Don't even ask me how I found out about this, but on a recent night while stumbling around the internet in a whiskey haze, I discovered an auction for some of Kurt Cobain's hair. Yes, six glorious strands of bleached hair were neatly encased in plastic and accompanied with all sorts of provenance to assure any bidder that this was the real deal. Of course, I immediately set to thinking about the economic ramifications of placing a bid (starting at $2,500), and after a few drinks I was set to put in a last second snipe. Alas, I fell asleep and quickly forgot about it. When I checked back a few days later I saw the final price was … $13,800!

Heck, I saw Nirvana live several times back in the day and I sure wasn't thinking about Kurt's hair. But I was always impressed by how such a small guy could have such a powerful presence. I also marveled at his choice of gear, which always seemed sort of random. I mean, Kurt would switch out all manner of Fender guitars, but then there were always these oddballs that he would use. Among his early favorites were Univox Hi-Fliers, which I really liked, because one of my early favorites was also a Hi-Flier.

There are all sorts of great players who've swung these around on stage, including Lee Renaldo and Dexter X, but it was Kurt and his Hi-Flier that really resonated with my young self.

Back in the late 1980s, I saw Nirvana for the first time in Hoboken, New Jersey. The night was mostly fuzzy, but Kurt playing a Hi-Flier really blew me away. Like, here I was … some goofball kid who was obsessed with cheap, weird guitars, and then there's this little powerhouse of a guy playing really heavy riffs on a pawnshop guitar. It was a life-changing moment. I felt validated by seeing another guitar player with one of my bargain-shelf favorites.

In 1968, the Westbury, New York–based Unicord Corporation was importing some very interesting Japanese gear, which was rather amazing and affordable. My original, longtime setup consisted of a Hi-Flier and a Univox Super-Fuzz, both going through an old Harmony 420 bass amp. Each component in that chain was more than I probably deserved as a player (I was always more of a noisemaker), 'cause all the Univox guitars from the late '60s and early '70s were consistent, sounded fine, and could pretty much hold tuning.

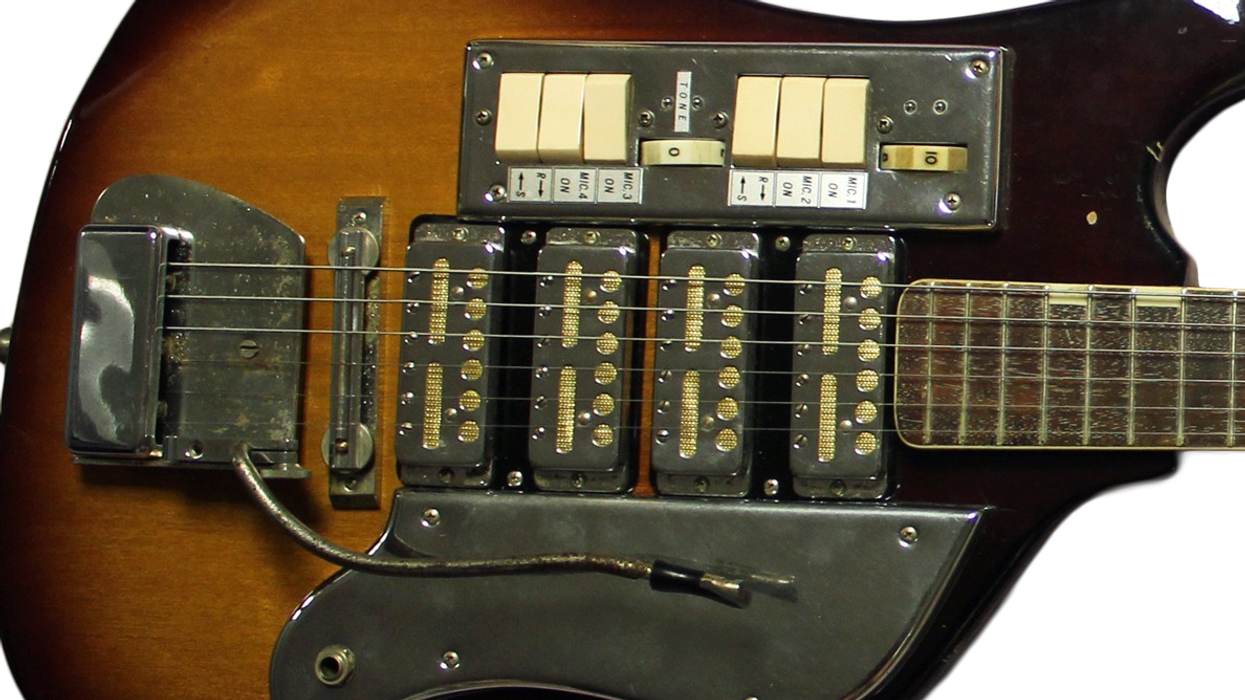

Simple but effective, this 1971 Univox has just one control each for tone and volume, hot single-coil pickups, and a Jazzmaster-like vibrato bridge that holds tune far better than most budget imports of its day.

Univox guitars were built in the Matsumoku facility in Matsumoto City, Japan, in a former Singer Sewing Machine factory which was repurposed in the mid-1960s to make some of the country's better electric guitars for about 20 years. Univox-branded guitars were really common on the secondhand market of the 1980s and could be had for a song. Heck, even the list price on a Hi-Flier was only around $90 in the early '70s. (Today, old Hi-Fliers tilt up to a grand!) That was really the dawn of the copy era, so, to outdo the American competition, Univox products were priced much lower and had much cooler names. Les Paul copies were called the Gimme and the Mother, their 335 knock-off was the Coily, and the Dan Armstrong plexiglas copy was dubbed Lucy. I really need to write a book on weird guitar names, and I really need to honor the hype-writer of the day who described the Hi-Flier 6-string and bass as:

Lets ya feel free … with curves where ya want 'em. Loose … Flat … Light. A guitar to fly with, slide with, bend with, and a bass that gets funky!

Yo, dig that! Throughout the 1970s, the Hi-Flier went through a few changes, such as a switch to humbuckers, but the general layout and feel stayed true to its Mosrite roots and it was quite the player—with one volume and one tone control, and a 3-way pickup switch. And yes, the pickups on my '71 are single-coils, but they're way overwound and read hot, at about 9k. These P-90 look-alikes just scream and are always on the edge of exploding when some fuzz or distortion is added. The neck profile on Matsumoku-made guitars tends to be a bit flat in the shoulder, à la early Epiphone/Gibson electrics, but these Hi-Fliers are thinner across the nut. As for the vibrato, it has a really tight, Jazzmaster feel. Japanese twang-bar bridges are not usually that great, but this unit was one of the first good ones.

I don't think you could go wrong with any Hi-Flier version, although there are people who swear by one model or another. There are all sorts of great players who've swung these around on stage, including Lee Renaldo and Dexter X (Man or Astroman?), but it was Kurt and his Hi-Flier that really resonated with my young self. Oh, and if any of you have any of Kurt's hair, give me a call, dig?

Univox Hi Flier Phase II Guitar Demo

Mike Dugan demos a 1971 Univox Hi-Flier, showing that it can chime, turn dirty, and produce surf-style vibrato tones with the best of Japan's '60s and '70s pawn shop prizes. And yeah, there's congas and "Jingo!"

Then, in the dream, I “awoke” and realized I was back in my bedroom, and it was all just a dream. The kicker is that I was still dreaming, because that “paddle” guitar was suddenly in my hands—then I woke up for real! How about that misadventure?

Then, in the dream, I “awoke” and realized I was back in my bedroom, and it was all just a dream. The kicker is that I was still dreaming, because that “paddle” guitar was suddenly in my hands—then I woke up for real! How about that misadventure?![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)