| |

|

The Voice Box creates two- to four-part harmonies directly from your vocals, and in the same key as your accompaniment instrument. Simply plug your mic into the Voice Box’s mic preamp, plug in your instrument and you’re ready to go. It’s that easy. No setup, no menus to navigate. Studio-quality reverb lets you independently add depth to your dry vocals and harmony vocals. An octave setting will perfectly track your vocals even without an accompaniment instrument. The focused 256-band articulate vocoder, designed by the genius that made the vocoder popular for EMS, features adjustable harmonic enhancement and controllable formant shift. Use any synthesizer and you have the classic vocoder of the seventies and eighties. Plug in your guitar and mic and you have a talk box.

Features include:

• Harmonically matches any electric instrument you plug into it

• Professional quality pitch shifting algorithm produces realistic harmonies

• The Low & High Harmony independently produces two harmony notes: 3rd and 5th

• 9 accessible programmable presets

• Natural Glissando

• Gender Bender knob allows for male/ female formant modification

• Built-In Mic Pre with Phantom Power & Gain Switch

• Balanced XLR Line Output: Interface directly with any mixing board or A/D converter

• US96DC-200BI power supply included

Watch the demo:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/v/Qnj2oU8MYCI&hl=en&rel=0≈=%2526fmt%3D35 expand=1]

Hit page 2 for a more in-depth look at the Voice Box's features & modes...

FEATURES:

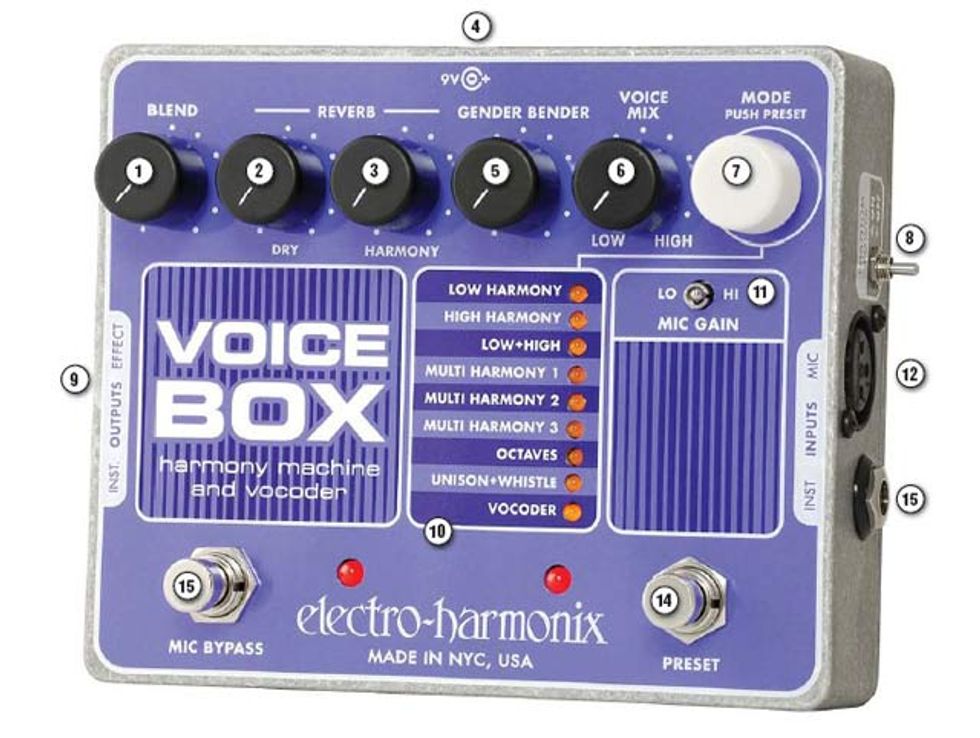

| 1. Blend The Blend knob is a wet/dry control for the effect output jack. The knob ranges from 100% dry (counter clockwise) to 100% wet (clockwise), then blends evenly between the two extremes. | 2. Dry Reverb The Dry Reverb knob is a volume control for the reverb that is applied to the Dry vocals. | 3. Harmony Reverb The Harmony Reverb knob is a volume control for the reverb that is applied to the effected vocals. This reverb can be applied to all effects, including the Whistle effect. |

| 4. 9V Power Jack The Voice Box comes with an AC adaptor, but accepts Boss-style AC adaptors as well. | 5. Gender Bender The Gender Bender knob adjusts the formant shift applied to the harmony, octave or effected voices. This allows for either more femaleor male-sounding voices, depending upon whether the voice is pitch shifted up or down. | 6. Voice Mix The Voice Mix knob mixes between a low harmony voice and high harmony voice. The range of the Voice Mix knob varies based on which mode is selected. |

| 7. Mode The Mode knob scrolls through the Voice Box’s nine modes. It also has a push switch that saves and loads presets. The Voice Box can save one preset per mode. | 8. Phantom Power Toggle Switch The Phantom Power toggle switch supplies +45V to the microphone, and is only for use with a condenser mic. | 9. Effect Output XLR/Instrument Output

1/4” Jacks The vocal harmonies, vocoder and other effects, as well as the dry and bypassed vocals are output from the Effect Output XLR. It can be directly connected to the line input of a mixer, onstage breakout boxes, or the input of an A/D converter. The output impedance of both the XLR and 1/4” is 700 ohm. |

| 10. Modes The Voice Box features nine modes, each holding one preset. See below for a closer look at the modes. | 11. Mic Gain Toggle Switch The Mic Gain toggle switch changes the sensitivity of the mic preamp in the Voice Box. HI gain mode is used in standard applications; LO is useful if there’s clipping, a sensitive mic or a loud singer. | 12. Mic Input XLR Jack The Mic Input XLR jack is a fully balanced microphone input with an input impedance of 10k ohm. |

| 13. Mic Bypass Footswitch/Status LED The Bypass footswitch toggles between effect mode and bypass mode. In bypass mode, the instrument’s signal still passes through a highquality buffer stage between the input and output jacks. | 14. Preset Footswitch/LED The Preset footswitch loads a preset into whatever mode is currently active, or will scroll through each mode’s preset. The Preset LED indicates whether a preset is loaded, and if changes have been made to the preset. | 15. Instrument Input 1/4” Jack The Instrument Input 1/4” jack is a standard input with an impedance of 2.2M ohm. In all modes but two (Octaves and Unison + Whistle), the Voice Box requires an instrument input along with the vocals. |

MODES:

Low Harmony

The Voice Box creates two harmony voices below the note you sing. The low voice is usually the lower 3rd below your note, but will sometimes be the lower 4th, depending on the most appropriate harmony for the chord your instrument plays and the note you sing. The high voice is usually the lower 5th below the note you sing, but will sometimes be the lower 6th, again depending on which harmony is the most appropriate.

High Harmony

The Voice Box creates two harmony voices above the note you sing. The low voice is usually the 3rd above your note, but will sometimes be the 4th, depending on the most appropriate harmony for the chord your instrument plays and the note you sing. The high voice is usually the 5th above the note you sing, but will sometimes be the 6th, again depending on the most appropriate harmony.

Low + High Harmony

The Voice Box creates two harmony voices, one above the note you sing and one below. The low voice is usually the lower 5th below the note you sing; the high voice is usually the upper 3rd above the note you sing.

Multi Harmony 1

Lower 3rd, Lower 5th and Upper 3rd. The Voice Box creates three harmonies: two lower harmonies and one upper harmony. The harmonies consist of the lower 3rd harmony, the lower 5th harmony and the upper 3rd harmony.

Multi Harmony 2

Lower 3rd, Lower 5th, Upper 3rd and Upper Octave. The Voice Box creates the same three harmonies as in Multi Harmony 1 and adds the upper octave. The harmonies consist of the lower 3rd harmony, the lower 5th harmony and the upper 3rd harmony. Added to the mix is the upper octave.

Multi Harmony 3

Lower Octave, Lower 5th, Upper 3rd and Upper 5th. The Voice Box creates three harmonies (one below, two above) plus an octave down. The harmonies consist of the lower 5th harmony, the upper 3rd harmony and the upper 5th harmony. Added to the mix is the lower octave.

Octaves Mode

Octaves mode pitch shifts your vocal up and down exactly one octave. Since the amount of pitch shift is preset to an octave, this mode does not require an instrument to be played along with your vocal.

Unison + Whistle Mode

Unison + Whistle mode is really like having two modes in one. Each function is separate from the other. Unison mode allows for formant shift without changing the pitch of your vocal. For example, you want to sound more female but without changing your pitch. Whistle mode synthesizes a whistle tone exactly two octaves above the note you sing.

Vocoder Mode

Vocoder mode turns the Voice Box into a 256-Band vocoder. Vocoding is an effect that allows a voice to modulate an instrument or sound source. The controls have been optimized so that the vocoder is very much plug, play and sing; the musician does not need to do much work to create fantastic sounding vocoder effects. As with most vocoders, both a vocal signal and an instrument signal are required to obtain the proper effect.

MSRP $286

Street $214.50

MORE:

- Enter to win a Voice Box

- Voice Box Product Page

- Watch the demo: