For all the power of modern processor chips, there’s one thing reverb pedals—and even high-end digital rack units—have trouble nailing, and that’s authentic spring-reverb sounds. Many come close enough to satisfy players who simply want a dash of the springy mojo that’s defined so much electric-guitar work since the 1960s, but the warmth and complexity of a cranked vintage Fender reverb—particularly the swooshiness of three-knob outboard units—remains elusive, even for those with 21st-century digital firepower.

Not being an engineer, I have no idea why it’s so tough to emulate such an antiquated technology. Maybe it’s because other reverb types primarily create the aural illusion of ambient spaces in various “sizes”—a feat that focuses on replicating the original signal at varying intervals and with different EQ shadings. Convincing spring-reverb emulation, on the other hand, must replicate the sonic je ne sais quoi derived from the mechanical process of routing a guitar signal through electrified springs. And of course the hot vacuum tubes driving many iconic reverb units are integral to the sound, too.

Whatever the reasons, getting a pedal to replicate the pleasing, asymmetrical glory of a cranked spring reverb has long been nearly impossible. With certain newer stompboxes you might think you’re getting close, but A/B them with the real deal and you hear a difference—particularly in the smooth roundness of the decays. For surf purists and spring aficionados addicted to that squishy, retro vibe, digital artifacts in the reverb trails is an unacceptable dead giveaway. So if you don’t already have a spring reverb in your amp, how do you get that inimitable sound without having to fork out close to a grand (Fender’s ’63 Reverb reissue goes for $700, and boutique units are even more) for a bulky effect the size of a guitar head?

Recently, three pedal companies tackled this challenge head-on: Mojo Hand Fx unveiled the Dewdrop, Catalinbread brought out the Topanga, and Subdecay debuted its Super Spring Theory. I tested each pedal with a variety of guitars, including an Eastwood Sidejack Baritone with Manlius Jazzmaster-style pickups, a Schecter PT Fastback II B, a Telecaster with Curtis Novak pickups, a Telecaster with Nordstrand NVT A3 pickups, a Danelectro ’56 Baritone, a Schecter Ultra III with a TV Jones Magna’Tron, and an Eastwood Airline H78 reissue. I also enlisted one of the hottest surf guitarist in PG’s home state, Brook Hoover of the Surf Zombies (surfzombies.bandcamp.com), to get his take on how convincing these three contenders sound. Brook used his old Jaguar and Mustang guitars to test each pedal through his collection of vintage and boutique amps, and we A/B’d each with his Fender ’63 reissue outboard reverb, as well as the black- and silverface Deluxe Reverbs he often uses for Surf Zombies work.

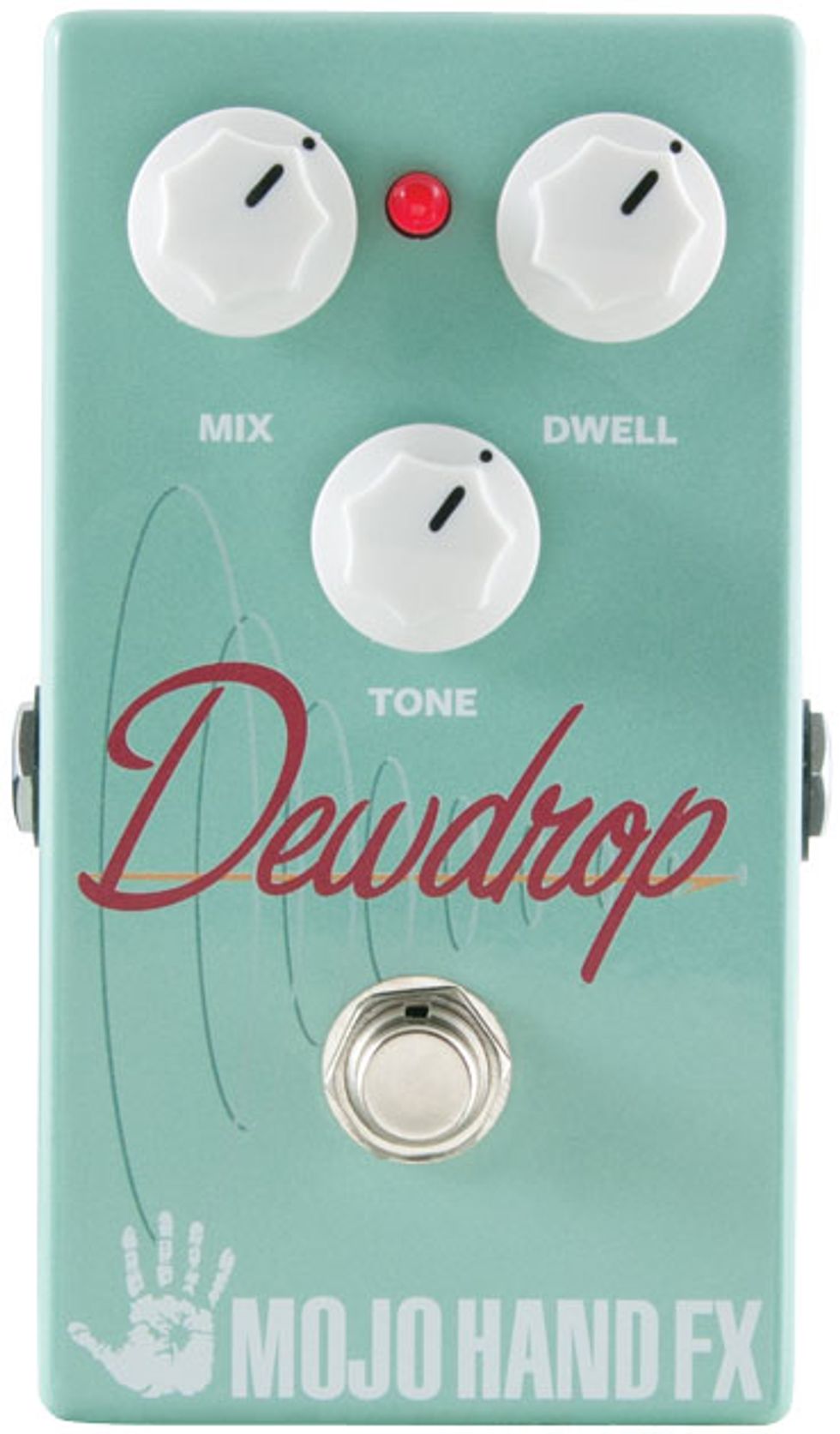

Mojo Hand Fx Dewdrop

Based in Kirbyville, Texas, Mojo Hand Fx has impressed us in the past with their Colossus pedal’s interesting interpretation of the classic Muff sound (November 2011), as well the dimensionality and broad tonal range of Nebula IV phaser (June 2012). Their entry in this roundup, the Dewdrop, is the largest of our would-be spring doppelgangers—it’s about a 1/4" taller and wider than the Subdecay and Catalinbread. It’s also the simplest. Ostensibly, all the pedals here aim to capture voluptuous Fender reverb, but the Dewdrop is the only one that attempts to do so with no more knobs than you’ll find on a three-knob outboard unit. Like an old Fender’s mixer control, the Mojo’s mix knob governs the wet-to-direct signal ratio, while dwell controls the depth/length of the effect, and tone alters the EQ of the reverberations.Ratings

Pros:

Intuitive control setup. Offers off-the-beaten-path pawnshop-’verb vibes for those so inclined.

Cons:

Short, slightly modulated echoes will disappoint traditionalists seeking iconic spring sounds. Dwell and tone knobs have limited range.

Tones:

Ease of Use:

Build/Design:

Value:

Street:

$179

Mojo Hand Fx Dewdrop

mojohandfx.com

The engine driving the Dewdrop is an Accu-Bell BTDR-2H reverb module, one of the various versions of the “Belton brick” processor used in BYOC reverbs, many DIY ’verb kits, and pedals such as Malekko’s Spring Chicken, the JHS Alpine, Lotus Pedal’s Iceverb, and Solid Gold FX’s Surf Rider.

Plugged in, the Dewdrop definitely possesses the mandatory splashiness that players look for in a spring-style ’verb. However, to my ears it sounds more like a series of very short echoes than an archetypal Fender reverb. Brook—who owns a pretty enviable collection of vintage amps—compared it to the ’verb from a solid-state 1960s Kay or Silvertone amp.

Another interesting aspect of the Dewdrop’s tones is the subtle modulation it adds to the decays. It’s certainly a usable sound, but some players will find it perplexing that you can’t dial the chorus-like undercurrent out. Meanwhile, the mix control has adequate range—you can add a hint of splatter or get super splashy—but the potency of the Dewdrop’s dwell and tone controls is quite narrow. There’s variety there, just not as much as most players looking for Fender-style reverb would expect: Moving a knob a notch or two on many other pedals typically alters the associated parameter as much as the Dewdrop’s tone and dwell knobs do throughout their entire throw.

The Verdict

Mojo Hand Fx’s Dewdrop deserves kudos for striving to replicate the simplicity and straightforwardness of old-school reverb units. Players looking for the classic Fender reverb sounds heard on countless albums over the years will likely view its echo-like tones, modulated artifacts, and limited tweakability as less than authentically Fender. However, more eclectic players who tend to see potential where traditionalists turn up their noses may love the Dewdrop for its vintage pawnshop-prize vibes.

Subdecay Super Spring Theory

The latest from Subdecay’s Newberg, Oregon, shop builds on the company’s discontinued Spring Theory pedal—a two-knob stomp with the stated aim (despite its spring/room mode toggle) of replicating classic blackface reverb. The new Super Spring Theory ups the ante in terms of both ambition and flexibility: It retains the spring/room switch and reverb knob, but replaces the Spring Theory’s depth control with decay, dry, and tone knobs. It also adds a trails toggle that lets you choose whether the reverb shuts off as you disengage the pedal, or decays naturally after you switch it off.At the heart of the Super Spring Theory is a Spin Semiconductor FV-1 programmable DSP chip. Designed by Keith Barr (founder of MXR and Alesis), the FV-1 is used in many current pedals with a more modern take on reverb, including Walrus Audio’s Descent, the EarthQuaker Devices Afterneath, and Mr. Black’s Eterna and SuperMoon pedals.

Considering the FV-1’s wide usage, it’s no surprise the SST offers up nice ambiance—particularly if you’re looking for vast, Strymon-ish room ’verb (minus the fancy shimmer and mod modes) in a more pedalboard-friendly package. Surf Zombie Brook Hoover noted that the room sounds were realistic and “pretty fabulous.” But since we’re focusing on spring sounds here, let’s move on to that.

Ratings

Pros:

Some of the most authentic-sounding spring-reverb tones available in pedal form. Great room sounds. Versatile trails-mode switchability. Can do both trad and rad tones.

Cons:

Internal JFET trimpot (dwell) limits on-the-fly flexibility.

Tones:

Ease of Use:

Build/Design:

Value:

Street:

$179

Subdecay Super Spring Theory

subdecay.com

One interesting departure from most spring-reverb emulators is the SST’s inclusion of two level knobs—one for the reverberated signal, and one for the dry signal—rather than a single mix knob to vary the wet/dry ratio. There’s no dwell knob, either. However, there is an internal trimpot for a JFET boost circuit that controls the signal level sent to the reverb input. Essentially, this is the Super Spring Theory’s dwell control. Subdecay’s Brian Marshall notes that, since the SST’s out-of-the-box spring sound is based on a blackface Fender Twin, the Super comes with the trim set at about 85 percent. If you’re like me, though—a sucker for vast spring ’verb—the SST’s factory setting might feel limiting. You might even dismiss the pedal’s spring sounds as too shallow. But, take the time to open up the pedal and crank the JFET control, and you’ll essentially take the Super to Outboardville—a beautiful place where there’s saltwater in the air and surf tones aplenty. Increasing trimpot gain also boosts the virility of the dry knob, putting a nice, tube-like gain at your disposal in its upper reaches. With the trimpot maxed and dry past 2 o’clock, you get lovely warmth and attitude that goes a long way toward giving the SST the vibe of a tube-driven unit.

Meanwhile, the SST’s most unusual control, decay, not only governs the length of the reverb trails, but is also key to the Spring’s ability to conjure spacier sounds than the other pedals in this roundup—as well as most pedals on the market that focus on spring-style ’verb. Decay functions more akin to a delay’s feedback knob. Past 3 o’clock, it produces psychedelic reverberations that will remind sci-fi fans of Captain Kirk’s phaser on the original Star Trek TV series. This gives the SST a unique spot in the reverb-pedal world, to be sure.

The Verdict

Design-wise, I get why Subdecay didn’t want to clutter the Super Spring Theory’s face with another control. Its four knobs and two mode toggles already offer more flexibility than nearly all similar-sized spring emulators—and the controls are very easy to manipulate mid-gig. But given how much the internal JFET trimpot expands the pedal’s potential, I wish Subdecay had opted for a mini potentiometer or had found another way to let you access all of the pedal’s cool functionality on the fly. If the trim control were on the outside, a test-drive of the SST would have real potential to convert spring enthusiasts who’ve long been waiting for the day when a stomp can elate them as much as an outboard tank (I’m looking at you, surfguitar101 forumites). Certain settings might betray a slightly digital-sounding decay, but optimize the controls to your rig, and the Super really is good enough to please all but the most hardcore of outboard devotees.

On top of all this, the SST gets bonus marks for overall flexibility. Its decay knob allows you to go from traditional to experimental, and the ability to switch trails on or off between songs makes the Super particularly useful for players who want a simple, reasonably sized pedal that can cover both old-school and avant reverb sounds.

Catalinbread Topanga

The guys at Catalinbread’s Portland, Oregon, shop have been trying to stuff little boxes with the elusive tones of yesteryear’s mechanical dinosaurs more than just about any other pedal outfit on the planet in recent days. Their Belle Epoch aims to put revered Echoplex EP-3 tones into a medium-sized stomp, and perhaps most ambitious of all, the Echorec attempted to put the quirky psychedelia of a giant old Binson magnetic-drum delay into an enclosure a fraction of the original’s size.In its pursuit of elusive spring tones, the Topanga uses the same Spin FV-1 chip that drives the Subdecay Super Spring Theory (as well as other pedals that go for more modern sounds). As with the Subdecay, the way the Catalinbread team harnesses that processing power in the Topanga is something special—although the two companies take a different tack in terms of control.

The handsome orange-and-green Topanga approaches the spring-’verb equation simply enough—you get straightforward dwell, tone, and mix controls that react the way you’d expect an outboard unit’s knobs of the same name to behave. Dwell affects the relative depth of the reverb feel, from a muted signal at minimum to a subtle sense of extra body in your sound to a grandness that’ll have you seeing seagulls, swaying palm trees, and beachgoers in vintage swimming attire. Mix takes you from a bold, direct signal at minimum to a nautical washiness that makes your guitar sound like you’re hearing it through a curling wave in suspended animation. With mix cranked, you can even get pretty cool plate-style sounds. And when you dime the tone knob, Topanga sprays your reverberations as brightly as any Chantays cover tune might require, while its minimum setting tames any harshness that a treble-heavy rig might exaggerate.

A fourth knob, volume, controls a discrete preamp that lets you boost your signal to taste. This wonderful addition imparts a very tube-like clean gain that goes a long way toward simulating the warm, vintage vibe of archetypal spring units. I preferred leaving it at noon for a little more oomph and girth—though at maximum it somehow adds a bristling attitude without crossing over into what you’d call proper overdrive.

Ratings

Pros:

One of the most convincing spring-reverb pedals on the market. Wide variety of lush sounds—from subtle to surf-able. Volume (gain) knob adds tube-like warmth, dimension, and attitude.

Cons:

Hidden modulation mode needs separate on/off switch.

Tones:

Ease of Use:

Build/Design:

Value:

Street:

$195

Catalinbread Topanga

catalinbread.com

Virtually my only complaint about the Topanga is its hidden modulation mode—which I discovered by accident. I dial my rig to run a pretty trebly sound—for maximum snap and twang—so I preferred setting the Topanga’s tone knob at minimum to keep reverberations from sounding harsh. The second time I powered up the pedal, I couldn’t figure out why there was an odd shimmer in the decays. The pedal didn’t come with documentation about this, nor did catalinbread.com cover it, but I eventually found mentions of Topanga’s hidden mod mode—which is activated by applying power with the tone knob at minimum—on various forums. To me, the modern feel of mod mode is a bit antithetical to the notion of capturing authentic 1960s spring reverb, but to some it’s sure to be viewed as bonus flexibility. I just wish you could deactivate it with a toggle or an internal DIP switch.

The Verdict

The most militant spring-reverb adherents may never be satisfied with any “spring reverb” that isn’t, in fact, a spring reverb—and good on them for sticking to their guns. I’ll admit that A/B-ing the Catalinbread Topanga with a ’63 Fender Reverb revealed detectable differences in sound—particularly if you’re looking for the same tones at the same knob settings. That said, the differences can be difficult to quantify.

When Surf Zombie Brook Hoover plugged in, he started nodding in appreciation almost immediately. “It sounds like early-’60s Fender—you can hear the splash of the springs. It makes you wanna dig in and have fun. It doesn’t make you think, ‘Oh, this is digital.” He added, “Other units get less believable with higher dwell settings, but this is believable even with it maxed.”

Like the Subdecay, certain Topanga settings that don’t complement your rig’s overall sound might reveal an ever-so-slight hint of digital-ness. And there’s perhaps a greater dimensionality from the Fender when you’re sitting there staring at your amp, scrutinizing the minutest of nuances. But I would love to twiddle the knobs during an A/B blindfold test with stalwart spring freaks. Dialed right, the Topanga (like the Super Spring Theory) can come so close to authentic spring sounds that when you’re A/B-ing you start to wonder if the differences you’re hearing aren’t simply attributable to the fact that you see your hands swapping cables from pedal to tank.