Many listeners’ first exposure to the unique, slithering guitar sound of Harvey Mandel came when the Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff” hit the airwaves in 1976. But Mandel’s story begins more than a decade earlier, when young white guitarists roamed Chicago’s blues clubs, learning to play at the feet of legends like Buddy Guy, Otis Rush, and Magic Sam. The release of The Paul Butterfield Blues Band in 1965, with its back-cover exhortation to “play it loud,” and the group’s East-West in 1966 showcased the incendiary playing of one of those nascent guitar heroes, Michael Bloomfield, whose raw performances on both records spoke to a new generation of players.

Harvey Mandel was also on the Chicago scene, cutting his teeth sitting in with blues legends. “Bloomfield was more on the South Side, and I hung more at the club Twist City, which is the West Side,” says Mandel. Born in 1945, he was a few years younger than the Butterfield Band guitarist, but by his late teens he was consistently jamming with the likes of Buddy Guy. “I wasn’t legally allowed in a lot of clubs because I wasn’t 21, but the owners didn’t mind,” he says. “They would sneak me in and out, making sure no one fed me liquor so they wouldn’t lose their licenses.” Shortly after becoming “legal,” Mandel made his recording debut on Stand Back! Here Comes Charley Musselwhite’s Southside Band, with a singing tone already hinting at the sustain that would help define his sound.

To many suburban blues guitarists, Stand Back was almost as influential as the Butterfield records, but because it was released in 1967, Mandel’s emerging style was overshadowed by Clapton’s work with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and the arrival of Jimi Hendrix. Still, Bill Graham deemed the Musselwhite band worthy to share a bill with Bloomfield’s Electric Flag and Eric Clapton’s new group Cream at his San Francisco-based Fillmore West. “I ended up staying in San Francisco, because after that show the group disbanded and everyone went their own way,” Mandel recalls.

a Rolling Stone.”

There, the guitarist met Abe “Voco” Kesh (Keshishian), a radio DJ and producer for the Mercury/Philips labels. A fan of the Musselwhite band, Kesh had just produced a No. 1 record for Blue Cheer. This let him get Mandel a solo deal with Phillips without so much as an audition. His first solo record, Cristo Redentor, in 1968, contained many of the markers Mandel would revisit over more than a dozen records and almost five decades: funky grooves with strings and horns filling out the sound, along with psychedelic production techniques like guitars panning across the stereo spectrum and flipping the tape over to achieve backwards guitar effects. Even without recording tricks, Mandel’s distinctive licks seemed at times to be going backwards, creating the serpentine sound that earned him his nickname, “Snake.”

The next year saw the release of Righteous, cementing the eclecticism that would mark all of Mandel’s music, ranging from the clean tones on Cannonball Adderley’s “Jive Samba” and the funky “Poontang” to more distorted effects on the swampy “Love of Life” and the slow blues “Just a Hair More.”

One of the most successful blues bands of the late ’60s was Canned Heat, who cracked the pop charts with “On the Road Again” and “Goin’ Up the Country.” Following the release of their fourth record, original guitarist Henry Vestine quit after an onstage argument with bassist Larry Taylor at the Fillmore West. The next night Mandel and Mike Bloomfield sat in with the band, after which Mandel was recruited as Vestine’s replacement—just in time for Woodstock.

Mandel left Canned Heat in 1970, but soon joined Larry Taylor in British blues legend John Mayall’s band to record USA Union. For that drummer-less album, the guitarist fully abandoned distortion and sustain for a more country-ish clean tone, leaving the majority of the soloing to Mayall’s piano and Don “Sugarcane” Harris’ electric blues violin. Mandel and Harris would briefly join forces a few years later for the group Pure Food and Drug Act, but not before the guitarist recorded one of his best solo records, 1971’s Baby Batter.

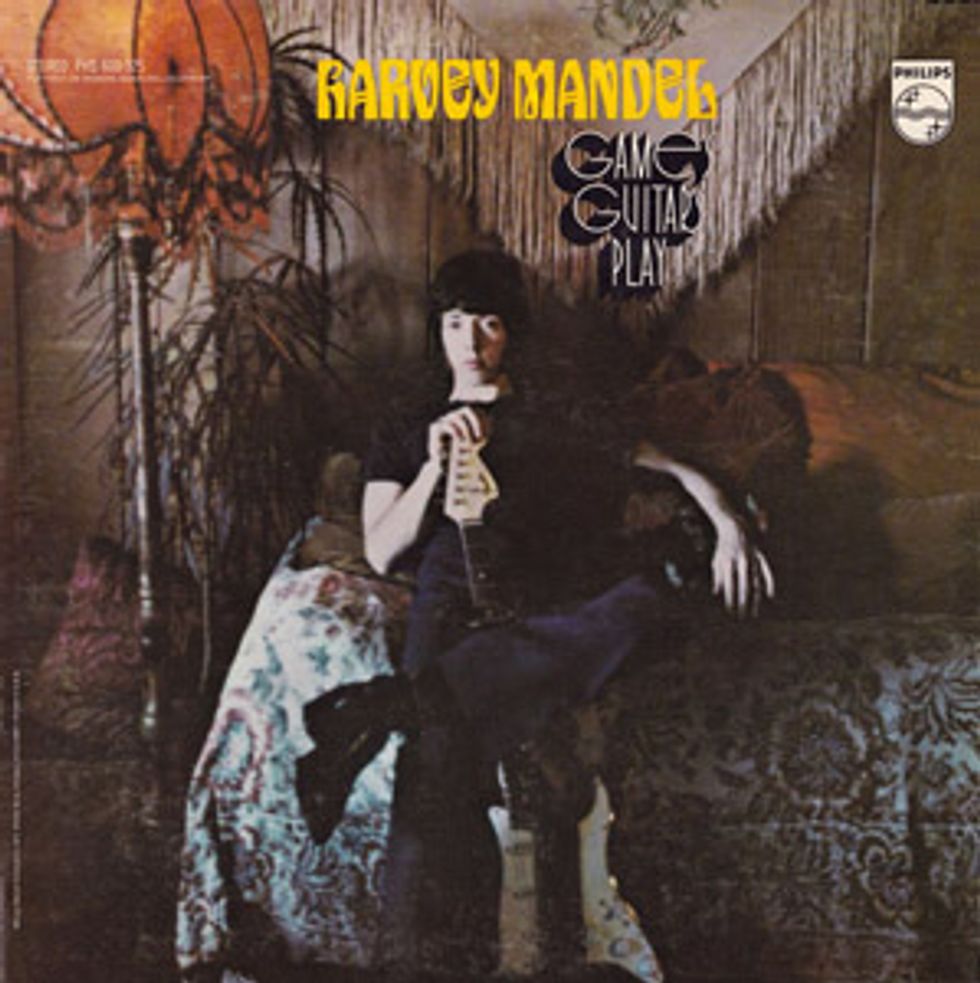

When he cut 1970’s Games Guitars Play, Mandel was wrangling a Fender Stratocaster. The album includes bassist Larry Taylor and covers of “I Don’t Need No Doctor,” which Humble Pie would also record live the next year, and “Leaving Trunk,” Taj Mahal’s take on Sleepy John Estes’ “Milk Cow Blues.” The LP is now part of the Snake Box reissue set.

For The Snake, released in 1972, the guitarist added some new sounds and techniques. Uni-Vibe modulated tones are prevalent, while the song “Lynda Love” offers pull-offs on open strings that create wide intervallic jumps. Mandel further expands his technical palette on 1973’s Shangrenade, delivering an explosion of two-handed tapping a full five years before Van Halen’s first record.

The year 1976 brought the guitarist’s famous Rolling Stones audition, which resulted in Mandel appearing on two singles from the Black and Blue album, “Memory Motel” and “Hot Stuff.” His tasteful melodic licks on the former enhance the tune, but it is his limitless sustain and backwards-sounding licks on the latter that show the added colors and creativity Mandel might have brought to the band had they not opted to go with Ron Wood’s virtual cloning of Keith.

In the subsequent 40 years, Mandel has toured with versions of Canned Heat and continued to make solo records, including his most recent, 2016’s Snake Pit. This release finds the guitarist at the top of his game, mostly fingerpicking his heart out, despite spending the last few years fighting off cancer and undergoing a series of operations. Last year also saw the release of Snake Box, a set of five full Mandel classics—Cristo Redentor, Righteous, Games Guitars Play, Baby Batter, and The Snake, along with a bonus disc, Live at the Matrix.

Surveying the collected works and latest release, as well as interviewing the man, reveals a portrait of an artist who developed a personal voice early on, yet continues to grow, willing to incorporate new sounds, skills, and technology as long as they help him achieve his vision.

Were you born in Chicago?

I am from Chicago. I just happened to pop out at the wrong time, when my father was working in Detroit, but I never really lived there. I was an infant when we moved back to Chicago.

How did you start playing guitar?

I was going on 16, jamming on bongo drums with this guy who played the guitar—a kind of a beatnik thing. I asked him to show me a chord, and from that moment I was hypnotized. My dad got me my first instrument, which was a $16 Harmony acoustic. A guy in school showed me how to take a phonograph cartridge, put it on the guitar, and drill a hole in a radio to use it as an amplifier. That became my first electric guitar. When my dad saw I was that inventive, he took me to Sears, where I got a Silvertone with a Silvertone amp. Every few months I graduated from one guitar to the next, until I went through all the Strats and Gibsons. I have been mostly playing Parker guitars for the last 12 years.

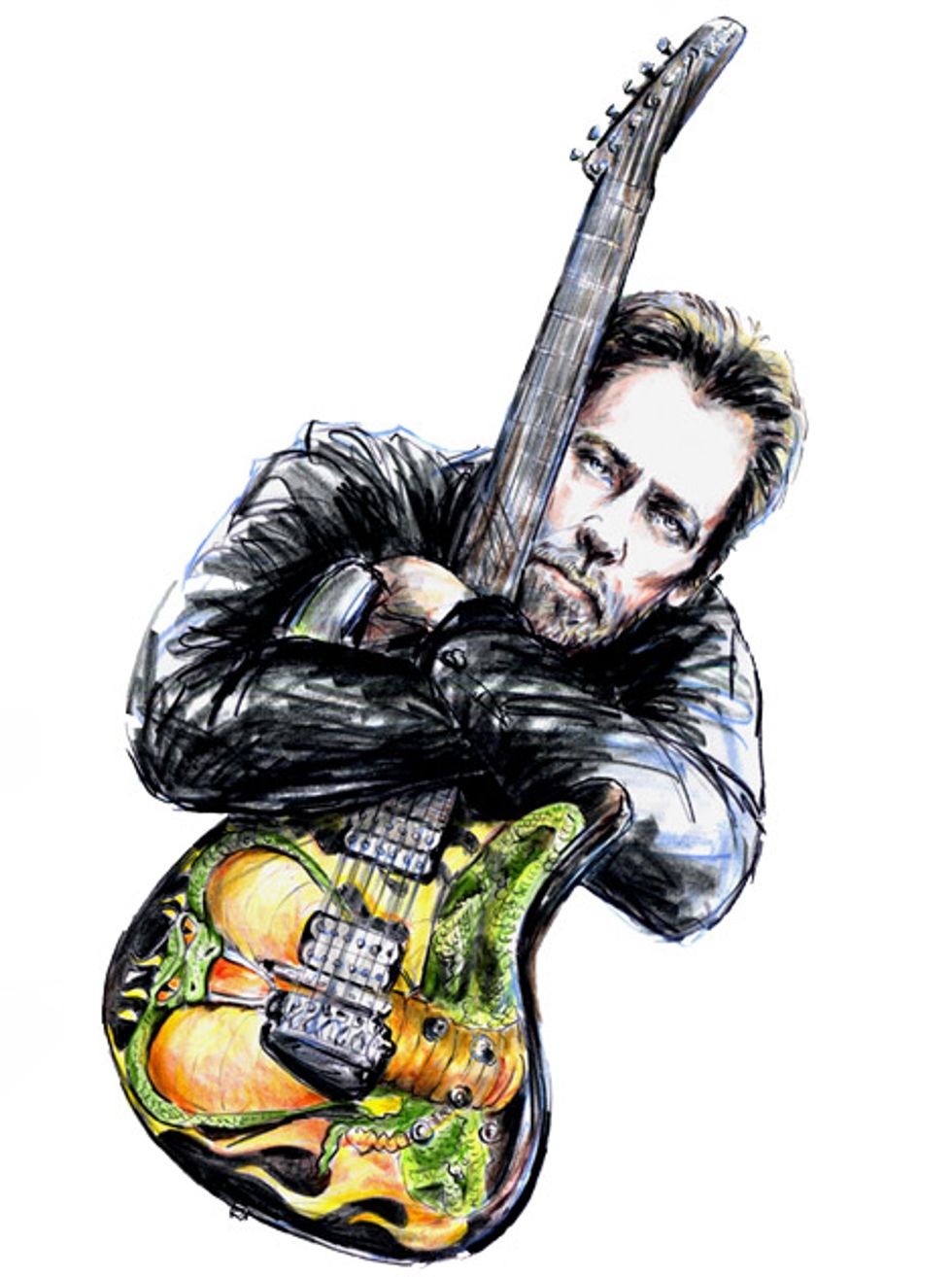

Live, Mandel employs modern stompboxes and a VG-99 to reproduce effects he created decades ago in the studio. His Parker Fly Mojo sports an aptly psychedelic finish—flames and a snakeskin-patterned lower bout.

Did you come up in the same Chicago scene as Mike Bloomfield, Paul Butterfield, and keyboardist Barry Goldberg?

Barry Goldberg and I played in a couple of groups together, including on Charlie Musselwhite’s first record. I didn’t know Mike Bloomfield well. We jammed a couple of times. We were all pretty much from the same era, playing a lot of the black clubs.

Early on, you covered tunes by saxist Cannonball Adderley and pianist Horace Silver. Was jazz a big influence?

I listened to all kinds of stuff back in those days and it would all have some influence. Even though I am primarily a blues-rock player, I still like jazz. I can do some within my style. I also like country. For a while I did nothing but country licks. I actually played with a country band for about six or seven months. Having those other influences mixed in makes my blues and rock playing better.

How do you do some of your more extreme string bends?

I have the action set where I can slip the G string or B string underneath the D and A string if I have to. That’s the only way you can do certain bends or vibratos. I use .009-.042s, so my E, B, and G are light enough to push into the other ones.

You seem to both push and pull the strings.

I do every type of vibrato and bend you have ever seen. I have my Eric Clapton vibrato. There is the Albert King vibrato, which is pulled down. There’s my Otis Rush vibrato, which is real smooth. When I first started playing blues, I spent lots of time perfecting those techniques.

What led you to seek almost infinite sustain?

I was trying to imitate horn, violin, synthesizer, harmonica, and steel guitar sounds. You get an idea in your head and you find a way to do it. Now, they have 500 different pedals to give you sustain, distortion, and fuzz. When I started we had to get it from an amplifier. We had to figure out the proper amp to use and the way to set it. When I did the Baby Batter record, I was using a Bogen PA amplifier. I took out one or two of the tubes, so it wasn’t real loud, and fed it into a 12" speaker. To this day that is one of my best sounds. I did all kinds of crazy experimenting with different stuff. Now, I’m an expert on effects so I can consistently get the magic sound. Back in the day it was hit or miss.

You also experimented with backwards guitar sounds.

I started by flipping the tapes over. It’s all in learning how to play to make the sound natural and make sense with what you are doing when you reverse it. You can’t just reverse anything and expect it to sound good. Now I use certain effects that emulate the backwards sound.

Sometimes you sound like you are getting a reverse sound without effects.

I became able to sustain those notes to let them bend down and do all these weird little twists and turns that you get when you do the backward tapes. I was always emulating that sound.

Was 1973’s Shangrenade the first time you really started two-hand tapping?

That entire record is tapping.

What led you to that technique?

When I was in the Pure Food and Drug Act, the other guitar player, Randy Resnick, did a little tapping. Others had done it before, but that was the first time I saw it. I just took it and did my own thing. Van Halen got the credit for tapping, but I was definitely the first rock guy to do it on a record. Nobody realized I was tapping on Shangrenade. They thought I was a jazz player with long fingers who was able to do these incredible intervals.

Tell us about the Rolling Stones’ audition.

I was living in Los Angeles, when I got a call at 3 or

4 o’clock in the morning from Mick Jagger. I thought it was somebody goofing around, but after I talked to him a minute or two I could tell it was really him. He said, “I’d like you to come play on this record. We’re in Munich, Germany. I want you to fly out tomorrow.” The next day I got a ticket, took my stuff, and went there.

I knew at the time it was an audition, because Mick Taylor had just left. He wasn’t part of the showmanship stuff. He didn’t jump around and go crazy like Jagger. He stayed in the background and just played cool guitar. Jagger wanted me because, like Mick Taylor, I would play fancy guitar licks in the background and let them do their thing. Unfortunately I lost out to Ron Wood because Keith Richards wanted to keep the band all-English. Keith grew up with Ron and they were buddies. Still, I did come real close to becoming a Rolling Stone.

Harvey Mandel’s Gear

GuitarsParker Fly Mojo with DiMarzio pickups

Amps

Fender Hot Rod DeVille 4x10

Effects

Keeley Fuzz Head

Keeley Compressor

Roland VG-99

Strings and Picks

Dean Markley (.009-.042)

Dava medium picks

How had Mick heard of you?

We crossed paths somewhere when I was with Canned Heat. So, through somebody, he got my number.

How did the Snake Box set come about?

My manager, Timm Martin, from Out the Box Records, is also in charge of the Chicago Blues Reunion Band, which is Barry Goldberg, me, and some other Chicago players. He had a connection with Cleopatra Records and they made an offer.

Snake Pit is your first studio record in over a decade. Why now?

I guess people started getting interested in me lately because of my past notoriety and the illness that I was going through. Josh Rosenthal [of Tompkins Square Records] reached me through my manager and came up with the offer to do this record at Fantasy Studios. All the tracks were one to two takes live, but it was recorded with earphones in separate rooms. I did some conducting through the glass. The musicians were really good. Once I told them what to do, I could just sit back and play. Despite the fact that I have gone through a bunch of medical weirdness these past few years, I can play better than ever. That’s the only thing I can still do in my old age. [Laughs.]

What pedals are you using these days?

I play through a Roland VG-99 and some Keeley pedals I keep on the side, like fuzz, delay, and compressor. The VG-99 is great because it has a million effects built in. I can sit there and create a bunch of my own patches, so I can have the perfect rhythm sound, the perfect Jimi Hendrix sound, and a perfect backward tape sound at the flip of a button. I use it mostly for the effects, through a Hot Rod DeVille 4x10. Sometimes I will run one of its amp model effects and still run it through an amp.

On “Buckaroo” there’s a sound that is like a wah-wah, only not quite.

There is a ribbon controller on the VG-99 to modify effects parameters. I did that with my finger on the controller. I used it to filter the sound. It was the first time I ever did it, just for fun. It produces a tone you can’t get with the regular wah pedal.

A lot of your tracks over the years resemble what they started calling “acid jazz.” Many of those old acid jazz records ended up as samples on hip-hop records. Have your records been sampled?

Sure. They can take certain chords, a good beat with a magic rhythm, and do all kinds of crazy stuff with it. I know that has happened for sure.

Have you gotten any kind of remuneration from anyone?

Are you kidding?

How are you doing health-wise?

I have been over the cancer for the last couple of years, but have been limited because every four to six weeks I had to go for reconstructive surgery. One or two more operations and that will be done, and then I can concentrate on touring and performing. It’s been like a never-ending nightmare, but now the end is finally in sight and I can concentrate on getting my full strength back. I would say in the next six months to a year, I should be back in full swing again.

YouTube It

Caught live in Lucille’s restaurant at B.B. King’s Club in New York City, Harvey Mandel is in top psychedelic form on his Parker Fly Mojo, conjuring his way through backwards guitar lines and vibrato-drenched riffs as he dips his toes into the traditional spiritual “Wade in the Water.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)