German lutherie has a 400-year history—and more connections to the United States than you might think. The best way to dive into this legacy is to visit Germany's “Music Corner" region. The three small main cities of Markneukirchen (aka “the music town"), Erlbach, and Klingenthal are known collectively as “Musicon Valley." This musical hub lies in a southern region of Saxony known as the Vogtland, nestled in the mountains at the Czech border, near Bavaria and Thuringia. It's a quiet, rural area, its stunning landscape dominated by lush forests and wide-open meadows full of cows.

For 40 years the region was part of the German Democratic Republic—the former East Germany. Decades of GDR policies have left their mark on downtown Markneukirchen, yet there are remnants of the town's former glory as one of Germany's richest cities. Breathtaking mansions display the sophisticated charm of the past. There's classic German architecture on every corner, and a town center with its mandatory beautiful church and placid cobbled streets. Nearly every building displays a sign indicating that musical instruments are built within. If you're a guitar nut or history nut (or both!), it's hard not to fall for this area's seductive charms.

My wife and I drove down to Markneukirchen for a two-week hiking holiday, which quickly morphed into a hike through the history of Germany's musical instrument industry. Here's what we found along the way.

The Golden Age

Farmers first settled the Markneukirchen area in the 11th century. In the 17th century, Protestants fleeing religious persecution in neighboring Bavaria settled here as well. These refugees included 12 violinmakers from the Graslica area. In 1677 they established a violinmakers' guild, which still survives as the world's oldest. Markneukirchen developed quickly, and by its golden age (1850-1880), 80 percent of the world's musical instruments were made in the region. The area was home to more than a thousand luthiers during the GDR era, and today approximately 130 companies make instruments and accessories here, including all orchestral instruments other than pianos.

When a group of violinmakers begins making instruments, it's only natural for other companies to build on that economy, settling down nearby to make strings, bows, chin rests, and the like. These companies required resources such as sheep gut for strings and lumber mills to cut wood. Eventually an entire marketing/export business emerged to handle the enormous output of instruments. By 1893 a U.S. consular office was established here to handle overseas exports.

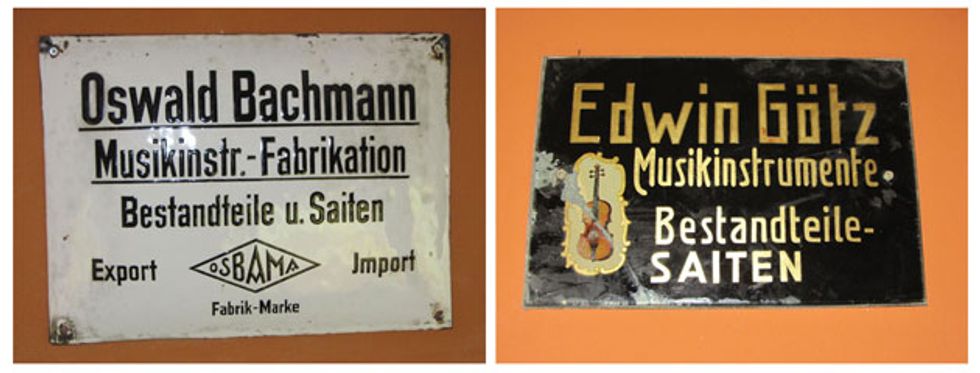

Nearly every building in Markneukirchen's town center displays a sign announcing that musical instruments are built there. Many of these signs are historic. Photos by Dirk Wacker.

Significantly, the separation between building instruments and trading them started early, resulting in a highly effective economic structure. Trading agencies bought instruments in large quantities directly from builders and shipped them worldwide. Of course, traders made a lot of money—much more than the builders. Most of the superb mansions in Markneukirchen were built by trading agency owners. A prime example is the superb Villa Merz, a mansion near the Framus Museum that now houses a lutherie school, part of the University of Applied Science Zwickau. The mansion was built for Curt Merz, owner of a very successful trading agency.

Instrument makers usually worked independently in small workshops, often in their homes. Farmers would build instruments during the long, hard winters, when there was no work to do in the fields. Trading agencies would market these instruments under their own labels, with the actual builders remaining anonymous. Most of the instruments were exported to the United States, India, Brazil, Japan, and Australia. Example: the Andreas Morelli violins common in the United States. G.A. Pfretzschner, an important trading house founded in 1834, bought instruments from throughout the music-corner area and shipped them to his trading partner in the States. The U.S. partner thought an Italian name would boost sales, so they came up with the fantasy Morelli name. This was standard business practice, and instruments of all kinds are still made this way in Markneukirchen. Today you can see the original interior of the Pretzschner trading agency in Markneukirchen's Musical Instrument Museum. In its heyday, Markneukirchen numbered 21 millionaires among its 12,000 inhabitants, and hundreds of people worked in the instrument industry.

The GDR Era

But an 1890 economic crisis, two World Wars, the Great Depression, and the autarchy politics of the Third Reich caused a drastic decline in sales and employment. After WWII the music corner was dominated by communism and its ideals of abolishing personal property. Mass production played an important role as Markneukirchen businesses were reorganized into collectives. Small- and medium-sized companies were merged into craftsmen´s cooperatives and nationally owned companies.

Thankfully, the state didn't completely neglect the musical instrument industry—the East German regime appreciated the quality and value of these instruments. A government-run trading agency imposed annual production rates that instrument makers were required to meet. Compromising situations occurred when materials grew scarce and workers had to improvise. This knack for making something out of nothing is now known as “the Art of the East." Wood substitution is one example: If they ran out of rosewood or ebony, builders used locally sourced pear wood, staining it dark and using it for bridges and fretboards. It proved to be a fine substitute with rosewood-like qualities.

Finished instruments were given to the state agency in return for fixed wages, and then exported for hard currency, even to so-called “class enemy countries" like the United States and former West Germany. The profits bolstered East Germany's ramshackle national budget. Naturally, only the best instruments were chosen for export, leaving only lower quality instruments within the country. (Still, many excellently crafted instruments of that era found their way back to the eastern part of Germany, and some guitars have become quite collectible.)

At its peak, the Musima factory had as many as 1,200 employees who produced up to 360 guitars per day, as well as recorders, violins, zithers, and other instruments. Interestingly, many employees continued to work from their homes or small workshops, even though they were exclusively affiliated with nationally owned companies.

After the Wall

When the GDR was abolished in 1990, large companies were denationalized. Some, like Musima, did not survive. Some workers grabbed the bull by the horns, went into business for themselves, and continue to work as successful luthiers. Karl-Heinz Neudel is one such builder. Neudel is usually overbooked with repair and modification work for vintage German archtop guitars, and he also builds guitars under his own label.

Mass instrument production no longer exists in Markneukirchen—today the Far East dominates that field. But historic companies still handcraft fine instruments—the Gropp family, for example, who are world-renowned for their fine acoustic guitars.

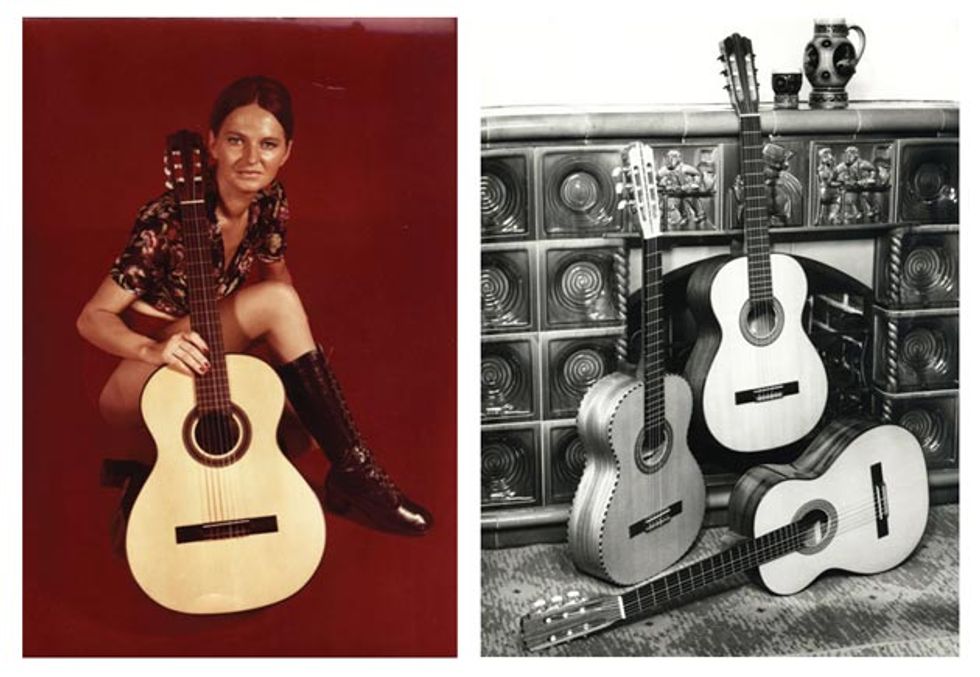

Left: An old advertisement for Musima guitars. Right: A few examples of Musima acoustic models. Photos courtesy of Karl-Heinz Neudel

The Guitars

Despite all the guitars that have been made in Markneukirchen, it's not a town full of music shops or vintage stores—most guitars are purchased directly from the builders. Most current guitars are high-quality acoustic instruments, both classical and steel-string, such as those from Armin and Mario Gropp (www.gropp-gitarren.de), a typical father-and-son workshop in Breitenfeld. They build classical guitars and historical instruments of utmost craftsmanship in the spirit of Richard Jacob and his Weissgerber guitars.

In recent years the industrially made Musima and Sinfonia instruments of the GDR era have become collectible because of their history and charm. Not all of these are great instruments—many are from budget and student lines—but some are fantastic-sounding, great-looking guitars. (GDR-era Sinfonias and Musimas are among my best-sounding guitars.)

Sinfonia Acoustic Guitars

Sinfonia instruments were built from 1961 through 1984. Instruments from 1961 to 1972 sport “PGH Sinfonia" labels, while post-1972 instruments have “VEB Sinfonia Markneukirchen" labels. In 1984 Sinfonia became a part of Musima.

Sinfonia instruments were usually made by anonymous builders in their homes. While some models look simple, with unremarkable decoration, they often use tone woods that were unusual for their time. (I would never part with my 1962 Sinfonia classical, with its cherry back, sides, and neck, spruce top, and rosewood fretboard, all finished in spirit lacquer.)

The old Musima buildings still exist, but they aren't a pretty sight. After the factory closed in the early '90s, the city of Markneukirchen bought the ruins with the intention of demolishing them, but sold them to the Harmona company, who wanted to move their accordion production from Klingenthal to Markneukirchen. They haven't decided whether to restore the old buildings or tear them down to build a new factory, so the Musima buildings lie silent. You can only view them from the outside, but here are exclusive interior photographs of the abandoned factory.

Musima Guitars

Musima's most admired guitars are their archtops, which have a great reputation among players. Musima began building them in the mid 1950s, using original Roger parts out of Wenzel Rossmeisl's workshop. (Rossmeisl's property was seized after the GDR government jailed him for supposed trading crimes.) From there, they developed their own models: Record, Spezial, Solist, Primus, and the export models Ambassador and Atlas. Musima also made cheap archtops, though you can identify higher-quality models by their “German carve" solid tops, a typical Roger feature to which Rossmeisl held a patent. (A German carve top is flat near the edges where it meets sides, but slopes upward closer to its center.) These guitars were available with and without pickups (sometimes discretely embedded in the end of the fretboard), and in both fully hollow and semi-acoustic models. Well-known Musima builders include Armin Weller and Karl-Heinz Neudel, who made most of the high-end and custom instruments during the GDR era.

A real insider's tip is the Musima Nashville steel-string line, designed and built by Neudel. Some custom shop models were built by a single master luthier who used only the best available woods and added fancy embellishments.

Musima also built a Strat-style guitar called Lead Star. Nicknamed “the Strat of the East," it was a fairly faithful Fender copy, but with GDR-produced parts such as a brass inertia block. These are sought-after instruments because of their quality and retro look. Other Musima electric models include the Elektrina, Elgita, Elektra, Etherna, Deluxe, plus some radical metal guitar designs and several bass guitar models.

There were many other gifted luthiers during this era. For more info, visit the Musical Instrument Museum Markneukirchen's online forum. (It's in German, but English postings are common and welcome.)

Markneukirchen is a special place with a quaint and charming atmosphere. Guitar fans might squeeze a visit into their European holiday plans, right between the Black Forest and Oktoberfest. If you have the opportunity to visit the music corner, don't miss these must-see attractions!

Points of Interest:

Musical Instrument Museum Markneukirchen

The Musical Instrument Museum in Markneukirchen, Germany, houses more than 3,000 instruments, including many eccentric stringed instruments built in the region centuries ago.

Founded in 1883, the museum is now housed in a gorgeous 1784 building called Paulus Schlössel. Its collection boasts more than 3,100 musical instruments from all over the world. Curator Heidrun Eichler's role an authority on Markneukirchen instruments is reflected in the collection she's assembled.

The beautiful Musical Instrument Museum in Markneurkirchen is housed in this 1784 building.

It includes the world's largest tuba and accordion, as well as an historic trading station in its original state. Guitar and bass highlights include a 300-year-old double bass and early guitars from Stauffer, Antonio Torres, Richard Jacob (Weissgerber), Martin, and many gorgeous and eccentric Markneukirchen guitars.

www.museum-markneukirchen.de (English version available.)

Framus Instrument Museum Markneukirchen

Opened in 2007, the Framus museum is located near the lutherie school in a building called Villa Brehmer that was completely reconstructed after standing empty for a decade. Rainfall and vacancy damaged the building, but Hans-Peter Wilfer, founder and owner of the Warwick company, bought it and established the museum. Wilfer is the son of Fred Wilfer, founder and owner of the Framus, which produced guitars from 1946 through the company's 1970s bankruptcy. (Some models were reissued in 1995 under the Warwick umbrella.) Framus was Europe's biggest guitar company in the 1960s. The museum displays over 200 instruments from the Framus era, including guitars, basses, banjos, lap steels, pedal steels, amps, and accessories. Museum director Andreas Egelkraut is a walking encyclopedia for all things Framus.

www.framus-vintage.de (English version available.)

Warwick factory and custom shop

Hans-Peter Wilfer was just 24 in 1982 when he founded Warwick in former Western Germany. In 1995, after German reunification, he relocated the company's headquarters to Markneukirchen. The futuristic Warwick quarters are located in town's industrial zone, just a stone's throw from the former Musima building. Its lobby features a large showroom of Warwick and Framus guitars and basses. The facility relies on solar and wind power and is 100 percent carbon-neutral. The Big Kahunas of the factory tour are the custom shop wood supply, the ultra-modern, fully automatic fretting machine, and of course, the paint department.

I met Wilfer in his office to chat about his family's history and connections to Markneukirchen. Wilfer has fond childhood memories of the Framus factory and was 16 when it closed, but he happily started his own bass company. Wilfer chose Markneukirchen as his place of business because of its affordable living and industrial zone, but he also has family ties to the area. “My father was born and raised right across the Czech border in Schönbach [present-day Luby]," Wilfer shares. “I live directly in Markneukirchen with my family and I really like to live here. My kids were born here and they're real Markneukirchen natives—it's a good and joyful place to live and work."

www.warwick.de (English version available)

Luthiers of Interest:

Richard Jacob (Weissgerber)

Weissgerber founder Richard Jacob (1877-1960) is one of Markneukirchen's brightest lutherie stars. After learning to build zithers, he started making guitars in 1899, qualifying as a master luthier in 1905. In 1921 he officially trademarked the Weissgerber name and built approximately 3,700 guitars under this label, the last ones reportedly in the year of his death. After he passed away, his son Martin Jacob took over the workshop and built guitars under the Weissgerber label, many with parts his father had created but never finished. Martin Jacob's death in 1991 marked the end of the Weissgerber era. These guitars are highly collectible today, especially in the Japanese market. Weissgerber guitars were often experimental, using uncommon woods, double tops, and radical bracing patterns. Richard Jacobs' widow, left the original workshop to the University of Leipzig when she died in 1989. For more information, the recently released book Weissgerber by Christof Hanusch details this luthier's entire history (christofhanusch.com)

www.richardjacob-weissgerber.de (German language only.)

www.studia-instrumentorum.de/MUSEUM/weissgerber_inhalt.htm (German language only.)

Wenzel Rossmeisl (Roger Guitars)

Wenzel Rossmeisl, Roger Rossmeisl's father, opened a Markneukirchen workshop in 1948 as a branch supporting the company's Berlin headquarters. The shop produced everything in Markneukirchen, down to individual parts. Wenzel Rossmeisl employed five luthiers. One, master luthier Dieter Hense, is alive and well at 84, though he doesn't build guitars anymore. I had the pleasure to speaking with him about Roger Guitars, and his memory is stunning.

“Wenzel Rossmeisl was not often in the shop," recalls Hense. “He was usually on the road to bring the guitars to the Berlin headquarters, or trying to source and trade needed materials for the shop. I never saw him build a single guitar or part in all those years—this was all up to us. Some of us worked in the shop, while others worked from their homes, making the famous German carve tops or other parts."

In 1951, Wenzel Rossmeisl was arrested at the Leipzig Trade Fair and jailed four years for offenses against the foreign exchange law. His property was seized—all parts, pre-finished bodies, necks, tools, etc.—along with the possessions of two other dispossessed companies. These assets were appropriated for the Musima company, which opened one year later. Only 10 guitars and two small suitcases of Rossmeisl's personal belongings from were saved from the show booth. Because the seized parts were used for early Musima models, you can find complete Roger guitars, minus the brand's logo. Collectors refer to these instruments as “stolen Rogers."

https://schlaggitarren.de/archtop/roger-guitars (English version)

www.vintageguitar.com/1939/rossmeisl-guitars (English version)

https://jazzgitarren.k-server.org/roger.html (English version)

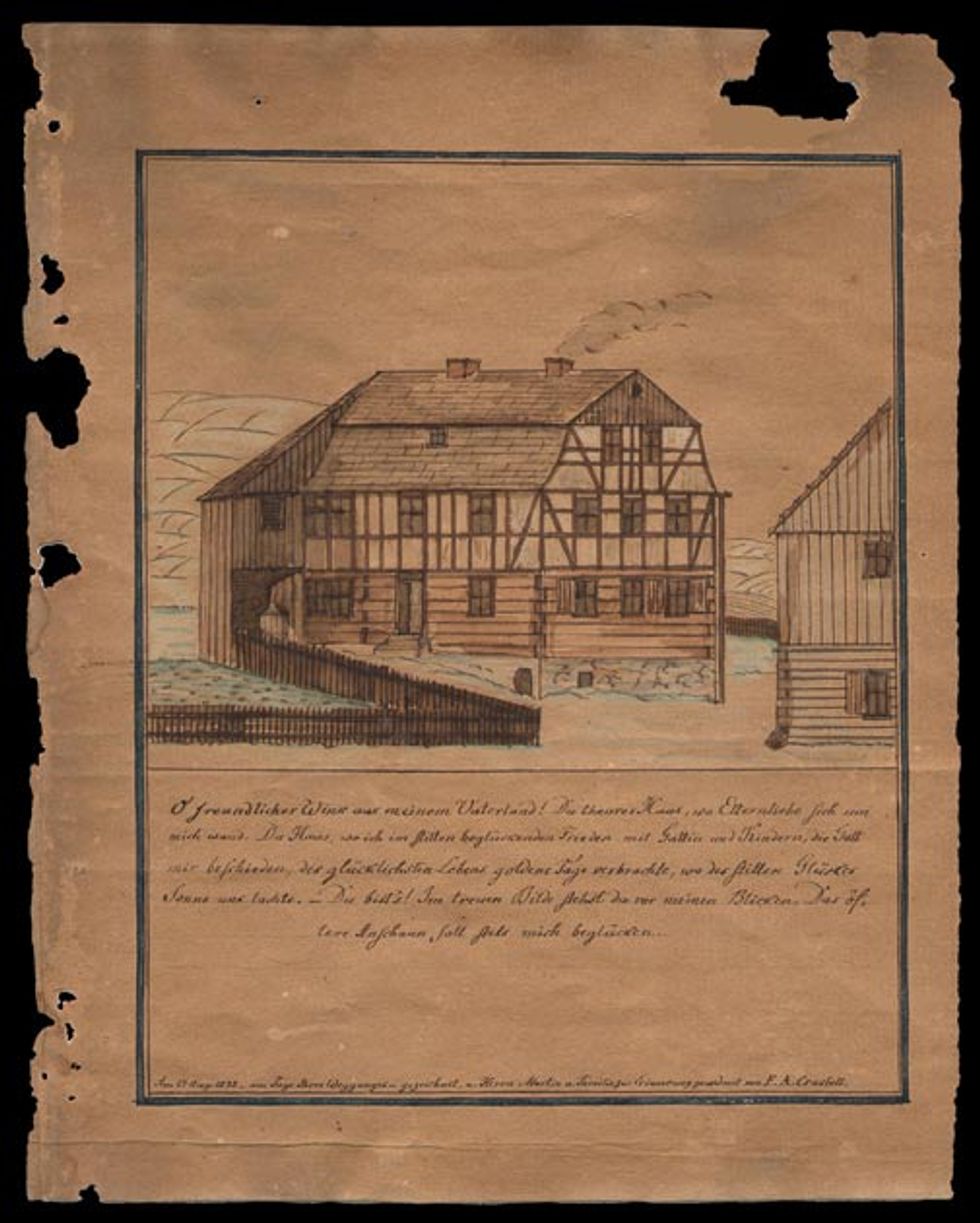

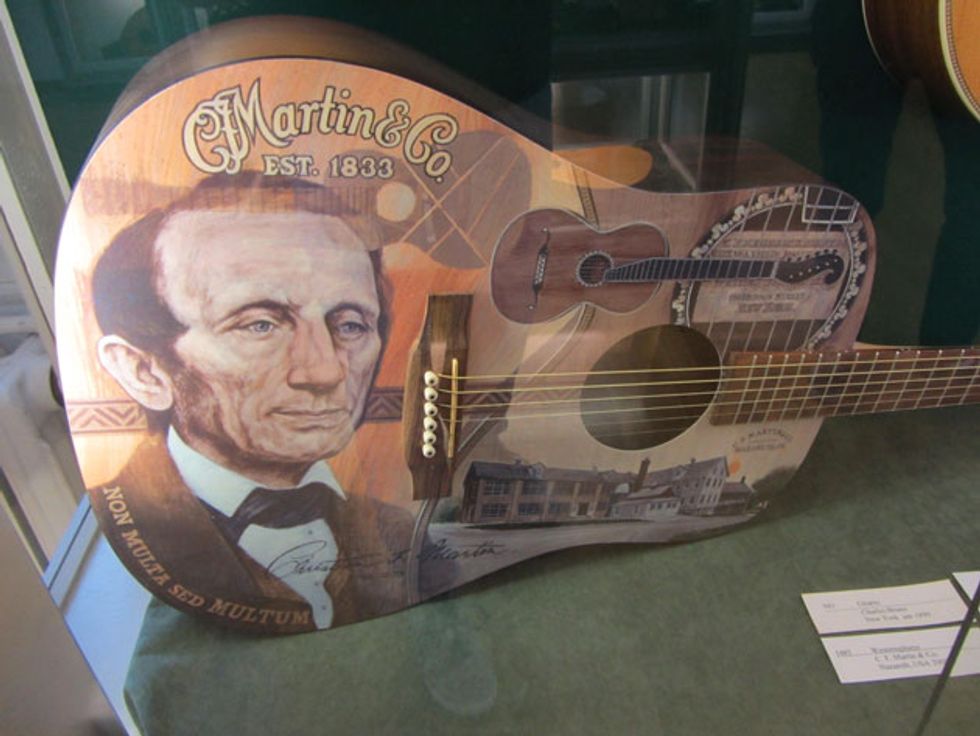

Christian Friedrich ("Frederick") Martin ("Martin Guitars")

After extensive research, Heidrun Eichler and historian Dr. Enrico Weller located the Markneukirchen site where C.F. Martin was born on January 31st, 1796. It was a difficult search, because most of Markneukirchen burned down in a disastrous 1840 fire, and many records were lost. The original house perished in 1840, and a modern house occupies its site near the town center. Markneukirchen plans to erect a plaque here, honoring the town's most famous native son.

C.F. Martin (1796-1873), founder of the Marin Guitar company, is Markneukirchen's most famous luthier. He was born in Markneukirchen on January, 31, 1796, and was building guitars by age 15, just like his father, Johann Georg Martin. At age 24 he went to Vienna to work for Johann Georg Stauffer, one of the most respected luthiers of the day. Talented young C.F worked his way up to a position as Stauffer's foreman. His married a Viennese girl and left Stauffer to work for his father-in-law, who was also building instruments. After a son was born in 1825, the family returned to Markneukirchen, where C.F. opened his own workshop—until emigrating to the U.S. in 1833 at age 37. He settled in New York City—and the rest, as they say, is history!