Henry Juszkiewicz, CEO of Gibson, was recently quoted in the press blaming some of his company’s financial woes on his dealer network. Bad move. You’ve got to know which side your bread is buttered on. Even so, he has a valid point. The claim that many guitar stores don’t provide a superior customer experience is often the case. In my estimation, successful retailers understand this and have created welcoming atmospheres in their shops. Meanwhile, there is a bigger picture and forces so vast that the arc of any given endeavor is hard to blame on a single thing.

It’s easy to be cavalier when everyone wants your product, a condition the major guitar companies have enjoyed for decades. But sometimes companies get caught outside the fashion trend looking in. The mid 1980s was one such time. I lived through that period and can tell you it wasn’t much fun being a vintage-style builder in a world swathed in spandex. If you didn’t slap a locking trem and zebra stripes on your product, you were doomed.

Luckily, things got back to real by the time the grungy ’90s rolled around. (Thank goodness for Doc Martens, plaid, and Slash.) It was just about this time that another generation of guitarists discovered vintage guitars as superior instruments, driving prices higher.

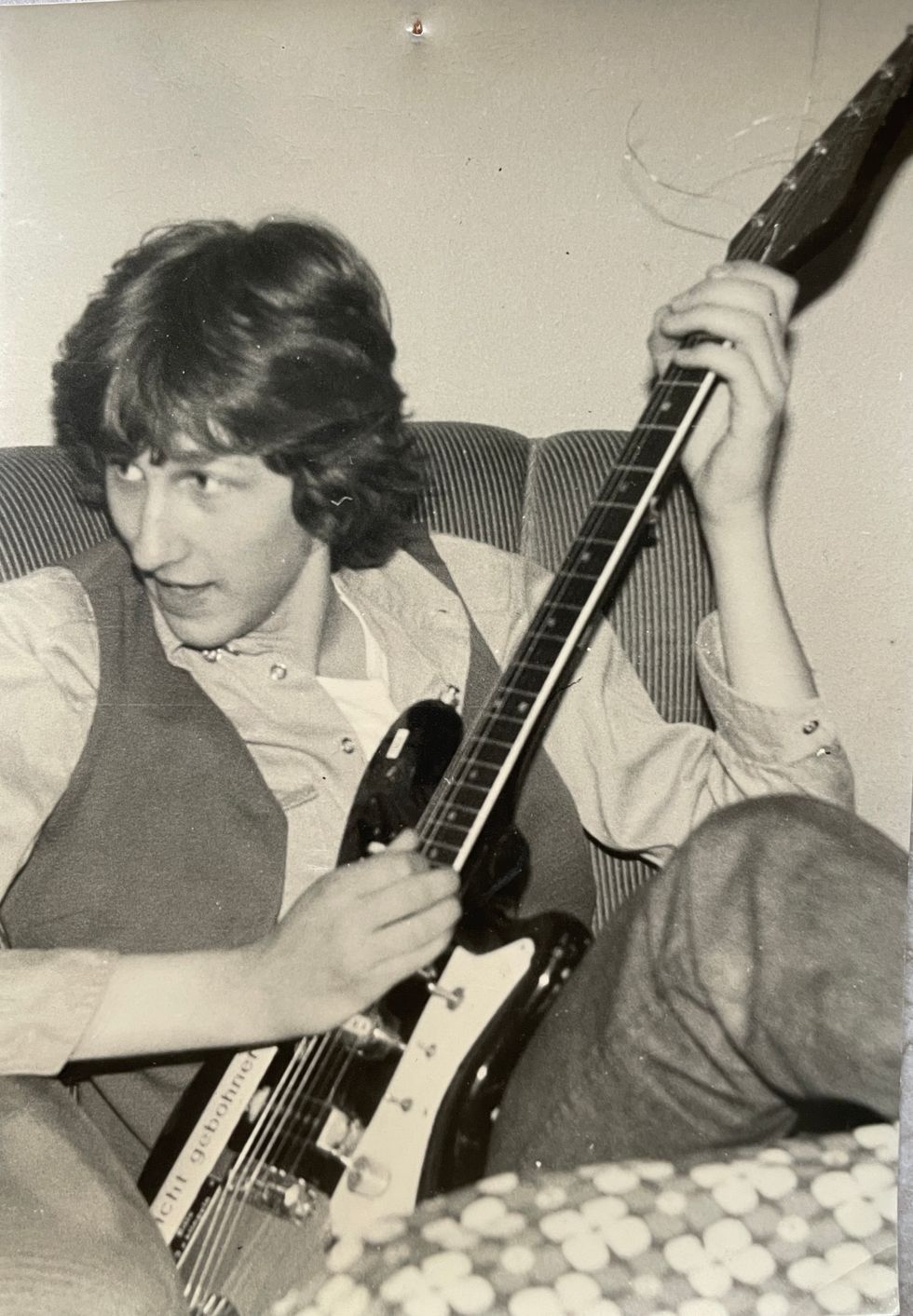

A look back in time reveals an obvious pattern. In any time period or genre, players began their careers using cheap instruments. When you don’t have the do-re-mi, you beg, borrow, steal, or buy what you can. From Elmore James and Buddy Guy to the Beatles, they all ditched the student models and got expensive guitars as soon as they had a little money. Even the well-to-do suburban rockers of the 1960s followed this format. Mom and dad weren’t shelling out beaucoup bucks for an expensive major-league electric guitar until they knew it wasn’t just a passing fancy. The Silvertone or Supro from the Sears catalog would just have to do.

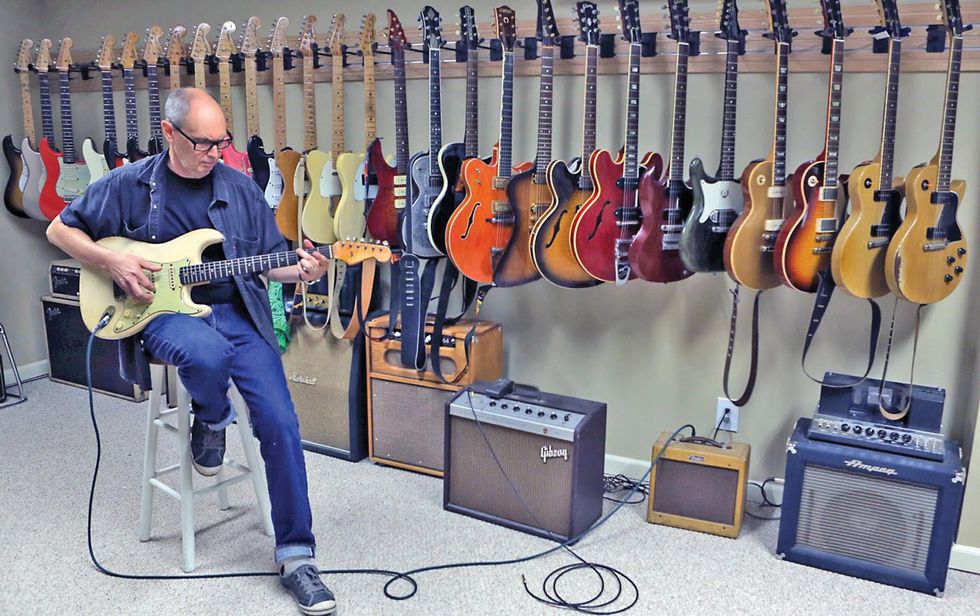

This is about the only thing the garage bands of the Beatles era shared with Maxwell Street. The players who kept at it saved for a Strat or a Rickenbacker and traded up for a Fender Showman amp. Bukka White got his National steel and Buddy Guy and Hubert Sumlin moved up to Gibsons. It all comes down to money. What’s amusing is that the fashion of today is the castoffs of yesteryear. Guitarists with expensive pedal and amp rigs tramp onstage with faux-pawnshop planks or modern recreations of such in search of “authenticity.” I think they took away the wrong part of the Jack White lesson.

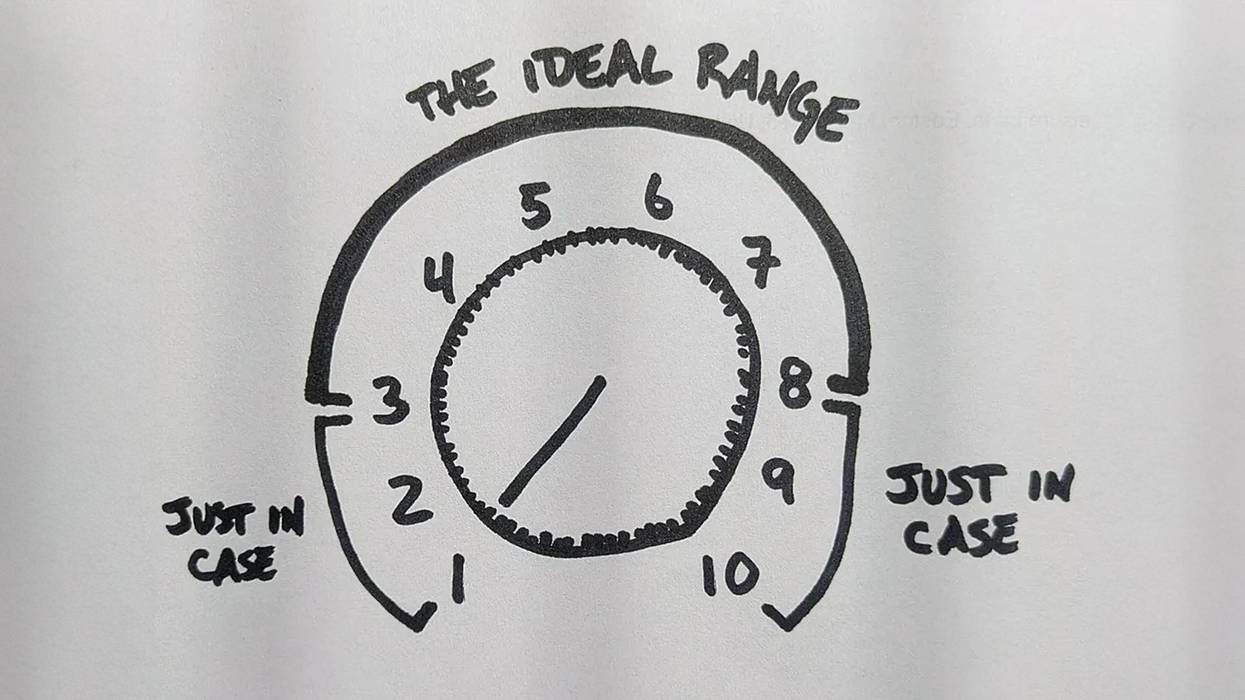

Before you pile on me about how these once-inexpensive beginner guitars have soul and voice, refer to my earlier essays on the glory of gold-foil pickups or how every guitar has a useful purpose. It’s just the mad rush to appear alt by brandishing a cheapo axe that I question. The corporate vision of Gibson as a “lifestyle brand” and Fender’s insistence of slathering their logo on everything from earbuds to baby onesies has tipped the scales. I can respect the idea of monetizing brand identity—everyone needs to put food on the table—but this blatant commoditization of the musical tool ruins it for me. Every generation seeks to throw off the shackles of the past and push into territory that honors tradition while blending those influences into something timely. It’s just a shame that great instruments (or their builders) are stigmatized for the fashion of affordability. I don’t call for the downfall of Bentley or Ferrari just because I can’t afford their products, and I don’t convince myself that my affordable car is better.

On the upside, some truly interesting designs have emerged under the guise of being against the grain. It has opened the eyes of some of the most dyed-in-the-wool traditionalists, and forced them to consider the off-brands. The proliferation of small builders with “oddball” esthetics symbolizes more than just the marketplace speaking. The sheer number of choices represents a large proportion of the thousand paper cuts it takes to kill a legacy brand. Still, I wouldn’t count the old guard out just yet. All the major brands have endured downturns in fortune. From the mid 1970s to the ’80s, Gibson’s quality was not impressive and the company’s viability was dubious due to sustained losses incurred by mismanagement. Fender was on the brink around the same time for similar reasons. For those who point to high prices as the culprit, I suggest you examine the balance sheet of any manufacturing company trying to survive in America. It’s hard to kill off a legacy brand, but if it actually happens, we’ll all be losers.