“The Ballad of John Henry” looms large in the annals of American folklore. Versions of it have appeared in a number of narratives, usually referring to Henry as a “steel-driving” man who dies from the effort of defeating a steam drill machine designed to replace his ilk. Henry, who cuts holes in stone for dynamite with his hammer and chisel or alternately pounds railroad spikes, represents a way of life threatened by a powered machine.

In this clash between man and rising technology we are reminded that the fear of progress is an age-old battle that humans have fought with every advance in tools. So goes the advent of computer numeric controlled machines. Commonly referred to as CNC, these machines can be routers, saws, welders, or any number of robotic machines programmed to do heavy, repetitive work—the kind that killed John Henry.

At first, these machines were so huge and expensive that only large companies could afford them. The software alone could run into five-figure sums, locking out even medium-size operations. In recent years however, the cost of smaller machines has dropped to the point where even hobbyist builders can afford to put one in their garage or basement shop. Yet in the minds of many guitarists, the purity of a handbuilt instrument elevates it to a higher standard. But what is really the difference?

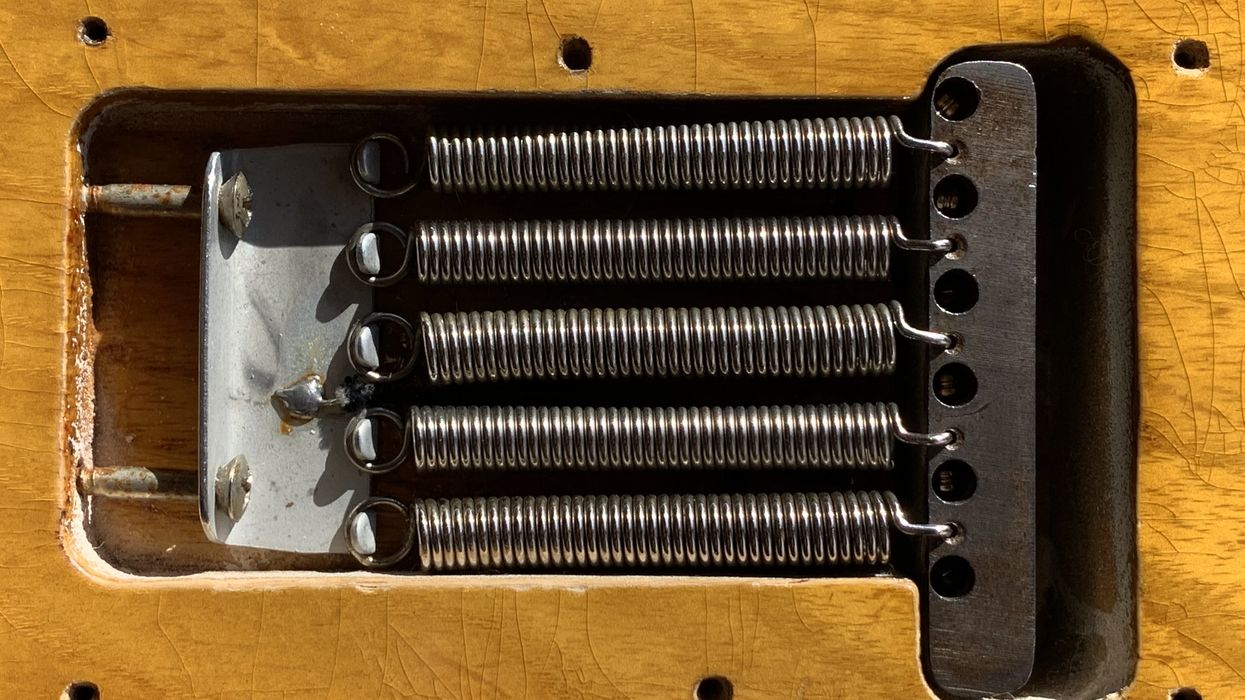

A century ago, guitars were made primarily with hand tools. But by the 1940s, guitar factories used large cutting machines, like shapers and routers, to perform the basic forming of bodies and necks. A staple of the guitar-building trade was the overarm “pin” router. Along with its cousin the profile shaper, it simplified and accelerated the manufacture of instruments. The pin router is extremely flexible and can be used for hundreds of woodworking tasks. The tooling used to create repeatable parts can actually be made by the machine itself by copying an original form, such as an existing guitar body or pickguard.

Other advances in guitar manufacturing have included specialized machinery that followed physical templates to carve necks or create the archtops on bodies. Gibson famously used both these machines, which were originally conceived to make gunstocks and chair seats, respectively. Guitar factories employed multi-head drill presses to drill six tuner holes simultaneously, and mechanized glue spreaders replaced brushes and bottles. Each of these changes increased output and reduced the amount of hand skills required to make a profit. It also ushered in a new level of standardization that reduced human error. Today, a single CNC machine can do all of the above and more.

“Guitar factories employed multi-head drill presses to drill six tuner holes simultaneously, and mechanized glue spreaders replaced brushes and bottles.”

Just the same, there has always been a subset of guitar makers that rely mostly on hand tools. I find it to be the most satisfying part of what I do. For decades, small builders have existed alongside the behemoths as a way of providing the short run or custom work that a large factory couldn’t afford or be bothered to do. The rising success of small builders who focused on handwork paved the way for large companies to create their own in-house custom departments. Now, the versatility, lower cost, and smaller footprint of CNC milling machines allows both types of shops to do a variety of modifications easily and profitably. So, what does this mean for the customer? Do robot machines suck the soul out of an instrument?

The way I look at it, there is a similarity between all means of manufacture. In the case of the shaper and pin-router era, designs had to be drawn by pen and paper, then transferred using hand tools into physical templates. At that point, an operator loaded a wooden blank onto a fixture and muscled it against a spinning cutter along a path determined solely by the template. The creativity and craftsmanship ended before the wood ever saw the blade, and the operator was mostly muscle. In CNC manufacturing, the designer’s pen and paper is replaced by the mouse and computer screen. The nuance of the procedures are determined in the design and tool-path phase long before someone on the shop floor loads the blank and pushes the start button.

The truth is that every instrument is made using some kind of tool, and automated equipment only does a small part of the job. A seasoned builder can spot problems (and opportunities) before they occur, which machines can’t do yet. There is still a huge amount of handwork required to turn a CNC creation into a guitar. If you think that wood, plastic, and steel goes in one end of the machine and a finished instrument comes out of the other, you haven’t been paying attention. It’s just that now electric motors are the muscle instead of John Henry.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)