The Wood Brothers, who are Oliver and Chris Wood on guitar and bass, respectively, along with Jano Rix on drums, are no strangers to serendipity, which was key to the recording of their latest release, Kingdom in My Mind.

The happy accidents started with an opportunity to move into their own studio. “Brook Sutton is our engineer, and we recorded a good part of our previous record with him at his old studio,” Oliver says. That was 2018’s Grammy-nominated One Drop of the Truth. “At some point last year, he lost the lease to his old building. We figured, ‘Why not go in on a place together? We get a little more square footage, help out paying the rent, and he can help us make our next record or records.’ So it is a co-op situation with our favorite engineer, and it works out great. He’s got a fully working studio when we’re not around, but when we’re there, we have the run of the place. It’s also our clubhouse, where we keep all our gear and rehearse.”

The next stroke of good fortune happened when they gave the new place a test drive. “We weren’t thinking about compositions at all,” Chris says. “We were just having fun playing together, improvising, and jamming, but we were so happy with the recordings of those sessions that we decided to make this record starting with them.”

The result is an album that’s uninhibited and somewhat carefree. It’s still the Wood Brothers—an acoustic/electric, gritty take on roots Americana that’s bolstered by stellar musicianship—but it also features unexpected quirks and oozes an unpretentious, laidback feel. Great examples include the unhurried, loosey-goosey opener “Alabaster,” the infectious porch jam “Jitterbug Love,” and the spacey singalong “Little Blue.” But even the album’s raunchier cuts, like “Don’t Think About My Death” and “A Dream’s a Dream,” benefit from their relaxed approach.

“When you write a song and then work on the music, you play very differently,” Chris says. “Whereas if you do it in the order that we did, you’re much more free.”

That freedom is something the brothers know well, and probably starts with their early exposure to music. “Our dad was, and still is, a great folk singer and guitar player,” Oliver says. “In fact, he has a prewar Martin D-18 that’s just to die for. It’s the most amazing guitar I’ve ever played. Our earliest influence is definitely him—his playing folk songs, simple but cool picking, cool runs, and stuff like that.” The brothers also had established careers—Oliver with King Johnson and Chris as a founding member of Medeski Martin & Wood—before joining forces in 2005.

Fifteen years, seven studio albums, and four live releases later, we spoke with Oliver and Chris about their unconventional approach to recording, their new Kingdom in My Mind, their unusual go-to instruments, and Oliver’s fascination with low-budget gear. Plus, we got an insider’s look at their drummer’s shuitar.

How did your approach to recording Kingdom in My Mind differ from past albums?

Chris Wood: The first thing that happened, before we started thinking about recording or making a record, was we finally got our own studio in Nashville. We have an A room and a B room, and one of them’s big. You can fit an orchestra in there. It’s really a big live space—and the other one’s a little smaller and a little dryer. The first thing we wanted to do was get familiar sonically with the space. We set up in different parts of the studio, just to have fun using our own instruments, improvising, and getting a feel for the space, and it happened to go really well.

Oliver Wood: We’ve always done a lot of improvising in the early stages of making an album. We would do it in a rehearsal space, do a fully improvised jam, not worry about form, and just try to make cool sounds—be creative and let your subconscious listen and play stuff. We’ve always done that, but usually we just recorded it on a phone or something, just for reference later. What was different about this record was that we were in our new studio, with really nice microphones, and we recorded these improvisations at album quality. Whether we were going to use them or not, we had the luxury of doing that. The beautiful thing is we captured some magical stuff we never would have played that way if we were actually trying to play a song. There’s all sorts of magic mistakes and drum fills in weird places, and we just love that. It sounded like an old, messy record to us. We used that stuff, chopped it up, and then wrote songs over it. It was a huge luxury to be able to do that, and, of course, just having your own studio is the biggest luxury of all. We could be really experimental on overdubs as well, and never watch the clock, never worry about the budget, or the time in the studio, or affording a producer, because we produced it ourselves … or the record label looking over our shoulder, because we are the record label. It is the ultimate feeling of independence and it is the most liberating experience.

Did any of those source recordings make it onto the album itself?

Oliver: Absolutely. A majority of the songs are exactly that. The first single we put out, “Alabaster,” was completely that. It was one of the first jams on the first day in our new studio, when we were just trying to figure out sounds and see what it felt like to play in different corners of the room or in different rooms.

TIDBIT: The band’s new album grew out of jams recorded at the Nashville studio they recently built with producer and friend Brook Sutton. “It’s also our clubhouse, where we keep all our gear and rehearse,” says Oliver Wood.

Chris: There are a couple where we reworked it, and added some other sections. “Little Bit Sweet,” for example, is from the original jams from the first day we played in the studio, but then we re-performed that one, so we could add some different chord changes. But the first song, “Alabaster,” is completely the original jam. “Jitterbug Love,” “Don’t Think About My Death” … there are a lot that retain the original jams.

How are you set up in the studio? Do you stand in a semicircle so you can see each other? Do you have the amps in the room with you?

Oliver: It varies from song to song. There are some songs where we are in a circle, we’re all in one room, and we like all the bleeding between the tracks, which is another one of those jam things that’s so fun. That’s what a lot of old records sound like. You can hear things bleeding into other channels and it’s not so sterile and isolated sounding. We did a lot of that, but we also like to experiment.

Chris: A lot of our favorite old recordings, that’s what they do. People are set up in the same room, they bleed, and it gives the recording a certain character that sometimes we love. We did some of that, and we also did some things where we did separate—maybe kept the drums in a separate room, had the sounds and instruments more isolated. Sometimes it’s beneficial if I want to get a really good acoustic bass sound. We even did things where we put a microphone on my Hofner bass. It’s an electric bass, but we didn’t plug it in. We just literally miked the instrument itself and gave it a big fat acoustic sound.

It’s loud enough to do that? You didn’t run a direct line as well?

Chris: If you put the mic in the right place and turn it up loud, yeah, it’s a hollow instrument, so it can do that. When we did that, we had the Hofner going through … I believe it was a flip-top Ampeg B-18, but it was in a different room, so if we wanted to hear only the microphone on the bass, it was enough. It sounded huge, actually, when you turned it up. It was a really amazing sound.

Oliver: For acoustic guitar and acoustic bass, we really like just the mics on there. I suppose there might have been a song or two where we also took a DI from the bass or maybe one of the guitars. A lot of the guitars that I recorded with don’t even have pickups in them. Some of the studio guitars, like an old National—or I have an old ’30s Gibson L-00 guitar that’s just beautiful … none of those have pickups. We love the sound of Chris’ bass. His tone that’s in his hands and his old 100-year-old bass sound amazing. Putting a good mic or two on there, you can’t beat it.

Onstage at Los Angeles’ famed the Troubadour, Oliver Wood goes for a radical bend on his mid-’60s Guild T-100D—a hollowbody with DeArmond pickups that he describes as “a poor man’s Gibson.” Photo by Debi Del Grande

You have a lot of guitars you don’t take on the road, but onstage you often use a Guild.

Oliver: The Guild electric that I have been playing for about 30 years now is a T-100D. A lot of people call it a Slim Jim. It’s a thin hollowbody guitar and it has two little DeArmond cheapo pickups. It’s like a poor man’s Gibson. It’s mid-’60s. I got it back in the ’90s when everybody had a Strat, including me, and I thought, “Everybody’s playing a Strat. I’ve got to find something that nobody’s playing.” That’s the only reason I picked it, but I ended up falling in love with it. It has a Tune-o-matic bridge, which, of course, is not original. I added good tuners and the pickguard fell off long ago. I used to stuff underwear and washcloths in there so it wouldn’t feed back, but I use pretty small amps now, so I don’t really have that trouble anymore. It feeds back just enough.

You’ll find the sweet spot on stage if you need feedback?

Oliver: Exactly. I’m in love with that guitar—that guitar and the amp I have been playing since the beginning of the Wood Brothers. I’ve been playing a little four-watt Kay 703, these $200-on-eBay amps that are basically made of plywood. They have a 6" speaker and you would have bought them at Sears or a department store back in the ’60s. It fits in the overhead compartment of a plane. I’ve been playing that Guild through that little amp since the beginning of the Wood Brothers, and it’s become a signature tone that I feel is my thing. We have a bunch of them. They need work every once in a while. They’re pretty flimsy, but they are remarkably durable and they keep sounding cool. Now I do add a small Fender amp to it, so I have two amps onstage. I have either a Princeton or a Blues Junior or something: a 1x12 or a 1x10 amp right next to the little Kay. We run those together and the sound man favors one or the other based on what song we’re playing.

Guitars

Guild T-100D “Slim Jim”

1953 Gibson CF-100

National Tricone resonator

Modded Stella acoustic

Harmony Bobkat

Amps

Kay 703

Fender Blues Junior

Effects

Keeley Katana Clean Boost

EarthQuaker Speaker Cranker

Radial splitter

Strings and Picks

DR .011–.050 sets (electric)

DR medium sets (acoustic)

Glass slides

Dunlop Purple Tortex 1.14 mm

Basses

Hofner 500/1

Fender Jazz

1920s G.A. Pfretzschner upright

Amps

Ashdown ABM 600 EVO IV

Ashdown ABM-410H cab

Assorted Ampegs

Effects

Mooer Trelicopter tremolo

Strings and Picks

Fender nickel-plated roundwound (.045–.105)

Dunlop Yellow Tortex triangle .73 mm

Chris: That Kay was originally a guitar amp I owned. When we started the Wood Brothers, and we were just a traveling duo, for a long time Oliver would either play acoustic guitar and the electric guitar through that tiny little Kay amp, and I wouldn’t have any rig. I would have just a mic and DI going into the system. We got by for a long time that way, even when we became a trio. I remember playing the Greek Theater in L.A. with the Kay and nothing else for the electric guitar, and it is just four watts. That was always a signature of our sound—a little bit lo-fi and junky—and that Kay really defined it. But the upright bass is a different beast and benefits from more of a hi-fi approach. These days, live, I have an Ashdown amplifier. The whole point of having an amp onstage is to help my stage sound for me, not necessarily for the audience. I tend to get a lot of the tones out of the amp that are good for intonation, good for clarity, and a DI can be mixed with that.

Oliver, your tone tends to lean towards grit and buzz, even when you’re using an acoustic.

Oliver: I have a National guitar, a Tricone, that doesn’t have a pickup or anything, but it’s a dirty sounding guitar. It’s like something is rattling in a way that sounds like distortion, and it is not unpleasant, at least to me, but it’s by no means a pure, pristine sound. It’s messy and I definitely like that. I like that on the electric side, too. I like using small amplifiers with not a lot of headroom.

A good example of that is the guitar tone on “Don’t Think About My Death” from the new album.

Oliver: On that song, I’m playing an old Harmony Bobkat guitar, which has little gold-foil pickups. If I am not mistaken, I am going through some little Epiphone tube amp. It might not be obvious, but that’s also Chris playing his Hofner with a pick, also through a dirty amp. You’re hearing the bass guitar as well, and that’s part of the nasty guitar business that’s going on in that song.

Chris: For a bunch of those recordings, I was using the Hofner going through an old Bassman. I don’t know if people officially think of that as a bass amp or guitar amp, but it sounds great with the Hofner. “Don’t Think About My Death,” for example, has that setup. For some of the song, I’m playing a real guitar-like riff, high up on the neck, and there is a lot of counterpoint with the guitar. But for some of the song, I overdubbed a P-bass, just to thicken it.

When you’re on the road, do you go to pawn shops or guitar stores looking for stuff?

Chris: I used to do that a lot. But I haven’t done it much these days, because I feel like I’ve collected enough stuff, and I don’t have enough time to mess around with the stuff I have, so I feel silly about acquiring more. I’d rather experiment with what I’ve got—set things up differently to get different sounds.

Oliver: If I have time and I find a spot, I’ve been known to put a few things on the bus every once in a while. A newish one for me that I would love to brag about is a ’30s Stella parlor guitar. I sent it to Reuben Cox [of the Old Style Guitar Shop] in L.A. He has this thing he does. He puts an old pickup in the soundhole—I have a Teisco pickup that’s nice and quiet—and then flatwound strings and a rubber bridge. What this does is basically make a guitar with no sustain. Normally, that’s not what we’re going for. We guitar players want it to ring and sustain forever. This is different. It’s a whole revelation in leaving space. When you make a statement on the guitar, it happens, and then it just goes away. It leaves a lot of space for other stuff. The guitar riffs on “Alabaster” were recorded with that guitar. On “Little Bit Sweet,” I’m fingerpicking on that guitar, and, again, I plug it in to a little dirty amp, but it has a dark and sustainless sound. It is unique after playing guitars that ring on forever. It’s cool to have a guitar that’s just dead.

Do you use any different tunings?

Oliver: I play almost entirely in standard. We do a lot of slide guitar songs, and I use what I call a half-G tuning, because I just tune my 1st string down to a D, and that’s all I do. It’s a good way to almost be in open-G tuning, but by compensating a little bit, you can still play most of your chords. You also come up with new, weird chords. You can play a cool seventh chord easy, just because of that one string being changed.

Did you play together when you were growing up?

Oliver: We sure did. I am four yours older …

Although he also plays a Hofner 500/1 and a Fender Jazz bass, Chris Wood is best known for wielding this 1920s G.A. Pfretzschner upright in both the Wood Brothers and Medeski Martin & Wood. Photo by Debi Del Grande

You’re the cool older brother.

Oliver: I am the cool older brother. I started on bass. I gave it to him and switched to guitar, and he just, of course, made history on it. But there were a couple of years there where we were both proficient enough, and into it enough, to jam together. We had a 4-track and we used to jam in the garage. We’d make little weird recordings, then we went our separate ways for about 15 years before we started the Wood Brothers.

Chris: Oliver went to California, and then ended up in Atlanta, and had a band called King Johnson for a long time. I ended up in New York City and started Medeski Martin & Wood. It really wasn’t until 15 years later that our two bands ended up on a double bill. He sat in with us and it became clear that we both had the same job, and there was natural chemistry immediately. That’s what gave us the idea to try to make some music together.

Is this your main gig now?

Chris: Yeah. It is very full time.

What about Medeski Martin & Wood?

Chris: We don’t really tour any more. Occasionally we’ll do some festivals or one-offs. We actually just had a documentary come out. I don’t know how much distribution it is going to get. It just showed at the Woodstock Film Festival. There’s a record we’re trying to finish up from the making of that documentary, which was filmed a couple of years ago.

Oliver: This is our full-time thing. We all do other stuff on the side a little bit—studio stuff, or Chris plays with MMW once in a while still. But no, this is a full-time effort. Between this and family home life, I am toast.

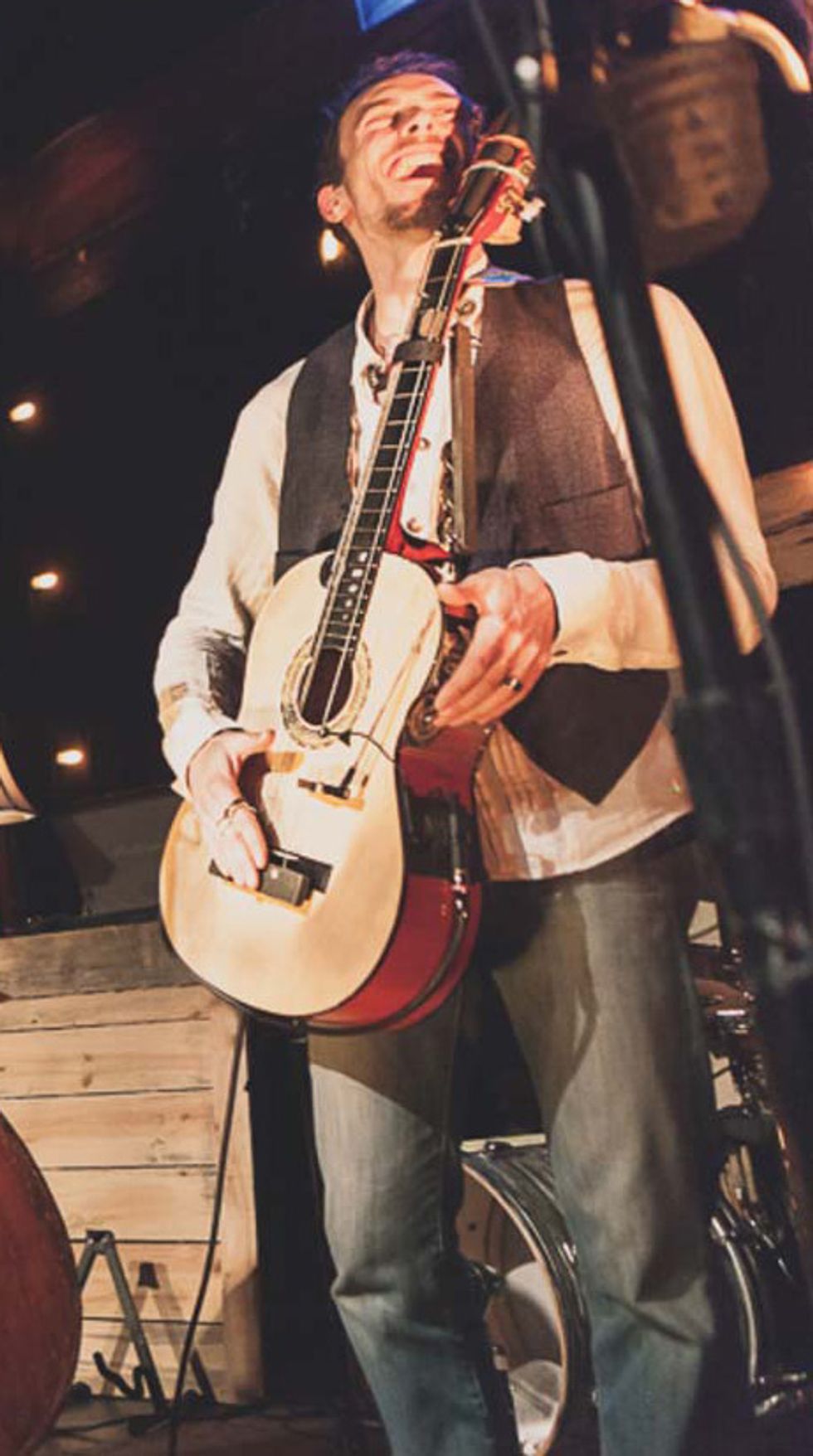

At this 2019 performance to benefit Chattanooga, Tennessee’s Songbirds Foundation, Oliver Wood plays his vintage National Tricone and Chris Wood plucks his 100-year-old 1920s G.A. Pfretzschner bass, while Jano Rix provides a close-up look of the shuitar at work.

The modified guitar in drummer Jano Rix’s hands, at right, is the shuitar, an old 6-string reframed as a percussion instrument that can yield a solid note or two, but sounds more like a mini drum kit. Photo by Debi Del Grande

Meet the Shuitar

When the Wood Brothers play live, their drummer, Jano Rix, will come out front and play an instrument that looks like a guitar. But it’s not. It’s a shuitar—a guitar-based percussion instrument.“The shuitar is an invention of Matt Glassmeyer, a friend of ours in Nashville,” Chris Wood says. “But it co-evolved somewhat with Jano, our drummer. He helped develop it. It’s basically a crappy acoustic guitar—crappy ones sound better for the percussion side of things—and it is converted in a way that the strings are loosened and gathered together. When you hit those, the closest thing you can compare that to is a hi-hat sound. You hit the side to get a sort of snare sound. You hit the bridge to get more of a bass drum sound. There are other little bells and whistles attached to add other sonics, too. It’s a percussion instrument, but it’s a very Americana-sounding instrument. Unlike a djembe, or a shekere, or something that’s borrowed from another culture, the shuitar is meant to sound like a type of drum kit. It’s meant to sound American in that way.”

The shuitar’s function is percussive, despite its appearance and harmonic potential. “Jano can fret a string, bend it, and pluck it like you would a guitar string,” Wood adds. “But it’s loosened to the point that it becomes low and floppy, and it’s mainly used as a metallic percussion sound. But he can, although it’s more for a sonic effect, add a note to the harmony of the song.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)