Writing the arrangement, hiring and leading the band, and making the artists and network feel at ease was a challenge, but all of that was easy compared to the daunting task of playing Paul Franklin's pedal steel parts in a live, televised awards show. Paul Franklin is the pedal steel equivalent of Andrés Segovia, Jimi Hendrix, Jaco Pastorius … take your pick. He's taken the instrument to heights never before imagined. Me filling Paul Franklin's shoes is like Woody Allen stepping in for Mike Tyson.

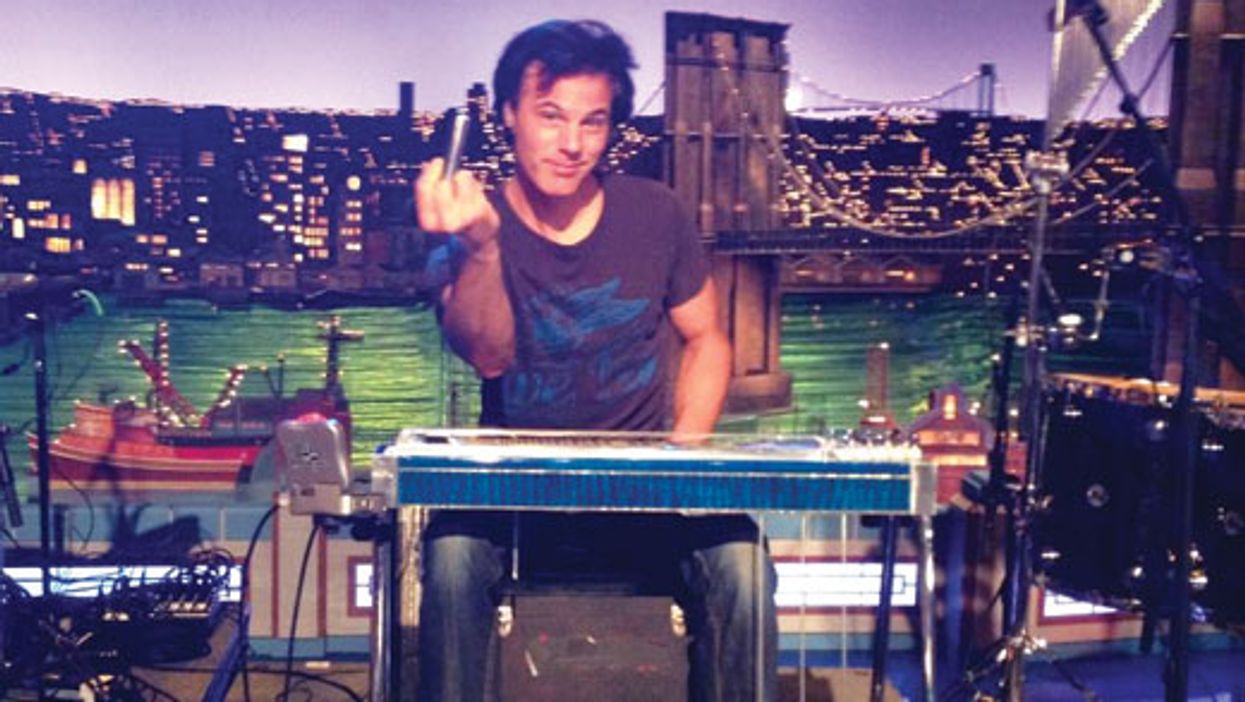

So why didn't I just play guitar and hire a killer steel player? Because TV likes young, fresh faces. No offense intended toward my fellow E9ers, but most pedal-steel players look about as youthful as Jed Clampett—probably because it takes a lot of years before you can make something that resembles music on that baffling instrument. Luckily, with the right lighting, some stage smoke, and hair dye, I can still fool an audience into thinking I'm youthful-ish, so the pedal steel slot fell to me.

I worked on the steel parts until they sounded solid, but there were a few spots that I was bluffing my way through. I wanted to raise the bar because this was a huge performance with nearly everybody in the industry sitting in the audience while millions watched on TV. It was time to call my sensei.

My pedal-steel sensei is Dave Ristrim. Dave is widely talented. When it comes to figuring out music, he works like an archeologist. Dave sifts through the densest tracks, going layer by layer, picking up each note with a tiny pair of delicate tweezers and dusting it off with a camel hairbrush, and discovering three different inversions for every passage. Dave has big ears. I do not.

I sent Dave an MP3 of the most troubling section of the arrangement, and by the time I arrived at his house, he had written the tab. I set up my steel across from him, and Dave played Franklin's part as easily as Kobe Bryant makes an unguarded layup.

Then came the embarrassing part. Arenas and TV performances don't shake me up, but sitting across from somebody as talented as Dave makes me painfully aware of my many flaws. Dave played the first part slowly while explaining how Franklin probably did it. I repeated what I thought he played, and he said, “No, you're pressing your A and B pedals too late. Listen to this."

Dave played it again, and I thought I copied him exactly.

“Nope, you're still late. Listen to how I play it."

Dave played it again, but it was like listening to a dog whistle. I could not hear the difference, which pretty well illustrates that the difference between a good performance and a great performance comes down to nuance.

Dave, showing incredible patience and generosity, kept going slowly line-by-line until this simple lesson turned into an eight-part BBC series with subcategories of increasing complexity. About two hours in I felt like Homer Simpson—blank eyes staring forward as Steamboat Willie danced about my brain. I dreamt of being far away, not thinking, perhaps eating pasta and watching TV. My brain was full so I tapped out, drove home, and passed out on my couch. After I woke I played through the part about 20 times and then packed up for the next day's rehearsal.

I tried to incorporate Dave's teachings at that rehearsal, but it sounded like I was playing with my toes instead of my fingers. After playing the arrangement a few times, I admitted defeat and reverted to my tried and true bad habits, downgrading to my solid though not stellar part.

The next day at the taping, I ran into Ristrim, who was also playing the show with Luke Bryan. I gave Dave a deep penitent bow, hung my head in shame, and said, “Sensei, I can't get that part right so I'm reverting back to my old, easier part."

Dave said, “Yeah man, of course. You don't want to go into unfamiliar territory like that on TV. Your part's cool. Don't sweat it. Let's hang again at my place when we both get off tour and I'll show you what I'm doing."

I felt what could only be described as love, gratitude, and relief. Dave's bit of encouragement made me confident about the performance that night, and I knew that, in the big picture, those bits that were driving me crazy would eventually get better with some practice and the help of my friend.

The world can be a lonely, scary place where we waste a lot of energy worrying about catastrophes that never happen. Find a sensei that can give you a little guidance and the trip is infinitely more pleasant. Then pay it back, or forward, by helping somebody a few steps behind you.

Dennis Cagle, Reader

Dennis Cagle, Reader