Leland Sklar is sitting in his hotel room in Denver, Colorado, watching Law & Order. It’s a creature comfort he indulges in frequently while on the road. “The one good thing about it is, any time day or night, anywhere I go, I can always find it,” he admits. Similarly, one could argue that Sklar’s bass playing is also a universal creature comfort. He’s played with so many artists and recorded so many hits it’s hard to go anywhere there’s music, day or night, without hearing him.

Whether it’s his groundbreaking session work with singer/songwriters like James Taylor, Jackson Browne, and Rita Coolidge in the ’70s, or his contributions to the slick, polished productions of pop icons Phil Collins, Reba McEntire, and Warren Zevon in the ’80s and ’90s, or his forays into the country canon via artists like Clint Black, Vince Gill, and Faith Hill, Sklar’s bass playing has literally dominated the airwaves for five decades. It’s hard to condense his track record, which includes more than 2,500 recordings, but a smattering of Sklar-supported songs one might hear on the radio during any given day includes “You’ve Got a Friend” by James Taylor, “I Am Woman” by Helen Reddy, “Running on Empty” by Jackson Browne, “It’s Raining Men” by the Weather Girls, and “Another Day in Paradise” by Phil Collins.

But it doesn’t stop there. Sklar isn’t simply a fixture in popular music. He also has an uncanny knack for effortlessly transcending genres. From his performance on Billy Cobhams’s seminal jazz-fusion album Spectrum in 1973 to sessions with Toto guitar phenom Steve Lukather over the past three decades to film soundtracks like Doctor Detroit (1983), The Prince of Egypt (1998), and Legally Blonde (2001), it becomes evident that Sklar’s playing is free of stylistic constraints. And if you thought his skill set was any less desirable outside the States, forget it. He seems to transcend cultures, too. He just finished cutting a 33-track album with French artists Eddy Mitchell and Johnny Hallyday (who passed away after the sessions), and has recorded and/or continues to record extensively with artists from around the globe, including Marta Sánchez (Spain), Garou (Canada), and Vasco Rossi (Italy).

“I really feel quite blessed to still be as busy as I am,” Sklar, who’s 70, confesses. “I still get completely jacked when the phone rings or an e-mail comes in. I just finished a Japanese hard-rock project with Mari Hamada and was in the studio for a few days with Judith Owen working on material for her next album. Everything is still vital and fun. That, to me, is the essence of the whole thing. I still love this as much as the first day I did it. I still have that giddiness when someone calls and asks me if I’m available to do something.”

Sklar recently came off a “fabulous run” with Phil Collins in the U.K., where he played in front of 70,000 people in Hyde Park and 45,000 people in Dublin. He’ll be back in the U.K. with Collins in November at the Royal Albert Hall in London. PG caught up with him over the summer in Denver, while on the road with singer/pianist Judith Owen in support of her 2016 release Somebody’s Child. It’s a record that epitomizes his playing style as he complements piano parts and enhances vocal melodies all while establishing killer, seemingly simple, grooves. He seemed delighted to take a break from Law & Order to talk about the foundation of his prolific career and playing style, the “Old Frankenstein” bass he’s used to cut those 2,500-plus recordings, and his predilection for playing whole notes.

How’s the Judith Owen tour going?

It’s great. She’s a unique artist to work with. Her style of writing really harkens back, for me, to my early days with James Taylor and Jackson Browne. She’s a beautiful writer from the standpoint of storytelling and is very succinct in the way she expresses her stories. They are incredibly relatable. She’s also a gifted pianist and singer. There’s a wide breadth of stylistic things and I never find it dull. It’s fun to get your teeth into musically. And the instrumentation we use on the tour is great because she’s playing piano, I’m playing bass, Pedro Segundo is playing percussion, Gabriella Swallow plays cello, and Lizzie Ball plays violin, so it’s a unique musical lineup that really complements each other well.

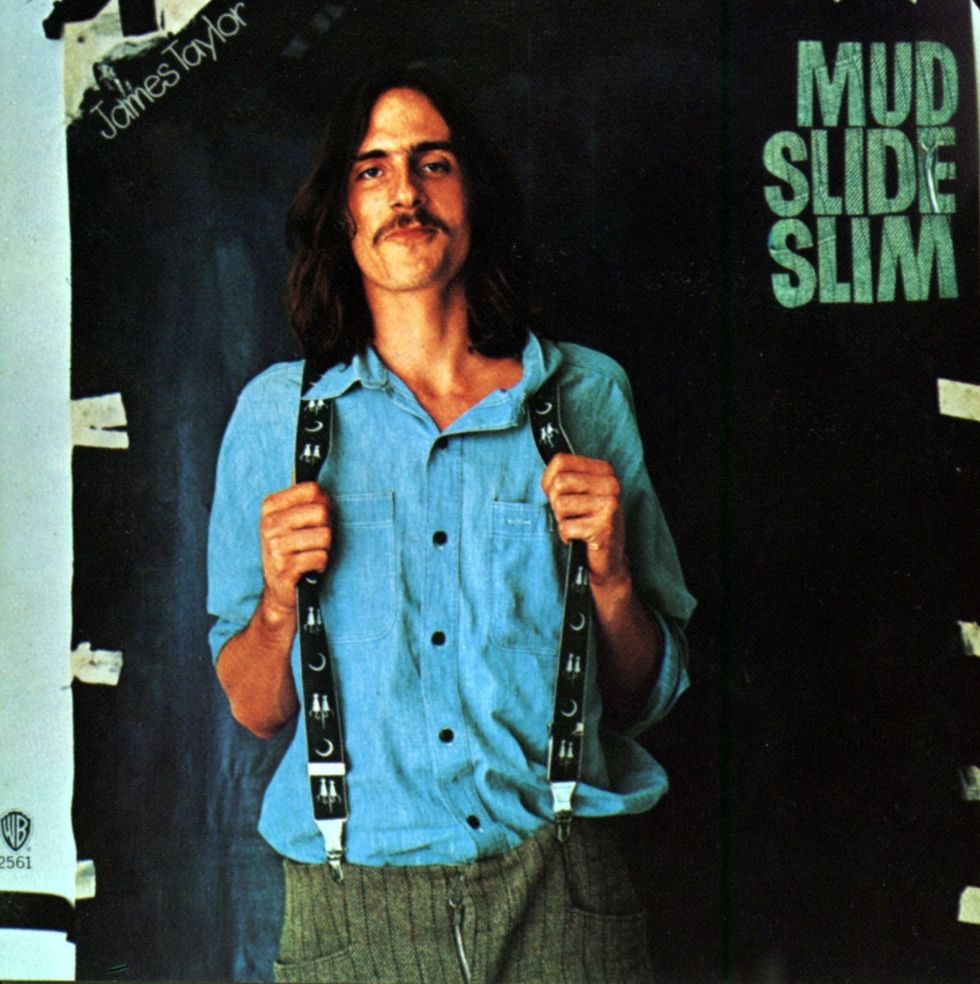

James Taylor’s manager insisted his studio bands’ names appeared on the back of Mudslide Slim and the Blue Horizon. “So, when this new movement came along of singer/songwriters, people could look at James’ record, which became the benchmark, and they would see our names,” says Sklar. “The next thing you know, I’m getting calls to do studio work.”

How did you develop your playing style?

Working with James Taylor really required a particular approach, musically. He’s probably one of the most underrated guitar players ever. He plays in such a comprehensive style—with his constant, moving thumb bass going through all his songs. It was really a challenge for me to sit there and think, “What the hell am I going to do? How do I justify being here when he’s already got it covered?” And so, I immersed myself and really tried to find ways of lyrically weaving things together.

Can you articulate how you weave things together?

In one moment, you’re aping them [singer/songwriters] and joining in with what they’re doing, but then you must be able to step away from it and find alternative patterns that keep the thing moving. I’ve always tried to justify my being there without becoming intrusive. I find it a great challenge to listen to a song and figure out, “What does this ultimately need? Or not need?”

Does it relate to the age-old “less is more” adage?

There’s no chops in playing a whole note. If that’s what it demands, then I’m quite happy. I remember doing a dissertation on a whole note once that lasted about five minutes, and these guys in the room, I think it was at the Bass Centre in L.A., asked, didn’t I find it boring to play simply on a song? And I said, “Absolutely not. Sometimes the simple ones are the absolute hardest to play.” It was an enlightening evening for all of us.

Did you have any formal education, musically?

I started as a classical pianist when I was 4. I studied until I was 12. I was the proverbial prodigy kid. When I was 7, I won an award from the Hollywood Bowl Society for outstanding young pianist in Los Angeles.

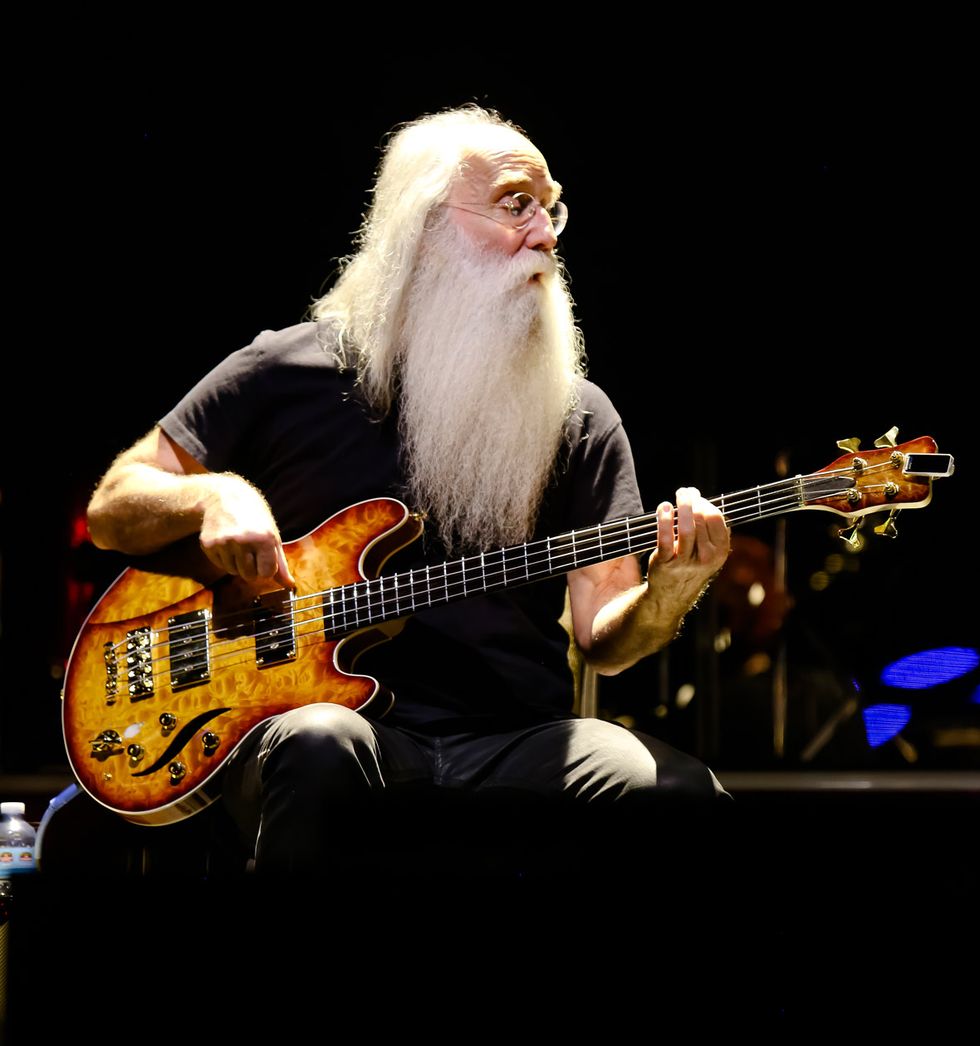

Lee Sklar began playing bass in junior high school. More than a half-century later, he is one of the instrument’s preeminent figures, with more than 2,500 recordings to his credit. Here, he plays one of his Warwick axes. Photo by Steve Kalinsky

What about on bass?

When I went to junior high school, I walked in there like a cocky little shit and said, “Your piano player is here.” The teacher, Ted Lynn, looked at me and said, “We’ve got 50 kids who play piano; we need a string bass player,” and he pulled an old blonde Kay upright out of the back room and handed it to me. I knew nothing about it, but I put that bass against me, plucked a note, felt the vibration run through and said, “sold!” He took me aside and gave me some rudimentary lessons on how to get around on the instrument. I just fell in love with it and the piano fell by the wayside completely. I was thrilled to find something new that let me sit in the background.

How did your recording career first take off?

The thing I was really blessed with was when we did James’ third album, Mud Slide Slim and the Blue Horizon, Peter Asher [Taylor’s manager] insisted that our names appear on the back of the record as the musicians—Russ Kunkel (drums), Danny Kortchmar (guitar), and Carole King was the piano player [along with keyboardist Craig Doerge, they all became independently known as the Section]. So, when this new movement came along of singer/songwriters, people could look at James’ record, which became the benchmark, and they would see our names. The next thing you know, I’m getting calls to do studio work.

Had you much recording experience at that point?

I’d done some demos, but I never recorded an album before. Suddenly, we were thrown into the fire of really having to craft sounds, understand what the studio scene was like, and understand how different that was from being in a live band. It really required some serious focus, but I fell in love with it. Once that started, we hit the ground running.

I guess you were kind of following in the footsteps of the Wrecking Crew.

Absolutely. It was the golden age of all this. So many artists were being signed and so much of it sat on our shoulders. Nobody was coming in with charts. They would come in and sit and play piano or guitar and have us create for them. Our contributions were really us, and not just as conduits to an arranger’s charts.

How do you avoid repetition in your playing?

For me, everything really feels fresh no matter what. I really fly by the seat of my pants and try to live in the moment each time. On tour, I never play the same song the same way twice. I always look for other nuances that come with the sound of the hall, the look or vibe of the audience, the placement of the band onstage. So many little things factor in that make you respond differently each time. So, I try to live in that given moment. When I was with James Taylor, I can’t tell you how many times I played “Fire and Rain,” but the thing that was foremost in my mind every time was, “I might’ve played this 5,000 times, but there’s somebody in the audience who is hearing it for the first time.” And that’s who you pay attention to and that’s how you respond.

How are you able to apply what you do to so many different genres so seamlessly?

I’ve been fortunate in that, whatever it is Ido, there seems to be a great common denominator. If I’m working on a reggae record, I can do the few things that create reggae in terms of drop beats and different things like that, but I don’t do them that much differently than I would if I was doing a Vince Gill record down in Nashville or if I was doing some pop record in L.A. The way I approach music seems to take on a general consensus of fitting into all these genres without having to rethink the way I play.

Basses

Old Frankenstein (4-string)

Warwick Star Bass II, fretted & fretless (4-string)

Warwick Masterbuilt Sklar Bass I (4-string)

Dingwall Leland Sklar Signature Model (5-string)

Amps

Euphonic Audio iAMP Doubler II

Euphonic Audio Wizzy-112

Effects

Boss OC-2 Octave

Strings and Picks

GHS Custom Bass Super Steels (.045–.105)

Is there anything you’re not good at?

The only stuff I really suck at, because of some hand and wrist injuries, is slapping and popping. So, if I get a call for a Louis Johnson tribute, I go, “I’m not the cat for that project.” I’ll drop a couple of names of guys who can smoke that down so easily. I don’t throw myself in harm’s way because I don’t want to be embarrassed and I don’t want a project to not be as good as it can be.

What made Billy Cobham’s Spectrum work so well?

What made that record really stand out were the grooves. They needed to be held down while Billy, Tommy [Bolin, guitar] and Jan [Hammer, keyboards] blew on top of it. Every time I go do a clinic, that’s the first thing guys talk about. It’s funny, for something that went by so fast, all these years later, to still have such strong legs. I get guys that want to jam “Quadrant 4” or “Stratus,” and I go, “You’ve got to understand, I played this once in 1973 and you guys have eaten it up and played it in clubs for years now. I have no idea how the song goes or what key it’s in.”

When you went out with Billy and did the 30th anniversary tour, did you have to literally sit down and relearn those songs?

All of it, and man, we just flew by the seat of our pants in the studio. It was literally one or two takes of everything and we were done. So, it’s funny when you get the guys who are uber-geeking all this stuff and they want to play it. Every time I’m around Clint Black he immediately wants to play James Taylor songs and I go, “I haven’t played that song in a long time. You sit home and practice with it while I’m at work doing something else, so I can’t be of much help here.” [Laughs.]

Do you consider yourself lucky?

I always pinch myself—everyday. I just think how lucky I am. I mean, I’ve worked hard and I don’t deny the effort I’ve put into it. But I feel very fortunate, because I know talented players who haven’t had the opportunities open up that I was fortunate enough to have. I never take it for granted. I’m not blasé about this at all. I’m deadly serious every time I take my bass out and sit down to play. I really try to give it my all.

What keeps you inspired?

The thing that’s helped me a great deal is that I’ve been privy to so many assorted styles and genres and artists as compared to somebody who’s in one band their entire career. I join a different band almost weekly when I’m doing studio work. And you owe it to that project to treat it as though it’s your band. I get real excited. I’m very vocal in the studio with ideas and thoughts. I don’t care if they use them, but I feel it’s imperative to do more than just bring a bass and sit there and play. I think about arrangements. My personal thing I always say is, “Everything I do is etched in mud.” I’m not possessive about parts. If somebody comes up to me and says, “That’s a cool idea, but I think we’d rather do this....” I go, “Fine, I’m good with that.” At the end of the day, I’m leaving that project and moving on to another one, but that could be the only day this artist gets to make their mark, so you give them all you’ve got.

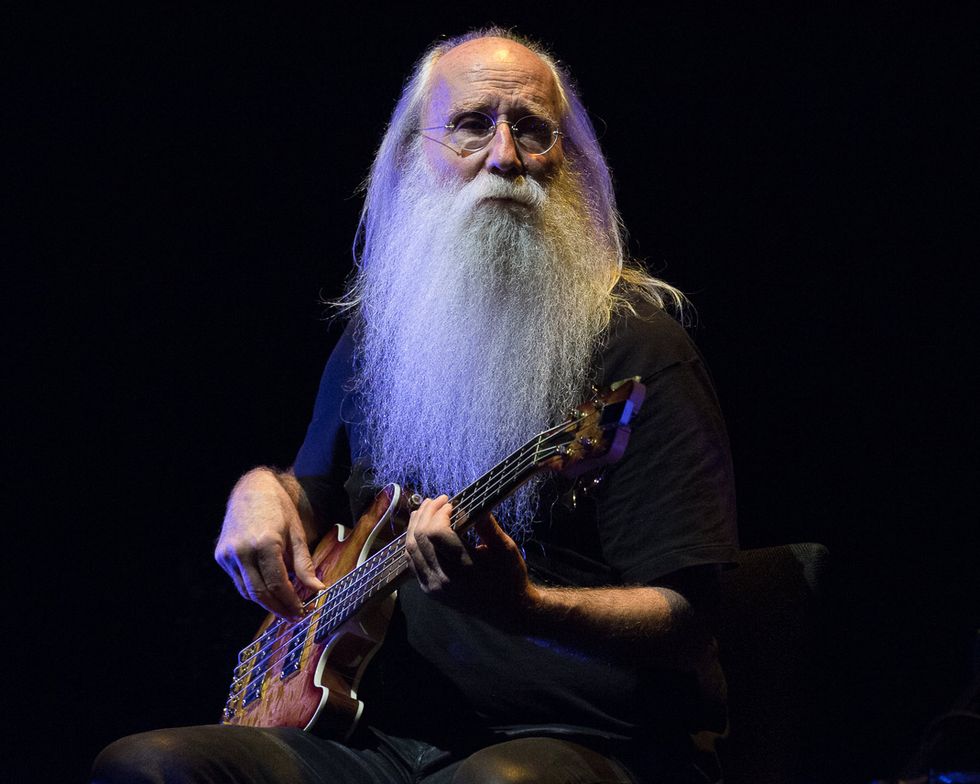

Aces of bass Lee Sklar, Jonas Hellborg, and Steve Bailey play a rare summit in Frankfurt, Germany, performing a tune they cowrote called “Jostle.” Sklar is playing one of his signature Warwick models.

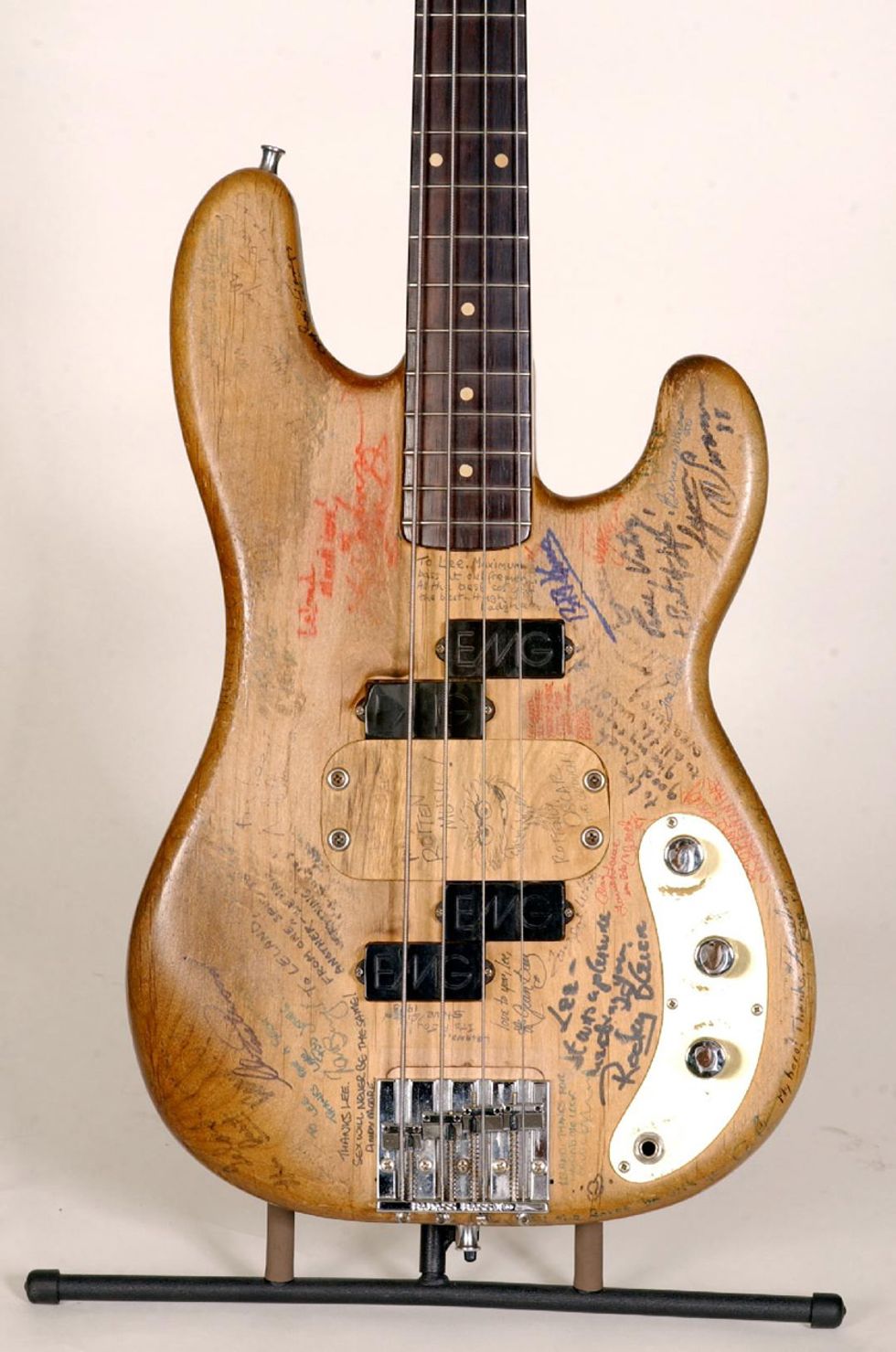

The Story of “Old Frankenstein”

Lee Sklar’s main bass was an experiment that’s since been autographed by world-famous celebrities, athletes, and musicians (see photos) and used on 80 to 90 percent of his touring and recording dates. It was put together by John Carruthers at Westwood Music in L.A. in the early ’70s.“This was around the same time Charvel first started,” Sklar recalls. “They were doing all these alder replacement precision bodies. I went out there and ended up hanging about 12 of these bodies by a wire and thumping on them, and one of them had this incredible resonance to it, so I bought it.”

He took that and a ’62 Precision neck to Carruthers. Not being “a Precision guy,” he and Carruthers made a template of a neck from a ’62 Jazz bass that Sklar owned. They then ripped the frets out of the Precision neck and reshaped it into a Jazz neck. “While that was going on, I was walking around the shop and saw all this fret wire, spools of it, hanging on the walls, and I go, ‘What’s this wire?’ And he said, ‘That’s mandolin wire.’ And I said, ‘Let’s try that.’ And he said, ‘That’s not going to work on a bass.’ I said, ‘Let’s try it. If it doesn’t work, I’ll pay you for a re-fret.’ Needless to say, there was no re-fret.”

Dave Borisoff from Hipshot gave them the first prototype set of his Bass Xtender tuning keys and Rob Turner at EMG provided them with his original P-bass pickups. “We got two sets and put them where jazz pickups would sit instead of the P-bass routing. We also flipped the pickups, so the A and E signal would be closer to the bridge. The first time we plugged it in, it was so even-sounding. And we used 18-volt circuitry, so we were able to save that cavity rather than routing another hole.” The bass was completed with a Badass II bridge. “It was an experiment, but as soon as we plugged it in, we were like, ‘Are you kidding?’”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)