About halfway through my call with Steve Vai, I’m brimming with enthusiasm and feeling energized and inspired. Sure, it’s fun to talk to Vai—he’s a hero to so many of us, so it’s naturally exciting—but there’s more to this: He’s giving me a motivational pep talk.

“There’s a huge secret,” he says, and I’m all ears. “Everybody is inspired within themselves with unique ideas that are perfectly suited for their unique creativity in the world. That is within everybody. When you receive that inspiration accompanied with the feeling of enthusiasm and the belief of ‘I know I can do this, I just gotta put the time in,’ that’s an inspiration that’s tailor-made for you and there’s no way that it’s not gonna happen. The universe gave you that so that you can manifest it. That’s what it wants you to do.”

This empowering rap comes with a warning though: “Unfortunately, a lot of people don’t find it because their minds drift into fantasy about the future and basically create these fictional desires that are impractical and not really right for you. It’s like people saying, ‘I want to be a world-class virtuoso guitar player,’ but they have a completely tin ear. It’s like me saying, ‘I’m going to win Wimbledon.’ It’s a fantasy. And within a fantasy, there’s always a feeling of resistance. You might believe you can do it, but you don’t know you can. So, there’s a huge difference.”

Steve Vai - Little Pretty (Official Visualizer)

This is the kind of stuff that Vai has put out there in his Under It All YouTube series, which includes about 14 or so hours of esoteric content that sometimes veers into self-help territory. But getting the scoop direct from the maestro himself feels even more enlightening when I realize what he’s saying isn’t just a positive-mental-attitude/self-realization fest. It’s the foundational core of Vai’s ethos, going back to his earliest work.

Even casual fans know the story of how young Steve Vai so impressed Frank Zappa with his transcription of the exceedingly complicated rhythmic brainteaser “The Black Page” that Zappa hired him. It goes without saying that the rhythmic and conceptual chops necessary for handling a work like “The Black Page”—or, really, most of Zappa’s catalog—takes a rare kind of brain. But the stars had to align to help the young upstart realize his destiny.

Everybody is inspired within themselves with unique ideas that are perfectly suited for their unique creativity in the world.

While he was a fresh-faced Berklee student, Vai met keyboardist/violinist Eddie Jobson—a former Zappa side musician—at a concert by Jobson’s band, U.K. “He started to explain to me what polyrhythms were and how Frank would write polyrhythms over whole bar lines,” he remembers. “I could immediately envision what a tuplet was, what a nested tuplet was—it all just made sense with regard to the timing of a bar or whatever you place that tuplet over. I was placing tuplets over beats that included tuplet timing in them.” This crucial info helped set Vai on his course. “I had an epiphany and then that just launched an intellectual forensic study of the division of time in musical notation.” Inspired, Vai took on the monumental challenge of transcribing Zappa’s work, and the rest is history.

Nowadays, at 61, Vai has fine-tuned his sixth sense for the whims of the universe and is maintaining an uncanny level of creativity. His latest album, the astounding Inviolate, is a straightforward—inasmuch as that’s a thing for Vai—barnburner, and it’s just the tip of the metaphorical iceberg. But as straightforward as Inviolate may be, the path leading to its creation was a winding one. Vai simply followed the cues that presented themselves.

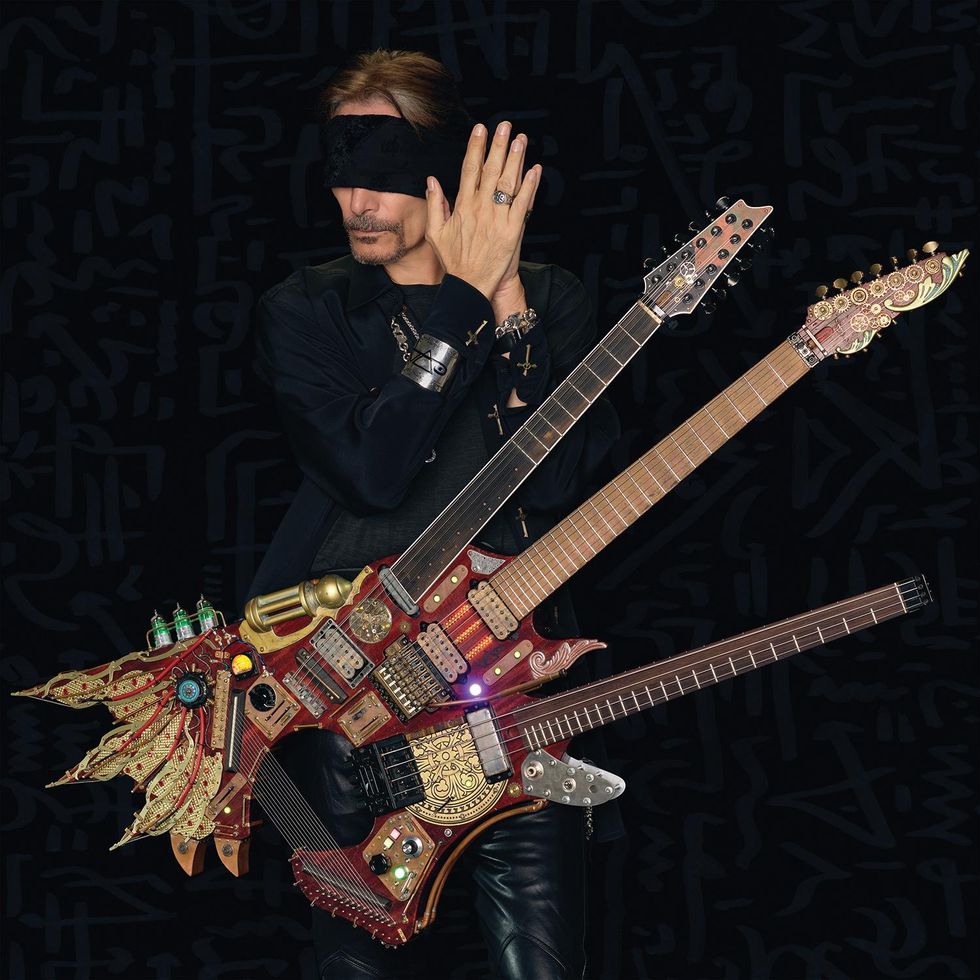

Vai poses with the gargantuan steampunk-inspired Hydra on the cover of Inviolate. It’s a heavy instrument that requires a waist strap. Still, he says, “it gets to your legs after a while” and “throws off your equilibrium completely.” Good thing it looks and sounds so cool!

In early 2020, he decided it was time to make the acoustic record he says “was one of those fantasy projects that I had written down through the years.” With “tons of material” to draw upon and a Paul Reed Smith Angelus acoustic, Vai posted a video of himself playing his song “The Moon and I,” his debut as a solo acoustic singer/songwriter. It’s a revealing performance in which he patiently builds tension in the strum-heavy intro and makes way for the sparse verse. His voice sounds strong, but slightly rough around the edges as he adds a little grit near the end of the song, exposing a different side of the virtuosic performer we’ve become accustomed to hearing play with only the most exacting precision.

Bolstered by the warm response the video received, Vai got to work recording 15 acoustic songs, all, he says, chock full of “beautiful, lush vocal melodies” and “rich chords.” But playing so much acoustic guitar posed some new physical challenges. “There’s one song where I have to fingerpick and I’m just not good at that,” he explains. “I was holding this obtuse kind of a chord way up high on the neck and there’s a lot of pressure on your thumb to hold your hands in place when your fingers are stretching. I just sat there meditating on this, holding the same chord while I was getting my fingerpicking together, and when I took my hand off, it felt like I sprained my thumb.” About a month later, his left thumb froze—a condition called trigger finger.

That wasn’t the only injury he sustained during the recording process. “There was one song that required strumming that was so fierce, so fast, that it would take me three weeks to build up to be able to get to the right tempo,” he says. “I worked on it, worked on it, worked on it, just about got it to where it needed to be—and I would have 14 guitar parts in the can and about three vocals. Unfortunately, that was as far as he’d get because his shoulder, which he’d injured a year prior, “just blew up.” He tore two tendons, which required surgery.

I had an epiphany and then that just launched an intellectual forensic study of the division of time in musical notation.

In December 2020, Vai underwent corrective surgery on his right shoulder, and surgery on his left hand followed in January 2021. Through his recovery, Vai wasn’t content to watch Netflix and chill. He simply couldn’t keep his hands off a guitar. So, with his right arm in a sling called a Knappsack—after Dr. Thomas Knapp, who performed his surgery and invented the device—and his left thumb still in a bandage, he got to work on a new one-handed guitar piece, “Knappsack.”

It was a simple idea. “I’m just gonna write a song with one hand,” he says, and insists “it wasn’t that hard. I just knew instinctively that I could get a tune out of just my left hand.” Donning his sling and bandage, Vai made a play-through video for his YouTube channel. It’s a dramatic look that does indeed contribute to the performance, but “Knappsack” retains the musically thrilling hallmarks of the maestro’s personal style, and its singable melody is bursting at the seams with expertly executed legato arpeggios and scale runs.

Once fully recovered, Vai was itching to get a tour booked. He decided to keep his acoustic project on ice and leaned into the idea of a new electric album. With “Knappsack” in the can, he created a series of musical challenges to overcome. He “set up parameters with the guitar that were somewhat out of my comfort zone” by using a hardtail Strat with a clean tone and playing without a pick for “Candlepower,” and he grabbed a Gretsch 6118 Anniversary on “Little Pretty,” which includes a difficult set of solo section chord changes. “It put up quite the fight but achieved what I was looking for.”

Steve Vai’s Gear

"Who else would do a three-neck guitar like that? I’m a total ham and I love it."

Photo by Michael Mesker

Guitars

- Bruno Urban custom 6-string

- Fender Stratocaster

- Gretsch G6118T-60 Vintage Select Edition ’60 Anniversary Hollowbody

- Ibanez Hydra

- Ibanez JEM “Bo”

- Ibanez JEM “Flo III”

- Ibanez JEM “Evo”

- Ibanez PIA

- Ibanez Universe 7-string

Strings & Picks

- Ernie Ball super Slinky Cobalt (.009–.042)

- Ibanez heavy

Amps

- Ampeg SVT Classic

- Carvin Legacy

- Lazy J 80

- 1980 Marshall with high-gain Jose Mod

- Marshall JCM2000

- Marshall JMP

- Paul Reed Smith Archon 50

- Synergy BMAN Preamp

- Synergy Vai Signature Preamp Module

- Victory V130

Effects

- Digitech Whammy

- Dunlop Cry Baby

- Fractal Audio FM3 Amp Modeler/FX Processor

- Ibanez Steve Vai Jemini Distortion

- MXR Phase 90

Despite his one-handed post-surgical musical opus, Vai says the biggest challenge on Inviolate can be heard on “Teeth of the Hydra,” where he debuts his newest creation, the steampunk-inspired Hydra, a three-neck beast that includes a 12-string neck that’s half fretless, a bass neck that has fretless E and A strings, a 7-string neck, harp strings, and a guitar synthesizer. Vai says the instrument, a five-year collaboration with Ibanez, “was a downloaded inspiration that came specifically for me because when it came I knew I could do it.”

When the Hydra was delivered, “I opened up the case and it was awesome and it was intimidating,” Vai says. “It had a big gnarly smile on its face. I propped it up in the studio and walked past it probably 20 or 30 times a day for a year, year-and-a-half, and every time I did it, it would go, ‘You know, you gotta play me. You gotta write that song.’ Finally, I carved out six weeks and I sat behind the Hydra and thought, ‘What was I thinking? What was wrong with me? What have I got myself into? People are gonna see me with the guitar and say, ‘He can get any guitar made he wants, but it’s all a gimmick.’’

But the Hydra was the product of his own brain, so Vai knew he could rise to the occasion. “I’m sitting there thinking ‘I’m in trouble,’” he admits. “And then that other voice came in and said, ‘You got this, you knew you had it all along, shut up and do it.’ And I sat down behind that thing and started motoring away slowly. I put a beat down and I started imagining.”

In late 2020 and early 2021, Vai had surgery on his right shoulder and left thumb. Injury is nothing new to the guitarist: “Through the 41 years of touring that I’ve done, you could probably name anything and I’ve had it. I’ve toured with slipped discs in my neck, right out of neck surgery. I’ve toured with slipped discs in my spine and had to get surgery … structurally I might be a little compromised because I grew up hunched over a guitar.”

Photo by Larry DiMarzio

The biggest challenge Vai created for himself wasn’t just to use the Hydra for a song, but to do so without looping or overdubbing. Although he learned he needed to record the harp strings separately because of how sensitive they are, Vai otherwise tracked “Teeth of the Hydra” in a linear fashion, performing one section at a time. “‘Candlepower’ and ‘Knappsack’ were probably two of the most challenging things I’ve recorded in my catalog, and they’re a walk in the park compared to the Hydra,” he says.

Any skeptics who might think that the Hydra is a gimmick should quickly be silenced by just how rippin’ “Teeth of the Hydra” is. Yeah, it’s a complete shred-fest, but it’s also tuneful and fun. That said, Vai is realistic and grounded about the concept of the song and of the instrument. “I’m an entertainer. It’s in my blood,” he says. “I love performing. Who else would do a three-neck guitar like that? I’m a total ham and I love it.”

When you’re engaged in those perfectly constructed inspirations that came to you for you, you’re in a state of enjoying what you’re doing right now, and life is only a series of right nows.

When we spoke, Inviolate was finished and Vai had an approaching tour (which has now been rescheduled). But he was planning to complete his acoustic record while travelling. In the summer, he’ll be heading to Holland to spend a month recording orchestral music with the Metropole Orkest. “I’m still keeping that side of my career going, because I love it,” he says. “I don’t expect my fans to go crazy for it, but some people will like it. At the end of the recording date with the orchestra, I should have about four albums in the can of new orchestral music. So, I’ll be balancing that with the acoustic record.”

And if that’s not dizzying enough, he just received a completed mix of an archival record from around 1990. “It’s my answer to the kind of music that I’d like to listen to when I’m out riding my motorcycle—when I was a teenager,” he says. “It’s kind of like ’80s rock with a biker edge. I found this singer, his name’s Gash, and the guy could sing like I never heard anybody. I wrote this stuff in a stream of consciousness and recorded it in about a week.”

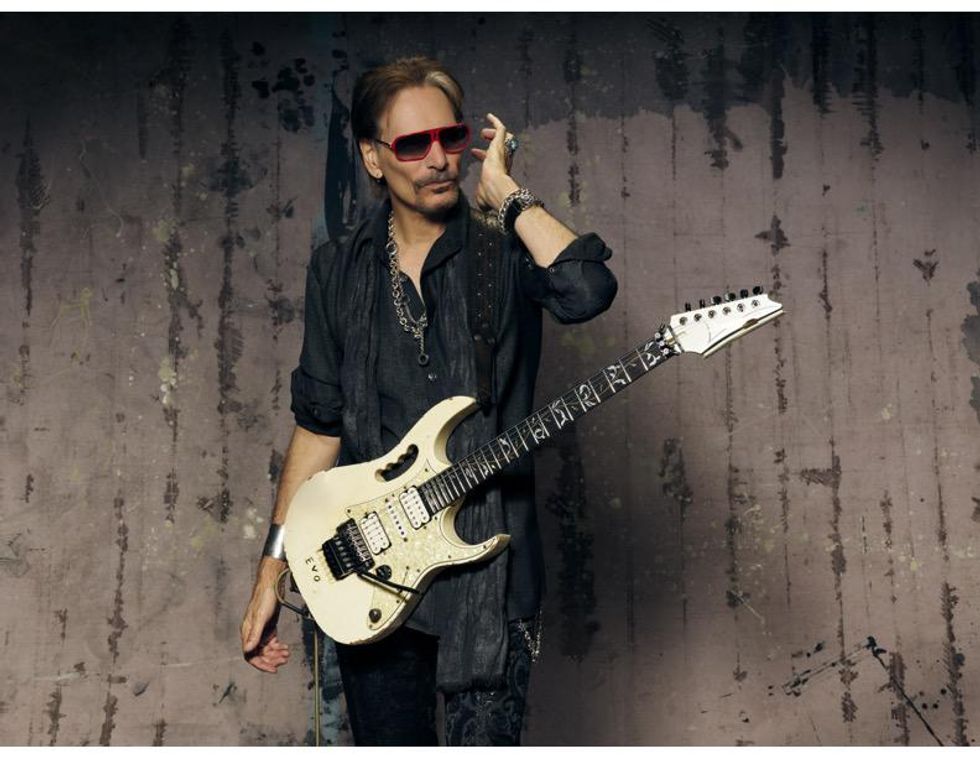

Vai with Evo, the Ibanez JEM he’s been playing since before he recorded 1993’s Sex and Religion.

Photo by Larry DiMarzio

As we get off the call, my head is spinning just thinking about how Vai is going to split his time between a full-on rock tour, producing an acoustic record, and recording hours of orchestral music. It’s mind-boggling on a technical and creative level—not to mention his time-management skills must be seriously on point. Plus, he’s maintained this high level of activity for so long, sustaining his drive, motivation, and quality of work.

When I inevitably find myself wondering “how does he do it,” I keep coming back to this one nugget of wisdom he shared: “When you’re engaged in those perfectly constructed inspirations that came to you for you, you’re in a state of enjoying what you’re doing right now, and life is only a series of right nows.” If that’s the case, Vai seems to be making the most out of every one of them.

Steve Vai - "Candle Power"

For his 60th birthday, Steve Vai challenged himself to record a track on a hardtail S-style guitar with a clean tone and no pick. He ended up inventing a multi-string bending technique he calls joint shifting, which he uses in this play-through video for “Candlepower” (from Inviolate) to thrilling—and funky—effect.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.