Do-it-yourself recording is a great musical tradition. Machines for capturing sound were available for home use as early as the 1930s. Famously, in the late ’30s and early ’40s, ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax, a lover of folklore and American music, followed in the footsteps of his father, John Lomax, and drove a 1935 Plymouth sedan across the United States with some tapes and a recording machine in the trunk. In August 1941, he captured musicians on their front porches and in living rooms across the American South, including one 28-year-old McKinley Morganfield—better known by his stage name, Muddy Waters. When Waters heard himself on tape, he was deeply moved. “He brought his stuff down and recorded me right in my house, and when he played back the first song I sounded just like anybody's records,” Waters told Rolling Stone back in 1978. “Man, you don't know how I felt that Saturday afternoon when I heard that voice and it was my own voice.” Lomax’s field recordings (trunk-recordings, perhaps?) are a significant jewel in the American Folklife Center’s treasury at the Library of Congress.

The apartment-ready 4-track tape recorder changed the game in the ’70s, then the next decade’s digital advancements blew the doors clean off the studio system. Suddenly, artists could handily create their own recordings from home, and they weren’t half bad. Check out Morphine’s 1993 radio hit “Cure for Pain,” for an example. The horns were recorded on a 4-track in frontman Mark Sandman’s Cambridge, Massachusetts, loft. (Listen closely and you can hear the effect the slightly stretched tape had on their sound.)

“They were really experimenting with unorthodox recording techniques to get previously unheard sounds onto records, and you can still incorporate that philosophy into digital recording.” - Rich Gilbert

As time went on, some went all-in. Venerated alt-rock outfit Deerhoof, who had used a 4-track to record their 1997 album, began making records with laptops and Pro Tools starting in 2000. “It seems like you can either go to a medium- or high-budget studio for one day, or you can use the equipment you have or can borrow from friends, and do it as long as you want,” drummer Greg Saunier said in a 2006 interview. “I realized there was no comparison—the time was so much more valuable than the fanciness of the equipment.”

Home recording equipment for guitarists has basically moved at the speed of light since 2006, and now many of the pros don’t even leave the comfort of their own nest to lay down award-winning tracks. There are plenty of reasons for that (besides the ability to do it in your pajamas). Recording your own guitars in your own space can be incredibly empowering: It’s an exercise in self-sufficiency and independence, both of which can be rare commodities in the world of recorded music. Perhaps most importantly, it doesn’t require a stack of cash to get recordings that you like.

“Sometimes, recording in a DAW, it can sound like you’re on top of the music if you’re recording in a collaboration.” - Ella Feingold

Of course, there’s a spectrum of approaches. Some rely on big-money gear to get the job done, but just as many will swear by cobbling together a home-brew sound setup that matches the project. And besides, it’s not all about the equipment. Recording guitar parts on your own in your dwelling is a unique process with its own complexities, not all of which can be captured and explained in instructional YouTube videos. That’s where battle-tested insights come in handy.

So, I asked three guitarists—a studio heavy-hitter to the stars; a “legendary” long-time independent punk; and an alt-rock up-and-comer—how they cut record-worthy 6-string tracks at home. Here’s what I learned.

Ella Feingold

Flanked by records from Tangerine Dream and Vangelis, Ella Feingold clutches her home studio’s secret weapon: a ’60s Maestro EP-2 Echoplex.

When Ella Feingold started recording at home in 2002, the Digidesign Digi 001 was the tech of the day. Feingold always wanted to figure out how guitar parts and overdubs worked together, be they on a Barry White record or a Motown guitar section, so she set to recreating those layers with the recording system. It wasn’t long before she was working on overdubs for other artists with her new rig, and the practice turned into a career. Now, she’s known for her work with Silk Sonic, Questlove, and Erykah Badu, and on Godzilla: King of the Monsters.

Feingold began her career when everyone still gathered in the studio and recorded to tape, so she’s familiar with the feeling and energy of creating something together rather than in isolation. The key to avoiding Lone Musician Syndrome, she says, is to find a way to get inside the music rather than playing on top of it. “Sometimes, recording in a DAW, it can sound like you’re on top of the music if you’re recording in a collaboration,” she says.

There are technical remedies for this, like plugins and impulse responses (IRs) that can help mimic atmosphere or certain room sounds. But there’s a philosophical angle to it, too. When Feingold gets a project, she first listens to it over and over with no instrument in her hand. The idea is to rein in your instincts. Sometimes, they’re helpful. But other times, they let you drift to familiar sounds, progressions, or timings. Feingold will jot notes based on what pops into her head on those first listens, but only later will she pick up a guitar to arrange a part, and see how those initial reactions actually fit with a patient, considered read on the music.

Ella Feingold's Home Studio Gear

Guitars

- 1981 Gibson ES-345 Stereo

- 1967 Vox Super Lynx

- 1967 Goya Rangemaster

- 1950’s Kay Thin Twin

- 1981 Ibanez GB10

- Fender Nile Rodgers Hitmaker Stratocaster

- 1972 Fender Telecaster

- Fender MIM Stratocaster (strung for inverted tuning)

Amps

- 1966 Fender Princeton Reverb

Effects

- Maestro EP-2 Echoplex

- Maestro Boomerang BG-2 Wah Pedal

- Maestro PS-1A Phase Shifter

- Maestro FZ-1A Fuzz-Tone

- Maestro FSH-1 Filter/Sample Hold

- Zoom 9030

Interface, Mics, and Monitors

- Acme Audio DI WB-3

- BAE 1073

- Ableton Live

- RCA 77-D

- Electro-Voice 635A

- Yamaha NS-10

- Dynaudio BM-15

Feingold’s biggest gripe with home recording is engineering for herself. When she records direct into her interface, it’s no issue, but miking, listening, and tweaking mic position ad infinitum is a major drag—especially if a client has revisions on your work. Say you recorded a lead part in 8th notes, and they tell you a week later that they want a portion of it redone in 16ths. If you recorded those parts on a miked amp, there’s a good chance it’s not set up the same way anymore, and you’ll spend a nice chunk of time replicating the exact sound you got the first go-around. “If I could, I would never engineer for myself,” she groans.

Feingold lives in the mountains, so background noise isn’t a concern these days, though she uses the Waves NS1 plugin for apartment dwellers looking to erase unwanted background from their recordings. But what’s her biggest piece of advice for guitarists recording from home for someone else’s projects? Communicate. “Ask them what their expectations are of you,” she says. “It’s always important to know who you’re working with. By asking, it allows you to help them and not waste your own time.”

Finally, if you’re miking your rig, Feingold suggests checking out good preamps for everything you record. They can add something to the signal that will make your life easier at every turn down the road. “Getting ‘the sound’ before it touches the computer is really where it’s at,” she says.

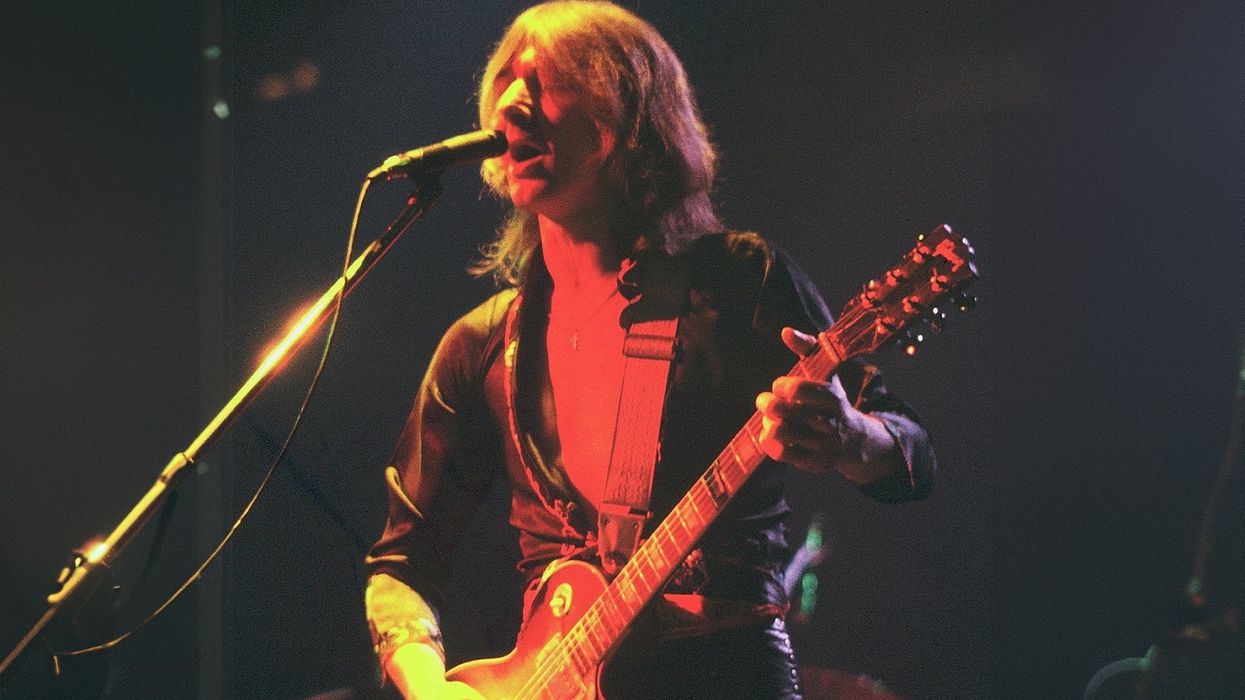

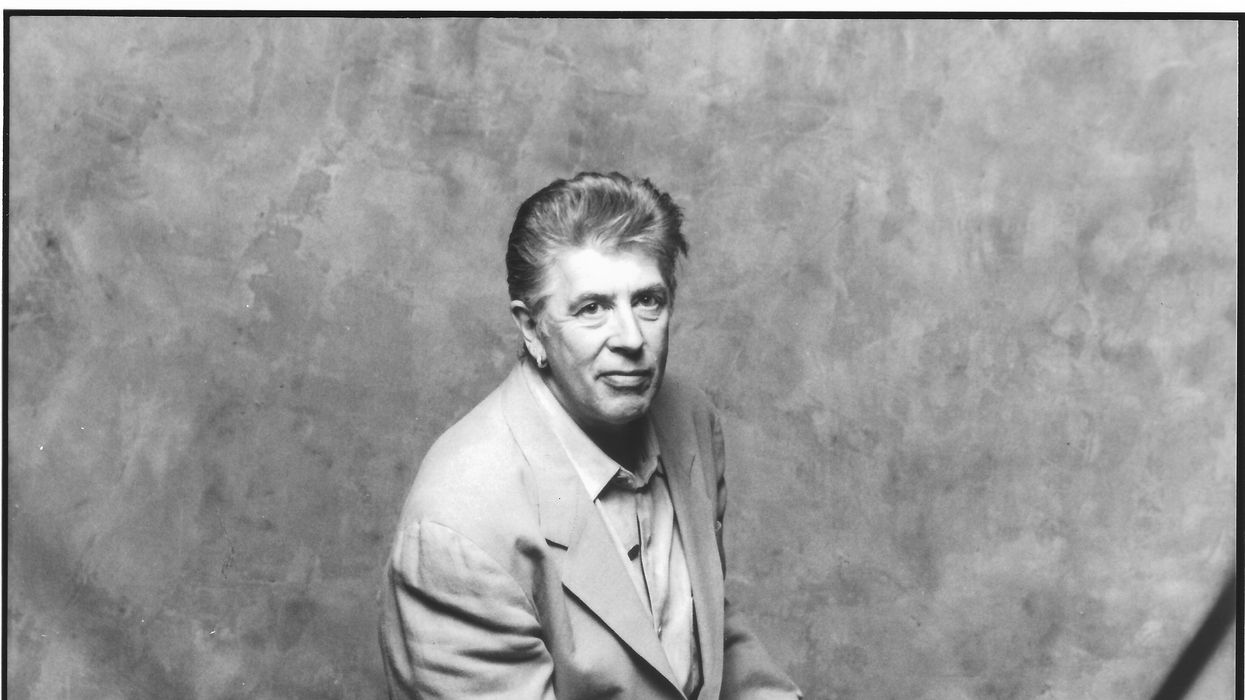

Rich Gilbert

Lifelong DIYer Rich Gilbert sold most of his home studio gear last year, but with just a couple key pieces, he can still cut album-ready tracks from his new casa in Italy.

Photo by Liz Linder

Home studio whiz Rich Gilbert sold off most of his recording toys when he moved from Maine to Italy in late 2023, but he’s cool with it. All he needs these days is a good laptop with Logic Pro, an interface, and some half-decent nearfield speakers to get comfy with. He records most of his guitars direct these days, and writes and programs his own drums in EZdrummer.

Gilbert has been playing in rock bands since the late ’70s, including Boston art-punks Human Sexual Response and the Zulus, Frank Black and the Catholics, and Eileen Rose (whom Gilbert married). He always loved recording, and soaked in everything he could learn when his bands were in the studio, even if it meant pestering the engineer a little. When Pro Tools became affordable in the early 2000s, he loaded it up with a rackmount interface and MacBook Pro. He devoured issues of Tape Op magazine and started building up his collection of microphones and plugins. He still doesn’t call himself a pro, but that’s part of the point. “This whole digital recording revolution is fantastic in that it enables people like me to make good-sounding records,” he says. “At the same time, it’s kind of a cheat because I don’t really have to know as much.” Over the past 20 years, Gilbert has home-recorded LPs for his solo project, Eileen Rose, and his old band, the Zulus. He also has a practice of cutting tracks for indie artists—for one example, St. Augustine, Florida’s Delta Haints—at $75 per song.

Rich Gilbert's Home Studio Gear

Guitars

- Peavey Omniac JD

- Amps

- Line 6 POD Farm

Effects

- Slate Digital plugins

Interface, Mics, and Monitors

- Pro Tools

- Mackie HR824

- Line 6 POD Studio UX2

- Shure SM7

- Shure SM57

- Shure SM58

- Audio-Technica AT2020

- Audio-Technica AT2035

- Blue Spark

- Monster Power PowerCenter PRO 3500

Gilbert says any aspiring at-home engineer ought to go right to the source for solid information. Study how other engineers have recorded things through history. If there’s a particular sound or feel you’re going for, look at the equipment used to capture it. These days, chances are good that basically any piece of gear you’d lust after has been turned into a plugin.

“Read as much as you can,” says Gilbert. “Read interviews with other engineers as much as you can, ’cause you’ll learn.” In Gilbert’s decades of reading and research, he says he’s seen one sentiment crop up again and again: There is no right or wrong way to do it. “All these things we do are just techniques that someone else did, and then passed it on to someone else,” says Gilbert.

That ethos, he explains, actually comes right from the 1960s and ’70s golden recording era that most of us are trying to ape. “They were really experimenting with unorthodox recording techniques to get previously unheard sounds onto records, and you can still incorporate that philosophy into digital recording,” says Gilbert. “Don’t be afraid to experiment. If it sounds good, it is good.”

That said, another important piece is to know when to walk away from a session. If every frequency seems to be just out of whack with your ears, there’s a good chance you need a break. Remember: At home, you’re juggling the jobs of guitarist, engineer, and producer, and sometimes, the producer has to tell the guitarist to take a walk and come back with a fresh perspective.

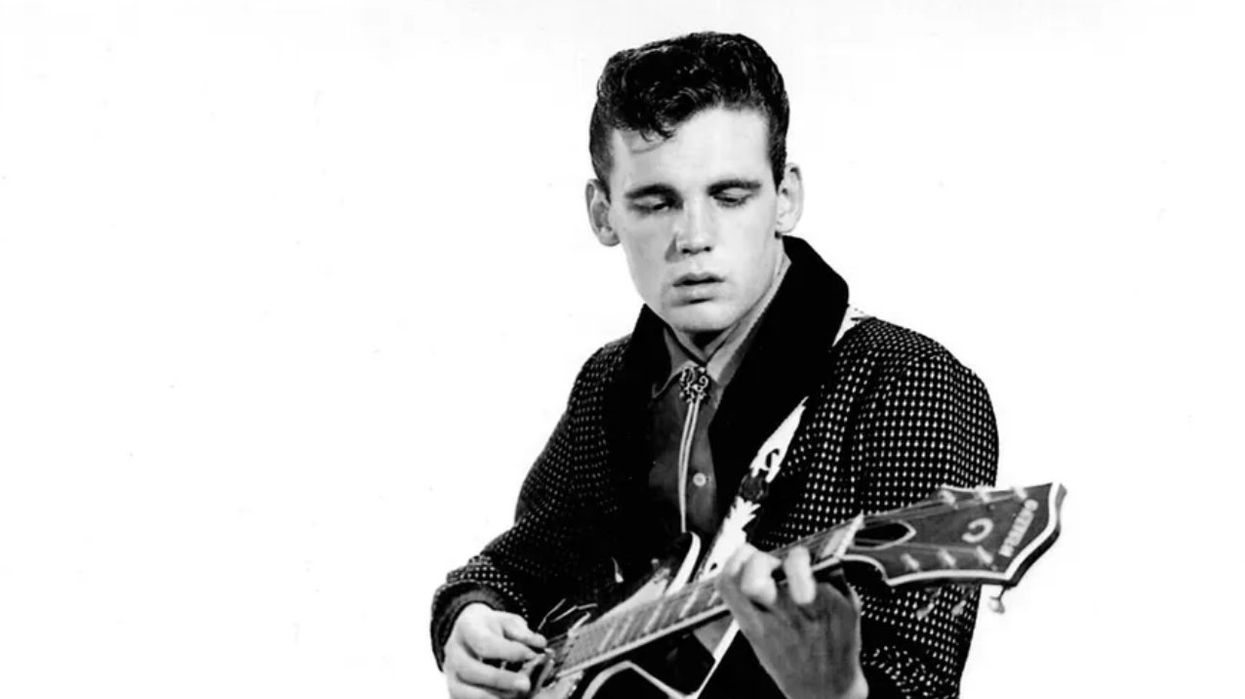

James Goodson

James Goodson launched his home-recording project Dazy as an outlet for his “demoitis,” and his song “Pressure Cooker” exploded into an alt-classic.

Photo by Chris Carreon

James Goodson never meant for his band Dazy to be a home-recording project, but after years of tinkering in GarageBand, he’d gotten attached to the rawness of the demos he made with drum machines. During the great shutdown of 2020, he decided to release them into the wild. Now, his single “Pressure Cooker,” a collab with the punks in Militarie Gun, has racked up more than 500,000 streams.

Goodson says he’s not a technical person, so he tries to keep it simple and trust his ears. “If something sounds cool, then that’s that,” he says. “I’m not worried about ‘the right way’ to arrive there.” After almost 20 years on GarageBand, he recently switched to Logic, into which he runs his 4-channel Behringer interface. He uses two mics—a Shure SM57 for his vocals, and a Sennheiser e 609 for recording guitars. He prefers the 609 for its simplicity: Slap it right flush with the grille and start playing. It’s usually on a Vox AC15C1, but Goodson’s secret weapon is a lineup of battery-powered pocket amps that sound “truly wild” when cranked. This combo is how he achieves most of the lush, varied guitar sounds on Dazy’s recordings, with the odd “weird DI tone” in the mix as well. “There’s something cool about the tones from a real amp colliding with some wack digital tone,” he says.

James Goodson's Home Studio Gear

Guitars

- Fender Vintera ’60s Jazzmaster Modified

- Fender MIJ Telecaster

- Fender Marauder

- Fender Highway One Jazz Bass

- Fender Villager 12-String Acoustic

Amps

- Vox AC15C1

- Fender MD20 Mini Deluxe

- Fender Mini ’57 Twin-Amp

Effects

- Electro-Harmonix Big Muff

- Electro-Harmonix Op Amp Big Muff

- Behringer SF300 Super Fuzz

- Big Knob Pedals I.C.B.M. 1977 Op Amp Muff

- Permanent Electronics Silver Cord Fuzz

- Electro-Harmonix Soul Food

- Boss SD-1

- Seymour Duncan Shape Shifter

- MXR Phase 90

- MXR Micro Chorus

Interface, Mics, and Monitors

- Behringer U-Phoria UMC404HD

- Sennheiser e 609

- Shure SM57

Goodson says his biggest challenge is managing volume levels. Feedback, for example, is difficult to capture unless you push an amp to its limits, which generally involves a lot of noise. Space is limited at Goodson’s house, so he’s generally in close quarters with that squall for extended periods of time. “Thankfully, my wife is incredibly patient about the racket,” he says, “but I’m not sure if my ears are as flexible.”

“There’s something cool about the tones from a real amp colliding with some wack digital tone.” - James Goodson

Those downsides do have proportionate offsets, though. Goodson says the creative process that one can chase at home is incomparable to its studio counterpart. This ultimately comes down to time and money. “I love being able to just sit around for hours rearranging pedals in search of the ugliest fuzz or playing a part over and over trying to make the screechiest noise—the kind of thing that no one is gonna want to put up with when you have two days in a studio to record ten songs,” he says.

Pushing the boundaries of good taste is one of the sweet joys of life, but Goodson says it's important to know your limits, too. When recording at home, it’s critical to know when to tag in help, he says, and he always sends off his tracks to be mixed by a professional engineer.

The Wrap-UP

There’s a lot of technical overlap between how Feingold, Gilbert, and Goodson work, but the crucial thing they all have in common is reverence and excitement for whatever they’re playing on. Recording guitar from home works best if you really, deeply care about the sounds that you’re creating—even if they’re not for your own projects. Getting the best possible result out of your stay-at-home studio is a matter of experimentation, patience, and genuine respect for the music. You don’t have to drop big money to get those things, but you do have to practice at them. If you ever get frustrated with the process, just remember: Being a work-from-home guitarist is a pretty sweet gig.