There is something endearing about the way J. Micah Nelson talks about his acoustic guitar, describing it in ways that are far from geeky. He says his Martin, whose model number he doesn’t know, is “three-quarters size,” with “a lot of frets on it” and that it’s made from “kind of a darker wood.” An internet search reveals that the Martin is in fact the full-size 000-15M, with the standard 14th-fret neck junction and mahogany soundboard, back, and sides.

Given the sharp songcraft and uncanny guitar moves on Nelson’s latest album, Window Rock, which he recorded under the name Particle Kid, it’s clear that the singer-songwriter places far more importance on his musical vision than the technical specifics of his instruments. And the depth of Nelson’s music makes sense when you consider where he came from.

Micah, who is 29, is the youngest son of Willie Nelson, and he and his older brother Lukas pretty much grew up on their father’s tour bus. Micah made his live debut at the age of 3, when he joined the elder Nelson onstage, playing the harmonica. He has since pursued a musical life that, while for the most part is outside of the outlaw country tradition that his father helped establish, shares an iconoclastic edge.

Some of Micah Nelson’s earliest recordings were with the experimental Los Angeles-area band Insects Vs Robots. He’s also teamed forces with Lukas Nelson in the band Promise of the Real and has toured and recorded with Neil Young, who has acted as a mentor to both brothers. But at the moment, Particle Kid is Micah’s main project.

While Particle Kid’s previous albums had a sort of bedroom-recording feeling with their sonic collages, Window Rock has more of a live-band feel, as Nelson’s Insect Vs Robots colleagues Jeff Smith and Tony Peluso handle bass and drum duties, respectively. The album’s psychedelic vibe is enhanced by nonstandard guitar tunings, some choice effects pedals, and the occasional sounds of overdubbed cassettes.

During a recent European tour, Nelson connected via Skype to talk about the lessons he’s learned from his father and from Neil Young, his growing collection of EarthQuaker stompboxes, and the musical applications of frog calls.

What has your father taught you about playing guitar?

When it came to guitar, one thing that we both really connected on is Django Reinhardt. My dad worshiped Django Reinhardt, and his whole guitar sound was modeled after Django’s—those Gypsy jazz scales, those kind of weird jazzy Django chords, and these different songs, “Nuages,” “I Never Cared for You”… my dad taught me how to play those songs, and that kind of feel has definitely influenced everything I’ve done.

So that had a big influence on my playing, and that kind of thinking-outside-the-box approach that Django had, my dad has. I play in his band sometimes, and I just start laughing, listening to his playing. It’s so ridiculous. He’s like the Jackson Pollock of guitar. He’s just flying around like you never know. It doesn’t make any sense what he’s doing, but it works somehow. It’s really kind of punk rock, actually, the way he plays, which I love.

Window Rock has so many compelling guitar sounds, both acoustic and electric. What instruments did you use to record it?

The acoustic I played is a Martin. It’s made in Nazareth. Honestly, I don’t even know what model it is. It’s three-quarters size, it’s got a lot of frets on it, and it’s kind of a darker wood. What happened is my brother has one, and I was hanging out in the back of the tour bus one night and just started playing it. And I was like, man, this feels so good. I got to get one of these. And I went into Truetone Music in Santa Monica to get something completely different, and I saw one on the wall, and I was like, “Oh, yeah.” And I picked it up and I played a song that I had just written and realized that there was nothing resisting anything to me. It just felt so effortless, and the feel of the neck, and the action, and the amount of frets on it. It was exactly what I needed, because I’d been playing this Taylor GS Mini for years, and I just felt like I was at a point where I needed to get a somewhat normal-sized guitar. And I got this Seymour Duncan pickup, and it’s the one that has the blend between the condenser mic and the pickup. And it’s one of those guitars where I have to try to make it feed back, which is rare for me.

The electric guitars I used are Gandalf the Grey, which is a Gibson Melody Maker, with those P-90s in it. It’s not a really old guitar—I think it’s probably from 1990—it’s just been through a lot ever since I got a hold of it. A former girlfriend of mine got it from her sister, whose friend won it on a TV show, or something. She was trying to sell it on Craigslist, because she needed some money. And she said, “Hey, could you pose with this guitar? I’ll take a picture for a Craigslist ad.” And I was sitting there noodling on it, and I just looked up at her. I was like, “How much do you want for this thing?”

Both that one and my Telecaster, Sister, had this stupid piss-yellow color, and I ended up painting both of them and staining them myself. And on the Gibson, on Gandalf the Grey, I put this [Seymour Duncan] Antiquity [II] Firebird bridge humbucker in the neck. I also took out the tone knob, and so it’s just a toggle switch and a volume knob. It’s really simple. There’s not a lot to think about, and it’s super light—it feels like a piece of balsa wood or something. But it’s sturdy.

Then Sister Lou is the Telecaster that Neil [Young] got me in France a few years ago, because I needed a backup guitar, as I was always breaking strings onstage. It’s such a great guitar, but I didn’t really play it for a long time. It was just sitting there in the studio. And when I started doing a lot of these alternate tunings in my show, I was like, “Well, I need an extra guitar that’s already in this tuning. Oh, yeah, I have that Telecaster.” And this is a guitar Nash makes—it’s a ’54 Tele relic with Lollars and this really fat C neck. I have these long, spindly, kind of old man fingers, and it’s really comfortable, that fat neck. Because if the neck’s too thin, I feel like I’m cramping up, or I get arthritis, or something. It actually has become my main guitar, whether I play with Neil or my band, and it’s all over this record. And it’s such a bright, clear, crisp tone. I’m doing a lot of fuzzed-out, kind of grungy-textured, psychedelic stuff. And even through all the dirt and fuzz, there’s clarity to it, which I really like.

TIDBIT: Micah Nelson’s previous Particle Kid releases were largely self-contained albums, solely arranged by Nelson. Window Rock represents the sound of Nelson’s touring trio, which is Nelson on vocals and guitar, Jeff Smith on bass, and Tony Peluso on drums.

And I think that’s all the guitars on the record. There might be moments of this PRS McCarty model. It’s a semi-hollowbody electric guitar that my friend gave me. I started the record on that guitar, and then kind of halfway through, I switched over to Gandalf the Grey. I think the solo on “Radio Flyer” is on the PRS.

What about amps and pedals?

On this album, I’m playing either a ’63 Princeton or a Magnatone Twilighter Stereo, one of those newer Magnatones. As far as pedals, for drive, I’ve been using the ZVEX Box of Rock. It’s a preamp boost and then it’s also got a button that’s straight-up distortion, like a Marshall cranked up to 10, and you can modulate it with a knob. I’ve recently been using stuff by EarthQuaker. I have the Pyramids, which is a flanger. You can get not only a classic flange but all kinds of laser-blast, sort of Star Wars video-game sounds. And I have the Bit Commander, which is a monophonic synth. It’s like an Atari video game on steroids and acid, and then it’s also a fuzz and an octave divider in one. And it’s got a sub-octave—everything. That one’s really fun, it breaks up in this 8-bit Nintendo sort of way.

And the Rainbow Machine, another EarthQuaker one, is a polyphonic synth delay that’s like this ridiculous madness, nonsense machine. If you just turned it on it’s like this delay and pitch modulator, but then if you hit this magic button, the second signal feeds back in on itself, and you can modulate the volume of each signal. So it does this crazy feedback and you can make it modulate up or down ... it’s totally absurd. That’s like the end-of-the-world-kind-of-trembling-away pedal.

I’ve also got the Strymon El Capistan, which is basically a space-echo kind of sound. It’s in this tiny pedal and you can make it sound like warbly tape, or a little cleaner, and then you can make it really get spacey or make it kind of a tight slapback. But it sounds really more tape-y, which I like. And sometimes I just leave it on, depending on the acoustics of the room.

Oh! I also have the Electro-Harmonix Mel9, which basically emulates a Mellotron. You’ve got a knob which lets you choose between different choirs and a cello, flute, brass, and an orchestra, and you can blend it with your guitar sound and modulate how long you want it to decay and sustain and everything. That’s a fun one. And then I have a Cry Baby wah and a TC Electronic Ditto X2 looper, which I occasionally use.

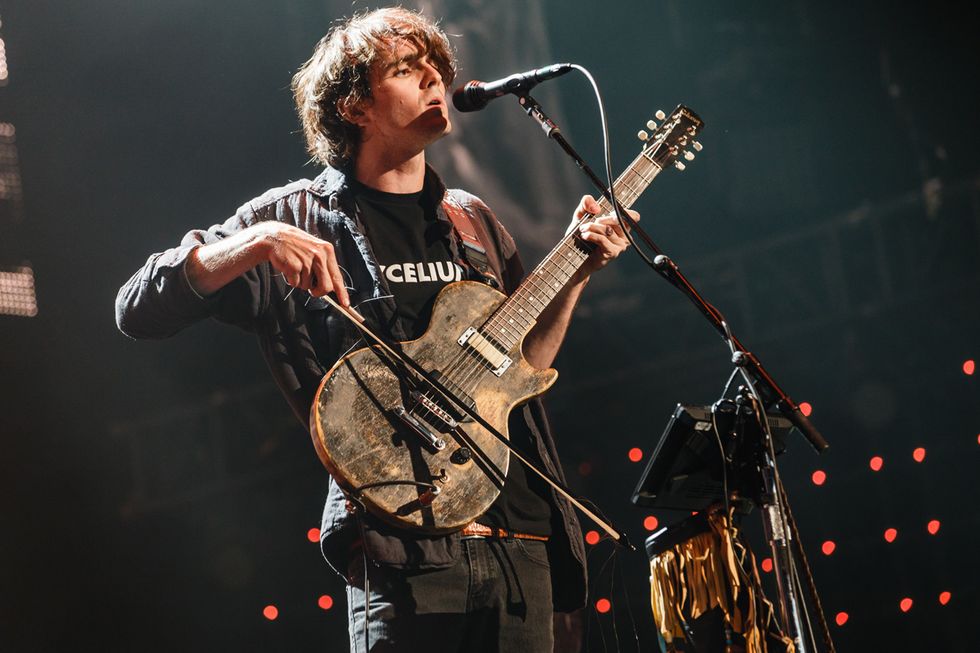

Gandalf the Grey is the nickname Micah Nelson bestowed to his 1990s Melody Maker, which he refinished himself because he didn’t like the “piss-yellow color.” Here he plays Gandalf with a bow while onstage with Neil Young at Farm Aid in 2016 in Bristow, Virginia. Photo by Matt Condon

You really seem to like those EarthQuaker pedals. Are they prominent on the album?

Honestly, I wish they were. There will probably be a lot more on the next record, because I connected with them towards the end of this album. At this point they’re pretty involved in my live sound, but they’re only on these little moments at the ends of certain songs. I know the Rainbow Machine is on “Hollows,” though kind of sparingly.

The album has some really nice chordwork, like the major 7ths on “Straight Line.” Where does your sense of harmony come from?

So many places, honestly. I grew up loving the Beatles and Sonic Youth and Neil Young, obviously Radiohead, the Pixies, and all the classic-rock stuff, Pink Floyd. I mean, I could name bands for years. And a lot of those unexpected harmonic relationships between the notes and the chord changes come out of these alternate tunings I like, which is partially inspired by Neil. You know, he’s been a mentor to me and he’s shown me some really interesting alternate tunings that he uses, and weird chords—even in some of his best songs.

And probably even more so, Sonic Youth. Their influence is huge on me and their use of alternate tunings, and just the uncanny things that can happen with that, where just by tuning a couple of strings differently the whole dimension can get opened up with a floodgate of songs. And a lot of the songs on this record were because of that.

What are some of your favorite alternate tunings?

There’s this particular tuning I tend to keep the Gibson in, and it’s inspired by the charango, which is an instrument I discovered in Ecuador back in 2010. It’s this Andean folk lute with 10 strings, something between a ukulele and a mandolin. They make them out of jacaranda wood mostly these days, but originally they were made out of [the shells of] armadillos because it was available and it was small enough to hide under your poncho from the Inquisition and stuff.

And so I started playing one of those—it was tuned a minor third down from the traditional tuning of the charango, but it was the tuning that I found it in. I just started playing along to records and with other people, figuring out what shapes made what chords. I think the tuning was F–Ab–D–G–D, so it was five double-string courses. The notes would float through each chord change and give it this really cinematic kind of feeling.

Eventually I decided to tune my guitar like that, which opened up a whole new chapter of songwriting for me. A lot of the songs on that record are in that tuning. From there I discovered D modal and C modal, and those open folk tunings like Bert Jansch and Pentangle and the Incredible String Band used. And when I started going minimalist with my music and journeying into this sort of method of stripping things down to their bare essentials, I wanted to take an otherwise generic two-chord song and give it some extra quirkiness to spark a different kind of emotion out of it.

Which songs on the album are in the charango tuning—and how do you spell the tuning?

“Radio Flyer” is and so is “Straight Line,” the song you mentioned, and “Hollows.” Definitely those and also “Backwards.” Actually I had to do it a half-step down from the charango tuning, because the high string kept breaking because it was so high. So it’s actually E–A–C#–F#–C#–F#. I confuse myself sometimes with all the weird tunings, but I understand them. I don’t know if they make sense to my guitar-tech guy.

You mentioned going minimalist—is that something inspired by Neil Young?

Oh, absolutely. I mean, among other things, it’s easier to tour with a three-piece. And challenging myself to play a memorable, engaging show of songs with nothing but a voice and guitar, or voice and piano—that drove me to minimalize.

And definitely playing with Neil. I’ve always loved Neil’s music and been inspired by him as an artist and as a thinker, and I really relate to the way he approaches things. Playing in a band with him and playing his music—it’s a constant exercise of less is more, you know? It’s like going balls-out when the moment is needed for that, but at the same time practicing restraint.

Guitars

1990s Gibson Melody Maker

Martin 000-15M

Nash T54

PRS McCarty 594 Hollowbody II

Amps

1963 Fender Princeton

Magnatone Twilighter Stereo

Effects

Dunlop Original Cry Baby Wah

EarthQuaker Bit Commander

EarthQuaker Pyramids

EarthQuaker Rainbow Machine

Electro-Harmonix Mel9

Strymon El Capistan dTape Echo

TC Electronic Ditto X2

ZVEX Box of Rock

Strings and Picks

Medium-to-heavy string sets, any brand

Dunlop Tortex Standard .60 mm picks

Neil cuts to the core. His songs are only the notes that need to be played to make you cry and make that emotion—whatever it is that he’s expressing—come across. And it has nothing to do with technicality or shredding a million notes. It’s not sports, it’s music. It’s what feelings sound like. He’s the master of brilliantly composing and stripping things down. Being able to do that, like play a whole show of his songs with just the piano or guitar and have it be so emotional and incredible.

It’s also with his sounds, with the texture and tone of his guitar—I mean, he is like a tone Jedi. He’s tone-questing all the time to get the sound he knows. I remember in the beginning of touring with him, he was trying to get back to this tone that he had in the ’90s. He’d be standing in front of a tweed Fender Deluxe with the tech back there switching tubes out, and he’d be like, “Okay no, switch that preamp tube out. Okay, no. Put that first tube back where the other tube was.” For like 25 minutes, you know? And then at the end of it, he’s like, “No, no. It’s not right. We need those German vintage tubes, and we have to have Instrument 2 with the volume up to 9 so it sucks the power out of Instrument 1 so that it compresses the top end when I pluck.”

I’m like, holy fuck—this is Jedi training. I’m just absorbing all this. And it’s like the kind of thing you might not quite understand or be aware of the nuances until you hear it for real, how it’s supposed to sound. And then you’re like, holy shit—I get it now. And that’s the importance of tone quest. If you can get your tone to be that musical and powerful, then you don’t need more than three things happening at once in a song. So definitely he’s taught me a lot when it comes to minimalism, for sure. And you know, sometimes directly, sometimes by explaining things, but most of it by observation, by osmosis, and just by the experience of playing with him for years.

While Window Rock feels live, there’s subtle layering and speech samples, like on “Straight Line.” Which comes first for you—the sonics or the song?

Definitely the songs on this album. Before, like years ago when I first started experimenting with recording, it was sort of the opposite. I’d record things from wherever my group was traveling and I would chop things up and make a song out of that field recording or sampled thing. Which I would never be able to recreate live without a sampler or a laptop.

But since then I’ve really grown to appreciate the power of songs and the timelessness of songs, and how songs can be vehicles for all of those cool sonic textural ideas. You know, they’re like the spaceship. And even like a simple three-chord song, if you can play it totally naked with nothing extra and it’s still catchy and cool, then all of that sonic stuff can still apply. You can replace the guitars with a bunch of recordings of frogs from your camping trip that get pitch-shifted into the notes. If you have this great song underneath it, then it works no matter what.

Micah Nelson puts his customized Melody Maker through its paces with his band Particle Kid during Farm Aid 2018 in Hartford, Connecticut.

Watch sons Micah and Lukas Nelson play “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” with their father, Willie Nelson.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)