Guitar players love making messes. Slathering on too much fuzz at inopportune times, peaking VU meters, and rendering separation useless in the studio. It goes with the territory. True, sometimes you need complete isolation or the pristine precision of a Steely Dan record, but more often than not, there's something special about getting gross with your guitar.

But that's just aesthetics.

Unfortunately, guitarists also generate a lot of physical waste. Old strings, picks, batteries, and tubes need to be disposed of. Blown speakers, frayed wires, trashed amps, unwanted enclosures, and fried electronics need to be discarded as well. For better or worse, modern music making generates a small mountain of unwanted junk.

But don't fret—pun intended—these are solvable problems. Options and innovations abound.

In this modest dissertation, we focus on three areas: recycling waste, innovative repurposing of discarded materials, and—at what first glance might seem like a side point—sustainable harvesting of wood.

Part I talks about garbage. Some things, like guitar strings and metal amp chassis, are easy to recycle and might even have marketable value. But others, like old tubes and single-use batteries, raise difficult questions and could be too much trouble—or just too expensive—to recycle.

Part II profiles two innovative businesses—Wallace Detroit Guitars and Analog Outfitters—that do incredible things while repurposing old materials. Each company, in its own manner, has found a way to turn trash into treasure.

Part III is about wood. Most guitars are made of wood and many of those woods are rare and expensive. But two of those woods, rosewood and ebony, are becoming scarce. That scarcity has raised enough alarm that CITES—the international body that deals with such matters—has imposed new, strict regulations. But it isn't as bleak as it sounds. We focus our attention on the important initiatives being made to develop a more sustainable model for both the growing and harvesting of these precious tonewoods.

"Above all, don't put metal in your trash." —Christopher Bosso, professor of public policy at Northeastern University

In this story, we speak with entrepreneurs, captains of industry, tenured professors, and other experts to give you an overview of these complex and sometimes complicated issues. There's a lot more to say, but consider this a thorough introduction. Ultimately, guitar players make messes, but for the most part, those messes—at least the non-musical ones—can be cleaned up.

Part I: Responsible Junk Disposal

Broken strings, worn out picks, dead batteries, fried circuits, non-functioning gear, stripped cables, and blown tubes—what should you do with all that junk?

Strings

Electric guitar strings are made from different types of metal and that's true for most acoustic guitar strings, too (with the obvious exception of nylon). Those metals include steel, nickel, cobalt, bronze, and various other alloys.

But guitar strings don't last forever. They wear out, break, or get crusty and gross, and at some point, you must change them. Most players change their strings on a regular basis. Many pros change them every gig.

What should you do with your old strings? Should you throw them in the trash?

"Anything with metal in it should be recycled," Christopher Bosso, a professor of public policy at Northeastern University says. "It has material value and local recycling programs actually give money for that."

D'Addario recently made string recycling easier for guitar players, with their Playback program, which allows players to drop off unwanted strings at more than 400 music retail spots around the U.S., including all Guitar Center locations. As an incentive, those who join the program earn points for recycling that can be used toward new strings or gear.

Through the Playback string recycling program, D'Addario and partner TerraCycle have recycled over 1.2 million strings in 2017. A reported 1.5 million pounds of strings are accumulated in landfills each year.

You can also take matters into your own hands. Ben Juday, the founder of Analog Outfitters, a company that builds amplifiers from repurposed Hammond organs, recommends having special bins for metal waste. "I have a couple of 5-gallon pails in my garage," he says. "Any scrap or bit of wire, brass or copper, or any little bit—anything from guitar strings to cans to little pieces of steel—I put in there and either put it out for the scrappers or take it to the scrapyard."

Scrapyards pay for junk metal, melt it down, and resell it. But don't expect to get rich recycling strings. "You would have to have a heck of a lot," Bosso says. "Scrapyards deal with significant amounts. Obviously, there's an aggregator. Cities and towns that do that place big magnets over their recyclables and anything that's metal gets pulled to a separate place. It's then sold by the ton or gets separated into the different types of metals, depending on where it is in the waste stream. More recyclables than we care to admit don't actually end up being recycled. But anything that has metal in it is of value in the marketplace. The real trick is, how do you get that into the right stream? If you put your strings into a recycling container or where the collection bin is, that's better than tossing it into the trash. Above all, don't put metal in your trash."

Batteries

Most effects pedals used to run on batteries, though the industry trend seems to be moving away from that. "I've probably sold close to 1,000 pedals and I've only had two people ask about batteries," Eric Junge, the owner of Hungry Robot Pedals, told us in an earlier interview ("Stompbox Savants," September 2016"). "I think the general consensus is, most people aren't using batteries anymore," he added. "A lot of my designs are very tight internally—I couldn't even fit a battery into a couple of them. So my take is, 'Am I going to make this pedal bigger for the 0.1 percent of the public that's going to use a battery?'"

That said, some players still rely on batteries and they are recyclable, although most communities are not set up to handle them. "In an ideal world, you would take these single-use batteries and figure out a way to recycle them," Bosso says. "But hardly any states have recycling programs for single-use batteries. Car batteries do have a very high recycle rate. That's because they contain a valuable metal, lead, and they're big, and most times they are replaced by professionals at repair shops. You have a collection process, market value, and there is actually a process to extract the metal and other stuff from the batteries. There is a very high rate of recycling for car batteries as contrasted to consumer batteries."

In 1996, legislation was passed to phase out the use of mercury in batteries, making it legal in most states to dispose of single-use alkaline batteries via the regular trash. But single-use batteries can still be recycled at local recycling centers, along with rechargeable batteries and other electronic waste, which are restricted from being tossed in with regular trash.

Destroyed Amps, Fried Circuits, and the Forgotten Gear Graveyard

Anyone who's played long enough—and loud enough—has probably fried their fair share of circuits, amps, and speakers. (For example, I fried the output circuitry on my Peavey Heritage 2x12 combo twice. Smoke billowed from the chassis and everything. The second time was at an audition. I didn't get the gig.) You can leave your old gear in the garage. You can convert it into a lamp or coffee table. Or—believe it or not—you can sell it. Reverb even has a category for non-functioning gear. "Keep in mind," the site claims, "there are still plenty of buyers out there who are in the market for project guitars and other fixer-upper items."

Juday agrees. "I partly got my start by buying broken equipment, fixing it, and reselling it back in my repair days. There are people who want broken gear for a bargain." But if no one wants it, bring the metal parts to the scrapyard. "Take out the speaker and metal chassis and take that to a local scrapyard. They weigh it and pay you for the scrap metal. That metal is chopped up, melted down, and turned into new steel. However, there really isn't a good way to recycle the wooden cabinet. Your best bet is to break it down with a sledgehammer and throw the wooden enclosure away."

Circuit boards and non-functioning electronics are recyclable as well. Your local scrapyard will take them. However, the EPA also lists several retailers—including Staples and Best Buy—that have buy-back and drop-off programs. "If you want to see some interesting videos," Juday says, "search 'circuit board recycling.' You would not believe what they're able to do by grinding them up and melting them down. A circuit board has all kinds of precious metals—like gold and silver—and also harmful metals like lead and cadmium. They can all be recovered through the recycling process."

Tubes, Cables, and Picks

What should you do with blown tubes? Short of converting them into shot glasses, not much. "People say, 'You should recycle them,'" Bosso says. "But the response is, 'Where do I take them? What's going to happen to them?' It's a pain in the ass to do it. Cities and towns will hold the occasional eWaste day. You bring them your eWaste and what happens, frankly, is oftentimes it is put in a big container and shipped off to developing countries where someone might try to get the metals out of it."

"Anything with metal in it should be recycled." —Christopher Bosso, professor of public policy at Northeastern University

Juday agrees. "There's not a good way of recycling tubes, which is unfortunate," he says. "The good news is they don't have very much metal in them. They do have some precious metal in there, like tungsten and other metals, but it's in such small quantities that it's not really worth anything."

Your frayed cables can be disposed of like other metals and the copper wiring can be reused for various projects. Some even claim you can use old braided and shielded cable as solder wick (Visit Instructibles.com for " How to Recycle an Old Dead Cable" article.), but the verdict is out on that.

There's also not much you can do with your old, beaten, worn-out picks. "Some plastics are recyclable," Bosso says. "They have some value in the marketplace because they can be reused. But a lot of plastics increasingly don't have much market value, so cities and towns may end up incinerating it."

However, there is a trend for converting old credit cards, vinyl records, and other hard plastics into picks. If you feel a connection to your last credit card—or maybe if you've paid it off—you can continue using it to make music.

Part II: Making Treasure out of Trash

Wallace Guitars uses reclaimed wood from abandoned Detroit buildings and houses. According to CEO Mark Wallace, old-growth pine dated between 1860 and 1930 yields favorable tonal characteristics.

Wallace Guitars

Wallace Detroit Guitars, based in Detroit, Michigan, builds guitars out of wood salvaged from the city's many abandoned properties. "When you're in Detroit, it's hard not to notice that there are a lot of vacant properties," Mark Wallace, the company's founder and CEO says. "It looks like these places should be torn down, thrown into a dumpster, and nobody should ever think about them. But what's exciting to me is that we're actually finding really incredible wood in those houses and turning that into instruments that stand up next to any handmade instrument."

Most of the wood comes from the Architectural Salvage Warehouse of Detroit, a local non-profit that functions as an unusual lumber yard. "We're not breaking into houses we don't own," Wallace says. "I walk into a warehouse that looks like a scene in Indiana Jones and it's full of reclaimed wood. I can see the wood, I can see the species, and they track which property a piece of wood came out of."

The most plentiful species of wood found in old Detroit houses, other than oak, is old-growth pine. "There are 60,000 vacant properties in Detroit and most of them have pine in the joist. I knew that if I could turn a pine two-by-four into a great guitar, I would have a supply that would last a very long time. I didn't know if it was going to work—so we spent a lot of time prototyping—because pine has different characteristics from swamp ash, maple, or anything you traditionally make a guitar out of. What I discovered, which was really thrilling, is that the pine that comes out of houses that were built between 1860 and 1930 is generally pine that was grown in old-growth forests and it's very different from pine that is grown in modern forests. Typically, if you're trying to produce a two-by-four to sell at Lowe's or Home Depot, you're going to use trees that are spaced out a certain distance to maximize light and rainfall. You're going to hit them full of fertilizers to make them grow straight. You're going to trim them so they don't have any knots in them. In the old forests, every tree is competing with every other tree. They are fighting for sunlight and grow in a context of scarcity of natural resources. The reason that matters is that the growth rings you get from the old growth forests are much tighter than the growth rings you get from a modern forest. What I have is pine, and because it's so damn old, it's much more similar to ash, almost to maple, than pine you would typically expect to see in 2017. I've got this really beautiful stuff that has this really interesting performance characteristic to it."

The bodies are made from bonded-together two-by-fours and come in two styles: long grain and end grain. "The long-grain style is like racing stripes," Wallace says. "If we find trims made out of mahogany or walnut or something, we chop that up, plane it down, and slab it together. In terms of the standard pine, I really like showing off the history of the wood: the stains and the nail holes. [For the end grain], we do a long grain back and that forms the neck pocket. We then do a 5/8" cap on top where we expose the grain."

But working with these woods does pose unique challenges. "The big one is metal. Even if you use a metal detector, you still never know what's buried inside. We burn up a lot more blades than others do. Making sure the wood is dry to a consistent level is really important to us as well. Some of this stuff has been sitting outside for years."

Wallace guitars are constructed piecemeal by different teams of luthiers around Detroit. One group does the glue-ups, one does the planing, another does the sanding and finishing coat. The necks and set-ups are done separately as well, and the necks are made from maple. "I can't find enough consistent maple to do a reclaim," Wallace says. "We use Michigan maple and try to keep it in the state, but they're not reclaimed."

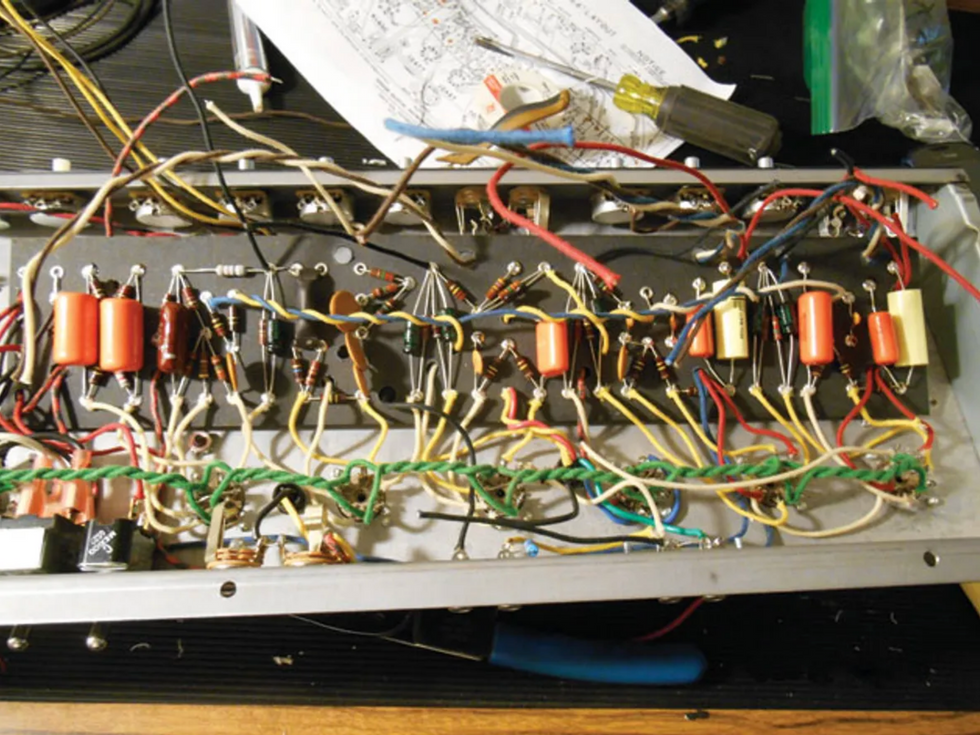

Illinois-based Analog Outfitters builds, or "up-cycles," amplifiers, cabinets, effects, and MIDI controllers out of parts scavenged from old Hammond Organs.

Analog Outfitters

Analog Outfitters, based just north of Champaign, in Rantoul, Illinois, builds amplifiers out of parts scavenged from old Hammond organs. "I started in 2002 as a repair/live sound company and did a lot of work on Hammond organs," Ben Juday, the company's founder says. "People would try to give me these old organs and I took a lot of them. They had no market value—people were just throwing them away—and I started messing around with them. In 2011, we started manufacturing amplifiers and it's continued since then."

Juday only dismantles organs that people don't want—he gets most of them for free—and his biggest expense is hauling them back to his warehouse. "Sometimes people are upset with us for destroying these old instruments," he says. "But you've got to realize, the ones that we destroy literally [would otherwise] end up on the side of the road, in the rain, and in the landfill."

He tries to salvage, or "up-cycle," as he calls it, as much as he can from the organs as well. "We reuse the wood, the copper wiring, the amplifiers, and [even] the tubes whenever we can," he says. "Hammond used redwood, mahogany, walnut, and a lot of really good woods—some of which you can't even get any more. We use these premium woods in our wooden enclosures. We're not able to use all recycled materials, obviously, and I've never actually calculated the percentage, but a high percentage of the materials in our products are repurposed."

"If you saw our warehouse, we probably have about 100 organs that are not disassembled and another 200 that are." —Ben Juday, Analog Outfitters

But Juday is motivated by more than just green considerations; he also thinks old organs, particularly their output transformers, sound great. He says vintage transformers, like vintage pickups, possess a special mojo not usually found in newer gear. "Many vintage transformers have that same magic sound and it has to do with how they were wound," he says. "They used methods that are more expensive to do and today people have taken shortcuts. The thing to remember about a guitar amp—a tube guitar amp—is that the output transformer is the most important part of the whole amp. It's like the transmission in your car. I don't care how good your engine is, if you don't have a way to harness that power with a good transmission, you're not going anywhere. It's the same thing with a guitar amp. The output transformer takes the energy created by that amplifier and couples it to your speaker. If you don't have a good coupling device, you're never going to get the tone that you want."

Building amps from repurposed materials isn't simple or cheap. "It's not like we just flip a few wires," Juday says. It's a painstaking process that involves transporting, dismantling, cataloging, and warehousing the reclaimed materials. "If you saw our warehouse, we probably have about 100 organs that are not disassembled and another 200 that are—the transformers are here, the amp chassis are here, the speakers go over here, the wood is catalogued here, the wiring goes here. It's a pretty involved process." Plus, reworking an existing chassis also involves a lot of metal work, like drilling new holes and stripping away unwanted parts. "It probably takes more labor to do it the way we do, but the best form of recycling is repurposing and we really are repurposing a lot of those old parts."

Here's Analog Outfitters Scanner that was reviewed by PG and is used onstage by Doyle Bramhall II.

Analog Outfitters doesn't just build amps. They make the Scanner, which repurposes the vibrato and reverb units from old Hammond organs. They make a MIDI controller from repurposed keyboards. They use the organ's wood—when they're not using decommissioned street signs—to make speaker cabinets and enclosures. But they can't use everything.

"People try to give us organs from the '70s," Juday says. "We have to say no, because the wood that they used was particle chipboard, which is essentially junk, and the amps were transistor based. So those 1970s organs are of no value to us. We don't have the room to take those and to try to recycle them. But anything from the '50s or '60s, that used real solid wood and vacuum tube components, has value to us."

Part III: Wood

Bob Taylor walks in the Cameroon bush during a visit in 2017. Taylor Guitars—in partnership with Madinter Trade, a Spain-based supplier of tonewoods—recently purchased an ebony mill in Cameroon, an African country on the Gulf of Guinea.

Photo courtesy of Taylor Guitars

In January 2017, CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, which, according to their website, is "an international agreement between governments whose aim is to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival," listed the entire Dalbergia genus—i.e. every species of rosewood—as Appendix II. That means, in a nutshell, that rosewood is considered a species at risk and its international usage is regulated.

Needless to say, that sent the guitar world into a tizzy.

"Basically, what happened is there has been growing demand for rosewood, mainly from China," Eric Meier, the author of WOOD! Identifying and Using Hundreds of Woods Worldwide and the administrator of The Wood Database, says. "I'm not trying to completely blame the Chinese, but they have a growing middle class and a cultural tradition of rosewood furniture. The resurgence in demand for rosewood furniture is an unprecedented amount of global demand, which was the main contributing factor. Obviously, there are other factors as well, but that was the main contributing factor for the CITES decision. CITES controls how and when wood moves across international borders."

However, according to Meier, the regulation does have a provision for touring musicians. "This doesn't affect Brazilian rosewood, which has always been restricted," he says. "But for the other species of rosewood they've put the limit at 10 kilograms (about 22 pounds) and non-commercial. Basically, as long as you're not selling the instrument—it isn't a commercial transaction, you're just traveling with it—then it's exempted."

"One small piece of rosewood on the guitar makes it a CITES-controlled product, forever." —Bob Taylor, Taylor Guitars

That isn't the case if you want to sell a guitar, even if you're selling a used instrument. "It's affected the guitar business in a negative way," Bob Taylor, the founder and CEO of Taylor Guitars, says. "People think that the 'guitar business' is conducted only by corporations. That is a false idea, because guitars are durable and last for a century or more. In that time, those guitars will have many owners. In today's world, individuals sell used guitars all day every day, often across borders. This doesn't happen with flooring, or even most furniture, for example. It's just as illegal for a person with a 20-year-old guitar to sell it across a border without all the proof and paperwork as it is for Taylor Guitars to do so with a new guitar. As the CITES rosewood regulation is currently written, it criminalizes people who have no idea or even the ability to know about the legality of a certain guitar. One small piece of rosewood on the guitar makes it a CITES-controlled product, forever. You can see the problem with this. It's relatively easy for Taylor Guitars to comply because we are a business and we deal in new guitars. We know exactly what pieces of wood are in them, their botanical names, where they came from, and we have the accompanying proof. We also know the management authorities around the world. We have the good fortune of a good reputation. We know how to file the paperwork. It isn't easy, but we can comply. It's very hard for an individual, who is the third owner of a guitar to comply, because he has to know all this, too, and prove it."

The challenge is greater for smaller, boutique builders—especially those who have been in business for a long time. "Most of the sources that we have always gotten wood from—and 'we' means the guitar-building community at large—are places that have done this forever," Amilcar Dohrn-Melendez, the materials buyer for Ryan Guitars, says. "A lot is older material, which is really good for us, and is the stuff that's harder to track. Kevin [Ryan] has been building for 30 years and he has material that is that old. Most shops do. When you get serious about building guitars, a lot of your investment early on is to get those source materials. You can use them forever and the longer they cure, the better. Guitar builders are wired to be like squirrels and keep gathering stuff. But how do you find out who the person you bought it from bought it from if you bought it 10 years ago? You can imagine, if it was longer than 15 or 20 years ago, it's just a wash in terms of how any of us kept track."

"We're married to ebony because it works," says Bob Taylor. "Substitutes don't work as well. Plus, they have their own sustainability problems." This majestic ebony tree resides in a forest in Cameroon, in Central Africa.

Photo courtesy of Taylor Guitars

Ebony is another wood the guitar building community is concerned about, especially since it's one of the best woods to use for fretboards. "As a builder, one of the things I would say about ebony is that structurally it takes frets really well," Dohrn-Melendez says. "The density and how stiff it is—even compared to rosewood—frets just grab on and hold on like you want them to."

"We're married to ebony because it works," Taylor adds. "Substitutes don't work as well. Plus, they have their own sustainability problems. It's good to realize that guitars aren't the only instruments that depend upon ebony. Violins, cellos, contra-basses, also use it. I think it's better to conserve and regrow ebony than to look for alternatives."

Along those lines, Taylor—in partnership with Madinter Trade, a Spain-based supplier of tonewoods—purchased an ebony mill in Cameroon. Learning about woods at their source changed Taylor's opinion about what types of ebony were suitable for use. "When we first arrived, we found out from suppliers that they cut down many trees to find one with a pure black heart. Not all ebony trees are pure black and many trees were simply left to rot. That was not acceptable to us. I thought the wood was beautiful, and I felt I was in a position—not as a supplier of ebony, but as a maker of guitars—to change perception. Today, we are repurposing much of the colored wood into sides and backs. We had to build a lot of capabilities, but it's a great use of that material, and we don't have to depend upon using it solely on fingerboards."

Taylor Guitars is committed to replanting and conserving ebony through the Cameroon Project. The first stage of the project planted 15,000 seedlings in the Crelicam nursery, with the goal of supplying instrument manufacturers with high-quality ebony in the future.

Photo courtesy of Taylor Guitars

Part of the challenge, in terms of sustainability, is that trees take a long time to grow. "Some of the controversy in Madagascar was someone cut down protected trees in the national forest," Meier says. "The trees were 200 or 300 years old. Yes, trees can grow back, but if you just consider that that was a 200-year-old tree—there is an element of timing. Is it realistically going to be sustainable in our lifetime?"

However, in spite of that, Taylor is planting new trees. "We have a huge project to replant ebony and it's in full swing," Taylor says. "In fact, we just signed a public-private partnership with the government of Cameroon on November 14, 2017, at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Bonn, Germany, to cooperate on our initiative. We are partnered with the Congo Basin Institute in Yaoundé, Cameroon, which has UCLA as the driving partner. Professor Tom Smith, the director of the Center for Tropical Research, has spent 35 years working in Cameroon on forest-related science. There is top-notch science being implemented with them as our partner. Together, we are making progress planting ebony as well as fruit and medicine trees in villages, and the villages own these projects. This first stage of the project will plant 15,000 ebony trees. My partner Vidal de Teresa from Madinter Trade in Spain oversees the work."

One thing that isn't possible—at least not on a significant scale—is growing these tropical trees in greenhouses. "What you need is good site location, good soil, and good seeds," Taylor says. "Hawaii is a contender to grow ebony, rosewood, and mahogany. There's a lot of mahogany already on Hawaii, so we know it grows well there. There is also the topic of improving the species through planting shoots from a good tree, thus copying that tree's qualities. With time, we may be able to crossbreed trees as well to make certain varieties that serve us well, just like it's done with edible plants. While we haven't crossbred anything yet, we have grown new trees from cuttings of trees we like."

"The environment that these trees grow in has so much to do with what they become as trees and, then by proxy, how we can use them as builders," Dohrn-Melendez says. "It's a difficult thing to manufacture. For example, you have to have a rainforest if you want to grow Brazilian rosewood. You might not have to go to Brazil, but Nebraska isn't going to cut it."

[Updated 8/10/21]

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)