my time. I announced it on Instagram in January as a casual thing."

Named Isfahan—after the city in Iran and his favorite Duke Ellington tune—Kazar's side-project quickly became its own dedicated hustle. When the Chicago Eater took notice, business exploded. "I was thinking I would do it just to stay busy and break even, and that went crazy from there," he says. Isfahan has since appeared in The New York Times Style Magazine, and, thanks to this attention, started travelling around the country to run pop-up food events.

I can't work on music at all when I'm doing cooking stuff, which is a bummer, because I'd like to be able to do a couple hours here, a couple hours there.

This is the kind of recognition that a chef could build a successful career on. But when we talked, Kazar had just finished up a series of events in the Northeast and was re-focusing on music in preparation for the release of Due North. It's not that he's hanging up cooking. He'll be back at it shortly. Kazar is simply an artist who has learned his limits and knows that a single-minded focus is what has made both his music and food so special.

"I can't work on music at all when I'm doing cooking stuff, which is a bummer because I'd like to be able to do a couple hours here, a couple hours there," he says. "That's why I would never even consider brick-and-mortar with the cooking thing, because I know I'd never write a song again. I have to do self-imposed breaks with cooking."

Deep Roots and Pragmatic Concerns

The story of Due North stretches all the way back to Kazar's roots growing up in Chicago. He lived around the corner from the Tweedy family and became friends with Spencer Tweedy at around age 10. Since then, he has been close with the Tweedys and even spent time living in their house. Back in high school, when the young songwriter formed Kids These Days—an eight-piece unit where he played R&B-style rhythm guitar and served as lead songwriter and vocalist alongside fellow Chicago music scene up-and-comer Macie Stewart [now of Ohmme]—Spencer's dad, Jeff, served as a mentor and helped the band with recordings.

TIDBIT: Kazar recorded Due North at Foxhall Studio, which is run by his sister, Ohmme's Sima Cunningham, and her partner, Dorian Gehring. Kazar says, "I mostly engineered the record. I would do a bunch, it would get messy, and Dorian would come in and make it nice and neat and fix it all up. Spencer [Tweedy] did a lot as well, particularly miking his own drums."

Jeff went on to hire Kazar to play guitar and keys in the band Tweedy—which includes Spencer on drums—and took him on the road, where he gained loads of inspiration and learned deep musical lessons. "Jeff's acoustic guitar playing, his rhythm guitar playing, is a big influence on me," Kazar shares. "The whole song is there in his guitar and everyone's just sort of hopping onboard. The engine is his right hand. Spencer is so tuned into Jeff's right hand. He has live solo arrangements and you figure out how to fit into that. Don't worry about what's on the record. It's a whole thing that he's figured out how to translate live and you figure out how to fit into that. That was a huge influence on me—watching how he builds the song on acoustic guitar."

Tweedy helped Kazar begin to conceptualize just what his solo music should sound like. "When I started thinking about making a solo record, Jeff pointed out to me, 'It sounds like you're writing for other people and you're not writing for yourself,'" he details. "That was a huge moment of, 'Oh shit, I need to go figure out who I am,' so I could write for myself."

Jeff's acoustic guitar playing, his rhythm guitar playing, is a big influence on me.

Kazar estimates that process took about a year-and-a-half of considering the possibilities as he waded through a bevy of influences, from various country artists to Al Green's The Belle Album to Bowie's Berlin Trilogy. This seemed like an overwhelming task at first, but he found help close at hand from fellow Tweedy band member James Elkington, who would go on to produce the album.

Kazar explains: "After the show, Jeff might hit the hay or whatever kind of quickly, and he [Elkington] and I would start talking. He was just so invested in whatever I was trying to do." These talks helped the young songwriter suss out how to navigate his inspirations and successfully find his own voice.

Liam Kazar's Gear

Kazar's go-to electric is an early 2000s Tele, souped-up with a pair of Seymour Duncans and a Bigsby, which he pairs with a simple set of pedals and a Fender Deluxe Reverb.

Photo by Hannah Sellers

Guitars

Amps

- Fender '65 Deluxe Reverb Reissue

Effects

- JHS Colour Box

- MXR Carbon Copy

- Xotic EP Booster

Strings and Picks

- .010 sets on electric, no brand preference

- .012 sets on acoustic, no brand preference

- Dunlop 1.0 mm Tortex picks

Another big inspiration was a practical lesson from his experience as a side musician. "I have done so many one-offs where I'm playing people's music where they flew into town and they need a band and I need to get 15 songs in my head with one rehearsal," he says. Kazar realized that as a young solo artist, his own roster of collaborators could be in constant flux, so he chose to leave space in his songs for musicians to contribute their own voices, which meant not overwriting or over-arranging. "I should be able to show anyone a song in one minute," he explains. "There's a couple tunes that are a little annoying to get right. But 90 percent of the record, I can talk you through the song in a minute."

Simple Ingredients

Kazar's voice and songwriting take center stage on Due North, but his guitar playing really helps sell it. "The stuff that piques my ear on records now is really oddball rhythmic guitar playing," he enthuses, noting that his favorite player these days is longtime Bowie guitarist Carlos Alomar. "I'm always looking at what he's doing. I respect the Fripp stuff and the Adrian Belew stuff, but it's not who I am. I'm trying to be the lead singer. I find it much more valuable for me as a songwriter to deep-dive down what Carlos Alomar is doing with a two-chord song. He's an incredible guitar player and everything he did from Young Americans through Scary Monsters is my peak R&B style guitar playing."

I find it much more valuable for me as a songwriter to deep-dive down what Carlos Alomar is doing with a two-chord song.

For his own funky electric guitar sound, Kazar uses an early-2000s Mexico-made Tele with a Seymour Duncan P-90-style pickup in the neck and a Seymour Duncan Tele bridge pickup, and a Bigsby. His signal chain is simple and most commonly includes only an MXR Carbon Copy and a JHS Colour Box, which he employs for leads on songs such as "Shoes Too Tight" and "So Long Tomorrow." He keeps an Xotic EP Booster nearby, which he calls a "contingency plan if I can't get my amp to sound right or if my amp is having a bad day, as they do. I'll just set that right and leave it on the whole show."

For practical reasons, Kazar uses a Fender Deluxe Reverb. "At some point, I was like 'This is the amp that people are handing me anyway, so I might as well learn how to use this thing,' and that's what I did, and I love it. I know how to get the Deluxe to do what I want to do."

For live shows, Kazar keeps his gear as simple as possible, down to the mic stand. "I started using a straight stand," he says, and adds that it allows him to go "as far to the front of the stage as I can."

Photo by Alexa Viscius

He cites Al Green's guitar playing on The Belle Album as the inspiration for much of the acoustic work on Due North. "The acoustic at the beginning of 'Shoes Too Tight' or all of that chugga-lugga stuff that I'm doing on a lot of the songs—that was me trying to mimic that sound." For that sound, he reached for a Yamaha FG-110E, as well as a Martin 00-18 for "the country folk sort of vibe" on the songs "No Time For Eternity," "I've Been Where You Are," and "On a Spanish Dune." Live, Kazar uses a 1971 Gibson LG-1 that he's owned since he was 14 years old, although it didn't make it onto the record. "It's still what I write everything on," he notes, "it just doesn't record the way I want it to for that sound, so I don't use it in the studio, but I'll use that live."

This refined set of tools allows Kazar to focus on the things that matter most while performing and recording. "It comes from wanting to be the lead singer guy in the band. That's what I want to be doing with this solo stuff. That's the goal: to focus on me singing to the audience, and the guitar playing, the gear, is all out of sight."

For Kazar, keeping things simple and having an open mind fuels the creative process—and if there's one thing that applies to all parts of his creative life, musical or culinary, this seems to be it. "A recipe is essentially an idea. A song is also an idea, or at least that's the way I think about them," he muses. "I feel like I respect that fact by allowing myself to be surprised by a dish based on what oven I'm cooking it in or what prep cook prepped it with me—what their skill set was. That's really similar to a song that you're playing with some new musicians, and just letting it be what it is, and finding the beauty of that."

“Shoes Too Tight” by Liam Kazar - Union Pool, Brooklyn, NY, August 31, 2021

This bouncy trio version of "Shoes Too Tight" has it all: tight but airy grooves courtesy of a well-tuned and responsive rhythm section, and searing, tasteful leads from Kazar's Rickenbacker.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.