When the term “baritone guitar” comes up, it’s often met with either indifference or “Oh, that’s the guitar from the Clint Eastwood spaghetti Westerns.” But the baritone electric is a unique, quirky instrument that can go where regular guitars can’t. Let’s take a brief look at it and discuss several of its uses in music production.

The all-knowing Wikipedia describes the baritone guitar as “a variation of the standard guitar with a longer scale length that allows it to be tuned to a lower range.” The Wiki sages go on to tell us that the baritone first appeared in classical music and that Danelectro was the first to introduce the electric baritone in the late 1950s. They also proclaim that the baritone was not originally popular with players or listeners. Ha! Thanks, Wikipedia—I like that last part!

I like to think of the baritone as a cross between a 6-string guitar and a 4-string bass. A baritone has both growling lows and shimmering highs, and it uses very thick strings. For example, the D’Addario Baritone Nickel Round Wound XL set I use on my Fender Jaguar Baritone Custom is gauged .014, .018, .026, .044, .056, and .068. Baritones are often tuned a perfect fourth lower than standard: B–E–A–D–F#–B (low to high). Two other popular tunings are A–A (A–D–G–C–E–A) and C–C (C–F–Bb–Eb–G–C).

Besides Fender and Danelectro, other companies have produced baritones over the years, including Jerry Jones, Ibanez, Schecter, Gretsch, and Music Man. These manufacturers still have baritones in production, as do Eastwood, ESP, and Taylor. You can find other models—including Danelectro’s cool Doubleneck Baritone/6- String—on the used market.

Scale length varies on different instruments, but as a reference, my Jaguar has a 28.5" scale, and the Jerry Jones JJ Original Single- Cutaway measures 28". Gibson made a Les Paul Studio baritone for two years, and it has a 28" scale, as well.

Made popular by the Band’s Rick Danko, the Fender Bass VI is often referred to as a baritone guitar. Jack Bruce briefly played one during Cream’s early days. The Bass VI has a 30.3" scale, which puts it in the realm of a short-scale bass, and it’s often tuned an octave below standard guitar.

Yes, Duane Eddy played a baritone on the Peter Gunn theme and in Westerns and surf music in the ’60s, but that was just the beginning. The Cure made great use of the baritone in the ’80s, and then, in the ’90s, guitarists got heavy with it. Bands such as System of a Down, Type O Negative, and Dream Theater have featured them, too. Mike Mushok of Staind had a signature Ibanez model, but he now plays a signature PRS with a 27.7" scale. His string gauges run from .014–.068.

My producer/engineer friend D. James Goodwin (the Bravery, Norah Jones, Devo) turned me on to the baritone. He currently uses two models, a reissue of the above-mentioned Fender Bass VI and a Jerry Jones. “I put a Tele-like fixed bridge on my Bass VI,” Goodwin notes, “to avoid the tuning issues you get with the tremolo. This makes it much more stable. It’s heavy and feels old, which I love. The Jerry Jones definitely sounds more hollow and not as thick as the Fender. It also responds to effects in an odd way, which is likely due to the pickups. It’s a cool bari, but I use it mostly for texture or something out of the ordinary.”

Goodwin tunes his baritones differently. “My Jerry Jones is tuned G–C–F–B%–D%–G. I tune my Fender Bass VI to E–E, an octave below standard. The Fender has a really rubbery quality when you tune it that low, and it sounds amazing. Complete Duane Eddy tone! I use it a lot to double bass parts. It can thicken a bass track without making it muddier. For instance, I’ll double the bass with fuzzed-out baritone in a chorus or a bridge of a song, just to give it some extra guts. It makes things feel more powerful. But sometimes it just becomes a chordal texture—I’ll play chords, maybe down an octave from a guitar, just to create an interesting, wide texture.”

But the baritone is not just for the bottom of a mix. “I sometimes use it as a lead instrument, played up high,” Goodwin continues. “The timbre becomes dark and very unexpected, which is a nice twist in a common guitar solo.”

Both Goodwin and I have also replaced the stock pickups in our Fenders with Curtis Novak models, which are reasonably priced and drop right into either a Jaguar or Bass VI. While Novak doesn’t make a specific “baritone” pickup, he’ll custom-wind them to your specs.

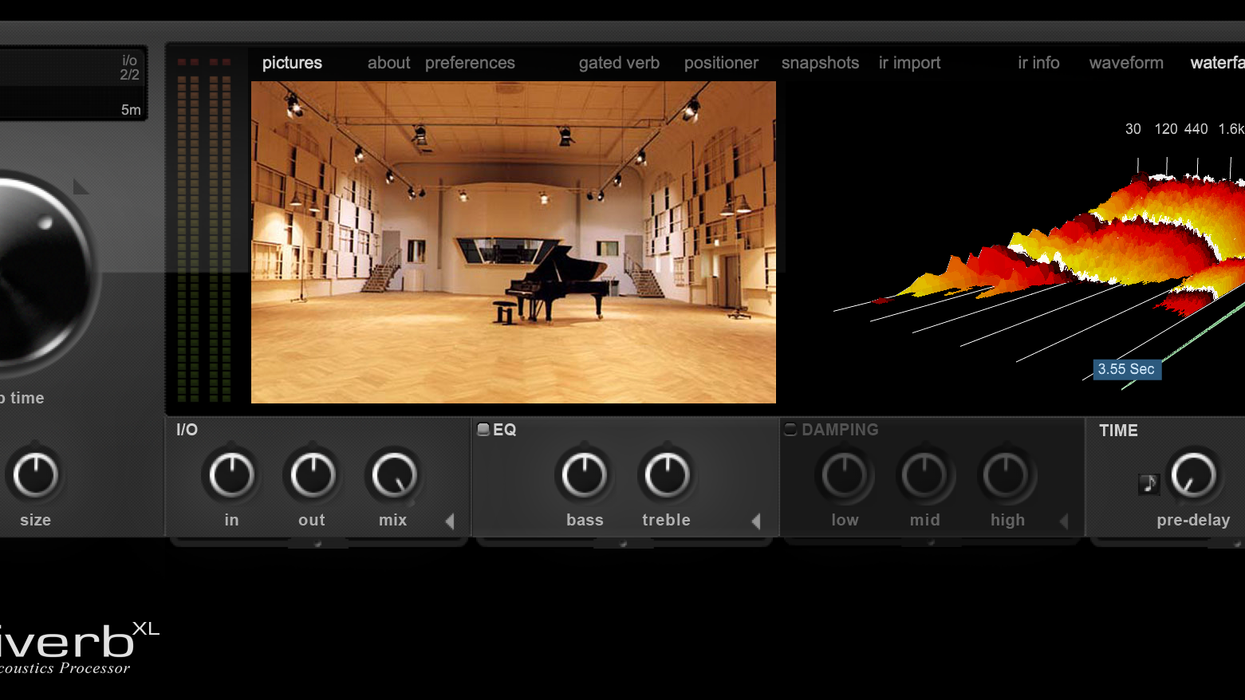

I use my baritone in several different ways, as well. It can handle thumping low-end bass parts and super thin, nasally high parts. It sounds great with effects, and I often rely on my standard SoundToys EchoBoy delay and Eventide H3000 Harmonizer presets to create a wide, dimensional sound field. My bari Jag sounds killer plugged into my old Gibson and Magnatone amps with some ’verb and vibrato.

For those of you who watch Pawn Stars on the History Channel, you can hear my distorted baritone during each episode. It’s on one of the bumpers where the program goes to the quiz, and it sometimes appears on cues throughout the show. Sounds kind of like a bass, but kind of not.

Baritone guitars are a different animal. They’re sometimes odd to play due to their tunings, the necks can bend because of the increased string tension, and all the switches on my Jaguar drive me crazy. But plug one in and hit a chord, and you’ll say “Damn, that’s cool!”

[Updated 2/7/22]