Good orchestras never have a bad mix. From any seat in the house, stage to balcony back row, everyone hears every note from the lean-in-close pp to the rip-your-head-off ff. It's not so much that orchestral instruments naturally blend together, though most do. It's more that the players know how to control their volume to make them blend, and then the conductor adds and subtracts as needed.

Similarly, good jazz bands usually have a good stage mix. Barring the perfect storm of a horrible venue combined with an idiot engineer, good jazzers will hunker in close, listen intently, and manage their volume organically. They sound great because good jazzers are like the best conversationalists: They listen when somebody else has the floor, then reply when it's their turn. They listen well because they have to listen to know where the song is going.

If you come from the classical or jazz world, you'd think hearing yourself while playing with others shouldn't be a problem, but if you play with loud drums in small spaces, you've probably had more bad-sounding stages than good ones. Why is a stage mix such a crapshoot?

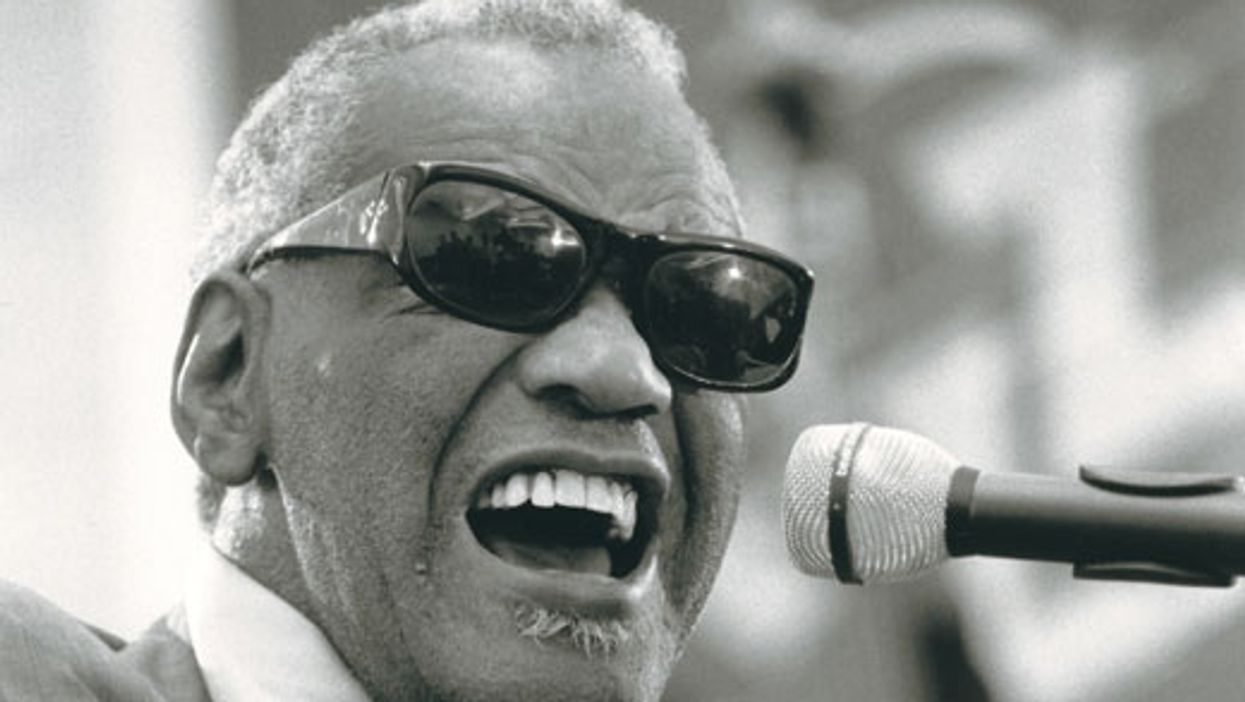

My buddy, advisor, and engineer of choice, Wayne Pauley, used to mix Ray Charles. Wayne told me that Ray did not allow stage monitors. Ray mixed by place and space. He'd locate warm instruments, like the bass, close to him and loud stuff, like drums and horns, further back. Ray would hear his voice as it came out of his mouth and via the front-of-house mix. The stage mix came down to the musicians listening and finding their blend. Wayne's job was making the sound on the stage hit the audience the same way, with the vocal lying over the top.

After Ray Charles, Wayne was mixing pop act Nikka Costa when she opened for Prince. At that time, Prince had one engineer who handled the front of house and the stage monitors. Because the Royal Purple One had played and/or composed all of the parts in the original studio versions of his songs, he felt that everybody, be it the band or audience, should hear what he heard. There was one mix.

Prince wanted all of the players to control their dynamics by responding to what was going on in the songs instead of focusing too heavily on what they were playing. In short, Prince made sure that the overall performance and sound trumped any one player's personal performance.

It took me a long time to make friends with monitors. I spent most of my formative years playing with loud bands in tiny venues. There's no way to make that work unless there's a mutual disarmament pact where everybody turns down, which rarely happens because:

• Most drummers like to beat shit as hard as they can all the time.

• Bass is so omnidirectional that the bass amp will be roughly as loud to the people around it as it is to the bass player standing right in front of it. Bassists may think they're at a reasonable level when they are the loudest musicians onstage.

When I began playing in situations with actual working monitors and the space to hear them, it took me a long time to get over the old mentality of just trying to hear myself over the noise onstage.

A breakthrough came when I took the Ray Charles/Prince approach while playing in Lee Brice's band. It was a scary leap of faith because I often play pedal steel or slide on tour, and I'm paranoid about hearing my pitch. But eventually I set my volume just slightly over the volume of the keys. I found that when our keyboardist, Reggie Bradley Smith, hit his B3 at full volume, I could barely hear my steel when I was playing the right part to support Reg—but if I got out of tune I could hear the bad notes clearly. It's like magic: Out of tune stuff cuts through a mix while in-tune blends right in. Same with meter: If you're in, you blend; if you're out, it's obvious. In short, I began experiencing live music less as my own performance and began feeling the whole band experience. I also found that I played less, which enabled more important parts to cut.

I made the same adjustment in the studio. Before, I wanted “more me," but I found that I grooved better and listened more attentively when I heard everyone else clearly.

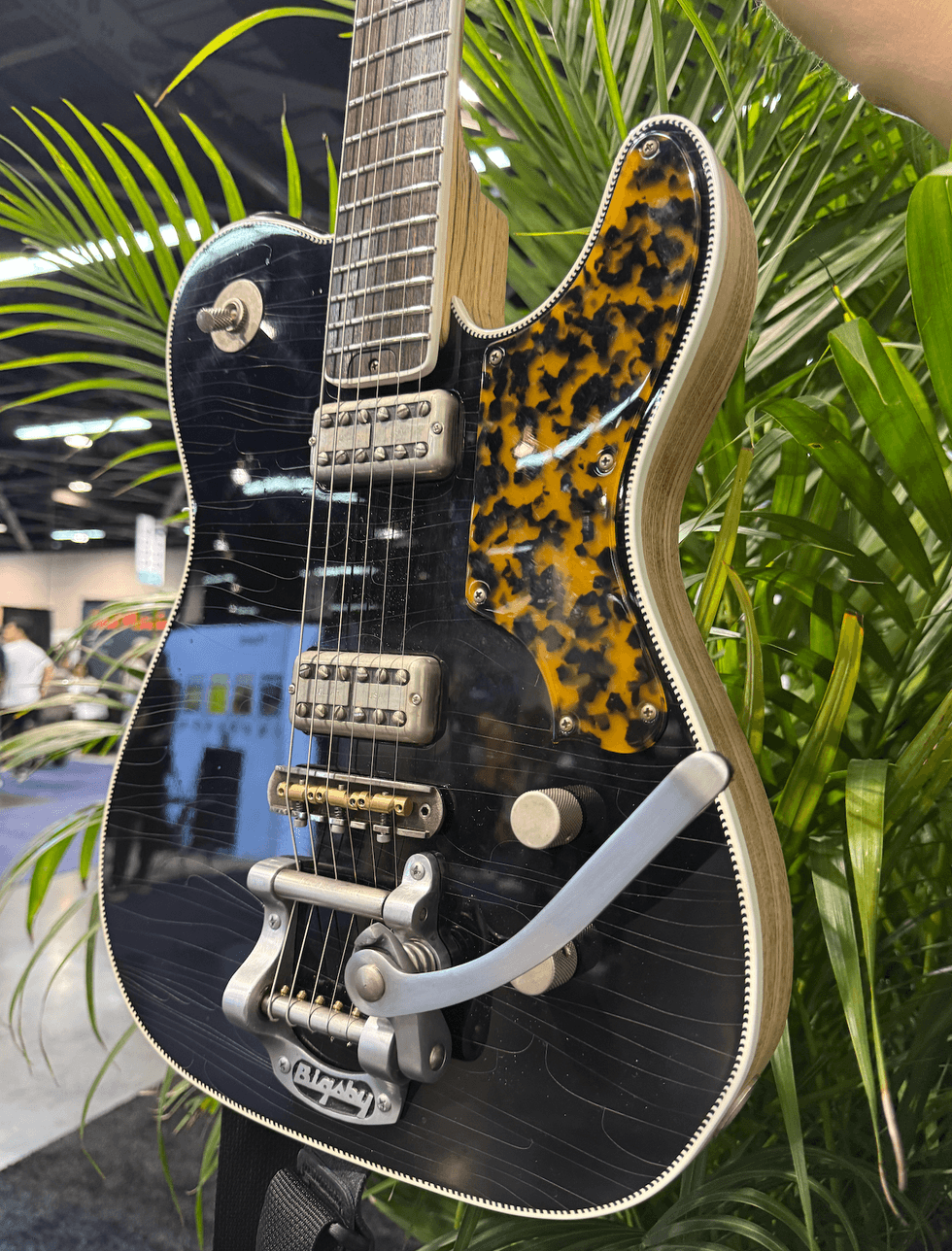

A 2010 Premier Guitar article about Jimmy Herring showed a stage set-up that included an individual volume pedal for each band member. Sounds like a wiring nightmare, but that emphasizes how important it is to hear everybody.

Music sounds best when everybody is working toward enhancing the overall sound rather than their own performances. If you can get your band thinking about the greater good, you will all sound better. Good luck with that loud drummer.

Dennis Cagle, Reader

Dennis Cagle, Reader