You never know quite what you’re going to get when Brian Setzer comes out with a new album. Sure, you can bank on stellar guitar playing and the unmistakable tones of his iconic ’59 Gretsch 6120, 6G6-B Fender Bassman, and Roland Space Echo. But otherwise it’s a bit of a toss-up: Other than big, ’50s-style hair and an orange hollowbody, Setzer’s main trademark is his restless musical ambition and a penchant for styles that sometimes seem at odds. Remember—although he’s the guy who spearheaded the early-’80s rockabilly revival with Stray Cats hits like “Rock This Town” and “Stray Cat Strut”—he’s also the guy who sprinkled it all with punk, blues, New Wave, swing-jazz, Southern rock, country, and bluegrass seasonings. And that was well before he embarked on an even more ambitious solo career.

You could easily argue that Setzer’s voracious appetite for musical adventure and growth is what keeps him relevant—it’s the reason his repertoire feels like it’s in constant bloom. But it’s also been a bit of a thorn in his side. For starters, it had to be hellacious for the Massapequa, New York, native to figure out what to do after the rockabilly revival lost its mainstream steam in the mid to late ’80s—the only guitarists who seemed to get attention were those who resorted to hair metal or, during the first half of the ’90s, grunge. Consequently, Setzer’s genre jumping in post-Cats years gave the impression he was frantically searching for a new, bankable identity. Solo efforts at Byrds-y 12-string Rickenbacker jangle mixed with drum machines were executed well enough, but the die was already cast: People knew him as “the Gretsch guy.” Yet that sonic signature was too nostalgically narrow—and his skills and expertise too wide—for him to have kept selling millions of records.

Add to that the fact that Setzer has never resorted to flavor-of-the-moment gear tricks: He eschews pedals, and though he picks up a baritone or banjo here and there (or maybe tries an esoteric vintage amp for a song or three), it’s pretty much just vintage Gretsch, Fender, and Roland. That means his guitar sound can seem stuck in time—albeit gloriously so to us fans.

But by the end of the Clinton administration, Setzer caught lightning in a bottle again. He not only made his teenage dream of fronting a 17-piece big band a reality, he also rejuvenated his career as the de facto ambassador of the late-’90s swing revival—with a rockabilly rave-up edge. Never one to sit and stew, Setzer has since put out albums of authentic early rockabilly, modern-ish rock ’n’ roll with a Texas-boogie feel, traditional jazz instrumentals, classical-inspired big band, and film noir stuff, with the occasional nod to gospel and doo-wop thrown in for good measure.

But with Rockabilly Riot! All Original, his first album since 2011’s Setzer Goes Instru-Mental, the Twin Cities Pomp is back to what put him on the map in the first place. All Original is chock-full of the twangin’ slapback and thumping slap bass that Setzer fans tend to love most. As always there are twists, including rabblerousing piano work courtesy of Kevin McKendree on many tracks, but the difference between the diversity of Setzer’s Stray Cats and early solo efforts—or even something as recent as his 2006 solo album, 13—is that of late he seems to have truly mastered the art of seamlessly incorporating all these stylistic nods into the classic Setzer sound. Rather than feel like boredom-induced hopscotching, the cheeky Western vibe of “Calamity Jane”—which features funky clavinet, bouncy saloon-style piano, and a whimsical circus organ—comes across as classic Setzer having a hoot of a time in a cowboy hat. And the high-lonesome pedal-steel sighs on “The Girl with the Blues in Her Eyes” (played by session ace Paul Franklin) combine with a breathily intimate vocal performance and a gorgeously simple progression to produce one of Setzer’s most beautiful and memorable songs since “Stray Cat Strut.”

We recently spoke to Setzer about the making of All Original—including how his daughter’s love of classic rock helped summon his “songbird” muse—and why he’s never tempted away from his go-to gear.

YouTube It

Setzer's first single off Rockabilly Riot! Volume One, "Let's Shake."

It’s been nine years since you released Rockabilly Riot! Volume One, the old-school covers album. Tell us how things unfolded this time around.

Well, first you have to start with a spark—I always say that the songbird has to come visit me, y’know? My daughter, who lives in Nashville, was listening to her iPod and she had the “peas” in her ears. I said, “Let me hear those.” I pulled them out of her ears and thought it sounded like crap. She goes, “You just don’t like the band!” I said no, that’s not it. Then I asked her what she liked. She said, “I like Zeppelin.” I pulled out an old Zeppelin vinyl record and put on “Immigrant Song.” I have an old 1963 McIntosh tube stereo with studio monitors, and I blasted it. She went, “Oh my god!” So for Christmas, her mom bought her a stereo. She and her friends hunt down vinyl. That’s the deal. She’s got the first Clash album on vinyl. If I find something, I’ll send it to her … the first Ramones record—she likes that kind of ’80s punk and classic stuff, as well as new stuff. I thought, “How cool! Wow, I did something that my daughter thought was cool!” That’s what got me going with the line, “She plays vinyl records...” then that riff came up. I go, “That’s really catchy and simple!” That’s the hardest thing to come up with—catchy and simple. That’s what gets the ball rolling. Okay, I’ve got the riff, I’ve got the idea for the song—now let’s go.

So “Vinyl Records” was the first song?

That was the first song I wrote for the record, yeah. After I’d written two or three songs, I thought, “This is a rockabilly record, no doubt about it!”

“Calamity Jane” has a familiar sound, but it’s a bit of a new vibe for you, too. There’s that funky clavinet part and sort of a whimsical circus-organ-type thing mixed in with the upright piano.

You actually listened to the record. Thank you!That’s production—that’s Peter Collins’ ear there. My idea for that song was—of course, it starts out rockabilly—but then there’s that lyric. I thought, “‘Calamity Jane’—no one’s written a song called ‘Calamity Jane.’ There’s no band that calls themselves Calamity Jane.” At least no one that I knew of. I thought it was a really great title. I pictured an old Western, an old saloon where they’re playing poker and the piano player’s playing. Peter Collins thought about putting in a clavinet to make it bounce. I thought when I wrote the song that the vocal line would pull it into something else, like almost a bluegrass thing. It’s kind of a mix of genres, I guess.The circus organ was Peter’s idea. He said that he heard, like, a calliope. He had this crazy thing in there, and it sounds like the man on the flying trapeze.

In your head you can almost see a monkey running around collecting change….

Yeah, it fit perfectly what I was trying to do. It gave it that saloon vibe, like an episode of Gunsmoke where the gunfight breaks out.

On “What’s Her Name,” there’s a swampy vibrato sound on the guitar. Is that from a Magnatone amp?

That is a Magnatone amp. I wanted vibrato, and I had this old Magnatone sitting there—like a late-’50s, Buddy Holly Magnatone. I don’t use effects, except for the Roland Space Echo for the slap, so I wanted a good vibrato. I didn’t bother with pedals. It just sounded so good. I set it up in the corner and plugged into that thing. That’s the only change in amps I used—just the Magnatone for that one song.

Brian Setzer's Gear

Guitars

1959 Gretsch 6120

1956 Martin D-28

Amps

1963 Fender Bassman head

’60s Fender 2x12 cab

Effects

Roland Space Echo

Strings and Picks

Strings and Picks

D'Addario EXL110 electric sets

D'Addario EJ15 and EJ17 acoustic sets

Fender medium picks

Custom Belden cables

Do you remember which model?

I have it right here, let’s see … it’s a beauty, I’ll tell you that. It says Custom 280, high fidelity. So a Magnatone 280? I don’t know much about them, except that I bought it years ago, and it’s just been sitting here. I ought to use the damn thing.

While we’re on the subject, you’ve always been quite adventurous with genres, but with gear you’ve pretty much been faithful to your Gretsch hollowbodies, your Bassman, and your Space Echo. Do you experiment much on the side with other gear just for the hell of it? So many guitarists are pedal junkies—are you at all interested in that stuff?

Here’s the thing: I’ve tried all the pedals and stuff, but to me, for my playing—I’m not knocking people who use pedals, that’s fine—but it turns into bells and whistles. “Hey listen—my guitar sounds like a machine gun!” It gets very old, very quickly for me. I understand the use for different styles of music. It just doesn’t fit my style. It becomes very kitschy. Plus, it’s just in the friggin’ way. A pedalboard would just be a pain in the neck to have in front of me. I’ve tried different things. I had a couple of pedals once, and I can tell you one thing—you can take a Gretsch with any crappy overdrive pedal and make it sound like a Les Paul through a Marshall. But you can’t get a Gibson to sound like that Gretsch. It doesn’t. I’ve got a ’59 Les Paul—and I’m keeping it to trade in so that my girls can go to college—but I can’t get any music out of that. I understand that other people can. But I can make the Gretsch sound like that Les Paul. Not the other way around.

On the other end of the guitar spectrum, you seem to be able to get as much twang and snap and presence out of your Gretsch as a lot of players get out of a Tele. What’s the secret?

Teles are a whole different animal. The Gretsch, to me, is halfway between a Gibson and a Fender. You can get both, but it has its own unique tone with those Filter’Tron pickups. I haven’t been able to beat it. I think the 6120 is the best guitar ever made. It’s got to be that hollowbody box. I can get any sound out of a hollowbody guitar. I don’t know why. Even the new ones. I mean, they just play so well. If you can get a ’59 6120 that actually works and plays in tune—you’ll have to do a lot of work on it—that is the ultimate beast for me. It’s not beatable. Like I said, I’ve got some old shit laying around. I’ve got a ’56 Strat and a ’59 Les Paul, and they do not touch a 6120.

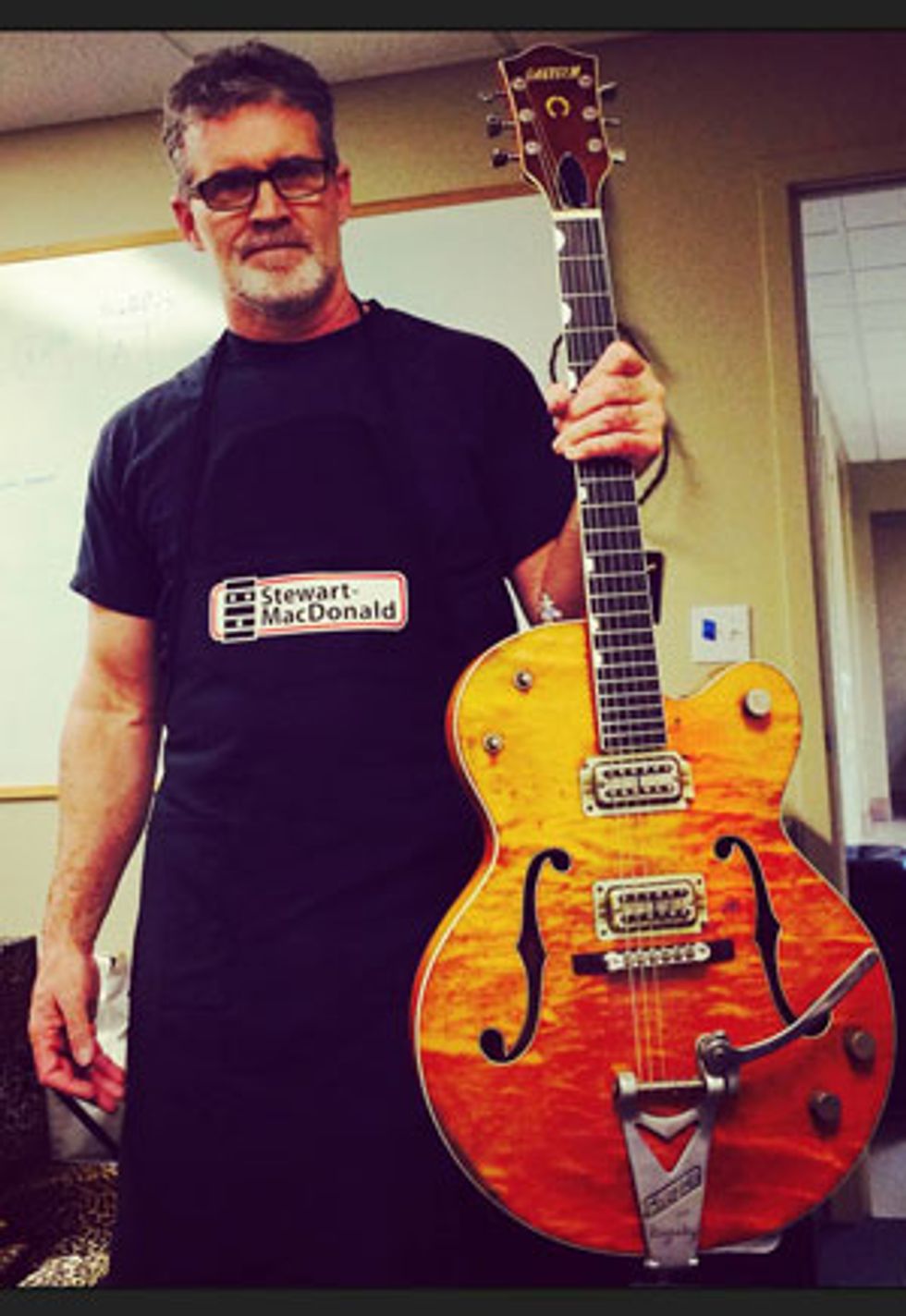

Tom Jones working on one of Setzer's 6120s.

Tom Jones on Setzer’s Signature TV Jones Pickups

TV Jones mastermind Tom Jones—who’s been rehabilitating old pickups and winding new ones for Brian Setzer for 20+ years—explains the process behind the Stray Cat’s new signature pickups.

“It’s my job to ensure that all of Brian’s guitars play and sound the absolute best they can possibly be,” says Jones, who debuted the pickups at the March 2014 Musikmesse gear show in Frankfurt, Germany. “A few years back, I found that a few of Brian’s new Hot Rod signature guitars—which were sent to me by Gretsch to set up for his upcoming tours—sounded slightly brighter acoustically. So I decided to design a new pickup to bring out the best in these guitars—higher fidelity on top, with a slight punch in the bottom end—by using sonically unmatched coils and custom steel-alloy pole screws. The results were beyond my expectations.”

Speaking of Filter’Tron-style pickups, you’ve kind of been the poster child for TV Jones Classics for a long time. Can you talk about your new signature pickups?

Tom [Jones] is really the guy responsible for it. I don’t know what I’m looking at when I pull those things out! I might as well be looking at a part that goes into a tractor. Unbeknownst to me, Tom was swapping out pickups in my guitars—especially with the [Gretsch Brian Setzer signature] Hot Rod models. It’s kind of hard to tell in the heat of the moment—each stage sounds different—but I picked up the guitar and thought it sounded different. I could hear the fingerpicking a little better. I’d go, “Has Tom been doing something to my guitars recently? These pickups sound fantastic on any stage.” Tom said that he’d been swapping them in and out without telling me [see sidebar]. Don’t ask me what he does, because he’s kind of like a mad scientist, but I said, “Whatever you’re doing, these are the ones we have to keep.” I seem to be able to get more distinct when I fingerpick, and I’m getting more bottom end. The top is not as shrilly. It’s not as muddy, yet they’re still ballsy. Gosh—I sound like a wine connoisseur [laughs].That’s the best way I can describe them. They’re a little different. The Classics still rock, though—they’re still a great pickup.

Did you use any other unusual gear for the album?

I came off the road from the Christmas tour, and the ’63 Bassman was perfect. The Space Echo didn’t break. The Gretsch was broken in—just playing like nobody’s business. I was like, “Don’t fix it! I don’t want the frets polished or the tubes changed. I just want to set it up and play.” I find that, as much as I want to experiment and change—like using an old tape echo or a single-coil guitar—I always go back to that same setup. It’s just my sound. When it’s all working right, it’s magic.

So was it the original ’59 Gretsch from your Stray Cats days?

I’ve got a ’59 that I’ve been using for probably 20 years. It’s from the same year, maybe the same batch. I rarely take the Stray Cats one out. It got stolen for two years, so it’s been through the mill. So I’ve got that ’59, and I just recently got a new one that’s hot shit—it sounds amazing! According to Jay Scott’s book [Gretsch: The Guitars of the Fred Gretsch Company], it would be a 1960 model year, and it sounds incredible. I know Tom had to re-magnetize the pickup because they were a little weak, but whatever he did, it’ll be tough to beat. I just got it and used it in Japan and—oh my god! But some of them have it, some of them don’t. Even if it’s made in 1959, it doesn’t mean it’s going to be a great guitar.

Otherwise, was it pretty much the usual setup—the Space Echo, Bassman with the 2x12, and the ’59?

Yeah man, that’s what I play.

What about acoustics?

I just got a ’56 Martin D-28. That’s my go-to—it’s a cannon.

Let’s get back to the album. “The Girl with the Blues in Her Eyes” is so laid-back with that Western shuffle and the lonesome steel guitar, yet it’s really beautiful. Your vocal delivery is particularly touching in that one. How did that song come about?

Well, thank you. There’s always this songbird that comes—I can’t wait for him to come again. Usually [on a song like that], I’ll start on a D and go to a G or something. But I went from a D to a Dm.

Yeah—I love how that minor chord is the key to the whole song.

Right? I went, “Ohhh, I haven’t heard that.” When you’re given that little gift, you have to finish it. I did the same with G to Gm—“Oh my gosh, there’s a song!” It happened like that. I wanted the lyrics to be touching, but not sappy. My friend Mike Himmelstein—I really respect his lyric writing—he gave me the song back, and it was great, but it wasn’t called “The Girl with the Blues in Her Eyes.” That was just in the lyrics. I said, “Oh no, Mike, there’s our title.” Rewrite it, and that’s the title. He only had to change a few things, and then he came back with the lyrics. I knew when he did that we’d got it.

Were you interested in singing when you first started playing guitar, or did you do it out of necessity?

No, I didn’t want to sing. I never wanted to be the singer. I wanted to be the guy standing in front of the amp so that I could let someone else have the spotlight. I wanted to fiddle with the amp and the knobs on the echo thing. I never wanted to do it, but we could never find a singer. I said, “Okay, I’ll do it.” I don’t think I’m a great singer, but there was nobody around any better.

That’s pretty inspiring because, although you’re heralded most for your guitar and instrumental prowess, you’re a master of multiple vocal-delivery techniques. For example, the tight, perfectly harmonized background vocals on “Let’s Shake” and “Stiletto Cool” are as effective as anything else in giving those tracks that old-school vibe.

Well thanks. I’m lucky that I can hear those chords. If I have to do doubles, like the background vocals on “The Girl with the Blues in Her Eyes,” I can hear those harmonies. And I can change with the next chord. I think that comes from just knowing the guitar. And I love the way Eddie Cochran and Joe Strummer sing as much as I do Elvis and Nat King Cole. They’re two totally different styles of singing, so I guess you have to take what God gave you.

YouTube It

Hear Brian Setzer let loose with the new tune “Nothing Is a Sure Thing” in this May 2014 performance from Nagoya, Japan.

What advice would you give guitarists who are forced into the vocal spotlight like you were?

Well, first of all, it doesn’t matter what style you’re playing. You have to follow your heart. You’ve gotta do what you want to do—unless you’re in a cover band that’s making a steady paycheck where you’re playing a bit of everything. I realize that, because I used to do that. I can’t stress enough how learning to read and write music has made me the player that I am. I know that it’s hard, and I sound like a teacher at school, but if you learn how to read and write music, it connects the dots. It can show you how to play through a chord passage, how to connect those two chords, how to get out of that pentatonic scale. I hear blues guys just doing that constantly. There are so many ways to make yourself unique. I don’t care if you’re playing heavy metal—if you learn how to read and write music, it connects the dots and it makes you one hundred times the player you were without reading and writing. It just does. Everything makes sense to you.

You’ve mentioned the songbird thing a couple of times. That’s one of the toughest things for musicians, coming up with songs that really stick—that are worth something. How do you know when the songbird is really there and that it’s not just some throwaway thing coming to you?

Well, that happens, but you’ve got to see it through. Sometimes I start with things that I don’t know are that great. But I would say that you have to see it through. Finish it up. It might be the one. If it were easy, we’d have a thousand Rolling Stones around. It’s hard. But that’s the whole deal. It takes a long time. Don’t be anxious about it. Just let it come, let it happen. Once you get the first thing going, once that songbird visits, things usually snowball.