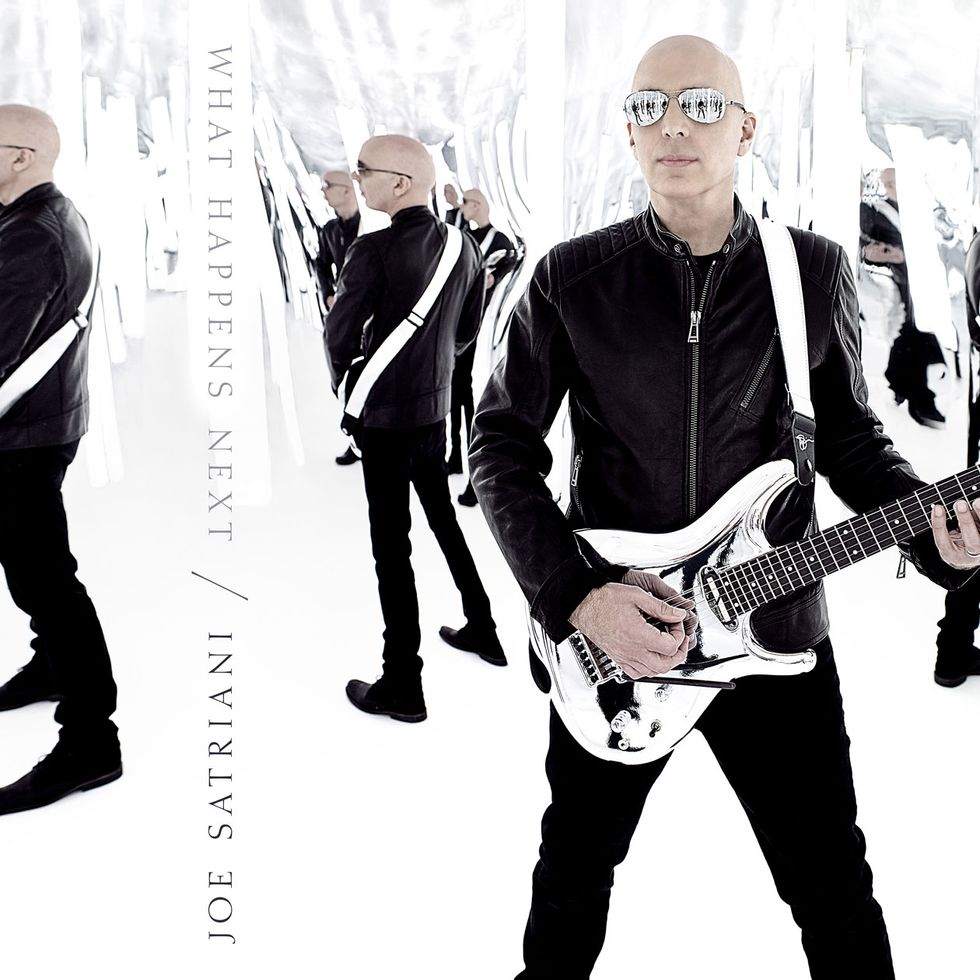

The title of Joe Satriani’s new album is What Happens Next. That’s a question we all ask ourselves from time to time, but in Satriani’s case, it’s an answer. After 31 years as a solo recording artist; collaborations with Mick Jagger, Steve Vai, Ian Gillan, and Alice Cooper; his ongoing membership in the rock supergroup Chickenfoot: his curation of the scalding touring concert series G3; and a commercial yardstick that includes 15 Grammy nominations and more than 10-million albums sold, Satriani’s last two projects were a kind of reckoning.

In the making of his previous album, 2015’s Shockwave Supernova, and the filming of a documentary, Beyond the Supernova, which was filmed by his son ZZ during the album’s tour, he wrestled with his largely secret career-long stage fright. It wasn’t debilitating, but he felt that it kept him from being, as he puts it, “just Joe from Long Island, playing in front of a bunch of people.”

There is, of course, also the notion of what does an artist as accomplished as Satriani—who has the ability to shred, soar, transport, and sometimes tear open his soul with a plectrum, six strings, and a signature model guitar—do for his next magic trick? The answer he found in What Happens Next was, essentially, writing and performing music that’s rooted in the sounds that excited Joe from Long Island. His new album goes back to a power-trio foundation, with fellow Chickenfooter and Red Hot Chili Peppers drummer Chad Smith and the ubiquitous bass powerhouse Glenn Hughes. And its baseline is the classic rock and soul that first fired the imagination of the kid from Carle Place. Built on a live-performance backbone, the album embraces the chicken-shack rhythms and heady funk perfected by Jimi Hendrix and Curtis Mayfield in tunes like “Forever and Ever” and “Headrush,” and stokes its own primal energy in “Cherry Blossoms.” The reckless boogie of bands like Humble Pie and Mountain reverberates in the opener “Energy.” And, being a Joe Satriani recording, the album is ceaselessly melodic and textured, reaching high planes of tone and compositional invention without sacrificing all three players’ devotion to rocking out.

When we talked with Satriani, he was about to begin the six weeks of practice he uses to prepare for each tour. He spoke about his sources of inspiration, his battle with butterflies and the positive side of self-consciousness, painting and drawing, his roots, the freedom that comes with playing instrumental music, the joy of reverb, and, of course, his guitars and the making of What Happens Next.

What makes you happy?

Family relationships are at the core, and I would imagine that’s the same for everybody. I hate to admit it, but artists need support. Musicians need managers and lawyers and accountants and techs around them, but the creative part, the soulful part, really needs a loving, supportive family structure, and also one that is intellectually and artistically challenging. Not for a second do I take for granted how much support, love, and help I get from everybody that’s part of my inner circle.

During points of incredible stress, creativity also comes through and does something. You go through a life tragedy and you write a piece of music that represents it. But besides a couple of songs that came out of some horrible moments, most of my best work came from when I was free to forget about all that stuff and just work on creativity.

If we move that microscope even closer: Imagine you’re at a studio session, and you’re not happy with your guitar sound, and the producer is telling you to hurry up—versus the engineer or the producer telling everyone to leave the room so the artist can play around for a few hours until he finds the sound that makes him happy. So, when you’re in that situation where, as guitar players are, you’re just endlessly searching for that right tone, that right effect, or the right guitar, it’s great when the people around you give you that space and time to find that tone, before forcing you to start performing.

The take-away is: Don’t even think about it. Just concentrate on the music, being prepared, physically and emotionally, for the project, and then that part of you that’s the professional musician takes over. That’s the part that deals with scheduling, and the wrong gear, and having to change studios, or personal issues. Those things are always going to happen and you’ll never work out a formula for it.

While listening to your music, I’m often visualizing things or am taken to a different place. That makes me wonder what other art form has the most profound effect on you?

Definitely visual art. I have three sisters, but the two oldest, the twins, are professional artists, so for as long as I can remember, when I would walk into their bedroom as a little kid, they were always drawing and painting, and I grew up with their art around the house. It became part of what I thought people did. I’m nowhere near as good as they are. As a matter of fact, I’m pretty terrible, but I really do love to draw.

TIDBIT: Satriani reunited with his frequent collaborator, producer/engineer/mixer Mike Fraser, to make What Happens Next. Fraser has also mixed every AC/DC album since 1990's The Razors Edge.

And this past 12 months, I embarked on a campaign to teach myself how to use paint and canvas, which is something I never did. I always worked with pens and then computer manipulation. It’s been very transporting. I’ll put on a record and I’ll get out a fresh canvas, and I’m in another world for hours. Most of the stuff turns out terrible [laughs], so it’s definitely not a professional venture. I’m doing it just because I love doing it, and when my fingers get tired from playing guitar, it’s a great way to stay creative and give the fingers a break.

And that channels into your music?

I think everything does. I continually get inspired by really big things—events in the world, in my world, too—and little things that don’t make any sense, like you wake up too early one morning and you look out the window and see the light of the dawn hitting a tree in your backyard a certain way, and suddenly you’ve got an impression of something unique. You’re fascinated by life itself, and suddenly there’s a musical idea. I can never be a visual artist. I can’t really get perspective together. I struggle with three-dimensional representation. But what I enjoy doing in two dimensions is capturing certain feelings. Once I got comfortable with what I couldn’t do, and what I could do, then it sort of set me free. So, I can spend time drawing and then look at it and say, “Now, musically what’s going on with this character that I’ve just drawn?”

Let’s talk about Little Kids Rock, the organization you support that promotes music education in schools.

I got involved through Jon Luini of Chime Interactive [a digital services and multi-media production company]. He’s a bass player and very community-minded, so he uses the internet to bring people together for different causes. He wanted to find a way to get instruments into the hands of kids at schools with struggling or no music programs. I loved the idea, and over the years—when I’ve had the time—I’ve visited schools to help some kids get guitars in their hands and get materials to schools that need music programming back in their daily lives. When I went to public high school—I started in the late ’60s—I had orchestra, band, chorus, music theory, advanced music theory … in Carle Place, Long Island! The whole town is, like, two square miles. I got an education in music from a Juilliard graduate who taught music theory at this public high school. And they also had a good football team and a wrestling team and everything else.

A few years ago, I visited a high school and a middle school here in San Francisco with Little Kids Rock. They only had one music program, and the only reason it existed, I think, was because Little Kids Rock came in and decided to lay down all these guitars and sheet music and to bring materials to make up for the shortfall in the budget. There was no art program in the school. I couldn’t believe it. How are you gonna turn these beautiful young kids into fascinating adults for our society if you don’t educate them? It’s just insane.

This is a shot from Satriani’s first gig, at the Carle Place, Long Island, high school gym. “I was so nervous, but I was having so much fun,” he says. “I did not face the audience. I just faced the drummer.” Courtesy of Joe Satriani

In Beyond the Supernova, the documentary your son ZZ made about you on the Shockwave Supernova tour, and in the making of What Happens Next, you’ve talked about having long-term stage fright, which I would never have imagined, given the boldness of your performances.

Well,we’re talking about just being shy [laughs], but I guess the difference is that I know so many other performers in the public eye who are not shy. The transition from talking to you backstage to walking onstage and doing a fantastic concert is a smooth one, and I’ve always marveled at that. Whereas if you told me today, “Hey, Joe, you’re gonna be playing on the Jimmy Fallon show next week.” I would immediately start getting nervous, because there’s something inside of me that says: “Whatever you do, don’t do that! Too many people looking at you.”

Sometimes I think it has to do with my earliest experiences as a kid, being exposed to strangers looking at me. And for a reason that makes no sense in my adult life, I’ve carried that over as if it’s still happening. It’s like the first time you eat a food that doesn’t agree with you and you never forget it. Or you have a bad experience with tequila and then never drink tequila for the rest of your life. I seem to remember having a really bad experience my first day of kindergarten. Everything was going great, and in the classroom there was a wall that was pretty much all windows, and it faced the outside grounds, where kids would play. Anyway, we’re in that classroom, the blinds are down, and at some point the teacher raises the blinds, and there were all the parents sitting on folding chairs, staring into the classroom [laughs]. I remember feeling total dread. I believe my mother was one of the parents out there. So why would I feel bad about it? I have no idea. I think it was being observed, like a fish in a tank. The class ended for me—I started crying.

I recently dug out a photo for my son, who is completing the documentary, and it’s a picture of me playing at the Carle Place High School gym, my very first gig. I told him, “I was so nervous, but I was having so much fun. I did not face the audience. I just faced the drummer.” And sure enough, it was the only photo from that whole era, and that was it: me, with my back to the audience, looking at the drummer while everyone else in the band is facing forwards. That same feeling carried over into my career.

But being a performer has also probably helped open you up more as a person.

One thing you notice right away, when you start performing, is that there are wonderful things to be gained by opening up and being one with an audience, no matter how small.

and every measure.

You’re playing for your family in the living room or your friends at a basement party, then at a high school dance, or battle of the bands at a local club…. And before you know it, you’re on stages around the world. You learn that there’s this big, great thing that happens to you, to your soul, by opening up. But your basic nature, I think, is always there. And to some degree, it’s a good, protective mechanism because in a professional musician’s case, it’s that thing that says, “Maybe I should check my tuning, maybe I should check my gear, maybe I should replace the battery in that pedal, let me check the cables, do I have a backup?” Because if you’re too relaxed and cavalier, you may walk in thinking you can do anything. Then you realize you’ve forgotten some of the basic things. Like, “Did I bring a backup battery for my wah-wah pedal?” Or, “Did I bring a second set of strings?” These things you learn, painfully, in your first couple of gigs.

It’s a kind of positive self-consciousness.

It is. And it’s not apprehension, and this is where I need to do some explaining, because even though I’ve said that I have this feeling that I shouldn’t take that step out onstage, that’s not really what it is. I’m nervous and I’m shy, but I’m still happy that I’ve got this anticipation. And the butterflies in my stomach are the precursor to the fun I’m about to have, and that’s what always gets me back onstage. At the end of the night, I go, “Man, that was the greatest thing ever. That was the best. And why was I fretting over it?” No pun intended, but why was I nervous, you know?

Let’s dive into What Happens Next. On “Cherry Blossoms,” the drumming is extraordinary. It’s got a beautiful primal, tribal thing, and the tone has a marvelous patina. Since you initially wanted to be a drummer, how does Chad Smith’s playing speak to you?

I think Chad’s the drummer we all want to be. He replaces those great rock drummers that I grew up listening to: Keith Moon, John Bonham, and Mitch Mitchell. They created some of the greatest rhythms and textures without ever reminding me of technicality. I would say the same thing for Ringo and Charlie Watts. They’re never methodical or didactic. It just sounds like a human being banging on something in the most perfect way.

Guitars

Ibanez JSM2410 MCO

Ibanez JSM ART (one black, one white)

Amps

Marshall JVM410HJS

Marshall 1960B cabs with 75W speakers (2)

Effects

Fractal Axe-Fx II

Vox Joe Satriani Big Bad Wah

DigiTech Whammy

Fulltone Octafuzz

MXR EVH Flanger

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL110 (.010–.046)

D’Addario signature pick, celluloid, extra-heavy

Guitar players have noise—we have melody and harmony and electric texture, but the drummer … it’s rhythm and texture. That sense of rhythm sometimes seems to be sacrificed when people dive into a kind of technical, intellectual way of looking at drumming. But Chad’s personality and humanity comes through on the drums. His excitement about making music at that very moment is always present in everything that he hits. It’s so remarkable. It makes the experience of playing with him so exciting, because you have to hang on every note he plays. It’s not like he starts playing and you go, okay, he’s gonna play that for about a minute so I can just not pay attention to him [laughter]. With Chad, every split second you’re like, “Wow, listen to that! I want to get in on that!”

For “Cherry Blossoms,” Chad was very keen on making sure the drama that was on the demo continued onto the master take. He has a very keen sense of the cinematic drama that an instrumental rock song can really achieve. He totally understands that, because we don’t have lyrics, we have to be very specific with every single song, with the way that we play. It can’t be like a punk band where the band plays every song the same, since the lyrics tell you what the song’s about. An instrumental piece of music has the potential to really tell a story in a deeper way than a set of lyrics, because we’re giving the audience a chance to apply their own story, their own emotion, to each and every measure of the music.

What’s your strategy for demos?

I bring Pro Tools sessions into the studio and have a good sketch—especially in the case of this particular album, where I knew I had to jump in just two weeks after finishing the tour and meet these guys in a different city. I only had Chad and Glenn for about nine to 10 days. So, I had to present them with a clear vision of what we had to accomplish.

We’d come in in the morning and push play and listen to a track, and I’d say, “This is how it should proceed. Pay no attention to the horrible mix of my demo [laughs].” Because sometimes what I like to do with my demos is leave first impressions or scratchy bits because they remind me of some interesting idea that I had, but I hadn’t worked out the actual technique of how to get it done. And I do this because I want my producers to listen to what I was trying to achieve in the innocence of the moment. I throw it to them, like “Can I achieve that? How does that get done?” And all the guys I’ve worked with—primarily Mike Fraser and John Cuniberti—have been amazing at listening to some of my weirdest ideas and figuring out a way to get them done in the studio. It might seem simple when you’re listening to it, but it takes a lot of work and finesse on the part of each musician, who summoned unique performances.

Like I said before, if no one’s singing, then everything you play has to be very specific for the song. I always tell players, “This is not a shred record where the band plays in general and then the guy just shows how good he is on top, you know?” [Laughs.] Every song has a unique melody and a story that we’re telling, so let’s make believe it is a lyric record. With a song about chicken and waffles, you’d be playing a different drum kit, or you’d reach for a different bass guitar, than if it was a song about cherry blossoms, you know? I don’t know why I said chicken and waffles. I must be hungry!

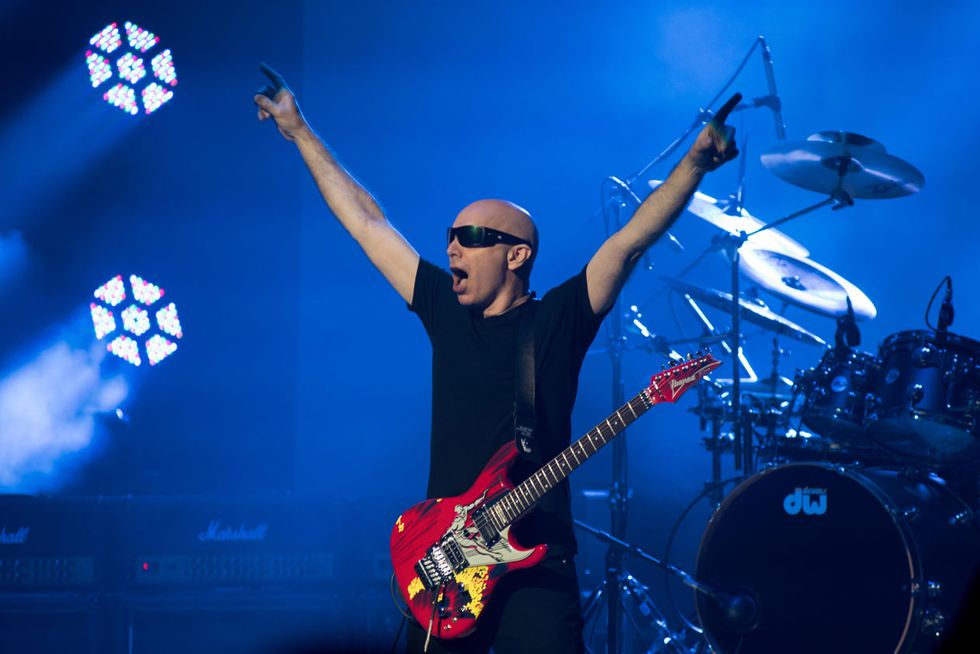

At this Atlanta Symphony Hall concert from March 2016, Satriani plays his black Ibanez JSM ART,

which he custom handpainted. Photo by Drew Stawin

Well, I’m in Nashville, so that resonates with me. When I hear your records, I think about them as a liberation from language. Language can have limitations or get unintended reactions from people because there are certain words that frame their own experiences. With a purely musical statement, you don’t have those limitations. You can transcend language.

I agree. A perfect example is pop music. Pop music generates a lot of money, and because of that, each new piece that comes out benefits from them spending a lot of money on production, getting the best people to be part of it. So, when a new million-dollar piece of pop music comes out, it’s extremely shiny, they’ve worked on it forever, and there’s been, like, 12 producers. You hear a really cool groove, you hear sounds you never heard before, and then, for me, you get let down when the person starts singing, because it’s some sort of trendy message that the artist feels they have to talk about. And you’re like, “Well, I don’t care about that!” You just wanted to enjoy the groove, and you loved the texture, and then suddenly you have to deal with these lyrics, you know?

That’s sad. There were periods of music, if you go back 50, 60, 70 years, where pop seemed to deliver messages that you could live with. When I was making records with Chickenfoot, it was a thing that we all, as a band, wanted to somehow get ahold of. Because Chickenfoot was our way of celebrating our roots. We were playing new music, but we were celebrating our roots growing up as kids learning how to play during what turned out to be the classic-rock era.

We wanted to make feel-good music, but there were things that Sam felt he had to talk about. So, I think every band that’s got a singer and a lyricist has to come to grips with that. Are they gonna write a song where it’s all about, “I love you, let’s have a good time tonight,” or is it gonna be “Avenida Revolucion,” where Sammy is screaming about the injustice of life down at the border? You make that choice, and you plant your feet firmly on the ground.

My earliest memory listening to instrumental music was listening to my parents play jazz records, and my mother playing a lot of classical records, because she wanted to get it into our brains. And I always loved it. I really felt instrumental music, both classical and jazz, and so any time my earliest rock experiences would show me an instrumental, I would gravitate towards it. Like, when I got that first Hendrix record, I loved everything about Hendrix, but “Third Stone from the Sun” just totally blew my mind! It was so beautiful to me. So powerful.

Since you mention Jimi, I hear direct Hendrix references on What Happens Next. Especially in “Forever and Ever,” with those awesome chicken-shack R&B chords that Hendrix was so fantastic at playing. People think of Hendrix as being a super-progressive rock guy, which he was, but he was also one of the greatest traditional R&B guitar players.

I’m glad you point that out, because when I sent out the initial message to Chad and Glenn, I said, “This new record is going to be all about rock and soul. Everything’s in 4/4. It’s going to be very essential, and some of the songs are gonna be R&B-ish.” I knew from playing with Chad that he had that in generous quantities running through his veins. And I knew that from Glenn, obviously.

He has that wonderful blend of being a complete rock-bass player as well as being a really soulful singer. So, the songs “Righteous,” “Smooth Soul,” and “Forever and Ever” get that by way of Hendrix and a lot of Curtis Mayfield. From what I know from talking with Billy Cox, Hendrix played rhythm guitar 24/7. That’s what he tried to perfect. And he took that to another level, and now it’s a thing. You know what I mean? When you play that way, everyone goes, “Oh, that’s Hendrix.” [Laughs.] I think Curtis Mayfield was probably the godfather of it all, and Hendrix was right there picking up on it, and then running with it a lot farther.

Do you have a daily practice regimen, to keep yourself open?

I don’t, but there are three phases in the life of Joe and his guitar. I play every day, unless I’m forced not to—like if I’m on a 23-hour flight plan to do a gig. Or maybe I’ve done too much playing and I need to take three days off or something like that. But in general, I’m playing every day for at least an hour, and if I’m writing, sometimes I’m playing 8 to 9 hours a day. And it’s very specific. I might play one song over and over again, to try to figure it out. If it’s a particular song that’s got something difficult about it, I might play it on one guitar through one rig, 45 minutes on, 2 hours off, 45 minutes on, 2 hours off … just to become completely familiar with the technique, which maybe at the composing level is so fresh that it’s awkward. I create a routine where I get rid of all that awkwardness so I can feel comfortable enough to be expressive with it. Then I think the last phase would be, if I know I’m gonna be going on tour, I’ll play what I think our set is gonna be once or twice a day for the next six weeks. Every day, all I do is address which guitars I’m bringing, which pedals, which amps, and how I’m gonna play the songs from top to bottom. It seems excessive.

Not at all! I think it sounds wonderful. You can let the whole thing seep into your body.

Yeah. And I want to explore as many different ways of playing something that I can. That seems to really help me, because, I must say, with the advent of G3 back in ’96, I learned again firsthand that some players don’t have the same issues that I have about playing. Playing next to Steve Vai, Paul Gilbert, or John Petrucci is incredibly rewarding, but it’s also frightening. They have talents in areas that I don’t, and I marvel at that. So that’s where I learned to do this extensive preparation. Not because I’m gonna hit the stage and do exactly what I practiced. It’s quite the opposite. I’m preparing myself for variation. Even if it’s a song I know like crazy, like “Surfing with the Alien,” half the time I’ll play it without a wah-wah pedal, just so I’m not concentrating on the envelope of the wah-wah. And I’m thinking, “I’ve played this for 30 years, but maybe I could play this phrase over there, instead of over there.” And I will continually do that. I’ll play the melody on a different set of strings. I’ll play a different solo. I’ll see if I can still make the song work with variations of fingering, picking style. I’ll use a different thickness pick, maybe a guitar without a whammy bar—just change it up to see if I can gain new insights into what the song has to offer.

Why call the new album What Happens Next?

That’s what I’m asking myself: “What happens next?” And already I’m writing songs that will become the next album, but also what happens is that the previous record, Shockwave Supernova, had a light narrative about me and my alter ego battling it out. It was somewhat a recognition of what we talked about at the beginning of the interview—dealing with stage fright and the whole idea of a shy, retiring person having a job stepping in front of thousands of people every night. I used that as a device to shape Shockwave Supernova, but at the end of the album I wrote a song that killed off the character I become onstage. I say, “You’ve got to go away. This is the real me.” And through the course of the tour, I started to realize how true that was, and that I really did want to evolve somehow.

I guess, through my son’s prodding and continually interviewing me as he filmed, and drawing these feelings out of me, I realized I was really trying to get back to the point where me and that character were the same person. Over the years, I started to think of me as being able to turn on that character to do all the more outrageous things onstage, but at the beginning it was just Joe from Long Island playing his guitar in front of a bunch of people. And that was part of what I wanted to use as the energy for the new record. When I wrote down the title, I said, there shouldn’t be a question mark there because it’s not a question to the audience. It was a question to me, but now I’ve done it, so it should simply be a statement. It’s more like, this is what happens next—because the answers are the songs on the new record.

“Over the years, I started to think of me as being able to turn on that character to do all the more outrageous things onstage,” observes Satriani, shown here on the Shockwave Supernova tour with his Surfing with the Alien guitar.

Photo by Drew Stawin

Might that explain why this album feels more rooted?

Yes! Very much so. I think when I brought the idea of Shockwave Supernova to John Cuniberti, he realized that it was going to be a record where each song would be a production extravaganza. In other words, every song was so different, but he knew there was gonna be this narrative that would pull it all together and would give us the artistic license to introduce each song differently. The band was perfect, because those guys were very keen on listening to each song and playing as if they were different people.

When we loaded into the studio for What Happens Next, I had a completely different agenda. I’d written these songs for Chad, Glenn, and myself—very specifically. And Mike Fraser knew we were going to record as if we were a band playing in your backyard. That’s why I didn’t bring a fourth member into the tracking sessions. What we wound up with was guitar, bass, and drums that really held the attention throughout the whole album. And any other textures, we would make them sound like they were fairy dust, as opposed to being completely in your face. The only difference being maybe “Catbot,” but that’s me on the keyboard. I wrote that song on a keyboard and then overdubbed my guitar on top, copying my keyboard part, which was hard, because not one phrase is the same on the keyboard, and it was strange to have to try to memorize all that variation on the guitar.

I like the octave effect on the guitar on that one. It’s got a sense of humor.

That starts with a pretty standard plug-in that turns a guitar into a wah-wah pedal, but it gets into a plug-in called Rectify, which basically destroys the sound. But it was a little bit humorous. I was thinking that if you have an electronic cat, like they have in Japan, where people have dogs and cats that are actually little robots [laughter], what if it got out, and it’s roaming down the street at night with the other cats, and they’re all looking it at it like, “Wow, is that a real cat?” Of course, the catbot goes to talk and meow and it comes out all weird sounding!

What’s your philosophy about reverb and delay—transporting elements in music that you use beautifully?

They are transporting. Why is that? You wonder why did they start doing that to vocals in the mid ’50s? Were they trying to make you feel like that’s what a singer sounded like in a club? So they would send Elvis’ voice out to the old propane tank in the back [laughter]. They did funny things—empty out the men’s room and put a microphone in there and a little speaker and have that come back. At [San Francisco’s] Hyde Street Studios, where I recorded quite a few of my early records, we used the women’s bathroom quite a bit, on the second floor. It had a great sound. But it has an effect on our soul. It does something to our brains, when we hear an instrument or a voice with some kind of reverberation or echo or delay.… It helps us understand more about this thing that’s happening. Think about “Bohemian Rhapsody” and the way Queen used reverb and total lack of reverb.

I learned about reverb from John Cuniberti. We’d be in the studio, and he’d say, “I want to show you this thing called non-linear reverb,” and instantly it was like, “Well, we gotta use that!” And we got the drum sound for “Not of This Earth.” He would tell me about pre-delay and all the stuff that we could do with reverb, and I started to really love it. I thought, “This is as important as an essential pedal on a guitar player’s pedalboard. It transmits so much feeling that we have to take control of it.”

I remember hearing the playback for [1992’s] “Friends” at Ocean Way in Los Angeles. Andy Johns was producing and me and the Bissonette brothers were playing. Andy calls us in and says, “Listen to what I’ve got.” And he turned on the speakers, and it was the most glorious moment ever. We could not believe the three of us sounded like that! He had taken part of the drums, miked them, put them into a PA system, generated the PA into that huge room, and then put mics into the back of the room and compressed them. He did this thing with natural reverb that made us so happy that, for the next couple of weeks, we just slammed through that record because we were so excited. And basically, we were responding to the reverb.

You play your signature guitars and amps every night. Are they stock or modded?

Both. Half the stuff I’ve got is completely stock and the rest is in a prototype stage, leaning towards the next production idea. For instance, when I first started playing the MCR [Muscle Car Orange] alder JS2410, it was a prototype, and I knew it would take a year-and-a-half to hit the market. By the time it came out, I’d already started prototyping putting a Sustainiac in the neck position, and by the time that came to market, we’d already prototyped several different colors. And this will be the first year where that MCR comes out with a Sustainiac in all positions. I’m always taking the prototype that’s looking two years forward out on tour, to make sure that it’s roadworthy before I tell Ibanez to push the button and make one.

Which guitars do we hear on What Happens Next?

It was a small group: my MCO, my MCP [Muscle Car Purple], and my JS25ART. The three guitars I had on tour wound up being the main guitars. Every once in awhile we’d throw in, you know, maybe a custom shop Strat or a Flying V or a Les Paul to be a twin to a JS guitar if we thought we needed something. And amp-wise, it was my signature JVM [the Marshall JVM410HJS] doing most of the work, but I also had my old Peavey 5150, I had maybe 10 or 15 old Marshall heads. I’d use the ’71 50-watt for one song and the ’74 100-watt for one song, the ’66 Super PA for one song…. that kind of thing. The only two unusual amps that were new were the [100-watt] Mezzabarba MZero I used for maybe one song, and there was a KSR Orthos on one or two songs. It was a very small group of gear compared to other albums where I had, like, 15 guitars and 30 amplifiers. I wanted, basically, the sound of my guitar into a loud Marshall. Sometimes you use a different amp to sound like a Marshall. Very often it’s the part and the key and the way the rest of the band is playing.

A final digression: In the trailer for Beyond the Supernova, when the band comes offstage, you all raise a finger and say “One.” Is that a ritual?

The ritual is, we always say something completely silly. But that’s from “the one shall be the number,” from Monty Python and the Holy Grail. It’s from the Knights Who Say “Ni” … “We are the knights that say ‘one.’ Two shall not be the number. Three shall never be spoken of.” [Laughs.] So that’s what that’s all about. But there’s a different cheer every night.

In this trailer for his son ZZ’s documentary Beyond the Supernova, which premiered at California’s Mill Valley Film Festival in October 2017, Joe Satriani talks about his stage fright, touring, and the rush of live performance. And shares the sign of “one.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)