“You know what’s happening in Mali, right?” Vieux Farka Touré casually asked a sweaty crowd at Philadelphia’s World Café Live this spring. It was a brief aside in a propulsive set that had little downtime. Rather than elaborate, he quickly led his trio into the next pulsating song. It was a short interruption tossed out in the same low-key style as his other more routine between-song banter, but an indicator that Touré wasn’t there just to entertain. He was on a mission.

About a month later, the guitarist is sitting on the veranda of his Bamako, Mali, home, and talking via Zoom. “If you’re a musician, you’re an ambassador,” he says, explaining his philosophy. “You’re working for your country. People have to know exactly what’s happened here.”

Vieux Farka Touré et Khruangbin - Tongo Barra (Visualizer)

In that last remark, he could be talking generally, outlining a career-long ambition. He has continued to build awareness of Malian culture worldwide in the years since his father—the legendary Ali Farka Touré, who helped bridge traditional Malian music and American blues, and won two Grammys for his collaborations with Ry Cooder and Toumani Diabate—died and Vieux’s musical career began.

But in this case, he’s specifically referring to the turmoil Mali has faced in recent years. “Everything is very, very bad. Two days ago, they killed 132 civilians,” he explains, citing a recent attack by jihadist rebels. Since a 2012 coup, the country has fought to stem an Islamist insurgency and has been host to the UN’s deadliest peacekeeping mission.

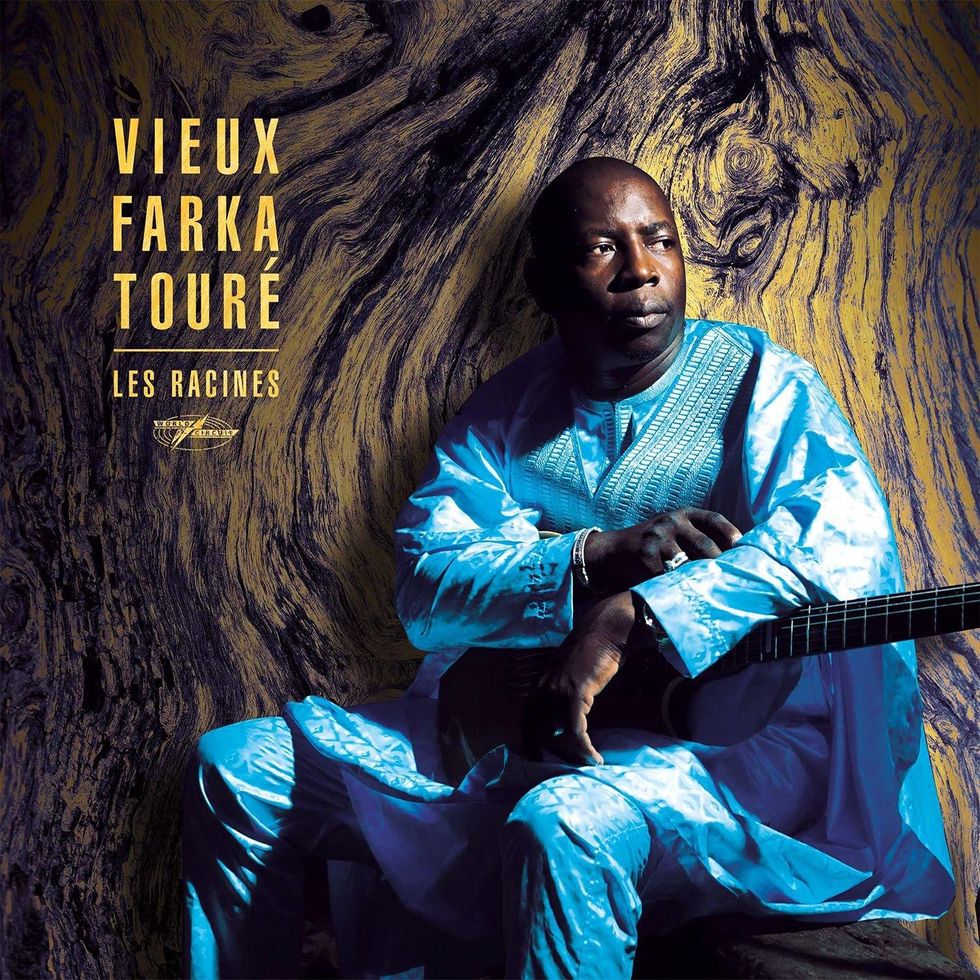

Touré sings about Malian affairs throughout this year’s Les Racines. “Real musicians want to do something,” he says. “Like in the World Café. It’s good to tell the people; they have to see what’s going on.” Across the album, he sings over beds of warm, crystalline fingerpicked guitar figures, mesmeric bass lines, and the percussion patterns that are the major contributor to its traditional sound. In the liner notes, Touré explains the meanings behind his lyrics, writing that the incendiary mid-tempo “Tinnondirene” “is a call for community dialogue, that is to say to set up a formal framework of consultation in order to play a role in the process of national reconciliation in Mali.” On the upbeat album closer, “Ndjehene Direne,” he sings that “insecurity reigns” and pleads, “If we love our country, let us be the force to overcome the misfortune that divides us, because there is strength in unity.”

“If you have a father like Ali Farka.… He’s the biggest traditional musician in Mali, so no way you’re gonna be on the same level as him.” —Vieux Farka Touré

“My politics—it’s to use my music, to use my name, to use my picture to make it better,” Touré says. “I love kids, so to make it better for kids, it’s very important. This is why I tell you the lyrics.”

The guitarist is passionate about his musical heritage—he’s also just released a tribute album to his father, called Ali—and the impact it has on Malian culture. Les Racines translates from French as “the roots,” and Touré writes that the slow instrumental title track represents his “full circle return, after years of personal exploration and work in all types of music, to the importance of traditional music and the realization that all music and modernity has its origins in its roots.”

“In Mali, every day the music is getting bad,” he asserts, and adds that the sound of traditional Malian instrumentation is being lost in contemporary music. To that end, he’s set up Studio Ali Farka Touré. “My father always would like to build a studio to help the people,” he explains, “so, I tried to do what my father would like to do. I built the studio.” Touré now uses the studio as a home base for his own projects—including Les Racines—and to produce records for other artists, and it’s also available for rent as a commercial studio. The only rule? They must use traditional instruments. “You wanna use the traditional instruments? The studio’s for you, man. Even the rappers who are coming, they have to use the traditional stuff.”

Fresh Sound

Touré’s guitar playing draws obvious comparisons to his father’s iconic desert-blues sound, in which it’s deeply rooted, but he plays with his own style. Starting in 2001, the young guitarist studied with his late father until his passing in 2006, and he learned to use the traditional right-hand technique in which he plays bass accompaniment with his thumb and uses his fingers for melody and lead. On his 2007 self-titled debut, Touré emerged seemingly fully formed with a musical voice of his own. “I don’t know how I got there. I can’t explain,” he says. In the intervening 15 years, Touré’s playing has only gotten more detailed and personal. “My father told me this all the time, ‘Don’t follow me, don’t follow anyone, you have to be you. The music is coming from here [gestures to heart], so you play just what you feel.’”

Vieux Farka Touré’s Gear

Vieux Farka Touré leads his trio with bassist Marshall Henry and percussionist Adama Kone in Bratislava earlier this year.

Photo by Barbora Solarova

Guitars

- Godin LGXSA

- Godin A6 Ultra

Strings

- D’Addario .010-.046 XL Nickel Wound

At the World Café, as his band—which included bassist and manager Marshall Henry and percussionist Adama Kone—wrapped up the first leg of their U.S. tour, they delivered a raucous, jubilant set that bridged his traditional roots and electric wizardry. They opened with a pair of ballads featuring the acoustic sound of Touré’s Godin LGXSA and Kone playing calabash. By the third song, Kone moved to the drum kit, and Touré queued up a bright electric tone on his Boss ME-80.

Ali’s Legacy

Touré knows that his father’s formidable reputation casts a large shadow, and its driven him to make his music stand apart. “All the people I see following what their father was doing,” he explains, “they didn’t do anything, they didn’t go anywhere, they stayed there. I have to do my own stuff.”

But the guitarist is ready to take on his father’s music along with his roots. On Les Racines, he recorded some parts with Ali Farka’s solidbody Seiwa Powersonic, and he’s dedicated “L’Âme” to his memory. But while Les Racines is a vehicle for Touré to use his creative voice as a songwriter and guitarist to work within traditional music, he also wants to modernize his father’s work.

Les Racines, which translates to “the roots,” was recorded in Touré’s newly built Studio Ali Farka Touré in Mali, where he promotes the use of traditional instrumentation in all genres.

“If you have a father like Ali Farka.… He’s the biggest traditional musician in Mali, so no way you’re gonna be on the same level as him,” he explains. “So, I say, ‘Make your own music, make your own place, make your own type, and, after, you come back.’” To do so, he’s tapped the bewigged psychedelic Texas-based trio Khruangbin to collaborate on the transcendent, reverb-soaked Ali.

The guitarist first approached Khruangbin about working together in 2017. They hit it off after an initial meeting the next year, and the quartet headed to Houston’s Terminal C studio in 2019 for five days of jams. Armed with selections from Ali’s catalog, Touré took his regular approach to arrangements, creating the grooves in his head and teaching the band.

“Vieux knew what he wanted to do when we went in,” explains Khruangbin’s guitarist, Mark Speer. “No one told us what we were going to be playing. We just showed up and sat down. He basically was like, ‘This is how the song goes.’ It was very organic. It was very loose and free.”

Fierce foursome: On Ali, Touré teamed up with Khruangbin to interpret a set of music by his father, the legendary Ali Farka Touré.

The quartet kept a leisurely schedule, working from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. each day, followed by family-style traditional Malian dinners of fish and rice. While the initial sessions proceeded in more of a traditional jam style, as Speer and bassist Laura Lee detail, the recordings were left to Khruangbin to shape and bring into their own sound world.

Because the sessions took place during the same period as the band’s Mordechai and Texas Moon albums—the latter a collaboration with singer/songwriter Leon Bridges—it wasn’t until 2021 that they revisited the recordings. This worked in Khruangbin’s favor. “I like parts and I like to sit and craft parts, and I typically like to do that alone,” Lee points out. “Rarely do things get to marinate for two years, so there was a real freshness when we came back to it.”

Working with Touré forced Speer to consider his own instrumental role. “Straight up, I was like, ‘I’m not really sure what I should be doing.’ The dude can play the accompaniment and the melody and he’s singing at the same time, and it sounds great. So, I was like, ‘Do I even need to play guitar? And if I’m going to play guitar, what am I going to play?‘” Speer's resultant guitar parts are a testament to his role as an effective big-picture creative thinker, and his stark accompaniments to Touré’s sinewy lines float over Lee and drummer Donald “DJ” Johnson, Jr.’s deep-groove rhythms, giving the record a widescreen-sunset feel—an ideal framework for the elder guitarist’s tunes.

When Touré approached Khruangbin about working on a collaborative project back in 2017, Laura Lee, the band’s bassist, says the guitarist received “an instant yes from our camp.” The result is the just-released Ali..

Throughout Ali, Touré sounds at home with Khruangbin. Whether on the desert-blues rager “Mahine Me,” the ethereal “Savanne,” or the funky and propulsive “Tongo Barra,” he boldly takes his father’s music to fresh sonic spaces, putting the mark of his singular creative vision on the material.

The Khruangbin-Touré team-up is no doubt a mutually beneficial one. The trio have carefully sculpted a musical persona steeped in global flavors, and Touré’s firm roots and deep authenticity certainly lends credence to their approach. So on Ali, Khruangbin are no longer particularly adept re-interpreters of international sounds, they are originators.

“The dude can play the accompaniment and the melody and he’s singing at the same time, and it sounds great.” —Mark Speers

If the music world is a fair place—though it’s famously not—Ali and Touré’s association with Khruangbin will raise the guitarist’s profile among Western audiences who might not know about Les Racines and his earlier work, and will hopefully take him to a place beyond nicknames like “Hendrix of the Sahara”—which gets lazily thrown at African guitarists from Mdou Moctar to Farees to Touré, who may have been the first to earn the moniker.In the big picture, it’s probably more important that both Ali and Les Racines allow Touré to further his musical mission. Each record marks a conversation between this master player, his rich musical tradition and heritage, and the modern world. They explore different moods, with distinct parameters. While Les Racines tells people “how they have to be,” Ali is a celebration, and both are necessary parts of Touré’s music. Taken together, they make a major statement and mark a decisive step in Touré’s work as one of Mali’s musical ambassadors.

YouTube It

Vieux Farka Touré and percussionist Adama Kone run through a trio of tunes at the 2022 New York Guitar Festival. Without a bassist, the guitarist’s right-thumb accompaniment is easy to hear and feel, and he plays fluid call and response between his powerful voice and his rapid, percussive fingerpicked leads.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.